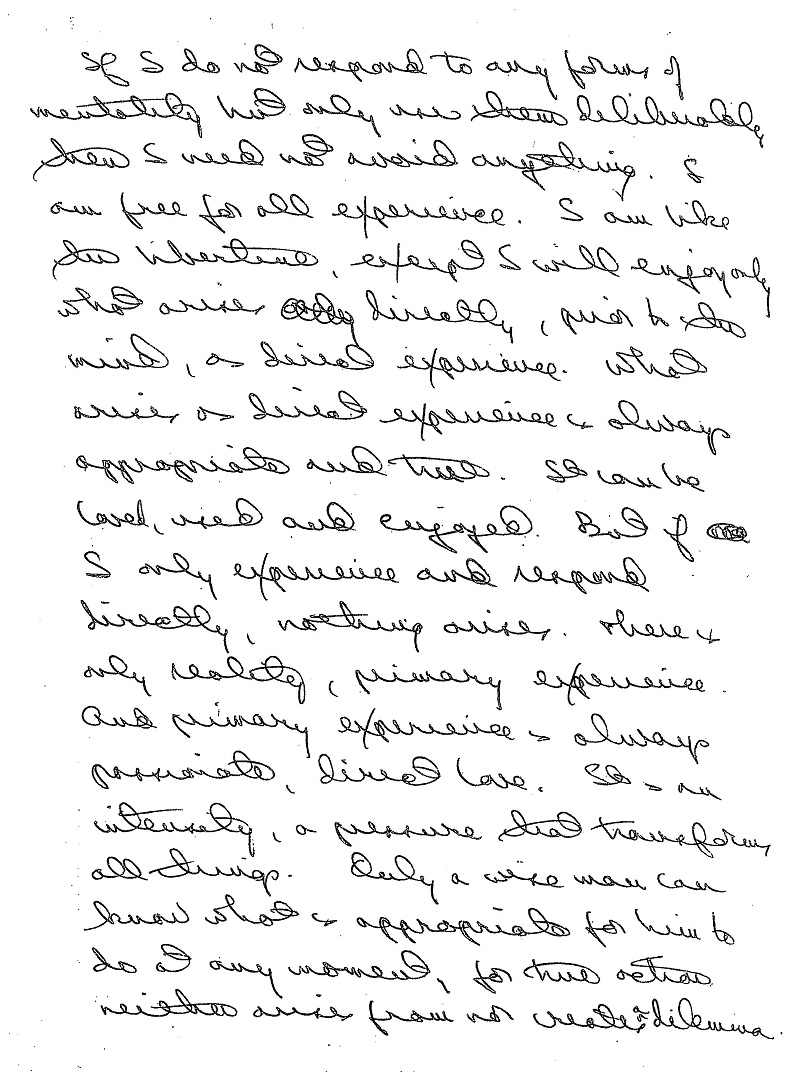

If I do not respond to any forms of mentality but only use them deliberately then I need not avoid anything. I am free for all experience. I am like the libertine, except I will enjoy only what arises directly, prior to the mind, as direct experience. What arises direct experience is always appropriate and true. It can be loved, used, and enjoyed. But if I only experience and respond directly, nothing arises. There is only reality, primary experience, and primary experience is always passionate direct love. it is an intensity, a pressure that transforms all things. Only a wise man can know what is appropriate for him to do at any moment, for true action neither arises from nor creates a dilemma.

“The motive force of real morality is the refusal to take on anything other than the form of love or to allow anything to rest in other than the form of love. Its foundation is radical understanding, but its force is love, the demand for love, the discipline of love, the radical action of love. Where there is no radical understanding there is also no morality, no love. And this absence is the condition the man of understanding finds in the world. Therefore, his moral life is difficult, requiring profound intelligence and action that is a paradox to the world. His attention is not driven to his own sacrifice or the manipulation of the world. He moves with subtle and dramatic intelligence, but the effects of his action are not the moralization of the world. He creates a moral world, an actual world of love, only where understanding also arises in the world.

There is a radical distinction to be made between the action of the man of understanding and the more or less ethical motivations of society. His action depends on understanding, whereas the social management’s of mankind now depend on external matters more or less independent of true consciousness. Therefore, his action is not a pattern for an external morality. He is not a model for the world. But he is the only moral hope of the world.

