the following is from

1983

“Believing that you’ve become the center of the universe… in a sense may be true. But in an actual, practical sense of our four-dimensional world, this is a disaster of the first order.

I mean, there are truths that are unuseful. And there are also truths for which a particular culture has no slot. We have no real slot for people who wish to become the center of the universe.”

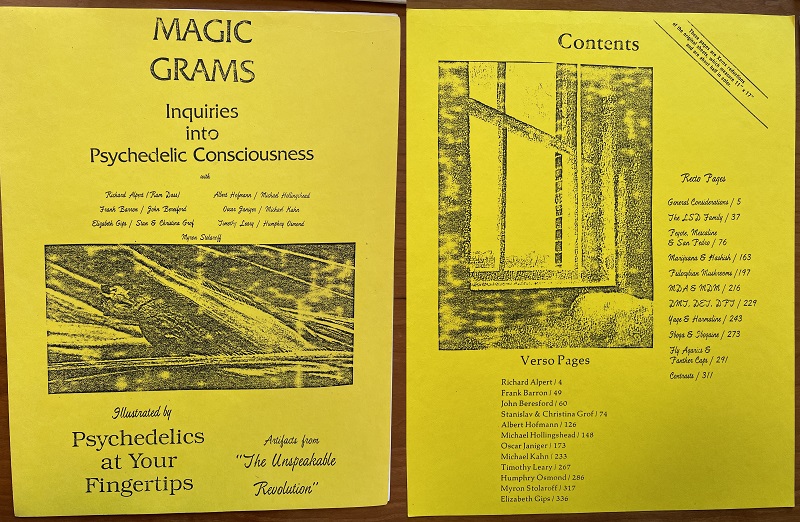

Schizophrenia: A New Approach

Humphry Osmond and John Smythies

1952

In 1950, Osmond began working with psychedelics (particularly mescaline & LSD) while looking for a cure for schizophrenia at Weyburn Mental Hospital in Saskatchewan, Canada. During this time, he suggested that mescaline allowed a normal person to see through the eyes of a schizophrenic and suggested that it be used to train doctors and nurses to better understand their patients. His research attracted the attention of Aldous Huxley, who volunteered to be a subject. In May 1953, Osmond introduced Huxley to mescaline for the first time, an experience described in Huxley’s Doors of Perception.

Osmond was part of a community of therapists who worked with mescaline and LSD from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s. He and Al Hubbard developed a method of using LSD to cure alcoholics of their addiction by attempting to mimic the experience of the extreme low of delium tremens. Later, Osmond and Hubbard realized that psychedelics could be used as a psychotherapeutic tool without attempting to mimic psychotic states.

Osmond served on the board of The Commission for the Study of Creative Imagination, founded by Al Hubbard, along with Abram Hoffer, Sidney Cohen, Aldous Huxley, Gerald Heard, and others.

Osmond experienced mescaline in the early 1950s, and in May 1950 provided this to Aldous Huxley in Los Angeles. Huxley’s report to Osmond, The Doors of Perception, remains a milestone in psychedelic history, as does the word that Osmond coined — “psychedelic.” Currently, Osmond works as a psychiatrist in Tuskaloosa, Alabama.

He is co-author of The Hallucinogens (Academy Press), co-editor of The Psychedelics – The Uses and Implications of Hallucinogenic Drugs (Anchor Books), and author of Understanding Understanding.

Osmond’s interest in this field grew out of a fascination with schizophrenia and alcoholism. His story starts earlier, however — shortly after he went into the Navy once he had qualified for medicine at Guys Hospital in London in 1942. He had six weeks of training, and then went to Scotland and then in a convoy into the North Atlantic. It took three weeks to get across and on the way back he got caught in the climax of the battle of the Atlantic.

It took 25 years before I discovered really why this convoy has been so fascinating to historians. It was when Donyits threw in 40 of his U-boats and caught us while we were building up for the invasion. It’s now called the “Battle of St. Patrick’s Day,” in which we were really heavily worsted. But this was the beginning of a series of great triumphs against the U-boats. We sunk 100 U-boats in 100 days. Those in the film Das Boot were our opponents.

Then I had this very, very unusual experience of being in the House of Commons in Parliament 24 hours after landing, and hearing them debating this great disaster. Very few people have actually been able to go directly from war to the legislature to hear what they are doing there, so it was a very great and interesting lesson.

In the Navy, when I had been at sea a year, the question came। what was I to do. Because there was a general policy there that young naval officers — medical doctors — if they spent more than about a year or two at sea on their own probably would become alcoholics. I don’t know whether it was true or not, but that was the Admiralty’s fear.

So they wrote to ask me what I would d0, and I had seen a number of cases — both going from ship to ship, and in our own ship/of people who clearly were suffering from psychiatric conditions. I treated a few of them successfully, and I had seen the impact of these illnesses, particularly on ships at sea, and the impact on the young men — many of them had been sunk under dreadful conditions — trying to come to terms with the great misfortunes from which they had suffered.

Now and again, we would get someone who was, in fact, gravely mentally ill. They had a notable effect upon the rest of the crew. And, after all, if someone goes over the side suddenly believing that they are an angel or a merman or something like this — sailors, first, as I was pointing out yesterday, Friday the 13th, are naturally superstitious. But added to this, they have this sort of idea that they are a very special breed of animal. And apparently this thing is sort of contagious.

