R. Buckminster Fuller and Albert Einstein

“At that time, there was a general myth that there were only 9 people in the world who could understand Einstein. They said they had looked at all the lists of the people who understood Einstein, and I was not on any of the lists in fact they didn’t find me on any list, of any authority, and they felt for me to be writing three chapters on Einstein would make Lippincott be accused of being a partner to charlatanry. That I was just a faker.”

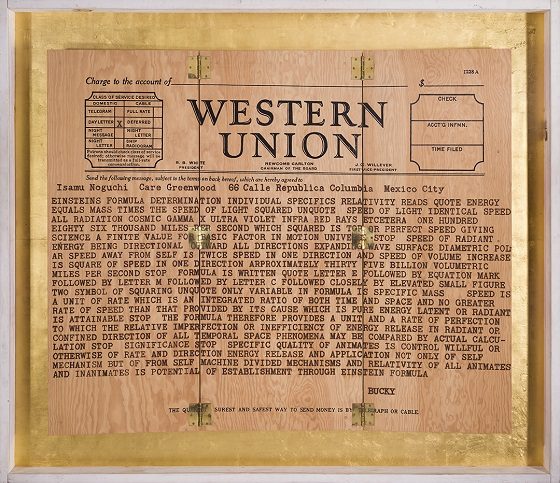

Tom Sachs, b. 1966 – Telegram, 2009

Gold leaf, pyrography, and synthetic polymer paint on plywood

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Sachs is not the only artist to be inspired by this remarkable telegram between these remarkable individuals.

WESTERN UNION

Isamu Noguchi Care Greenwood 66 Calle Republica Coumbia Mexico City

EINSTEINS FORMULA DETERMINATION INDIVIDUAL SPECIFICS RELATIVITY READS QUOTE ENERGY EQUALS MASS TIMES THE SPEED OF LIGHT SQUARED UNQUOTE SPEED OF LIGHT IDENTICAL SPEED ALL RADIATION COSMIC GAMMA X ULTRA VIOLET INFRA RED RAYS ETCETERA ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY SIX THOUSAND MILES PER SECOND WHICH SQUARED IS TOP OR PERFECT SPEED GIVING SCIENCE A FINITE VALUE FOR BASIC FACTOR IN MOTION UNIVERSE STOP

SPEED OF RADIANT ENERGY BEING DIRECTIONAL OUTWARD ALL DIRECTIONS EXPANDING WAVE SURFACE DIAMETRIC POLAR SPEED AWAY FROM SELF IS TWICE SPEED IN ONE DIRECTION AND SPEED OF VOLUME INCREASE IS SQUARE OF SPEED IN ONE DIRECTION APPROXIMATELY THIRTY FIVE BILLION VOLUMETRIC MILES PER SECOND STOP

FORMULA IS WRITTEN QUOTE LETTER E FOLLOWED BY EQUATION MARK FOLLOWED BY LETTER M FOLLOWED BY LETTER C FOLLOWED CLOSELY BY ELEVATED SMALL FIGURE TWO SYMBOL OF SQUARING UNQUOTE ONLY VARIABLE IN FORMULA IS SPECIFIC MASS SPEED IS A UNIT OF RATE WHICH IS AN INTEGRATED RATIO OF BOTH TIME AND SPACE AND NO GREATER RATE OF SPEED THAN THAT PROVIDED BY ITS CAUSE WHICH IS PURE ENERGY LATENT OR RADIANT IS ATTAINABLE STOP

THE FORMULA THEREFORE PROVIDES A UNIT AND A RATE OF PERFECTION TO WHICH THE RELATIVE IMPERFECTION OF INEFFICIENCY OF ENERGY RELEASE IN RADIANT OR CONFINED DIRECTION OF ALL TEMPORAL SPACE PHENOMENA MAY BE COMPARED BY ACTUAL CALCULATION STOP

SIGNIFICANCE STOP

SPECIFIC QUALITY OF ANIMATES IS CONTROL WILLFUL OR OTHERWISE OF RATE AND DIRECTION ENERGY RELEASE AND APPLICATION NOT ONLY OF SELF MECHANISM BUT OF FROM SELF MACHINE DIVIDED MECHANISMS AND RELATIVITY OF ALL ANIMATES AND INANIMATES IS POTENTIAL OF ESTABLISHMENT THROUGH EINSTEIN FORMULA

BUCKY

R.Buckminster Fuller and Albert Einstein

The following are excerpts taken from a talk by R. Buckminster Fuller, a 20th century inventor and visionary on his meeting with Albert Einstein in 1936. Taken from a series of lectures Bucky gave in January 1975, Everything I Know.

