Title: 80 Years of Silence: Examining Restrictions in the Harvard Archives and the Need for Transparent Appeal Processes

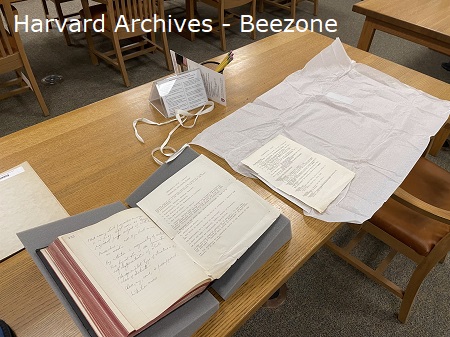

This essay emerged from my efforts to obtain materials from the Harvard University Archives while researching for my course, The Harvard Psilocybin Project, 1960-1963. — Ed Reither

Introduction

In one of the most storied archives of American higher education, Harvard University’s archival restrictions on sensitive materials are beginning to raise serious questions about transparency, academic freedom, and institutional accountability. For decades, researchers have encountered significant barriers when attempting to access key archival materials marked with “pink cards,” indicating that they are restricted from public access—often for up to 80 years. These restrictions, implemented at the discretion of the Harvard Corporation, have prevented scholars from fully exploring important aspects of the university’s history, especially when it comes to controversial topics and notable figures.

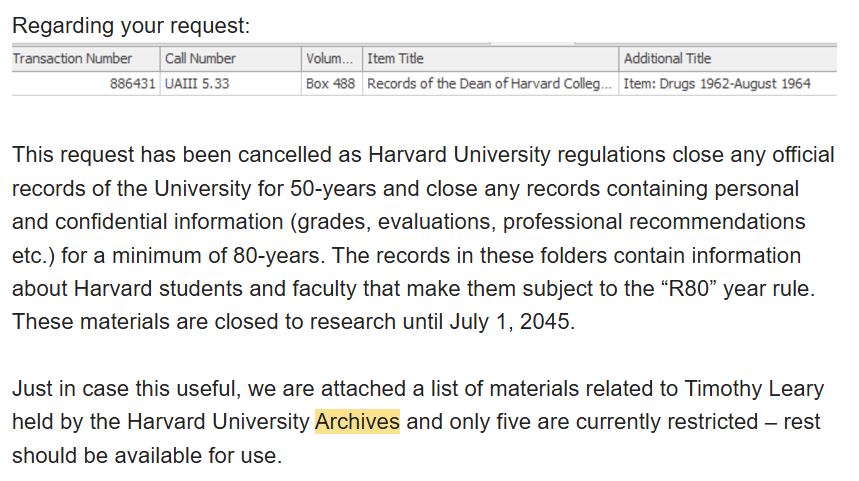

One such instance involves the case of Richard Alpert’s 1963 firing, restricted within then-president Nathan Pusey’s papers. Despite attempts to request access, the current system allowed for no transparent process or formal means of appeal, leaving critical inquiries about Harvard’s past shrouded in secrecy. In a time when many academic institutions are striving for openness, Harvard’s policy raises questions about the ethical responsibilities of academic archives in relation to public history and institutional self-examination.

The Issue with 80-Year Restrictions

Harvard’s policy of restricting access to certain documents for up to 80 years is not without precedent, as many archives enforce restrictions to protect sensitive personal information. However, at Harvard, this restriction has been applied broadly to shield not just personal records but also institutional and administrative records that reflect broader historical issues and decisions. While some level of confidentiality is reasonable, this 80-year standard, which appears to apply indiscriminately, has created a backlog of inaccessible materials that could otherwise contribute significantly to the study of American educational history, social movements, and institutional responses to major events.

The restrictive handling of these materials impacts researchers directly. Without access to critical documents, scholars are unable to provide nuanced historical narratives or challenge established interpretations. The firing of Richard Alpert, for instance, is a pivotal moment in Harvard’s history related to academic freedom, drug policy, and shifts in intellectual currents during the 1960s. The imposed restriction, however, effectively erases this historical episode from broader public knowledge for decades, despite significant public interest.

The Absence of a Formal Appeal Process

Attempts to access restricted materials within Harvard Archives often meet with an opaque and dismissive response. Researchers may contact archivists to request access, but the archivists ultimately defer to administrative decisions that seldom offer pathways for appeal or transparency. When seeking access to the Pusey files related to Alpert’s dismissal, researchers have had to navigate an informal network of approvals, including discussions with university officials, only to receive outright denials without further explanation from Dean Khurana.

The absence of a formal appeal process for restricted materials denies researchers a chance to make a compelling case based on academic or historical merit. This lack of procedural recourse not only stifles scholarship but also points to a larger institutional culture that selectively curates its historical record, preserving a narrative that may be biased by omission.

Comparisons and Recent Developments

The case of the “Secret Court of 1920,” which saw the expulsion of students suspected of homosexual behavior, provides a relevant comparison. The incident remained hidden for decades, with related documents restricted until the early 2000s. Public outcry and sustained advocacy eventually led to a review by the Harvard Corporation, allowing researchers access under specific conditions. This case illustrates that Harvard has the capacity for flexibility in granting access but only on rare occasions, often requiring significant public pressure. By not establishing a structured process for appeals, Harvard relies on case-by-case decisions that can seem arbitrary, privileging some research requests over others without transparency.

Recommendations for Procedural Reform

“The Director of the University Library, or his/her representative, usually the Curator of the University Archives, to authorize the use of University records more than fifty years old (or records concerning individuals which shall be more than eighty years old, or the individual being alive, after his/her decease, whichever is later), provided they are not fragile original records that might be damaged by use, in which cases copies will be provided.” See: (https://library.harvard.

Harvard could improve access to restricted archival materials by implementing a more transparent and formal appeals process. Such a process might include:

-

A Review Board: Establishing an independent archival review board, including scholars, archivists, and community representatives, could evaluate requests based on scholarly merit and historical significance.

-

Defined Appeal Guidelines: Clear guidelines for appeal eligibility and specific criteria for reviewing restrictions would give researchers a transparent understanding of the process and conditions under which access might be granted.

-

Limited Access Protocols: In cases where sensitive information is a legitimate concern, Harvard could implement partial-access or limited-viewing protocols, allowing researchers to examine records with confidentiality agreements rather than entirely barring access.

Conclusion

The restrictive practices of the Harvard Archives, without formal procedures for appeal, reveal a gap between the university’s legacy of intellectual freedom and its archival policies. An 80-year restriction on materials limits our collective understanding of pivotal events and inhibits academic freedom, effectively censoring history. To truly serve as an institution of learning, Harvard must confront its own history with the transparency it demands of others, adopting a system that respects both individual privacy and the integrity of historical inquiry.