Almost all of our people were landsmen they weren’t sailors at all. But in a remarkably short time, they had picked up the sailors’ superstitions. Presumably the sea and its roughness, and its strangeness and the fact that we haven’t been aquatic for some time, impresses these ideas upon us.

So I said that I wanted to go into psychiatry and I was told that there were absolutely no openings. I was very sorry about this, and I thought otherwise I might go in for tuberculosis — which was at that time still quite a going concern, because they hadn’t brought in the great antibiotics yet.

So I happened to be in a club in London and I met a man over a bar. I found he was at one of the naval psychiatric hospitals. I told him where I was, and he said, “What are you going to do when you leave the sea, which you will inevitably do?” since he (knew I had been at sea over a year.)

“Well, what I would like to do would be to go into psychiatry. Well, why don’t you?”

I explained to him, and he said, “I don’t know about that. I’ve been talking to Surgeon Captain Curran, who is the head of Naval Psychiatry, and he’s been telling the Admiralty that they would love to have young psychiatrists, but no one wants to go in for it.”

So I wrote a letter to him, and he was always very amused by this. He said, “That just shows what bureaucracies are like.” They had been telling him he must get as many yoyng psychiatrists with as possible because after the invasion of Europe and the Far East things, they were going to need far more than the actual trained psychiatrists could conceivably supply.

I had been in the Atlantic in all of 1943, and in 1944 we’d been going up and down the channel. I think it was about the 14th of April when I was suddenly moved. I was extremely upset about this. First, I knew all the people, and secondly, I knew perfectly well that if there was an invasion with the kind of casualties we were expecting — which were 30% — that I would then be moved to another ship where I didn’t know anyone, and one of the ways of staying alive in a ship was to know the crew, and to know where to get off and when to get off.

So anyway I was sent off, after some delays and uncertainties to his hospital called Berigernia. There I met a man who later became my boss and I spent a very peculiar six weeks crash course. Why this has bearing on this is in the course of this I saw a number of people who were schisophrenic.

I had seen a few before. My first girl I ever recall seeing was a young lady who came in who looked like the movie star Diana Derby — I don’t know, you probably hardly remember her. She was a singing movie star of sixteen, and people were very fond of her — and quite rightly so, too. She sang beautifully and looked very attractive. This girl looked like her, and she came in to see me and I said, “What’s the matter?”

She said, “I looked in the mirror this morning and I saw an elephant.” I looked at her and I said, “What do you mean?”

And she said, “I looked in the mirror this morning and I saw what looked like an elephant.” I said, “Well, what was that?” She said, “Well, that’s me.” I said, “I don’t think that’s you at all.” And she said, “Well, that’s what I saw in the mirror.”

I was very, very puzzled about this, so I went to my chief and said, “What could that be?”

He said, “Well, you know she has schizophrenia.” I said, “Well, what’s that?”

This question kept popping up for a time and when I raised it, and he had seen quite a number of them, he said to me, “Well, there’s only one person who really knows what this thing is like, and this is a chap called Anthony Hampton,” who was, in fact, a Jungian analyst running a little officers.’ hospital.

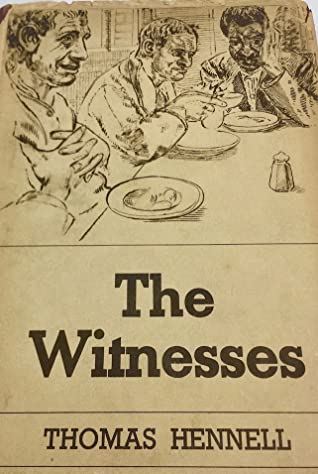

I went over to see him, and I drank a lot of very good champagne cider and listened to his thing. He was a very nice man, and he told me that the real way to learn about schizophrenia was to read a book written by one of his patients called The Witnesses, by Thomas Hennell.

“The Witnesses,” he said,”will tell you what it’s like to be from the inside of schizophrenia.”

“The Witnesses,” he said,”will tell you what it’s like to be from the inside of schizophrenia.”

He said, “If you don’t understand that, you don’t understand anything.” He said, “I can assure you it’s not an easy thing to understand. The books really do not tell you what this is like.” He said, “It’s not that they do not want to. It’s that it’s extremely difficult.”

I was very impressed by this. I tried to get this book — I spent about four or five months getting it. Publishers Row in England in the city of London had been burned out and most of these huge quantities of books had been burned. But I found one secondhand and I started to read it. I read it on a number of occasions.

Since, my old friend had told me this was terribly important, I read it with a great attention, but it was still extremely difficult to reconcile these very strange remarksi how, as the illness began, the strange significance of objects, the unusual noises in the night, the uncertainty of his self-identification, the feeling of destiny, and then this extraordinary walk that he makes to Oxford in which he walks down the road, and the road seems to be going into eternity, the people on the edges of it look strange and look at him significantly. And then as he goes on as night approaches, the fields begin to boil and the constellations swing overhead and he is suddenly seized by either a group of secret policemen or something, who put him into a van filled with meat, so he believes, and then take him off to prison. And then these various things happen.