When I interpret Einstein and talk about him, which I do very frequently, I did have his personal approbation of my capability to do so. I am giving you then, a hypothetical example of what Einstein employed as a strategy of thinking which brought about Bridgman’s development of the word “operational.”

But, what was interesting to me was that I heard from this man, two years before the theoretical fission is envisaged, that he didn’t have the slightest idea of anything that he had ever done having even the slightest practical application. Because the first practical application of the Enrico Fermi pile completely validated his theory of the amount of energy that was being stored in a given mass. So, it was the very essence of what was going on. So the first practical application was Hiroshima. And having heard that from that man just before it occurred, I realized the unhappiness and the consternation that he experienced when the first practical application was Hiroshima. In fact, his last days were spent greatly devoted to trying to get the scientists to realize their responsibilities, and how they were being exploited. And his consternation brought about the development of the Association of Atomic Scientist, and the publishing of the ATOMIC SCIENTIST BULLETIN, and so forth.

And then there was a whole set of events which followed this which people are very familiar with. And then the German Jewish scientists getting the word as quickly as they could out of Germany because they thought it would be used immediately for armaments in Germany, and the word did come to America. And there were theoretical studies, and then came the conclusion of the scientists that fission was actually possible. So, there was the quandary of the scientists because politicians don’t listen to scientists on how to get word to President Franklin Roosevelt. So they all decided that Einstein was by far the most highly accredited of the scientists. So they asked him to go see Franklin Roosevelt. And Franklin Roosevelt did appropriate what was at that time an incredible amount of money, $85 billion for the great Manhattan project. And then through the Enrico Fermi pile and all the history which most of you know.

His equation had not as yet been validated, as it was later, by fission, at the time that I was writing. Anyway, he said he did approve of those two chapters of my chapter explaining how his philosophy was interpreted into his action and thinking. But he said, the third chapter about Mrs. Murphy’s horsepower and his words were I’ll imitate him, because I can remember this so very well. And he was very gentle, and he said of this third chapter: “Young man, you amaze me. I cannot conceive of anything I have ever done having the slightest practical application.” And he went on to explain that he had evolved his thoughts as possibly being useful to the astronomers, to the astro-physicists, to the cosmogeners and the cosmologists, but that it would have any practical application none. And, at any rate, he did approve, and they did go on with the publishing of the book. This was very interesting, because this meeting occurred about a year and a half before Hahn and Stresemann discovered theoretical fission.

Then I had a third chapter in which I said that, historically, great scientists, individual scientists, make discoveries the academy doesn’t accept right away, but later on they do accept. Then it gets to be in the schools, then it gets to be in the general atmosphere of everybody’s thinking. At this point engineers and inventors within that atmosphere of thinking make some invention, and then gradually some industry takes on that invention; and that takes quite a while. There is a lag. Finally, various things are being produced and they bring about a new environment under which social changes have to occur, and politics, then, has to take care of the take up on the new orientation of man all brought about indirectly from the original scientist’s thinking. And, I said, again my third chapter was I developed a hypothetical picture of how humanity would be living. It was called “E=MC to the second power equals Mrs. Murphy’s Horse Power,” and then I was looking at the every-day life of Mrs. Murphy under the circumstances of everybody being completely convinced of the validity of Einstein’s thinking.