My approach to the lives of those I serve has duplicated the approach I made to my own life. I have approached them on the level of their ordinary dilemmas. I have even exploited and magnified their particular patterns of experience in myself. Then I have made these exploits the ground for some insight, some understanding, and as this understanding arose I have moved into more fundamental representations of their experience. By this I have hoped to move them into a radical consideration of their primary experiences and patterns.

But this manner of teaching is very exhausting and difficult for me. And very often I have devoted myself to people who are incapable or unwilling to involve themselves in a radical exercise. Therefore, my way of working with others has begun to change. I want my writing to replace my former work. Those who are capable of understanding should discover their lessons in relationship to the literature of understanding. And I will work personally only with those who have begun to work in a fundamental way.”

This manner of working will enable me to create a circle of intelligent people who can manifest the light and force I have to give on the highest level. At the same time, the instrument of my writing will work on its own to serve those now and in the future who will begin the understanding of the ordinary.

Franklin Jones (Adi Da Samraj), unpublished writing, 1971.

A Divine Fire

Unless we die, Father will not come in us. Kabir said: “either you have God or the `I.’ There cannot be two swords in one sheath. If God must come, `I’ must die.” – Yogi Ramsuratkumar

“Short term visitors … did not know that Yogi Ramsuratkumar was a ruthless taskmaster who wielded a flaming sword. To be near him with sincerity was to experience a literal internal fire that spared nothing in its path,” wrote Mariana Caplan, an American woman who was drawn into close circle of disciples during a period at six months in 1993.31

From her perspective, for the serious practitioner – one who was approaching Yogi Ramsuratkumar for something beyond relief of physical or emotional suffering, but rather for the purpose of dying into him, in the sense that Kabir described above – the work was often excruciating. “The egoic self that I mistakenly know myself to be suffered more intensely and more consistently in his company than in any other circumstance prior to, or since, that time. Yet so skillful was his capacity for egoic undoing that my ego would be made to flail about as if being scorched alive, while at the same time I would not know that he had anything to do with the suffering I was enduring. The light of His Self exposed my self – unadorned and unbuffered. To receive the privilege of his Fire of Love was to agree to have everything in its way burned to ash. These are not metaphors – exaggerated words to describe an intense emotional experience. It is my repeated experience of living in His proximity.”32

In detailing some of her experiences, Mariana explained that she was so attuned to him, by his grace, that his smallest movement would create a profound energetic shift in herself and others who were similarly resonant. “If he would move his elbow, the whole process would change. That movement became the world! We were in his work chamber. It was a slow motion play in darshan, and we would go on this energetic ride with him.”

Yogi Ramsuratkumar was literally a Divine furnace, burning away the impurities of those who approached him. “Every foot closer to his body, and the heat would rise intensely – an inner heat that was physical and not physical at the same time. When he called you up to give you prasad, just stepping two feet closer meant more burning. You knew you were fortunate, and you paid attention and you were grateful, but it was so hot. As you were burning like that, all the obstacles in between you and That would come up. So the mind would throw the garbage and the thoughts really fast. Meanwhile, he was giving you all this love. For me, encountering my self-hatred, I was upset about what I was doing in the face of all that blessing. There was such frustration that I didn’t know how to receive that blessing rightly. 33

Like many classic mystical accounts, Mariana described feeling, “Lost … no mind … definitely not cognitive … just in a `being’ space.”‘ The strongest overall impression for her was that she was completely at the effect of his love, his energy.

To this day Yogi Ramsuratkumar continues to be a dynamic force in her life and in her sadhana.

The purifying fire of Yogi Ramsuratkumar was sometimes a smoldering pile of embers, and on other days, a huge conflagration. “I loved to see him embody opposites of moods – move from sternness to kindness to peace to wittiness, within seconds,” explained Kirsti, a female sadhaka who lived most of her life in Tiruvannamalai. “He truly was alive on a very personal level in all his interactions. Even when he was `mean’ there was so much love and raw power behind it that I could just wonder what was taking place. His sternness or `meanness’ did not cling to mind or create guilt or resentment. His joyous straightforwardness prevented the mind from holding impressions of guilt or resentment.”34

When an individual could profit from some direct intervention, however, Yogi Ramsuratkumar did not hesitate to intervene. One of his attendants for many years, Selveraj, tells of a specific teaching communication that included an angry and even sarcastic response from Yogi Ramsuratkumar.