So I read this assiduously. I thought about it a great deal. And then, about a year after that, I was sent out to Malta to fill one of these positions temporarily that the Navy was doing, since they were now preparing — this was in 1950 the war in Germany is coming to an end, the army are beginning to withdraw their people in order to get ready for the Par Eastern campaign. The idea was, as far as I know, that the younger psychiatrists would go out to the periphery and then would be leap-frogged towards the Par East. In fact, of course, it all turned out very differently.

I spent almost 2 years there, since I was a regular naval officer. And there I saw substantial numbers of people with schizophrenia. I became deeply interested in this. Remembering what Hampton told me, I would talk to them but it still seemed to me it didn’t really make any great sense.

And I went back to my old hospital in London, Guys Hospital, spent a short time there doing some neurology. And then my chief in the Navy at St. George’s, who’s now become a professor of psychiatry there, took me over there and I became his first assistant. I became able again to see lots of schizophrenics and treat them with deep insulin, talk with them and ponder about them.

During this time, we had a very junior resident come along — a chap called John Smythies. And John — he’d just come out of the Navy. At this time he was extremely difficult, he had had a very, very strange upbringing. He was brought up in India like a young — I don’.t think he would even object to my saying this — like a young princeling in an Indian state. His father was the chief forester there, a sort of administrator. They made most of their money out of their forests.

To the age of seven he was brought up, you know, with numerous Indian amors or something looking after him. And then he was suddenly shipped to an English — what we call a “preparatory school,” which is not the same as ones here — where he put on the same airs as he had as a young princeling, and was beaten up mercilessly.

To further his education, he once or twice went back, I think, to India, longing to stay there, of course, and then was sent back again. He was then sent to an English public school, where life was even more dismal. So he spent from the age of seven until about eighteen living an extremely miserable life with this paradise lost, you know.

Then, when he was eighteen, he went up to Cambridge and suddenly discovered a marvelous life again. He then went into the Navy, and the Navy, as he said, was very much like going back to his school Rugby. He said that there were all these constraints which Cambridge had removed him from, and he was extremely miserable.

Then when he came back to St. George, he was recovering his confidence again and he told his teachers that his interest in psychiatry was largely due to his interest in philosophy — which didn’t at all impress them. The idea that anyone would want to practice psychiatry with the mere intention that it was to be a sort of annex to philosophy filled them with vexation. It was not their view of what residents did.

As a matter of fact, many people felt this was very pretentious. I got to know John very well. It wasn’t at all pretentious. The only thing pretentious about it — John was very well read, he was very intelligent, he was deeply interested in this — the only thing pretentious about it was the particularly straightforward way in which he put it. He would say, “It is obvious that this is so.” “It’s obvious that the brain can’t work that way.” And people for whom this wasn’t obvious didn’t like this very much.

We got to know each other and, in the course of this, John told me about his interest in parapsychology as part of this general idea of how the mind works — which is, after all, very reasonable. Parapsychology was quite well established there. We had in London the Society for Psychical Research, which has an enormous amount of data, and it seemed not unlikely that things like this happened.

I, myself, come from a family of people — on one side of Scottish people, who had members of the family who had “second sight,” as it was called. And it wasn’t looked at as the least bit unusual. There are family stories about things like this, and I never thought they are impossible. I met patients to whom this had happened, and one doesn’t neglect these kind up. of things. They may be mistaken! they may not.

Anyway, in the course of following these various things, he got a book by a man called Rouhier, a Frenchman, called Le Peyotl. In the course of doing this, he found a picture of a chicken waving a tricolor — a very French idea, this as one of the hallucinations — and then, shortly after, a formula o mescaline.

He brought it along to me on a May morning in 1950, I think it was, and he said, “What does this remind you of?” I said, “It reminds me of something too, and I can’t think what.”

We had a medical student called Julian Redmill, who had been a biochemist, and we asked him what it looked like to him. And he said, “It looks either like thyroid or it looks like adrenaline.”

On the basis of that, John got some mescaline. It was quite easy to get. There was a firm called Lights in London. Very, very cheap — I think it was about less than a dollar a gram or something, very modest. Of course, on our pay then it wasn’t so modest. It was very good stuff, beautiful. And he took some, and he got one of his friends to take this.

We wrote a paper out of this. John went up to see a chap I called John Harley-Mason at Cambridge. And Harley-Mason, who is a very well-known professor of chemistry, told him that, indeed, this was not a fantastic idea. It was conceivable that adrenaline might become a mescaline-like substance by a process known as “transmethylation” — that is, you would add on methyl groups.

You would turn your own adrenaline into mescaline in a very crude way. Anyway, the only snag was that this was not known to occur in any animal. Transmethylation was a regular process in plants, but not in animals.

Well, of course, within about a year, it was found to occur in the squid, and, of course, within three or four years, it was found to occur in humans. It is now one of the main processes in membrane transfer and all these things. Transmethylation seems to be a crucial process. Our paper, that we then wrote, has, strangely enough, become among the most cited papers, and on its thirty-year anniversary, John has just written a paper putting right some of the people who’ve written.

There’ve been various ideas. Some of the more chemically- biased felt that it was John Harley-Mason who made this discovery. Now John and I know exactly what the discovery was. We know that he made the initial observation, I encouraged him in this, we then got hold of Redmill, and then we got hold of Harley-Mason.

But what we also did was to relate the findings of mescaline, which we initially got from reports, and then, from our own experiences — we related this to the symptoms of schizophrenia. And in the table that we wrote, you can see that there are many, ad many correspondences. At that time we didn’t know the term “model psychosis,” but we pointed out that there are these many similarities.

