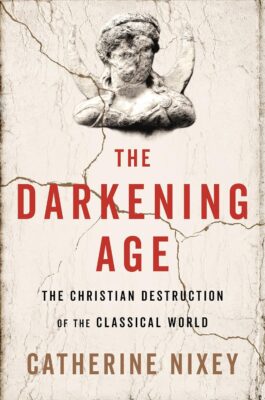

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

“A Time of Tyranny and Crisis”

Moreover, we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism.

Justinian Code, I.II.10.2

The philosopher Damascius was a brave man: you had to be to see what he had seen and still be a philosopher. But as he walked through the streets of Athens in ad 529 and heard the new laws bellowed out in the town’s crowded squares, even he must have felt the stirrings of unease.1 He was a man who had known persecution at the hands of the Christians before. He would have been a fool not to recognize the signs that it was beginning again.

As a young man, Damascius had studied philosophy in Alexandria, the city of the murdered Hypatia.2 He had not been there for long when the city had turned, once again, on its philosophers. The persecution had begun dramatically. A violent attack on a Christian by some non-Christian students had started a chain of reprisals in which philosophers and pagans were targeted. Christian monks, armed with an axe, had raided, searched, then demolished a house accused of being a shrine to “demonic” idols.3 The violence had spread and Christians had found and collected all images of the old gods from across Alexandria, from the bathhouses and from people’s homes. They had placed them on a pyre in the center of the city and burned them. As the Christian chronicler Zachariah of Mytilene comfortably observed, Christ had declared that he had “given you the authority to tread on snakes and scorpions, and over all enemy power.”4

For Damascius and his fellow philosophers, however, all that had been a mere prelude to what came next. Soon afterwards, an imperial officer had been sent to Alexandria to investigate paganism. The investigation had rapidly turned to persecution. This was when philosophers had been tortured by being hung up by cords and when Damascius’s own brother had been beaten with cudgels—and, to Damascius’s great pride, had remained silent.5

Philosophers weren’t only attacked in Alexandria—and they didn’t always bear the attacks with such mute suffering. When one philosopher was being beaten in a courtroom in Constantinople, the blood started flowing down his back. The man allowed some of it to pool in his hand. You savage, he said to the judge. “You want to devour the flesh of men? Then have something to wash it down with.” He threw a palmful of blood over the official: “Drink this wine!”6

Damascius would come out of the Alexandrian persecutions a changed man. He had never originally intended to study philosophy at all; the privileged son of wealthy parents from Damascus, he had hoped to pursue the more glamorous life of a public orator. Mere chance had brought him into the philosophical fold, but once he had converted to the cause he not only devoted his life to philosophy, he also risked his life for it, repeatedly. He would develop a deep contempt for anyone who did anything less, and in his writings poured scorn on those who were adept at talking about what should be done but inept at actually doing anything.7 Words without deeds were useless. Action, then. When the persecutions in Alexandria became intolerable, Damascius decided to flee. In secret, he hurried with his teacher, Isidore, to the harbor and boarded a boat. Their final destination was Greece, and Athens, the most famous city in the history of Western philosophy.

It was now almost four decades since Damascius had escaped to Athens as an intellectual exile. In that time, a lot had changed. When he had arrived in the city he had been a young man; now he was almost seventy. But he was still as energetic as ever, and as he walked about Athens in his distinctive philosopher’s cloak—the same austere cloak that Hypatia had worn—many of the citizens would have recognized him. For this emigre was now not only an established fixture of Athenian philosophy and a prolific author, but also the successful head of one of the city’s philosophical schools: the Academy. To say “one of” is to diminish this institution s importance: it was perhaps the most famous school in Athens, indeed in the entire Roman Empire. It traced its history back almost a thousand years and it would leave its linguistic traces on Europe and America for two thousand years to come. Every modern academy, academic and akademie owes its name to it.8

Since he had crossed the wine-dark sea, fife had gone well for Damascius—astonishingly well, given the turbulence he had left behind. In Alexandria, Christian torture, murder and destruction had had its effect on the intellectual life of the city. After Hypatia’s murder the numbers of philosophers in Alexandria and the quality of what was being taught there had, unsurprisingly, declined rapidly. In the writings of Alexandrian authors there is a clear mood of depression, verging on despair. Many, like Damascius, had left.

