Chapter III

Scientific Technique in an Oligarchy

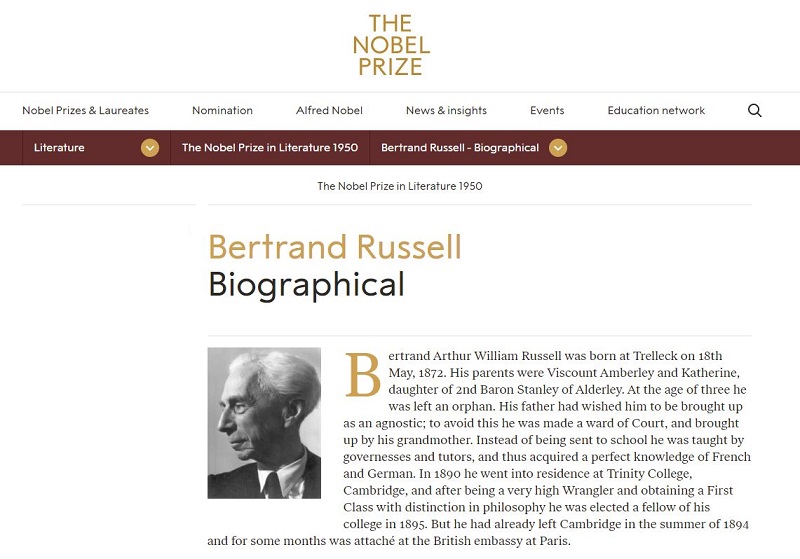

By Bertrand Russell, Tim Sluckin

The Impact of Science on Society

“I do not believe that dictatorship is a lasting form of scientific society

— unless (but this proviso is important) it can become world-wide.”

ABSTRACT

A new kind of oligarchy was introduced by the Puritans during the English Civil War. They called it the ‘Rule of the Saints’. A scientific oligarchy, accordingly, is bound to become what is called ‘totalitarian’, that is to say, all important forms of power will become a monopoly of the State. Oligarchies, throughout past history, have always thought more of their own advantage than of that of the rest of the community. The completeness of the resulting control over opinion depends in various ways upon scientific technique. Scientific societies are as yet in their infancy. A totalitarian government with a scientific bent might do things that to us would seem horrifying. The government, as opposed to its individual members, is not sentient; it does not rejoice at a victory or suffer at a defeat. A system may be more oligarchic or less so, according to the percentage of the population that is excluded; absolute monarchy is the extreme of oligarchy.

CHAPTER III

Scientific Technique in an Oligarchy

I mean by “oligarchy” any system in which ultimate power is confined to a section of the community: the rich to the exclusion of the poor, Protestants to the exclusion of Catholics, aristocrats to the exclusion of plebeians, white men to the exclusion of colored men, males to the exclusion of females, or members of one political party to the exclusion of the rest. A system may be more oligarchic or less so, according to the percentage of the population that is excluded; absolute monarchy is the extreme of oligarchy. Apart from masculine domination, which was universal until the present century, oligarchies in the past were usually based upon birth or wealth or race. A new kind of oligarchy was introduced by the Puritans during the English Civil War. They called it the “Rule of the Saints.” It consisted essentially of confining the possession of arms to the adherents of one political creed, who were thus enabled to control the government in spite of being a minority without any traditional claim to power. This system, although in England it ended with the Restoration, was revived in Russia in 191 8, in Italy in 1922, and in Germany in 1933. It is now the only vital form of oligarchy, and it is therefore the form that I shall specially consider.

We have seen that scientific technique increases the importance of organizations, and therefore the extent to which authority impinges upon the life of the individual. It follows that a scientific oligarchy has more power than any oligarchy could have in pre-scientific times. There is a tendency, which is inevitable unless consciously combated, for organizations to coalesce, and so to increase in size, until, ultimately, almost all become merged in the State. A scientific oligarchy, accordingly, is bound to become what is called “totalitarian,” that is to say, all important forms of power will become a monopoly of the State. This monolithic system has sufficient merits to be attractive to many people, but to my mind its demerits are far greater than its merits. For some reason which I have failed to understand, many people like the system when it is Russian but disliked the very same system when it was German. I am compelled to think that this is due to the power of labels; these people like whatever is labeled “Left” without examining whether the label has any justification.