At this time I got a job in Canada because I thought I wanted to be able to see — I had seen a good many schizophrenics, I wanted to see many more, so we could, really, as it were —

Had you already written **On Being Mad”?

No, no. This is how “On Being Mad” got written. I thought, however, that before doing it — since John had taken mescaline and given it to other people — I better take it myself. And so I went up to John’s flat, where he and Verma, who was his girlfriend and who’s now his wife, were living. I said that I thought I ought to take it and we both agreed, and he gave me 400 mg. of mescaline. That’s where “On Being Mad” came from.

Now we were also in the process of writing this paper “Schizophrenia: A New Approach,” and both of us became very much * convinced that if anything like this happened, it would be a “ far more economical account of what was actually happening.

And even if this was not so, the mescaline experience, as many people had said before, gives you a far clearer idea of what patients are talking about.

When people do all this business about LSD and these things not being identical with schizophrenia, well, who the hell said they were? They become extremely close if you give it to someone without their knowing it — which is a dastardly thing to do. But the fact is, as Moreau de Tours found with hashish in the 1840s, if you give your residents or take yourself this, and see for yourself, you are left in no doubt that many of the strictures that are made of our patients — about what they ought or ought not to do — unless you know exactly what they are experiencing ‘and you know exactly what kind of person they are, it’s quite unclear what they ought or ought not to do.

It’s quite clear, however, that they ought to be strongly encouraged to understand something has gone seriously wrong, and that their sort of self-remedies will not necessarily work. That is, doing absolutely nothing, or believing that you’ve become the center of the universe and all these things — in a sense, in a philosophical and theological sense, this in a sense may be true. But in an actual, practical sense of our four-dimensional world, this is a disaster of the first order.

I mean, there are truths that are unuseful. And there are also truths for which a particular culture has no slot. We have no real slot for people who wish to become the center of the universe. We are not really well set up to have a charismatic dictator. The whole aim of the Constitution of the United States and the non-Constitution in Britain is to avoid this misfortune.

Anyway, we wrote this paper — “Schizophrenia A New Approach.” We had great difficulty initially in getting it published. It would never have been published if it had not been for an aberrant editor of the Journal of Mental Science, Dr. G.W.T.H. Fleming, who, in spite of advice from various people, published it. And so, in 1952, it was published.

I had gone off to Saskatchewan by then. I had met my other old friend, Abram Hoffer. He at this time was a biochemist-physician who was becoming a psychiatrist, and he, indeed, became one not very long afterward. He was tremendously interested at first, but, as he said, he had great difficulty in understanding my speech. He wondered why I didn’t speak English.

But he attuned himself to this, and then we eventually — he told me that one of the reasons that he became so interested in this was that he had been down in the United States. He had been around, seeing all the centers. The only things they were interested in was either psychoanalysis or else steroid hormones, with one exception. This was the great Heinrich Kluverr of Chicago. And Kluver told him, he said, “Mescaline is the most interesting substance there is and I advise you to take a look at it.”

When I came along, Kluver was one of our initial references, and when I told him this, he became much intrigued. We got some mescaline, and, as he said, the more he thought about it the more feasible it became.

Within about a year, we had got the idea that not only was there this family of potential whatever-you-like — hallucinogens, psychedelics, psychotomimetic substances — but there were other families of them. Things like the amenochromes, which are probably much better models for some schizophrenias. They take the edge off somewhat differently. After all, we are thinking of shifting a few molecules one way or another in this immensely complex piece of equipment which in some extraordinary way gives us access to the universe. Or, perhaps, for all we know, to other universes — which is now much more respectable, I believe, now than then.

Anyway, in 1952 we went down to New York to the New York Psychiatric Institute and gave them a talk there. We had already worked out that the amenochromes were another possibility — these are the indolized relatives of adrenaline. You are not popping on here transmethyl groups j you are turning it into a ring, and making something, as we showed in the paper, awfully like LSD and awfully like harmine and these sort of things, and with a resemblance to mescaline,

And so anyway. Heinrich Welch, one of their famous chemists said, “Haven’t you thought about adrenochrome?” We had to admit that we had, and that was why we had to go back and test it.

This is one of the very interesting things. It shows, in fact, the human brain is probably as good a way of picking these things up as any way. We saved years of discussions about whether rats can climb strings, you know, at the right speed, by taking it ourselves and seeing.

Now although this is the standard way of doing it with many, many medical experiments, it is still very poorly received, in a way different from our forebearers. Chaps like Weir Mitchell and James and others had absolutely no doubt that self-experiment would tell you a great deal more quickly. But now we believe in self-experiment with poor rats, cats, dogs and monkeys, who, of course, can’t actually speak. So it’s very much better to take human beings who can.

When you realize also that human beings have always been doing this, and that, provided that the stuff isn’t deadly poisonous, that they will probably become quite interested in doing this. Anyhow, we are always ingesting huge quantities of poisons like alcohol or caffeine and things like this. We shouldn’t be too worried about this — we’re fairly robust creatures.

Now in the course of doing this, John Smythies came out to Saskatchewan for about a year. Our paper had been published then. It wasn’t quite a lead balloon, but at that time it wasn’t much more than that.