In fifth-century Athens, the Church was far less powerful and considerably less aggressive. Its intellectuals had felt pressure nonetheless. Pagan philosophers who flagrantly opposed Christianity paid for their dissent. The city was rife with informers and city officials listened to them. One of Damascius’s predecessors had exasperated the authorities so much that he had fled, escaping—narrowly—with his fife and his property. Another philosopher so vexed the city’s Christians by his unrepentant “pagan” ways that he had had to go into exile for a year to get away from the “vulture-like men” who now watched over Athens. In an act that could hardly have been more symbolic of their intellectual intentions, the Christians had built a basilica in the middle of what had once been a library. The Athens that had been so quarrelsome, so gloriously and unrepentantly argumentative, was being silenced. This was an increasingly tense, strained world. It was, as another author and friend of Damascius put it, “a time of tyranny and crisis.”9

The very fabric of the city had changed. Its pagan festivals had been stopped, its temples closed and, as in Alexandria, the skyline of the city had been desecrated—here, by the removal of Phidias’s great figure of Athena. Even Athens’s fine philosophical traditions had been debased—though as much by incompetent philosophers as by anything the Christians did. When Damascius and his teacher arrived in the city at the end of the fifth century, they had been utterly underwhelmed by it. “Nowadays,” Isidore observed, “philosophy stands not on a razor’s edge but truly on the brink of extreme old age.”10 Damascius had “never heard of philosophy being so despised in Athens” as it was then.11 It is a mark of quite how uncongenial the empire had become to non-Christians that despite this, Athens had seemed the most congenial place for them to flee to.

Yet Damascius had turned Athenian philosophy around. In the decades since his arrival in the city, he had taken its philosophical schools from decrepitude to international success. Once again, the Academy was attracting what one ancient writer called the “quintessential flower of the philosophers of our age” to come there to study.12 Its philosophers were hugely prolific—and knowledgeable: Damascius and his fellow scholars were producing works that have been called the most learned documents ever to have been produced by the ancient world.13 As well as all of this, the inexhaustible Damascius would also find time to deliver densely academic lectures on Aristotle and Plato and produce a series of subtle works on metaphysical philosophy, Plato and mathematics.14

Despite his success, Damascius had not forgotten what he had seen in Alexandria—and had not forgiven it, either. His writings show a never-failing contempt for the Christians. He had seen the power of Christian zeal in action. His brother had

been tortured by it. His teacher had been exiled by it. And, in the year 529, zealotry was once again in evidence. Christianity had long ago announced that all pagans had been wiped out.15 Now, finally, reality was to be forced to fall in with the triumphant rhetoric.

The determination that lay behind this threat was not only felt in Athens in this period. It was in ad 529, the very same year in which the atmosphere in Athens began to worsen, that St. Benedict destroyed that shrine to Apollo in Monte Cassino.16 A few years later, the emperor Justinian decided to destroy the frieze in the beautiful temple of Isis at Philae in Egypt: a Christian general and his troops duly methodically smashed the faces and hands off the demonic images. Go to Philae today, and you can see the frieze—much of it still intact, except that many of the carved figures are missing faces and hands.