“(We) are the wise and good; we know what reforms the world needs; if we have power, we shall create a paradise.” And so, narcissistically hypnotized by contemplation of their own wisdom and goodness, they proceeded to create a new tyranny, more drastic than any previously known. It is the effect of science in such a system that I wish to consider in this chapter.”

Oligarchies, throughout past history, have always thought more of their own advantage than of that of the rest of the community. It would be foolish to be morally indignant with them on this account; human nature, in the main and in the mass, is egoistic, and in most circumstances a fair dose of egoism is necessary for survival. It was revolt against the selfishness of past political oligarchies that produced the Liberal movement in favor of democracy, and it was revolt against economic oligarchies that produced socialism. But although everybody who was in any degree progressive recognized the evils of oligarchy throughout the past history of mankind, many progressives were taken in by an argument for a new kind of oligarchy. “We, the progressives” — so runs the argument — “are the wise and good; we know what reforms the world needs; if we have power, we shall create a paradise.” And so, narcissistically hypnotized by contemplation of their own wisdom and goodness, they proceeded to create a new tyranny, more drastic than any previously known. It is the effect of science in such a system that I wish to consider in this chapter.

“whoever questions the governmental dogma questions the moral authority of the government, and is therefore a rebel.”

In the first place, since the new oligarchs are the adherents of a certain creed, and base their claim to exclusive power upon the Tightness of this creed, their system depends essentially upon dogma: whoever questions the governmental dogma questions the moral authority of the government, and is therefore a rebel. While the oligarchy is still new, there are sure to be other creeds, held with equal conviction, which would seize the government if they could. Such rival creeds must be suppressed by force, since the principle of majority rule has been abandoned. It follows that there cannot be freedom of the press, freedom of discussion, or freedom of book publication. There must be an organ of government whose duty it is to pronounce as to what is orthodox, and to punish heresy. The history of the Inquisition shows what such an organ of government must inevitably become. In the normal pursuit of power, it will seek out more and more subtle heresies. The Church, as soon as it acquired political power, developed incredible refinements of dogma, and persecuted what to us appear microscopic deviations from the official creed. Exactly the same sort of thing happens in the modern States that confine political power to supporters of a certain doctrine.

The completeness of the resulting control over opinion depends in various ways upon scientific technique. Where all children go to school, and all schools are controlled by the government, the authorities can close the minds of the young to everything contrary to official orthodoxy. Printing is impossible without paper, and all paper belongs to the State. Broadcasting and the cinema are equally public monopolies. The only remaining possibility of unauthorized propaganda is by secret whispers from one individual to another. But this, in turn, is rendered appallingly dangerous by improvements in the art of spying. Children at school are taught that it is their duty to denounce their parents if they allow themselves subversive utterances in the bosom of the family. No one can be sure that a man who seems to be his dearest friend will not denounce him to the police; the man may himself have been in some trouble, and may know that if he is not efficient as a spy his wife and children will suffer. All this is not imaginary; it is daily and hourly reality. Nor, given oligarchy, is there the slightest reason to expect anything else.

People still shudder at the enormities of men like Caligula and Nero, but their misdeeds fade into insignificance beside those of modern tyrants. Except among the upper classes in Rome, daily life was much as usual even under the worst emperors. Caligula wished his enemies had but a single head; how he would have envied Hitler the scientific lethal chambers of Auschwitz! Nero did his best to establish a spy system which would smell out traitors, but a conspiracy defeated him in the end. If he had been defended by the N.K.V.D. he might have died in his bed at a ripe old age. These are a few of the blessings that science has bestowed on tyrants.

Consider next the economic system appropriate to an oligarchy. We in England had such a system in the early nineteenth century; how abominable it was, you can read in the Hammonds’ books. It came to an end, chiefly owing to the quarrel between landowners and industrialists. Landowners befriended the wage-earners in towns, and industrialists befriended those in the country. Between the two, factory Acts were passed and the Corn Laws were repealed. In the end we adopted democracy, which made a modicum of economic justice unavoidable.

