Long before the Bible existed as it does today, copies of the Apostle Paul’s letters floated around the ancient world.

Paul (formerly Saul) had been a persecutor of early Christians. After Jesus was crucified, Paul made it his personal mission to bring ruin to the followers of what he believed was a false Messiah. But in the year 31 or 32AD, Paul had an encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus – he writes of the risen Jesus appearing to him – and became a Christian.

From that moment on, Paul devoted himself to the promotion of Christianity – travelling far and wide to establish small groups of converts: Christianity’s first ‘churches’. Paul appointed leaders of each group and moved on to the next town. But he kept in touch with these groups through letters, in which he gave advice, rebuked, offered praise and pleaded with them to remain faithful to the message of Jesus they had learned from him. A handful of these letters – or “epistles” – have survived.

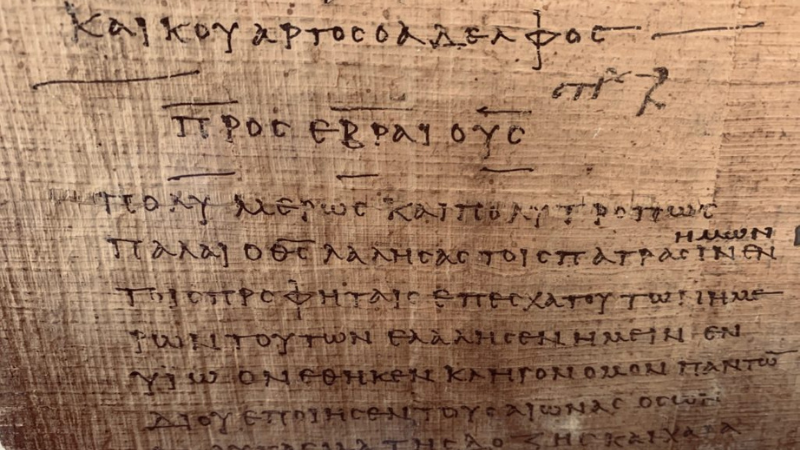

The earliest copy of Paul’s letters is called P46 and dates to around the 3rd Century AD. The letters, directed to Rome, Ephesus, Galatia and his second letter to Corinth, are on strips of papyrus plant that had been pressed, dried and cut to size.

Artefacts like P46 give historians the opportunity to test whether the Bible as we know it today is the same as the writings of the early Christians. Did things get changed along the way? How can we be sure if what you’re reading in your Bible today is the same as what was intended 2000 years ago?

“There are differences – usually really small ones.” says John Dickson, who travelled to the University of Michigan’s Papyrology Department to lay his hands on the ancient manuscripts.

“In P46 you get some weird contractions of words, especially holy words like ‘God’, ‘Spirit’, ‘Jesus’, ‘Christ’ – they’re reduced to just a couple of letters, and then the subscribe ‘overlines’ these letters (which is like someone underlining them today).

“Or right at the end of Romans, in a modern Bible, reads: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with you”. But in P46, it reads “The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you’. No Christ.”

One pretty big difference at the end of Romans does raise some questions.

In most of our Bibles, the letter to the Romans ends with a lofty paragraph called the doxology. It reads:

“Now to him who is able to establish you in accordance with my gospel, the message I proclaim about Jesus Christ, in keeping with the revelation of the mystery hidden for long ages past, 26 but now revealed and made known through the prophetic writings by the command of the eternal God, so that all the Gentiles might come to the obedience that comes from[f] faith— 27 to the only wise God be glory forever through Jesus Christ! Amen.”

That whole paragraph, says John Dickson, doesn’t appear at the end of Romans in P46. It simply ends with a greeting from Quartus (see Romans 16:23) and then the very next line is straight into the next letter to the Hebrews.

“The missing paragraph in P46 actually appears at the end of chapter 15, rather than in chapter 16 as our modern Bibles have it. So it’s not missing. We don’t know why. Other later manuscripts have it at the end of the letter. But we may never know why the P46 scribe put it at the end of chapter 15 when most of the other manuscripts we have place it at the end of chapter 16. But either way, it’s there.”

“Here’s the cool thing about New Testament studies,” says Dickson. “We have so many copies of the New Testament! We have hundreds of manuscript fragments and huge portions from different periods of Roman history and different parts of the empire. So you can line them up all together and work out where the variations are.

The several writings of the New Testament were published to the world at various times during the latter part of the first century of the Christian era; the art of printing was first practised in some German city in the middle of the fifteenth century: the first fruit of typography, the beautiful Latin Bible known as Cardinal Mazarin s, of which we have a copy in the British Museum, appeared at Mentz scarcely before A.D. 1455. During that long period of fourteen hun dred years, through the fading light of the decline of ancient literature, through the deep gloom of the middle

ages, even till the dawn of better days had almost brightened into the morning sunshine of the revival of learning, Holy Scripture was preserved and its study kept alive in the same way as were the classical writings of Greece and Rome, by means of manuscript copies made from time to time as occasion required, some times by private students, more often by professional scribes called calligrapliers or fair-hand writers, who were chiefly though by no means exclusively members of religious orders, priests or monks, carrying on their honourable and most useful occupation in the scripto rium or writing-chamber of their convents. or letters will have been mistaken by the copyist, or his eye may have wandered from one line to another, or he may have omitted or repeated whole sentences, or have fallen into some other hallucination for which he would find it hard to account even to his own mind. Human imperfection will be sure to mar the most highly-finished performance, and to leave its mark on the most elaborate efforts after accuracy.