The Dicts and Sayings of the Philosophers

“A Taste”

Beezone

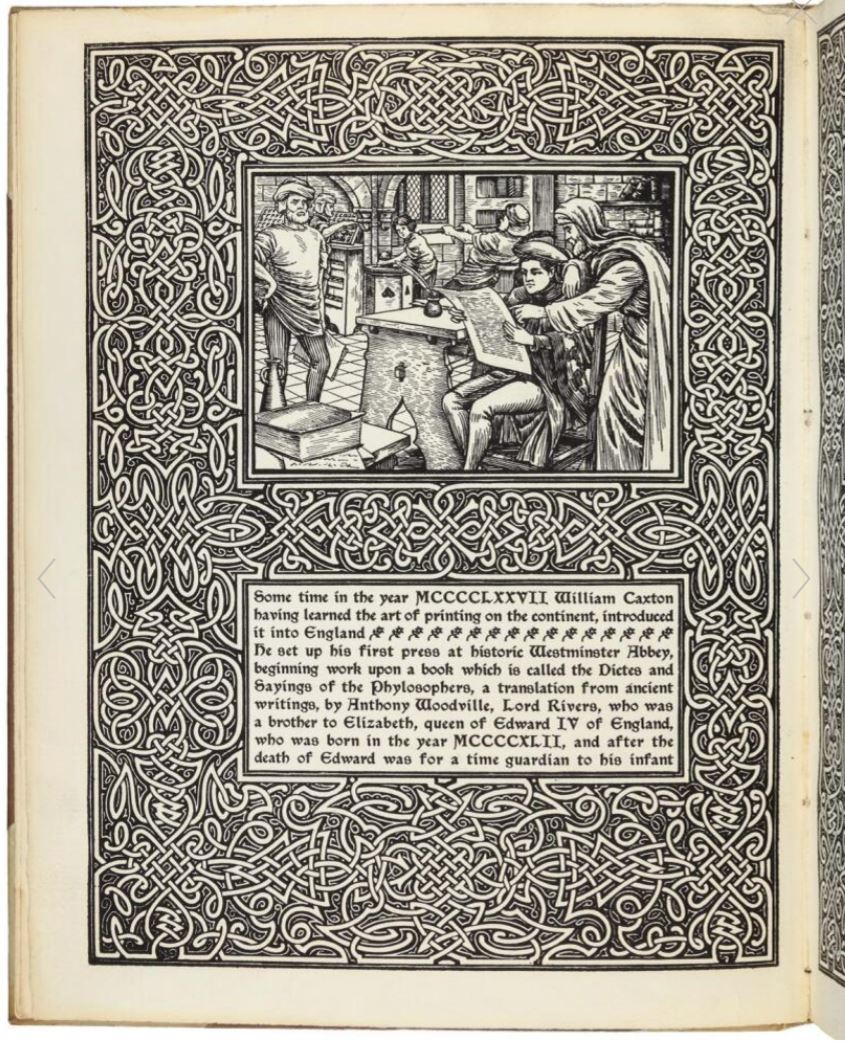

The Dicts and Sayings of the Philosophers is a medieval collection of wisdom literature attributed to Mubashshir ibn Fātik, an 11th-century Egyptian scholar and philosopher. His work, titled Mukhtar al-ḥikam wa-maḥasin al-kalim (“Selected Maxims and Finest Sayings”), compiled ethical and moral teachings from ancient philosophers such as Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato. This text emerged within a medieval Islamic world deeply engaged with philosophy, especially the works of the ancient Greeks; in fact, the Arabic term falsafa (“philosophy”) is a direct transliteration of the Greek philosophia. As Michael Marmura points out, “medieval Islamic philosophy, as we know it, was a direct result of the translations of Greek philosophy and science into Arabic. It is rooted in Greek philosophy.” While Plato’s works reached Muslim thinkers primarily through summaries and paraphrases (such as Galen’s Synopsis of the Platonic Dialogues), Aristotle’s work was widely available and highly esteemed—he was even referred to as “the first teacher.”