Typically, when Bhagwan’s car would arrive at the ashram, Selveraj was there to meet it. He would hold out his hand and the beggar would take it, saying “Thank you” with gracious regard.

One day, however, when Bhagwan said “Thank you,” Selveraj responded automatically, saying “Thank you” in return. The unconscious nature of this response ignited the Godman’s energy. “Thank you, thank you, thank you,” he repeated, with a tone of anger.

Selveraj pondered this interchange for a long time, wondering if he had done something wrong in the past few days that had warranted such a communication. On the contrary, he finally understood that the mistake was not in the past, but in the present. Yogi Ramsuratkumar expected him to be alert in every moment. In saying “thank you”. in a distracted manner, Selveraj had revealed his lack of attention to his work.

“So, Bhagwan was slowly working my heart. This is the main point. The guru will give the shock in a different way. We should remember all the time, God, and we should not be thinking about the things that have gone wrong.”35

A visitor from Canada was surprised one day when, in the midst of his conversation with the beggar, Swamiji fell asleep. As he received no response from the master, the visitor soon left.

When Yogi Ramsuratkumar woke up, another man asked him, “Swami, why did you fall asleep when that man was here?”

“Oh,” he said, “that man couldn’t hear what this beggar had to say.”36

On January 25, 1979, two Indian gentlemen visited the Yogi Ramsuratkumar late in the evening. They requested his blessings for a fund that had recently been established, named after a disciple of Ramalinga Swami. The master lay back listening and observing with intensity. Suddenly, as if moved by a strong wind, Yogi Ramsuratkumar sat up and demanded with great urgency that they go back to Madras. The two men were alarmed and confused, while Yogi Ramsuratkumar assured them that he would pray for their cause. “Make preparations to go to Madras. Go to Madras. I will pray.” He handed the two men a packet of biscuits.

“Swami? Swami?” asked one man, as he reached around in the darkness to find his shoes. He could not believe that they were being ushered out for abruptly. Clearly, there was no arguing with the beggar’s intention. He had his reasons.37

Jai Ram, another close attendant, felt the heat of Yogi Ramsuratkumar’s training in surrender. “It is very difficult to work for him, because he used to call himself `mad.’ His madness you could not predict. One day, He will suddenly send you out [out of his presence, away from him]. The next day, when you see him he will ask, `What do you feel?’ How he behaves in various situations, we cannot describe. Every action of his will hammer our ego; in some corner it will hit. We should not get into that [meaning, not support the ego]. Then only we can do his work. We have to learn this. You have to do exactly what he wants, and that you have to grasp. It took a lot of attention.”

One way in which the master “hammered egos” was in giving orders that had seemingly no logic or precedent. Sometimes these orders were repeated two, three, four or more times until the devotee received the message at the level it needed to penetrate.

Finally, Yogi Ramsuratkumar called Selveraj back for a fourth time, and this time he called Mani as well. “Mani, you tell Selveraj not to go there,” the beggar said, and Mani did as directed.

“Bhagwan, I will not go without your permission. Not only here, but wherever I go I will get permission from you,” Selveraj said, his words invoking a solemn promise with the

Godman.

Paradoxically, this strange interaction marked the beginning of his relationship of devotion and surrender to Yogi Ramsuratkumar.

It didn’t take large gestures for Yogi Ramsuratkumar to fry the ego of a visitor or devotee. It happened on several occasions that a person who assumed that he or she knew Bhagwan very well would tell Yogiji’s attendant, Selveraj, to inform the Godman of their arrival. This Selveraj would do. Nonetheless, when that person was presented to Bhagwan, he might ask them, “What is your name?” – thereby totally wounding the ego. Yogi Ramsuratkumar killed the ego many times with that one simple question.

Along similar lines, one time a swami came from Kerala, did a very fancy puja, and received lots and lots of attention from Yogi Ramsuratkumar. The next year, assuming that he would receive the same fanfare, the man had someone go to Bhagwan and say that he was there, announcing self-assuredly, “He will see me right away.”