In Russia the development has been different. The government fell into the hands of the self-professed champions of the proletariat, who, as a result of civil war, were able to establish a military dictatorship. Gradually irresponsible power produced its usual effect. Those who commanded the army and the police saw no occasion for economic justice; soldiers were sent to take grain by force from starving peasants, who died by millions as a result. Wage-earners, deprived of the right to strike, and without the possibility of electing representatives to plead their cause, were kept down to bare subsistence level. The percentage difference between the pay of army officers and that of privates is vastly greater in Russia than in any Western country. Men who hold important positions in business live in luxury; the ordinary employee suffers as much as in England one hundred and fifty years ago. But even he is still among the more fortunate.

Underneath the system of so-called “free” labor there is another: the system of forced labor and concentration camps. The life of the victims of this system is unspeakable. The hours are unbearably long, the food only just enough to keep the laborers alive for a year or so, the clothing in an arctic winter so scanty that it would barely suffice in an English summer. Men and women are seized in their homes in the middle of the night; there is no trial, and often no charge is formulated; they disappear, and inquiries by their families remain unanswered; after a year or two in Northeast Siberia or on the shores of the White Sea, they die of cold, overwork, and undernourishment. But that causes no concern to the authorities; there are plenty more to come.

This terrible system is rapidly growing. The number of people condemned to forced labor is a matter of conjecture; some say that 16 per cent of the adult males in the U.S.S.R. are involved, and all competent authorities (except the Soviet Government and its friends) are agreed that it is at least 8 per cent. The proportion of women and children, though large, is much less than that of adult males.

Inevitably, forced labor, because it is economical, is favorably viewed by the authorities, and tends, by its competition, to depress the condition of “free” laborers. In the nature of things, unless the system is swept away, it must grow until no one is outside it except the army, the police, and government officials.

From the standpoint of the national economy, the system has great advantages. It has made possible the construction of the Baltic-White Sea canal and the sale of timber in exchange for machinery. It has increased the surplus of labor available for war production. By the terror that it inspires it has diminished disaffection. But these are small matters compared to what — we are told — is to be accomplished in the near future. Atomic energy is to be employed (so at least it is said) to divert the waters of the River Yenisei, which now flow fruitlessly into the Arctic, so as to cause them to bestow fertility on a vast desert region in Central Asia.

But if, when this work is completed, Russia is still subject to a small despotic aristocracy, there is no reason to expect that the masses will be allowed to benefit. It will be found that radioactive spray can be used to melt the Polar ice, or that a range of mountains in northern Siberia would divert the cold north winds, and could be constructed at a cost in human misery which would not be thought excessive. And whenever other ways of disposing of the surplus fail, there is always war. So long as the rulers are comfortable, what reason have they to improve the lot of their serfs?

I think the evils that have grown up in Soviet Russia will exist, in a greater or less degree, wherever there is a scientific government which is securely established and is not dependent upon popular support. It is possible nowadays for a government to be very much more oppressive than any government could be before there was scientific technique. Propaganda makes persuasion easier for the government; public ownership of halls and paper makes counterpropaganda more difficult; and the effectiveness of modern armaments makes popular risings impossible. No revolution can succeed in a modern country unless it has the support of at least a considerable section of the armed forces. But the armed forces can be kept loyal by being given a higher standard of life than that of the average worker, and this is made easier by every step in the degradation of ordinary labor. Thus the very evils of the system help to give it stability. Apart from external pressure, there is no reason why such a regime should not last for a very long time.

Scientific societies are as yet in their infancy. It may be worth while to spend a few moments in speculating as to possible future developments of those that are oligarchies.

In future such failures are not likely to occur where there is dictatorship. Diet, injections, and injunctions will combine, from a very early age, to produce the sort of character and the sort of beliefs that the authorities consider desirable, and any serious criticism of the powers that be will become psychologically impossible. Even if all are miserable, all will believe themselves happy, because the government will tell them that they are so.”

It is to be expected that advances in physiology and psychology will give governments much more control over individual mentality than they now have even in totalitarian countries. Fichte laid it down that education should aim at destroying free will, so that, after pupils have left school, they shall be incapable, throughout the rest of their lives, of thinking or acting otherwise than as their schoolmasters would have wished. But in his day this was an unattainable ideal: what he regarded as the best system in existence produced Karl Marx. In future such failures are not likely to occur where there is dictatorship. Diet, injections, and injunctions will combine, from a very early age, to produce the sort of character and the sort of beliefs that the authorities consider desirable, and any serious criticism of the powers that be will become psychologically impossible. Even if all are miserable, all will believe themselves happy, because the government will tell them that they are so.

