“It is paramount to keep in mind that language must meet the strictest requirements in the determination and communication of terms. But the formal aspect, the conceptual and logical, must never be pushed to the realm where technical mists cloud and too often dictate the final interpretation”

NAGARJUNA, A Translation of his Mulamadhyamakakarika, Kenneth K. Inada

***

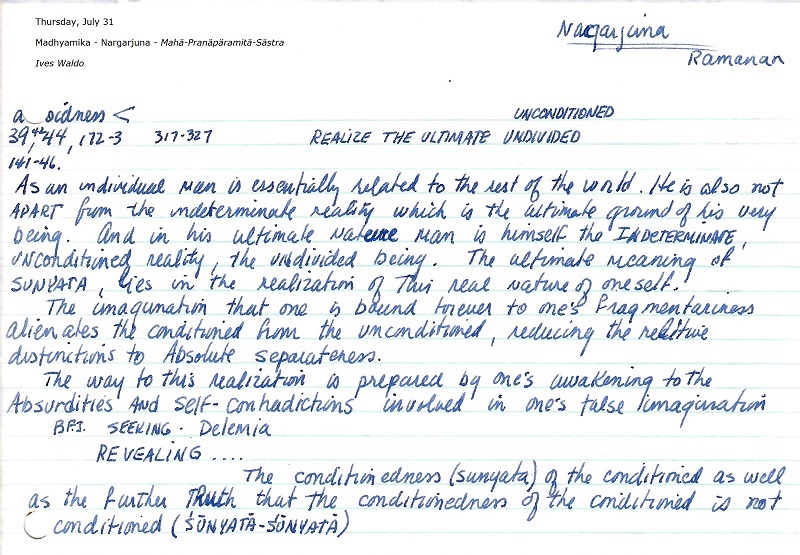

Notes from Naropa University

Ed Reither, 1975

pp. 171-173

CHAPTER VII

CRITICISM OF CATEGORIES

Section I

THE MUNDANE AND THE ULTIMATE TRUTH

The disclosing of the mundane and the ultimate truth: To cut at its root the tendency to cling to the specific as ultimate is the deepest truth of the denial of self which the Buddha taught. It is a denial not of the self itself but of the falsely imagined self-hood in regard to the body-mind complex.

The basic meaning of self is underivedness, unconditionedness. The self-being (svabhava) is the independent, unconditioned being which does not depend on anything to come into existence. Even the “coming into existence” is not relevant in regard to it, for it never goes out of existence. That which was not existent before, is existent now, and will cease to be later is not the self-being. But arising and perishing are the very nature of the elements that constitute the body-mind complex. So the Buddha declared that the entities that are subject to arising and perishing are not fit to be considered as the self, for they are devoid of the nature of self, viz., self-being. It is this imagination of selfbeing or absoluteness in regard to the conditioned and contingent that is the root of error and suffering. It is this that the Buddha exhorts everyone to dispel. In its general form this is the error of misplaced absoluteness.

We have already seen that for Nagaijuna the Sarvastivadins’ doctrine of elements becomes an important and glaring instance o f this basic error. It is the categories of the Sarvastivadins that become the primary object of criticism in his works. He points out that the Sarvastivadins cling at every step; they seize the relative as self-being and commit the very error against which the Buddha warned all His disciples, viz., the extreme of eternalism.

The extreme of negativism takes a minor place in the works of Nagaijuna, although its mention and criticism become necessary for him for at least two reasons: I) Criticism of categories culminating in the revelation of their non-substantiality may itself tend in the case of one who follows the way of sunyata but with a clinging mind to end in the extreme of negativism, denying even the relative being of things and thus denying the very possibility of causal continuity II) Again, the clinging in mind who are not the followers of the way of sunyata might easily tend to mistake it as a negativism that ends in an utter blank, a complete nothing. While the latter is the false imagination that criticism puts an end to things themselves, making them non-existent, the former is the error of imagining that the

that the non-being of things indicated by their passing away is total. The latter mistakes the nature of criticism and the former, the nature of the course of things. Both these are really forms of the same kind of clinging, viz., the clinging to negation or nonbeing. The way out of these lies in realizing relativity as the essential nature of things. Criticism or critical examination of the categories is a means to lay bare this true nature by putting an end to the false imagination of absoluteness in regard to the relative. Further, the very relativity of “is” and “is not,” being and non-being, removes the notion of an absolute cessation of things. What is called relative non-being is only difference or change, which is not unconditioned.

It must be noted that the charge of negativism brought against the Madhyamika is occasioned partly by the circumstance that he does not always make the distinction clear between the rejection of unconditionedness that reveals conditioned becoming as the mundane truth and the rejection o f the ultimacy o f the conditionedness o f the conditioned that reveals the unconditioned, the undivided being as the ultimate reality. The primary meaning of sunyata is devoidness which is a direct reference to the truth of things, mundane and ultimate; but it refers also to the method (criticism) by which sunyata as truth is brought to light, viz., by rejecting the imagination of ultimacy and absoluteness in regard to what is only relative and non-ultimate. Sunyata as the mundane truth is relativity and conditioned becoming; this is brought to light by rejecting the supposed ultimacy and absoluteness of particular entities and specific concepts and conceptual systems, sunyata as the ultimate truth is the unconditioned, undivided being which is the ultimate nature of the conditioned and the contingent; this is brought to light, again, by rejecting through criticism the imagination of the ultimacy of the conditionedness of the conditioned and consequently, of the division between the conditioned and the unconditioned. The first kind of criticism and the truth it brings to light are just called sunyata, whereas the second kind is, strictly speakings sunyata of sunyata (sunyata-sunyata) . But usually both these kinds are bracketed within sunyata without always making the distinction explicit. This is no doubt a source of confusion for all those to whom the distinction is not clear.

And the charge that the Madhyamika contradicts experience and lands in a blank draws its roots from here. However, this distinction is made explicit by him when he is challenged with this charge. He will then point out that far from disavowing or even contradicting the mundane truth, sunyata is the only way in which the truth of things can be brought to light, and the cultivation of wayfaring be made possible. Between the denial of absoluteness in the case of mundane things and the realization of the ultimate truth as the unconditioned reality, the undivided being, there is the most important intermediary, viz.’, the recognition o f the mundane truth as conditioned origination. It is here that all mundane activities belong. The primary purpose of criticism is to set free the thirst for the real from its moorings in abstractions, its illusions about the nature of things, and to direct it to the truly unconditioned.