In the course of writing our initial paper, “Schizophrenia: A New Approach,” he had been writing a paper on — I think it was called “A Comparison of Psychological Medicine in the 20th Century with General Medicine in the 18th Century.” What he pointed out was that in the 18th century there existed schools of medicine which by the 20th century had disappeared from all branches of medicine with the exception of psychiatry. He suggested that the time had come to give up this anachronism. This was published in a philosophical Journal — The Hibbet Journal — and a copy of this reached Aldous Huxley in Los Angeles. Aldous read this and sent us a very nice letter which reached us in the middle of’the Saskatchewan winter, enclosing a copy of his most recent book.

It wasn’t the Mind Journal, but the Hibbet?

The Hibbet Journal, which has sort of gone out of business, and I think it is probably associated with Mind now. Anyway, Huxley sent us a copy of his most recent book, which I think was The Devils of Loudon, and invited us, if we should be in Los Angeles, to go and see him.

Now at that time — you remember, this was 1953, thirty years ago — and the other thing you’ve got to remember is that we were Englishmen. The idea — we looked at the map and it seemed an incredible distance, Saskatchewan, anyway, is a long distance, and the planes were very slow, and — I don’t know about John — but I had never flown at that time commercially. I had flown a tiny bit in military planes in the Navy — I didn’t want to repeat that. They were too dangerous.

At any rate, we were very nice. John said, “If we do go down there, we must go and see him.” But it was a very big “If.” Also, we were at that time very poor. So that the idea of going down there seemed incredible.

But an ‘extraordinary thing happened. Within about six weeks from that letter, I was actually asked to go to the American Psychiatric Association — of which I was not a member — to go officially for the province of Saskatchewan, the reason not being that they especially wanted to educate me more, but because great political difficulties had arisen.

I was the Clinical Director of a hospital in which the superintendent was a very old and odd gentleman who found it very threatening — the idea that his really snakepit hospital was going to be cleared up. It had to be cleared up. It had almost 2,000 people in it. It was in the most disgraceful state. It had underground walls with stalagmitic and stalactitic feces. I mean, it was the real thing. It stank. It had people lying on the floor.

In fact, the pictures that we took of it in 1957 — when they came down to the APA, and when we got the Silver Plaque Award for the most improved hospital — when they went through the United States Customs, which they had to do, they were held up as “obscene documents.” They had to be specially released, and these were not the worst!

So anyway, my old predecessor thought this was a great threat to himself. There was, in fact, no idea that it would be a threat to him. It was perfectly clear what the idea was. He was to stay on as a kind of figurehead, and we would get the place cleaned up. But he didn’t like that. Cleaning up meant doing a great many things differently. By implication, it did mean that what changed.

There was an interesting thing about this — it was the only mental hospital that was officially on the prairies. All the others were, strangely enough, on parkland. So this was the only prairie hospital — certainly in Canada, I don’t know about the United States.

So anyway it became necessary — it didn’t work this way, but the idea was that they would put the heat on him while I was away, and that I would not be identified with this. Anyhow, they thought that I had had a somewhat wearisome time. And so, in the depths of the Saskatchewan winter, I wrote off to Aldous to say that John couldn’t come but I would be delighted for his invitation to come and see him when I was staying in Los Angeles.

I got this letter back suggesting that I stay with the Huxleys. Maria later told me what happened. She said that Aldous came down, read this thing, and said, “Why don’t we ask him to stay?” And she said, “Who’s him?” He said, “This fellow Osmond.” She said, “Well, who is he?” “Oh,” he said, “he comes from Canada and he’s interested in mescaline.”

Maria said, “Well, you know, Aldous, we never have people to stay. We don’t even have Julian (Aldous’ brother) to stay, we put him up at the White Tower.” Aldous said, “Well, we can always be out.”

I got this very strange letter inviting me there. I showed this to my wife, and I said, “You know, really, this isn’t my League. I think I better go there and just go visit him.” She said, “If you do that, you’ll never forgive yourself.” And so I took her advice, and I wrote a rather equivocal letter, saying that I, of course, would, in the course of my duties, have to spend much time at the APA.

Well, the APA turned out to be, of course — as these great meetings are usually — considerably boring. I arrived in Los Angeles on, I think, it must have been about the 5th of May after having done this great journey down through Vancouver in a prop plane, you know, at 14,000 ft. A beautiful journey, much more beautiful than jets. I was looking out over the Rockies in a jet yesterday it really isn’t the same thing at all. In a prop plane, you get a marvelous view.

So anyway, I drove to — I think it was 740- something Kings Road — and went along full of apprehensions. Aldous came out of the shadows, looking like one of Blake’s great figures. Maria was there, like a sort of remarkable, little bird.

I felt that it would be very, very difficult to talk to Aldous — that his conversation would be stratospheric. It turned out that it was very easy to talk to him. He was extremely amiable and friendly, and when she said that evening, “I know you and Aldous are going to get on very well together,” I still wasn’t quite sure why. She said, “You’re both Englishmen you’re bound to understand each other.” I thought, Really, this is the most extraordinary idea!

But Maria believed that all Englishmen were extremely odd and that they automatically understood each other. There was something to it, though. In her strange, intuitive way, she had picked up something that she couldn’t possibly have known. This was that we were born within about two miles of each other.

We had a lot of geographical things in common — and this is very important for people of our temperament. We actually had a lot of commonality. We had a good deal of cultural commonality — of course, I wasn’t nearly as well educated as he was — and we had a lot of common interests. And so, in fact, quite right.