In Athens, it wouldn’t be temples but something far more intangible—and potentially far more dangerous—that was targeted: philosophy. Previous attacks on Damascius and his scholars had largely been driven by local enthusiasms: a violently aggressive band of Alexandrian monks here, an officious local official there. But this attack was something new. It came not from the enthusiasm of a hostile local power; it came in the form of a law—from the emperor himself. Actually, what befell the philosophers in ad 529 was not just one single law but a staccato burst of legal aggression issued by Justinian. “Your Clemency . . . the Glorious and Indulgent” Justinian is how laws of this period referred to him. Justinian’s reverence, the legal code of the time announced, shone out “as a specially pure light, like that of a star,” while Justinian himself was referred to as “Your Holiness,” the “glorious emperor.”17

There was little glorious or indulgent about what was coming. And there was certainly nothing that was clement. This was the end. The “impious and wicked pagans” were to be allowed to continue in their “insane error” no longer.18 Anyone who refused salvation in the next life would, from now on, be all but damned in this one. A series of legal hammer blows fell: Anyone who offered sacrifice would be executed. Anyone who worshipped statues would be executed. Anyone who was baptized—but who then continued to sacrifice—they, too, would be executed.19

The laws went further. This was no longer mere prohibition of other religious practices. It was the active enforcement of Christianity on every single, sinful pagan in the empire. The roads to error were being closed, forcefully. Everyone now had to become Christian. Every single person in the empire who had not yet been baptized now had to come forward immediately, go to the holy churches and “entirely abandon the former error [and] receive saving baptism.” Those who refused would be stripped of all their property, movable and immovable, lose their civil rights, be left in penury and, “in addition”—as if what had gone before was not punishment but mere preamble —they would be “subject to the proper punishment.” If any man did not immediately hurry to the “holy churches” with his family and force them also to be baptized, then he would suffer all of the above—and then he would be exiled. The “insane error” of paganism was to be wiped from the face of the earth.20

In such an atmosphere, it took something for a law to stand out as particularly repressive. Yet one law did. Out of all the froth and fury that was being issued from the government at the time, one law would become infamous for the next 1,500 years. Read this law and, in comparison to some of Justinian s other edicts, it sounds almost underwhelming. Filed under the usual dull bureaucratic subheading, it is now known as “Law 1.11.10.2.” “Moreover,” it reads, “we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism” so that they might not “corrupt the souls of their disciples.”21 The law goes on, adding a finicky detail or two about pay, but largely that is it.

Its consequences were formidable. This was the law that forced Damascius and his followers to leave Athens. It was this law that caused the Academy to close. It was this law that led the English scholar Edward Gibbon to declare that the entirety of the barbarian invasions had been less damaging to Athenian philosophy than Christianity was.22 This law’s consequences were described more simply by later historians. It was from this moment, they said, that a Dark Age began to descend upon Europe.

It didn’t descend immediately. Like most “turning points” in history this one was in reality more of a tilting. Night didn’t suddenly fall; the world did not suddenly go black. At the very most it merely dimmed, in one place, a little. The immediate consequences of the law were less dramatic than the language in which it was written. For a while, Damascius and his fellow philosophers continued to teach and their school continued to function. They almost certainly kept giving lectures; they definitely continued writing books. And it is impossible to imagine that the philosophers would have stopped bickering among themselves about the minutiae of Neoplatonic interpretation.

Little else is known from this period apart from one tantalizing possibility. It seems that we might know precisely which building these men, the last philosophers of the Academy, the last true philosophers of Athens, occupied during their final months and days in the city.23 In the 1970s, excavations on the Athenian Agora uncovered an enviably elegant house. Today, this Roman-style villa is known by the unprepossessing name of “House C.” This does little justice to its beauty. From the outside, admittedly, the house was unassuming enough. Set in a narrow street, just off the main square of the Agora, it presented no more than a featureless and rather dull wall to the outside world. Only this wall’s length, an impressive 40-odd meters, and its location, in the shadow of the Acropolis, might have hinted discreetly at something more.

Step through the door in that wall, out of the sunshine of an Athenian afternoon, into a dim entrance hall, and you would have entered another world. After the noise and the filth of an Athenian street, you would have found yourself in a cool, shaded courtyard with a colonnade running round all sides. The walls and floor were stone, cool to the touch even on the hottest day, and from somewhere just beyond the courtyard came the sound, tantalizing in the heat, of water. More remarkable than all of this, however, was the art.