When Bhagwan got this news, he looked up and saw the man standing by the back door. Yogiji sent word, “Let him sit at the corner,” and arranged that a chair be brought to the man, who sat in the corner for the rest of the program. The beggar never called this man up to the dais.

In 1995, Selveraj was working for salary at the ashram, but had not yet established a relationship of devotee-to-guru with Yogi Ramsuratkumar. He had received Mani’s permission to go to his mother-in-law’s home for a holiday, but had failed to inform Bhagwan.

“When I went to my house to get ready for the time to leave, something was grabbing me to come back to the ashram. I got the idea that I should drop that program [abandon the idea of a holiday as previously determined],” Selveraj explained.

But, before Selveraj could get there, Yogi Ramsuratkumar arrived at the ashram. It was 10 A.M., just prior to the morning darshan, and the Godchild was acutely aware that Selveraj was missing.

“He was shouting at the top of his voice, `Where is Selveraj? Where is Selveraj?’ and everybody got shocked. Mani told that he had given permission.”

“If he goes there it is very dangerous. He should not go there,” Yogiji said. Upon learning this information, the Godman sent someone to Selveraj’s home, carrying the message, “Bhagwan wants to see you.” The young man immediately set out.

When Yogi Ramsuratkumar laid eyes on his attendant a few minutes later, he studied him seriously and instructed: “Selveraj, you don’t go. If you go, you will meet [something] very dangerous.”

Instantly, the younger man replied, “Okay, Bhagwan,” and then moved to take up his usual post at the temple door.

“Three times he called me back to him, and each time he said the same thing; and each time I said, “Okay Bhagwan, I won’t go there.”

pp. 422 – 425 Yogi Ramsuratkumar – Under the Punnai Tree. M. Young. Holm Press, 2003.

“Right in the beginning he told me in so many words that spiritual life requires the shedding of the ego. Lesson one, lesson two, lesson three, lesson hundred, lesson infinity!

In 1994 and 1995 Devaki and the Sudama sisters were finding out what it means to live in close physical proximity to the pervasive transformational power of Yogi Ramsuratkumar. The spiritual master is like the sun in the solar system: the closer you are to the sun’s rays, the hotter it gets until you are incinerated – burned to a crisp.

However, using the ideas as a metaphor for spiritual life, annihilation of the separate self.

As Yogi Ramsuratkumar said, “The best sadhana is to be nears one’s guru, to obey and serve him. All other sadhanas are only after that. This is the best sadhana.”1

1. Ma Devaki, “The Divine Beggar on Himself,” Saranagatham, January 2003, p.33.

Devaki and the Sudama sisters were learning to live in close proximity to a spiritual sun, and in order to serve Yogi Ramsuratkumar in the way that they were call to do, they had to be instructed, prepared and purified – they were in a kind of spiritual boot camp, in training for being able to “Father’s work.” They had renounced the world and worldly desires, and their lives were not about sacrifice and service, and Yogi Ramsuratkumar used the mundane circumstances of daily life as the vessel in which the dross was purified from the bodies and minds in order to reveal the gold.

Much of their process of purification took place in the ordinary circumstances of everyday activities. For example, Yogi Ramsuratkumar had an extremely meticulous sensibility; he wanted everything done in a certain way. From his point of view, when something was placed on the table one fraction of an inch off the mark as he saw it, it affected everything – even the entire cosmos. Another form of purification was the rigorous schedule the Sudama sisters kept, following Bhagawan’s rhythms and commands regarding food, sleep and activity.

It was already very clear that Devaki had to play a very specific role; Bhagawan told them that she was the divine mother, and that all the Sudama sisters should be considered as “Ma’s.” They had absolutely no personal life. Everyone was expected to obey Bhagawan implicitly, and to have no voice in matters. For Vijayalakshmi, who had joined the group also used to giving orders and being highly respected in her job, this was not an easy task – nor was it easy for any of the women. Yogi Ramsuratkumar expected a great and arduous sadhana from all four of them.

If Devaki was reading to him and she fell asleep or even closed her eyes for a few seconds, he would immediately wake her up, saying, “Read!” If she had a bad headache, he expected her to go on with her work. He would not allow her to rest, and every day was filled with the rigorous schedule of public darshans and all the needs of the burgeoning new ashram. Bhagawan expected Devaki and Sudama sisters to be at his side every moment of the day – whether they were sick, healthy, happy, sad, tired or full of energy really didn’t matter. The normal concerns of the human personality, psychology or the needs of the physical body were not longer relevant.