I took along Aldous to the APA meeting, and he sat there during the academic lecture crossing himself every time they mentioned Freud. But no one was looking. I was able to note that most of the people seemed to be of closed eyes in a pious way. The lecture was extremely boring, so it was possible they were having a slight snooze after the exertions of the day before.

At these medical conventions, as you know, they always believe there should be a great deal of entertainment, and so consequently, many of the people, I would say, drink a bit too much and really are quite worn out. This combination of too many people, perhaps for some too much liquor and certainly too much food, makes people rather sodden — and far too much information.

But, at any rate, then the dread time arose of giving Aldous this mescaline which I had brought down. I didn’t know the laws of California which turned out — luckily, I think now that there’s a certain seven-year thing, isn’t there? A —

Statute of limitation?

So I can be quite open about it. But that was simply ignorance. I would probably not have broken the law deliberately, but I don’t know. Because the stakes were high. I thought there would be no better way to see what this stuff did — and there are very few accounts, apart from Havelock Ellis, Weir Mitchell and a few others. And some of them are very good ones, actually.

Anyway, I gave — there was this morning, which I have described I think fairly accurately, of my apprehensions and concern, and popping the stuff in and Aldous taking it, and then out of this came The Doors of Perception.

In the “letter book,” I described this strange thing of the lady next door, Betty, who was of the impression Aldous was wearing blue jeans. I luckily have this picture. As you can see — I now have had it blown up, and I can see perfectly well he’s wearing the gray flannel bags that English gentlemen of Aldous’ age wore informally. I think I’ve seen Aldous once in blue jeans, when we went out in the desert. But this was seen as very unusual. Aldous normally wore gray flannel trousers, which Englishmen thought was their informal dress.

Anyway, after this Aldous promised to write this report — which became The Doors of Perception. I went back to Saskatchewan, where the political battle went on in a dismal way, but it was eventually resolved. And, of course, for much of this time I was mostly involved in getting the hospital into shape.

But, however, also because of my work with Abram Hoffer and because of his great interest in this, and our later work and interest in the amenochromes, adrenochrome and LSD, we decided that we would really — out of, from our point of view, keeping ourselves sane —

While getting a hospital together is a full-time job in a way, a great deal of the full-time job is getting people to start doing things. And during that time — I later became the director of that hospital, the superintendant — he actually does not lave a great deal to do, if he’s got the moves right.

It’s like a general in the battle. If you’re a good general, you don’t fuss around. You do what Montgomery did — You go to bed on the day the battle begins, and sleep until, as he said, “The soldiers brought the battle back to me.”

Now that — of course, I was too inexperienced then to understand that this is the heartland of command. You get other people to do their duty and you encourage them and support them. You don’t go and breathe down their necks all the time. Otherwise, rou get an organization which will go to bits as soon as you go away.

With my naval experience absolutely delightful but alcoholic captain, and an absolutely marvelous first lieutenant, and they put these things into practice. They ran a marvelous ship, a taut ship — but it was a ship in which people were happy. It’s difficult, you know, in a. destroyer in mid-Atlantic, under dreadful conditions, over-crowded, with young and frightened men on board, inexperienced, । to have them happy. But this genius knew how to do it.

I therefore learnt by watching him that the essential thing there was their morale. That would be quite contrary to many things — even though Karl Henninger came up and said these ludicrous things, like that, “The first thing you must do is get rid of all your present staff.” It’s ludicrous. You can’t do this, I say. With a defeated army, the first thing you do is I to get rid of the army — and then you haven’t got anyone.

The first thing you do is to raise their morale. And our experiments helped to do that. To begin with, as my old friend Bob Summer, who is up at Davis, has pointed out, there’s a great deal of evidence that undertaking research anywhere raises morale — because, of course, it makes you think that you’re going to do something. Or something new may develop.

So during this time we carried out certain studies — some with LSD, some with mescaline, and some with our amenochromes which we found were dangerous things. And then — initially actually with the mescaline, having read this account of Bill W, and William James about the effect of these — what later came to be called psychedelic experiences on alcoholics.

We didn’t actually do it this way. The real way this happened was that Abe and I were traveling from Ottowa one night, where we were on our way of getting money, and we were wearied and we had been talking about schizophrenia so long that even that wonderful topic was becoming tedious, and we turned our mind to another of our great headaches — which was alcoholism.

We were thinking about this, and it suddenly struck us that the accounts show very clearly — from Bill W.’s, and many, many others — that the critical thing is to get d.t.*s. and then to have an unusual experience. And we said, “Why couldn’t you do that a bit early?” And if you got that ahead of time, the person might be in better shape, and they would then upset themselves and do exactly what they would have done normally but they would do it before they were dead, which was a good idea. And so, anyway, we set up this.

I got a lady who had been drinking a great deal, gave her some mescaline and she, indeed, did have at first a sort of delirium-like experience, but then she had an experience that did a great deal to resolving many of her problems. And so we thought perhaps that we had set about it the wrong way. Abe mostly used LSD. I had some mescaline, but later I went back to LSD, We, in fact, did large numbers of people. I would say over a hundred of them.

It’s perfectly true that we did not have a comparison. We believed — and I think we’re still right — there isn’t a comparison for the psychedelic experience. It just doesn’t work. And also we were then interested in seeing the phenomenon.