In translating Ibn Fātik’s text into French, medieval scholars modified and expanded the original with commentary to make it more accessible and engaging for a European audience. This French version eventually served as the source for Earl Rivers’s English translation, which introduced these philosophical teachings to English-speaking readers. Rivers’s translation provided an important cultural bridge between Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, marking a significant moment in the Renaissance rediscovery and integration of ancient wisdom. The complex relationship between Greek-based falsafa and Islamic theology—where philosophy was seen as foreign in a world deeply shaped by the Qur’an and Islamic law, as Thérèse-Anne Druart explains—only enriched the layered wisdom that found its way into European thought through works like The Dicts and Sayings of the Philosophers.

TEXT

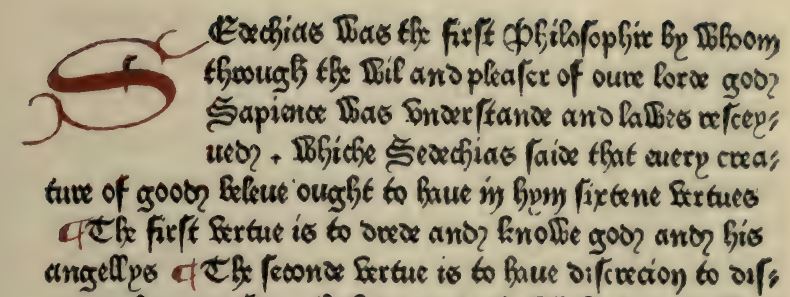

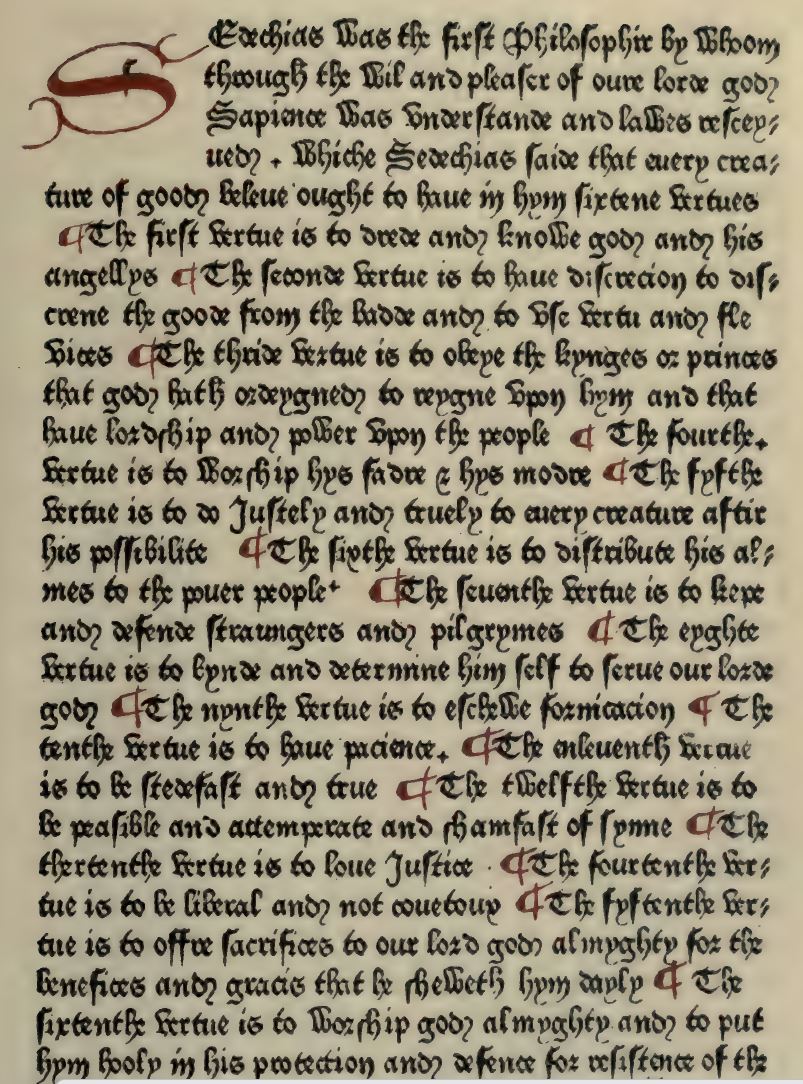

“Zedechye was the first philosopher who, by the will of God, first received the law and understood wisdom. And this same Zedechye says that every person of good faith should possess sixteen virtues. The first is to know God and His angels. The second is to have discernment between good and evil—doing the good and avoiding the evil. The third is to obey kings and princes whom God has placed on earth to govern and rule, and to have power over the people. The fourth is to honor one’s father and mother. The fifth is to do good to everyone according to one’s ability. The sixth is to give alms to the poor. The seventh is to protect and defend strangers and pilgrims. The eighth is to dedicate oneself entirely to the service of God. The ninth is to avoid fornication. The tenth is to be patient. The eleventh is to be truthful. The twelfth is to be just. The thirteenth is to be generous. The fourteenth is to offer sacrifices to God for the great benefits received from Him each day. The fifteenth is to thank God and entrust oneself fully to His care for the different fortunes that continually arise in this world. The sixteenth is to be modest, peaceful, and temperate.

- To know God and His angels.

- To have discernment between good and evil—doing the good and avoiding the evil.

- To obey kings and princes whom God has placed on earth to govern and rule, and to have power over the people.

- To honor one’s father and mother.

- To do good to everyone according to one’s ability.

- To give alms to the poor.

- To protect and defend strangers and pilgrims.

- To dedicate oneself entirely to the service of God.

- To avoid fornication.

- To be patient.

- To be truthful.

- To be just.

- To be generous.