You can tell a lot from the art that people choose for their house. The twelve statues that have been recovered from House C were not the collection of an ignorant nouveau. It isn’t just the quality of their craftsmanship that impresses— though that is extraordinary: the delicate lines on this woman’s mouth, the plump pout on that statue of the goddess Nemesis, the realism that was able to show individual hairs on the eyebrows of that emperor . . . What also impresses about these statues is their age. These pieces were antique—ancient —even when the philosophers lived here: in Damascius’s day one of them was already over eight hundred years old.24 One of the most interesting works was a large but delicately carved relief that depicted the gods Hermes, Apollo and Pan, and a cluster of nymphs, all overlooked by a bearded Zeus. This art collection was an eclectic, antiquarian delight that would have impressed visitors in any century. In the early sixth century, when religious artworks in the city outside the walls of House C had been relentlessly smashed, attacked and defaced, it must have been astonishing.

Walk on, past the statues, over the light-dark stripes of the shadows cast by the stone columns, and the sound of water would have grown louder still. In a world in which piped water was an expensive rarity, this was a house that dripped, quite literally, with wealth. Go down some steps and here, beneath generous arches, bright in the Athenian sun, was a large semicircular pool and shrine. It must have been a delightful place to stop on a punishingly hot Athenian afternoon. Like Pliny the Younger, reveling at the sight of the glass-clear waters at a shrine to the river god, one could have worshipped not only divinity but beauty here.

It is entirely plausible that House C was the place where Damascius and his fellow scholars spent their last years in Athens. It would have been perfect for them. Everything they might have needed was here, from lecture rooms to teach in, to shrines to the old gods to worship at, and a large dining room—decorated with scenes featuring those gods—at which Damascius could have given the dinners that tradition required him to hold.

At such meals Damascius must have made for an entertaining, albeit sharp-tongued, companion. It’s quite clear from his writings that he had an excellent eye for anecdote: it is to his pen that history owes the story of Hypatia and her sanitary- towel.25 It is also clear that he would not have been willing to sugar his speech to suit his listener. His accounts of his fellow philosophers have a warts-and-all feel to them. One scholar, whose mind most think is perfect, is dismissed by him as being only of “uneven intelligence.”26 Others receive similar slights. Still, barbed or not, the company would have been fun and-, in its way, exhilarating. An illicit glamour must have clung to this cool, otherworldly courtyard and to its philosophers as they walked about in their defiant philosophers’ cloaks, criticizing each other’s theories and arguing about forbidden things.

Without a doubt they would have talked, too, about what was fast becoming the most important force in their lives: Christianity. As the modern scholar Alan Cameron has put it: “In 529 the philosophers of Athens were threatened with the destruction of their entire way of life.”27 The Christians were behind this—yet you will search almost in vain for the word “Christian” in most of the writings of the philosophers. That is not to say that evidence of them is not there. It is. The miasmatic presence of the religion is keenly felt on countless pages: it is Christians who are driving persecutions, torturing

their colleagues, pushing philosophers into exile. Damascius and his fellow scholars loathed the religion and its uncompromising leaders. Even Damascius’s famously mild and gentle teacher, Isidore, “found them absolutely repulsive”; he considered them “irreparably polluted, and nothing whatever could constrain him to accept their company.”28

But the actual word Christian is missing. As if the very syllables were too distasteful for them to pronounce, the philosophers resorted to elaborate circumlocutions. At times, the names they gave them were muted. With a masterful understatement, the present system of Christian rule, with its torture, murder and persecution, was referred to as “the present situation” or “the prevailing circumstances.”29 At another time the Christians became—perhaps a reference to those stolen and desecrated statues—“the people who move the immovable.”30 At other times the names were blunter: the Christians were “the vultures” or, more simply still, “the tyrant.”31