A totalitarian government with a scientific bent might do things that to us would seem horrifying. The Nazis were more scientific than the present rulers of Russia, and were more inclined towards the sort of atrocities than I have in mind. They were said — I do not know with what truth — to use prisoners in concentration camps as material for all kinds of experiments, some involving death after much pain. If they had survived, they would probably have soon taken to scientific breeding. Any nation which adopts this practice will, within a generation, secure great military advantages. The system, one may surmise, will be something like this: except possibly in the governing aristocracy, all but 5 per cent of males and 30 per cent of females will be sterilized. The 30 per cent of females will be expected to spend the years from eighteen to forty in reproduction, in order to secure adequate cannon fodder. As a rule, artificial insemination will be preferred to the natural method. The unsterilized, if they desire the pleasures of love, will usually have to seek them with sterilized partners.

Sires will be chosen for various qualities, some for muscle, others for brains. All will have to be healthy, and unless they are to be the fathers of oligarchs they will have to be of a submissive and docile disposition. Children will, as in Plato’s Republic, be taken from their mothers and reared by professional nurses. Gradually, by selective breeding, the congenital differences between rulers and ruled will increase until they become almost different species. A revolt of the plebs would become as unthinkable as an organized insurrection of sheep against the practice of eating mutton. (The Aztecs kept a domesticated alien tribe for purposes of cannibalism. Their regime was totalitarian.)

To those accustomed to this system, the family as we know it would seem as queer as the tribal and totem organization of Australian aborigines seems to us. Freud would have to be rewritten, and I’m incline to think that Adler would be found more relevant. The laboring class would have such long hours of work and so little to eat that their desires would hardly extend beyond sleep and food. The upper class, being deprived of the softer pleasures both by the abolition of the family and by the supreme duty of devotion to the State, would acquire the mentality of ascetics: they would care only for power, and in pursuit of it would not shrink from cruelty. By the practice of cruelty men would become hardened, so that worse and worse tortures would be required to give the spectators a thrill.

Such possibilities, on any large scale, may seem a fantastic nightmare. But I firmly believe that, if the Nazis had won the last war, and if in the end they had acquired world supremacy they would, before long, have established just such a system as I have been suggesting. They would have used Russians and Poles as robots, and when their empire was secure they would have used also Negroes and Chinese. Western nations would have been converted into becoming collaborationists, by the methods practiced in France from 1940 to 1944. Thirty years of these methods would have left the West with little inclination to rebel.

To prevent these scientific horrors, democracy is necessary but not sufficient. There must be also that kind of respect for the individual that inspired the doctrine of the Rights of Man. As an absolute theory the doctrine cannot be accepted. As Bentham said: “Rights of man, nonsense; imprescriptible rights of man, nonsense on stilts.” We must admit that there are gains to the community so great that for their sake it becomes right to inflict an injustice on an individual. This may happen, to take an obvious example, if a victorious enemy demands hostages as the price of not destroying a city. The city authorities (not of course the enemy) cannot be blamed, in such circumstances, if they deliver the required number of hostages. In general, the “Rights of Man” must be subject to the supreme consideration of the general welfare. But having admitted this we must go on to assert, and to assert emphatically, that there are injuries which it is hardly ever in the general interest to inflict on innocent individuals. The doctrine is important because the holders of power, especially in an oligarchy, will be much too prone, on each occasion, to think that this is one of those cases in which the doctrine should be ignored.

Totalitariansim has a theory as well as a practice. As a practice, it means that a certain group, having by one means or another seized the apparatus of power, especially armaments and police, proceed to exploit their advantageous position to the utmost, by regulating everything in the way that gives them the maximum of control over others. But as a theory it is something different: it is the doctrine that the State, or the nation, or the community is capable of a good different from that of individuals, and not consisting of anything that individuals think or feel. This doctrine was especially advocated by Hegel, who glorified the State, and thought that a community should be as organic as possible. In an organic community, he thought, excellence would reside in the whole. An individual is an organism, and we do not think that his separate parts have separate goods: if he has a pain in his great toe it is he that suffers, not specially the great toe. So, in an organic society, good and evil will belong to the whole rather than the parts. This is the theoretical form of totalitarianism.