- To offer sacrifices to God for the great benefits received from Him each day.

- To thank God and entrust oneself fully to His care for the different fortunes that continually arise in this world.

- To be modest, peaceful, and temperate.

And he says that just as it is proper for people to be subject and obedient to the king’s majesty, so too it is fitting for a king to diligently understand the governance of his realm, putting this duty above his own interests, for the king is to his people as the soul is to the body. He also says that when a king tries to accumulate treasure through extortion or other improper means, he should know that it is wrong, for such treasure cannot be gathered except by plundering his realm. And he says that if a king is slow to investigate the actions of the great men among his people and his enemies, he will not remain secure in his kingdom for even one day. And he says: ‘Oh,’ he says, ‘the people are most fortunate when there is a king of good discernment, wise in counsel and knowledgeable in sciences. And the people suffer greatly when any of these qualities are lacking in a king.’”

Old English

Zedechye was the first philisophre, which, by the will of God, lawe was first resceived and wisdam undirstanden. And the seide Zedechie seith that every man that is of good beleve shulde have in himself sixtene vertues. The first is to knowe God and His aungellis. The secunde is to have discrecioun of good and evel – of the good for to do it and of the evel for to leve it. The thridde is for to obeye to kinges and princes that God hath sette on erthe for to governe and reule and have puis saunce over the people. The fourth is for to honoure fader and moder. The fyveth is to do every man good aftir his power. The sixte is for to geve almes to the poore people. The seventh is to kepe and defende straungiers and pilgrymes. The eighth is to abaundon himself entierly to the service of God. The ninth is for to eschewe fornycacioun. The tenth is to have pacience. The eleventh is to be true. The twelfth is to be just. The thriteneth is to be liberall. The fourteneth is to offre God His sac refices for the grete benefetis that he resceiveth of Him every daye. The fifteneth is to thanke God and put himself holly unto His keping for the divers fortunes that contynuelly comen in this worlde. The sixteneth is to be shamefast, peasible, and wele attempred. And seithe that as it apperteyneth to the people to be subjecte and obeissaunt to the kinges magesté, in lyke wyse it longeth to a kinge to undirstande diligently the governaunce of his roialme and mor [fol. 1v] thanne to his owen propre, for in lyke wyse is the kinge with his peple as the soulle is with the body.

Read more