He immediately excused himself from the company, and took me out to a little library that was just off the main hall of the apartment, and on the library table was my typescript under a light, and we sat down on either side of this desk. And he said that he had been over my typescript and that he was writing to my publishers to say that he approved of my interpretation of his thoughts, and the way I had explained his translation of philosophy. A philosophy of his which had been published in the New York Times Sunday magazine in New Year, 1930, called “The Cosmic Religious Sense,” (see below) and it was a very, very inspiring piece, and I had asked the publishers if I could quote it in my book, and I did. Having then this chapter on his philosophy, I then had another chapter on the way that I felt he had interpreted it into, how he applied that philosophy to all his own grand personal strategy of life, and how he came about developing his thoughts and his equation.

And so, I was a little stunned, and still quite young, and so I simply wrote back, in a sense quite facetiously, to Lippincott, saying that Dr. Einstein has just come to America, and was in Princeton at the newly organized Institute for Advanced Study. And I suggested that they send my typescript to him that he would be the best authority. I really did not think they would take me seriously about that, and I forgot all about that. And it was about six months later, I had a telephone call from a doctor in New York, and he said my friend Dr. Albert Einstein is coming in to spend the weekend with me, and he has your typescript, and he would like to talk to you about it. And, could I possibly come on Sunday evening to his apartment in New York. So, you can imagine, I didn’t have any engagements that would interfere! And I had very few engagements in those days nobody wanted to talk to me. And, I did come then, to the apartment. He was a wealthy man, and he had a large living room, and in more or less dramatic kind of style, people were sitting around the walls of the room, and he was sitting pretty much in the middle. I think they might have later on played music for him. At any rate, when I came in I was brought then to this long room, up to meet him. And I really had, I don’t know how much psychological was in me, but I really had the most extraordinary feeling about being in a presence of almost an aura of him.

The example that I am going to give you is my own invention, but I did include Einstein and Einstein’s philosophy, and my own interpretation of how he came to develop his equation and other of his strategies, in my first book NINE CHAINS TO THE MOON, and because I had three chapters on Einstein, my publishers who were Lippincott of Philadelphia at that time, in the mid-30’s, around 1935, said that they found I had three chapters on Einstein. And they were, at that time, there was a general myth that there were only 9 people in the world who could understand Einstein. They said they had looked at all the lists of the people who understood Einstein, and I was not on any of the lists in fact they didn’t find me on any list, of any authority, and they felt for me to be writing three chapters on Einstein would make Lippincott be accused of being a partner to charlatanry. That I was just a faker.

Religion and Science

By Albert Einstein

(The following article by Albert Einstein appeared in the New York Times Magazine on November 9, 1930 pp 1-4. It has been reprinted in Ideas and Opinions, Crown Publishers, Inc. 1954, pp 36 – 40. It also appears in Einstein’s book The World as I See It, Philosophical Library, New York, 1949, pp. 24 – 28.)

Everything that the human race has done and thought is concerned with the satisfaction of deeply felt needs and the assuagement of pain. One has to keep this constantly in mind if one wishes to understand spiritual movements and their development. Feeling and longing are the motive force behind all human endeavor and human creation, in however exalted a guise the latter may present themselves to us. Now what are the feelings and needs that have led men to religious thought and belief in the widest sense of the words? A little consideration will suffice to show us that the most varying emotions preside over the birth of religious thought and experience. With primitive man it is above all fear that evokes religious notions – fear of hunger, wild beasts, sickness, death. Since at this stage of existence understanding of causal connections is usually poorly developed, the human mind creates illusory beings more or less analogous to itself on whose wills and actions these fearful happenings depend. Thus one tries to secure the favor of these beings by carrying out actions and offering sacrifices which, according to the tradition handed down from generation to generation, propitiate them or make them well disposed toward a mortal. In this sense I am speaking of a religion of fear. This, though not created, is in an important degree stabilized by the formation of a special priestly caste which sets itself up as a mediator between the people and the beings they fear, and erects a hegemony on this basis. In many cases a leader or ruler or a privileged class whose position rests on other factors combines priestly functions with its secular authority in order to make the latter more secure; or the political rulers and the priestly caste make common cause in their own interests.

The social impulses are another source of the crystallization of religion. Fathers and mothers and the leaders of larger human communities are mortal and fallible. The desire for guidance, love, and support prompts men to form the social or moral conception of God. This is the God of Providence, who protects, disposes, rewards, and punishes; the God who, according to the limits of the believer’s outlook, loves and cherishes the life of the tribe or of the human race, or even or life itself; the comforter in sorrow and unsatisfied longing; he who preserves the souls of the dead. This is the social or moral conception of God.