This lady, who I saw from time to time — her recovery wasn’t entirely without incidence. But, in fact, we followed it up for some years — something like four or five years — a lady who had been drinking herself to death who stopped drinking. I hope she went on doing it after this.

But the obvious thing, actually, of course, when you think of it, would be to repeat this experience. That is, perhaps once every six months. It would be extremely economical and extremely sensible. Because people need to be reminded of these things. The other thing is that with each of these, one would hope that the person would get a better understanding of themselves and their affairs, and as they stopped drinking more, this would be easier for them.

With all these things, they also, of course, made us very much interested in the effect of this experience as a therapeutic thing. And, of course, we had many people.

At this time, Al Hubbard had, I think, read The Doors of Perception. I don’t know whether he had gone down to see Aldous then, but in 1954, when I came back from my second visit to see Aldous and when I gave Gerald Heard and Aldous mescaline, Gerald had a very, very interesting experience. I got a very good picture of Aldous then too.

I met Al in the Vancouver Yacht Club in B.C. He had met one of our nurses, who had gone out there, and he had heard about this. And he, with his inimitable way, had initially gotten hold of some mescaline. And he started trying it out on various people with his usual boldness. Also, he felt that this had special interest — as you know, he had many spiritual interests, and he felt that this would be very useful to this.

And I must say, I found him a most puzzling and interesting chap. Indeed, he remains so to this day. A kind of demiurgic figure, you know, a sort of mythical figure almost. And he, with his extraordinary background, which is always sort of — I’m never sure how much of it is so or what. Was he a rum runner? Did he work for the CIA? What about this extraordinary business of the boat? You know, the boat that he powered with uranium? There were articles about it in the press.

You don’t know the story? Well, in Seattle in about 1920-something, Al put a boat around that was said to be powered with radium. A direct conversion. That’s what articles said. No one has found out how it was done.

I urged Al to do this again. For reasons that are quite unclear to me — was it that he was an unbelievably clever con man then, or was it, as he says, that he didn’t feel the world was ripe for it? I don’t know. But what happened was that he had borrowed some uranium, he put it in whatever thing this was, he converted it directly to energy — that is what the people believed and wrote — and the boat rode around Seattle harbor. It’s all there. Very strange.

Al and I got to know each other very well. We had taken LSD together on occasions, and began to develop this technique of trying, as it were, to move into each other’s worlds. It was in this way that I became very, very interested in the idea of umwelt.

Now, Aldous had become — well, as you know, always felt temperament was enormously important. And in 1955, when he got me a thousand dollars to go and see Jung — which was a lot of money at that time — I took with me a book by William Sheldon, the father of somatotyping that he had given me to take to Jung. He was a pupil of Jung’s, and a great admirer of Jung’s.

I took this book to Jung, and Jung was very pleased with it. It had an apology, saying that he was sorry that he hadn’t devoted more of his time to the psychological things that he thought were so very important. Jung said, “Why, we must give the body its due.” He said, “Didn’t your Shakespeare say, ‘Yon Casius has a lean and hungry look. He thinks too much. Such men are dangerous. Let me have men around me that are fat, sleek-headed men, and such as sleep anights.’ “?

And he said, “Of course we have to give the body its due,” Now, of course, I didn’t go to see Jung out of an interest in typology, or in general Jungian interests. I was interested in schizophrenia. We had a most delightful time, most of the time devoted to schizophrenic interests. He was very interested in the biological basis of it. He had written The Psychology of Dementia Praecox in 1906. Our work lies very much close along his.

In 1906, De Lombargia had just discovered the effects of adrenaline on nerves, and on animals, so that there was tremendous personal interest. He very much liked the idea that adrenaline could turn into these things that he called “Toxin X” so many years ago. As he told me, he said, “Do you think I would have wasted my life with all this if the chemists had anything to tell us?” He remained deeply interested in this extraordinary illness.

In the course of this visit, he did touch upon this matter of temperament, saying how these were matters of temperament. Now Jung — his relationship to his own great book, Psychological Types, and his relationship to temperament, remained very peculiar. He wrote these books — well, he wrote Psychological Types, apparently, to try and define the breakup of the relationship between him and Freud. But the book comes to an end without telling you anything about this, except that he felt — we don’t really know what he felt, because no one ever really cross-examined him on this.

He felt, as he would say sometimes, that the Freudian psychology was really an extroverted psychology, and his was an introverted one. However, since Jung himself was highly extroverted, and Freud was quite introverted, this doesn’t seem to make a great deal of sense. I have read accounts — and I’ve met Jung myself — I remember I once asked my old friend John Smythies, “Do you feel that Jung was very Introverted?” and he roared with laughter. He was one of the most outgoing of men. And therefore, obviously something had gone wrong.

One of the things that most people interested in temperament have never thought clearly about is that it’s very likely that you will make serious mistakes in estimating your own temperament. For a variety of reasons. You might — Jung for some reason or another, perhaps simply because he was highly extroverted, “tremendously was fascinated by introversion, and romanticized this.

My own sort of observation on introversion is that it is fine so long as you don’t have too much of it. And then it can be a tremendous burden, in the same way as with all these things. They’re fine if you know how to use them, and if you know what they are. Now if, for one reason or other, you get the belief — particularly if you’re a highly extroverted person and feel rather introverted — then you’re bound to … or the other way around. If you’re an extroverted person brought up in an extroverted family, you have to take on their values.