The difficulty about this theory is that it extends illegitimately the analogy between a social organism and a single person as an organism. The government, as opposed to its individual members, is not sentient; it does not rejoice at a victory or suffer at a defeat. When the body politic is injured, whatever pain is to be felt must be felt by its members, not by it as a whole. With the body of a single person it is otherwise: all pains are felt at the center. If the different parts of the body had pains that the central ego did not feel, they might have their separate interests, and need a Parliament to decide whether the toes should give way to the fingers or the fingers to the toes. As this is not the case, a single person is an ethical unit. Neither parts of a person nor organizations of many persons can occupy the same position of ethical importance. The good of a multitude is a sum of the goods of the individuals composing it, not a new and separate good. In concrete fact, when it is pretended that the State has a good different from that of the citizens, what is really meant is that the good of the government or of the ruling class is more important than that of other people. Such a view can have no basis except in arbitrary power.

More important than these metaphysical speculations is the question whether a scientific dictatorship, such as we have been considering, can be stable, or is more likely to be stable than a democracy.

Apart from the danger of war, I see no reason why such a regime should be unstable. After all, most civilized and semicivilized countries known to history have had a large class of slaves or serfs completely subordinate to their owners. There js nothing in human nature that makes the persistence of such a system impossible. And the whole development of scientific technique has made it easier than it used to be to maintain a despotic rule of a minority. When the government controls the distribution of food, its power is absolute so long as it can count on the police and the armed forces. And their loyalty can be secured by giving them some of the privileges of the governing class. I do not see how any internal movement of revolt can ever bring freedom to the oppressed in a modern scientific dictatorship.

But when it comes to external war the matter is different. Given two countries with equal natural resources, one a dictatorship and the other allowing individual liberty, the one allowing liberty is almost certain to become superior to the other in war technique in no very long time. As we have seen in Germany and Russia, freedom in scientific research is incompatible with dictatorship. Germany might well have won the war if Hitler could have endured Jewish physicists. Russia will have less grain than if Stalin had not insisted upon the adoption of Lysenko’s theories. It is highly probable that there will soon be, in Russia, a similar governmental incursion into the domain of nuclear physics. I do not doubt that, if there is no war during the next fifteen years, Russian scientific war technique will, at the end of that time, be very markedly inferior to that of the West, and that the inferiority will be directly traceable to dictatorship. I think, therefore, that, so long as powerful democracies exist, democracy will in the long run be victorious. And on this basis I allow myself a moderate optimism as to the future. Scientific dictatorships will perish through not being sufficiently scientific.

We may perhaps go further: the causes which will make dictatorships lag behind in science will also generate other weaknesses. All new ideas will come to be viewed as heresy, so that there will be a lack of adaptability to new circumstances. The governing class will tend to become lazy as soon as it feels secure. If, on the other hand, initiative is encouraged in the people near the top, there will be constant danger of palace revolutions. One of the troubles in the late Roman Empire was that a successful general could, with luck, make himself Emperor, so that the reigning Emperor always had a motive for putting successful generals to death. This sort of trouble can easily arise in a dictatorship, as events have already proved.

For these various reasons, I do not believe that dictatorship is a lasting form of scientific society— unless (but this proviso is important) it can become world-wide.

“I think the subject which will be of most importance politically is mass psychology. Mass psychology is, scientifically speaking, not a very advanced study, and so far its professors have not been in universities: they have been advertisers, politicians, and, above all, dictators. This study is immensely useful to practical men, whether they wish to become rich or to acquire the government. It is, of course, as a science, founded upon individual psychology, but hitherto it has employed rule-of-thumb methods which were based upon a kind of intuitive common sense. Its importance has been enormously increased by the growth of modern methods of propaganda. Of these the most influential is what is called “education.” Religion plays a part, though a diminishing one; the press, the cinema, and the radio play an increasing part.

What is essential in mass psychology is the art of persuasion. If you compare a speech of Hitler’s with a speech of (say) Edmund Burke, you will see what strides have been made in the art since the eighteenth century. What went wrong formerly was that people had read in books that man is a rational animal, and framed their arguments on this hypothesis. We now know that limelight and a brass band do more to persuade than can be done by the most elegant train of syllogisms. It may be hoped that in time anybody will be able to persuade anybody of anything if he can catch the patient young and is provided by the State with money and equipment. “

The Impact of Science on Society – Bertrand Russell