Other phrases carried a contemptuous intellectual sneer. Greek literature is awash with hideously rebarbative creatures, and the philosophers turned to these to convey the horror of their situation: the Christians started to be referred to as “the Giants” and the “Cyclops.” These particular names seem, at first sight, an odd choice. These are not the most repellent monsters in the Greek canon; Homer alone could have offered the maneating monster Scylla as a more obvious insult. That would have missed the point. The Giants and the Cyclops of Greek myth aren’t terrible because they are not like men— they are terrible because they are. They belong to the uncanny yalley of Greek monsters: they look, at first glance, like civilized humans yet they lack all the attributes of civilization. They are boorish, base, ill-educated, thuggish. They are almost men, but not quite—and all the more hideous for that. It was, for these philosophers, the perfect analogy. When that philosopher had been beaten till the blood ran down his back, the precise insult that he hurled at the judge had been: “There, Cyclops. Drink the wine, now that you have devoured the human flesh.”32

If the philosophers loathed the Christians then the Christian authorities, for their part, found themselves profoundly irritated by the philosophers. Some of what they taught expressly and intolerably contradicted Christian doctrine. Any suggestion from philosophers that the world was eternal, for example, could not be countenanced if the doctrine of the Creation was to be believed. Moreover, this was an age in which philosophy and theology frequently blended into one (to Christian eyes) ominous whole.33 Worse still, what was being studied in the Academy was not pure Plato but the dubious Neoplatonism—much to the horror of later scribes. A tenth-century text that preserves some of Damascius’s writings intersperses quotations from them with bursts of Christian revulsion towards this “impious” man,34 and the “impossible, unbelievable, ill-conceived marvels and folly” that he, in his “godlessness and impiety,” believed.35

The Christians would not need to put up with such irritations for much longer. In ad 529 the law forbade the philosophers—suffering, as they did, from the “insanity of paganism” —from teaching.36

What did the philosophers say to each other as they walked along the cool marble hallways of House C? What would have gone through their minds when they learned that, if they didn’t immediately present themselves for baptism then, according to the law, they would be stripped of all their rights and their possessions—including that wonderful villa? What would they have thought when they heard that, if they did accept baptism and later lapsed, and put an offering at the shrine next to their beautiful pool, then, according to the law, their fate should be execution?

What conversations must they have had in the months that followed as the new laws began to take effect and as that flow of brilliant pupils to those marble classrooms had slowly petered out; as the fees had stopped coming in and dented their wealth; and as the bequests they had once relied on had finally dried up?

Like so much else from this period, it is impossible to know. It is thought that one of the philosophers wrote an account of what happened next but if so it has been lost. Some facts, through the thin web of surviving texts, are clear.37 It is clear that the philosophers didn’t leave immediately after the infamous law was announced. They seem, instead, to have lain low—not a mark of the cowardly man, in their philosophy, but the sensible one. Almost two hundred years of aggressive Christianity had taught them the value of this. Philosophers, as one of their number put it, should let “sleeping beasts lie” and “at such times of crisis, be careful to avoid clashes with the authorities and untimely displays of outspokenness.”38

But the sleeping beasts didn’t lie. On the contrary, the Christian “beasts” started to roar with ever-increasing ferocity. Then the confiscations began. The philosophers couldn’t earn money; they couldn’t work; they couldn’t practice their religion, and now they couldn’t even hold on to what property they did have. By about 532, it seems that life had become intolerable for them. They decided to leave. Athens, the mother of Western philosophy, was no longer a place for philosophers —or at any rate for philosophers who refused to turn their philosophical tools to suit their Christian masters.

Damascius was now in his late sixties; yet he was not going to give up. He had traveled thousands of miles to get this far. He would now simply have to travel a few thousand more. His sense of duty demanded it. “A desire to do good is not enough,” he wrote. “One also needs strength of character and single-mindedness.”39 Still, even by Damascius’s standards the journey that he decided on was a bold one. The philosophers had heard that there was a new king in Persia, King Khosrow. He was renowned as a lover of literature and said to be a great student of philosophy. The rumors were beguiling: he had had whole works translated from Greek into Persian for him to read. His mind was filled with the doctrines of Plato—he even, it was whispered, understood the fiendishly difficult Timaeus. Persia itself received a similarly excitable billing. This was a land so justly ruled that it suffered from no theft, brigandage or crime. It was, in short, the land of Plato’s philosopher king.