Of course, Jung had made a much more complex thing of this. But due to the fact that this central theme, as to what his temperament was and what the conflict was with Freud — since this was distorted by this error of judgment, the whole thing remained rather odd.

Added to this, Jung became a kind of semi-willing guru for the Jungians. As Aldous said, Krishnamurti told him — he said, “Never let yourself be made into a guru.” Krishnamurdi, as ; you know, is one of the few retired gurus. He left being a guru at thirty, which was extremely sensible. But he said, “The thing about being a guru is that it’s so bad for the guru. It is liable to destroy him.”

That is, you get pious people who like to have gurus, and they, in fact, turn the chap into an idol. And then he truly does become that, and then the necessity of thinking about these things. Any odd remark he makes, like with Gurdjieff — any old nonsense Gurdjieff made was written down by someone and it was then announced to be, you know, enormous wisdom.

Well, the fact is that it is sort of a crossword puzzle, or an acrostic, or — the most banal of proverbs can be made into wisdom if you think long enough about it, if you’re clever enough and devoted enough. It’s like haiku. Some of the haiku are nonsense, some are brilliant. Some are both.

But the fact is that this is very bad for people — to be placed in the position that their idle remarks are liable to be seen as — Of course, the other point about it is that some of people’s idle remarks are much better than their thought-out remarks. This is true. But the real thing is that it’s bad for the person.

This, of course, is one of the most charming things about Aldous — is that he refused to be a guru. Now he would retreat. If he was bored — I’ve seen him bored at times — he would sort of remove himself, you know, and he would be somewhere else. But he never became a guru. He wouldn’t do that, and that was because he thought of Krishnamurti’s excellent advice.

And also, Gerald Heard came along with this. Gerald Heard told him, and he told me too, that one of the things that religious gurus do — and, of course, not all gurus are religious — is that they burn themselves out in attempting to inspire people beyond the limits of human endurance. The Wolsleys did this. All of them do it, and after they do this they stop being inspiring.

And, of course, for very good reasons. The fact is that if their message is any good, it gets across and very soon becomes converted from being a new and extraordinary truth into being a useful working moral rule.

And then, as my old friend Tom Patterson — Tom and I have groups — participatory relationships — this thing called “typo-methexics.” This tells you in any particular group of people what role you’re likely to fill best. It also tells you what types of groups are probably not viable

That is, highly homogeneous groups are in a way certainly they’re non-viable for innovation, and change.

You can make highly homogeneous groups in which none of the people want to change. You can make highly homogeneous groups which don’t last long in which all the people want to change in their own direction. So these things are all sort of developed from here.

Well, anyway, I was naturally very interested after meeting Jung in these temperament things, but there wasn’t at that time great deal we could do about it. We were using the idea of what on Uxe calls umwelt, but again with our schizophrenics. And be and I developed this little HOD test, which is a way of getting quick window into the world of the ill person.

Now I don’t think we would have done that at all, if we had not both taken mescaline, LSD, the amenochromes and these sort of things. We knew very well that they could tell you about this world, given a bit of help. That thing that you quote in the Encyclopedia about Norma McDonald (a recovered schizophrenic, who found that she “could talk to normal people who had had the experience of taking mescaline or lysergic acid, and they would accept the things I told them about my adventures in mind without asking stupid questions or withdrawing into a safe, smug world of disbelief — she’s an extremely able and charming lady, and this was a tremendous help to us. The fact that she found this helpful, and we now know this is so … .

And so with these things from psychedelics, it’s one of the ways of making sense of them. And then, of course, with our HOD test this eventually led to Bernie Aaronson’s work with hypnosis, which is a more structured way so that you can look at the thing and see it in depth.

With LSD, we must hope one day that something like ololiuqui or LSD amide or something will allow one to make single focuses, because for scientific study that’s what you need. LSD itself is not probably meant for this, and anyhow you would have to be so highly trained to focus it properly. You can do this — I know this and we’ve done numbers of things with it, but it’s not, I don’t think it’s tremendously for everyday use, You’ve got to have trained specialists to do this, who we were never able to — This, of course, was one of the objects of the exercise — was to do this. In 1953. you remember, there’s this letter from Aldous to the Ford Foundation, in which we were going to go around to these eminent people and from there produce proper ways of studying. Tim later came to the conclusion, I think a bit too late, that what we needed was kind of ashrams or something in which one would make sustained study. But, unfortunately, he had also before that thought of a guerrilla warfare to sort of stir up the establishment. And that, unfortunately, came to coincide with the war in Vietnam. These two got tremendously mixed up.

What we had hoped — we were going to select some sixty eminent people. In your thing Psychedelics Encyclopedia, 1983 p. 25), Tim discusses that he came to the conclusion that this elitist approach was the correct one. Which, of course, shows what a nice chap he is, because I think that actually goes quite against his temperament. Because Timothy, as an “Oceanic,” you see — these people are always interested in totality. And that is not, I think, our bias.

Our error is the other error — it is the Coriolanus error. That is, we believe in elites. In a democracy, maybe you don’t talk about it too much. But the fact is that both these things are true. There are occasions when elitism is necessary, and there are occasions when the holistic, oceanic approach is necessary. . .