“No, no,” he would say if Devaki wanted to rest, “there is no need for it! You just stay with this beggar, that will do.” Sleep was not necessary. When Devaki became bitter about her failings, saying, “Bhagawan, I fail so miserably! What is the use of my living wit you, I’m not able to serve you nicely?”

“Stop crying! You have a very bright future,” the beggar admonished. “Father will shape you for this work!” At other times, when the work was overwhelming and things seem bleak with the criticisms and distrust that came from other devotees, Devaki would get furious with herself and feel powerless in the fact of her own shortcomings:

I would be miserable at my own failings and then if I complained to him, he would say, “No, no, Devaki, you are doing wonderful work for my Father. See…it is very difficult to live with this beggar, even for half an hour, Devaki. Even for half an hour. People cannot live with this beggar for half an hour! Only Father wants to be with this beggar. But Devaki has lived with this beggar so long. Devaki is managing so well.” And then he would encourage me with such nice words and love. He would be so nice to me at that time, and then, he often said, “It is very difficult to live with this beggar, for anybody. That itself is tapas.” Just living with him adjusting to him. No matter how many mistakes we make. It was a big challenge being with him because, for one thing, I was a totally different kind of personality. The first year was terrible to adjust, and he made it very plain in the beginning that I would have to surrender my ego!

The intensity that was felt in the presence of the beggar saint was an experience shared by those who were close to him. Ravi, the driver of his car, who held his hand several times every day as he helped the beggar in and out of the car and into Sudama House, the temple, dining hall or wherever he was going, described this feeling as “heat and pressure.” This was a subtle energetic phenomenon, and yet it was a bodily experience as palpable and tangible as the heart one experiences when standing in the hot noonday Indian sun. Beyond this crucible of heat and pressure, at every turn, at the slightest manifestation of ego on the part of those who were close to him and served him daily, the master pointed it out and corrected it, in one way or another. Vijayalakshmi went through this process of purification and more – the basic context with which she approached life had to shift:

I used to feel really a match for him! I had very nice quarrels with him! Looking back, I

wish I hadn’t, but then I was totally unexposed to spiritual life. It was not a question of my not wanting to let go of my ego, but, one never know about it, what exactly it is. That is the real problem. I mean, how to become something like zero, in no time at all? Right in the beginning he told me in so many words that spiritual life requires the shedding of the ego. Lesson one, lesson two, lesson three, lesson hundred, lesson infinity!

When Yogi Ramsuratkumar gave a task to be done, he wanted it done immediately. If he gave Devaki some small task and she was gone from the room for five minutes he would be calling, “Devaki! Devaki!” He was a relentless taskmaster in one moment and in the next moment he was the divine child, calling out for mother – “Devaki!” Then she would come and show him how to do some very simple thing, “Like this, Bhagawan,” she would say. All together, Yogi Ramsuratkumar and the four women were a spiritual family, and often they were like children together, with many playful interchanges, laughter and the pure enjoyment of good company. Yogi Ramsuratkumar’s marvelous spontaneity and sense of humor came through at the most difficult times.

At other times, it was just tapas. When Devaki wasn’t reading to Bhagawan for days on end, she was doing japa and nama with the Sudama sisters, especially Vijayalakshmi, until they were all exhausted. During one of these times when she was sleeping only two or three hours at night; not only was she exhausted, but her nerves were worn thin. When Devaki finally protested to Yogi Ramsuratkumar in a flair of anger, he started dancing. Devaki recalled:

One time when I had been up for days with no sleep, and it was just going on and on, I got angry with him and protested. He started dancing! This made me even angrier and I imitated him – I started dancing too! And then he started laughing, laughing, laughing, until I started laughing too. This is how is was….we were a family together. It is amazing how he avoided controversy and bad stories – a saint living with four women! But he was so pure, so stainless…

A primary focus of sadhana for Vijayalakshmi was to do nama japa all day long. At time this became so all-consuming that her head would spin in the morning and cause all kinds of sensations to arise because of the power of the nama japa and the spiritual forces it unleashed in her. Sometime she cried from the sheer gratitude and love that she felt for Bhagawan.