The Jewish scriptures admirably illustrate the development from the religion of fear to moral religion, a development continued in the New Testament. The religions of all civilized peoples, especially the peoples of the Orient, are primarily moral religions. The development from a religion of fear to moral religion is a great step in peoples’ lives. And yet, that primitive religions are based entirely on fear and the religions of civilized peoples purely on morality is a prejudice against which we must be on our guard. The truth is that all religions are a varying blend of both types, with this differentiation: that on the higher levels of social life the religion of morality predominates.

Common to all these types is the anthropomorphic character of their conception of God. In general, only individuals of exceptional endowments, and exceptionally high-minded communities, rise to any considerable extent above this level. But there is a third stage of religious experience which belongs to all of them, even though it is rarely found in a pure form: I shall call it cosmic religious feeling. It is very difficult to elucidate this feeling to anyone who is entirely without it, especially as there is no anthropomorphic conception of God corresponding to it.

The individual feels the futility of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. Individual existence impresses him as a sort of prison and he wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole. The beginnings of cosmic religious feeling already appear at an early stage of development, e.g., in many of the Psalms of David and in some of the Prophets. Buddhism, as we have learned especially from the wonderful writings of Schopenhauer, contains a much stronger element of this.

The religious geniuses of all ages have been distinguished by this kind of religious feeling, which knows no dogma and no God conceived in man’s image; so that there can be no church whose central teachings are based on it. Hence it is precisely among the heretics of every age that we find men who were filled with this highest kind of religious feeling and were in many cases regarded by their contemporaries as atheists, sometimes also as saints. Looked at in this light, men like Democritus, Francis of Assisi, and Spinoza are closely akin to one another.

How can cosmic religious feeling be communicated from one person to another, if it can give rise to no definite notion of a God and no theology? In my view, it is the most important function of art and science to awaken this feeling and keep it alive in those who are receptive to it.

We thus arrive at a conception of the relation of science to religion very different from the usual one. When one views the matter historically, one is inclined to look upon science and religion as irreconcilable antagonists, and for a very obvious reason. The man who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation cannot for a moment entertain the idea of a being who interferes in the course of events – provided, of course, that he takes the hypothesis of causality really seriously. He has no use for the religion of fear and equally little for social or moral religion. A God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to him for the simple reason that a man’s actions are determined by necessity, external and internal, so that in God’s eyes he cannot be responsible, any more than an inanimate object is responsible for the motions it undergoes. Science has therefore been charged with undermining morality, but the charge is unjust. A man’s ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death.

It is therefore easy to see why the churches have always fought science and persecuted its devotees.On the other hand, I maintain that the cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research. Only those who realize the immense efforts and, above all, the devotion without which pioneer work in theoretical science cannot be achieved are able to grasp the strength of the emotion out of which alone such work, remote as it is from the immediate realities of life, can issue. What a deep conviction of the rationality of the universe and what a yearning to understand, were it but a feeble reflection of the mind revealed in this world, Kepler and Newton must have had to enable them to spend years of solitary labor in disentangling the principles of celestial mechanics! Those whose acquaintance with scientific research is derived chiefly from its practical results easily develop a completely false notion of the mentality of the men who, surrounded by a skeptical world, have shown the way to kindred spirits scattered wide through the world and through the centuries. Only one who has devoted his life to similar ends can have a vivid realization of what has inspired these men and given them the strength to remain true to their purpose in spite of countless failures. It is cosmic religious feeling that gives a man such strength. A contemporary has said, not unjustly, that in this materialistic age of ours the serious scientific workers are the only profoundly religious people.

“I cannot imagine a God who rewards and punishes the objects of his creation, whose purposes are modeled after our own — a God, in short, who is but a reflection of human frailty. Neither can I believe that the individual survives the death of his body, although feeble souls harbor such thoughts through fear or ridiculous egotisms.” (Albert Einstein, obituary in New York Times, 19 April 1955)