The journey would not be easy. Its length alone was daunting. Damascius, however, was not a man to be put off by fear. “Nothing human is worth as much as a clear conscience,” he had once written. ‘A man should [never] give greater importance to anything other than truth—not the danger of an impending struggle, nor a difficult task from which one turns away in fear.”40

And so it was that one day, probably about three years after Law 1.11.10.2 was issued, these seven men, the last philosophers of the great Academy, set out from Athens. For the second time in his life, Damascius had been made an exile by the Christians. For the second time in his life, he would have had to pack his bags, bundling up his possessions and his books as he had done in Alexandria.41 He had arrived in Athens as a young man and an exile. Since then, he had achieved so much. He had saved Athenian philosophy and made the Academy the great-, est philosophical school in the empire. And he had done all this while tiptoeing round the “sleeping beasts” of the Christians.

It hadn’t been enough. Damascius was, once again, creeping out of a city like a criminal. More than that. Not like a criminal: as a criminal. And one who, as the hysterical language of the laws put it, was insane, wicked and iniquitous. Their beautiful house was prepared for desertion. In 532, the philosophers finally left Athens. The Academy closed. True—free—Athenian philosophy was over.

The trip was not a success. Far from being a society of such perfect justice that there was no crime, they discovered aland where the poor were treated with even more brutality and in-

humanity than at home. They were dismayed to discover that Persian men took multiple wives—and even more dismayed to learn that they still committed adultery, a state of affairs that seemed to bother them less for the infidelity than for the incompetence. Almost more upsetting than the treatment of the living was the Persians’ treatment of the dead: according to ancient Zoroastrian custom, corpses were not immediately buried but left above the ground to be eaten by dogs. In Greek culture this was profoundly shameful: The Hiad opens by describing how the war had “hurled down to Hades many mighty souls of heroes, making their bodies the prey to dogs and the birds’ feasting.”42 In Homer, it is the epitome of humiliation. In Persia, it was normal practice.

The philosophers were also disappointed in their host, King Khosrow. They had hoped for a philosopher king, but found instead “a fool.” Far from being well read, Khosrow’s famed “great learning” amounted to no more than an interest in “a smattering of literature.”43 Far from being an acute Platonic intellect this man, it was said, was the sort of intellectual lightweight who could be taken in by charlatans. A favorite at Khosrow’s court was a drunken Greek who mainly spent his days eating, drinking and then impressing people by saying the odd clever thing. An intelligence of sorts, but not the kind to impress the austere philosophers of Athens.

Damascius and his philosophers were bitterly downcast. Khosrow, who along with his lack of perspicacity in philosophical matters seems to have had a certain blithe unawareness in social ones, doesn’t seem to have noticed their disgust and, regarding them with affection, even invited them to stay on longer. They declined. Reproaching themselves for ever having come, they decided to return home as soon as they possibly could. According to one historian, their somewhat melodramatic feeling was that “merely to set foot on Roman territory, even if it meant instant death, was preferable to a life of distinction in Persia.”44

It seems that the philosophers underestimated their host, however. For while they might prefer instant death to remaining in Persia, Khosrow had gone out of his way to protect them. At the time when they were leaving court, the king had fortuitously been concluding a peace treaty with Emperor Justinian. Khosrow now used his military sway with Justinian to extort safe passage home for the philosophers. The precise wording of this clause has been lost but its essence has been preserved: the treaty demanded that “the philosophers should be allowed to return to their homes and to live out their lives in peace without being compelled to alter their traditional religious beliefs or to accept any view which did not coincide with them.”45 This clause was the only declaration of ideological toleration that Justinian would ever sign. It was, in some ways, a liberal landmark—and a sign of how illiberal the empire had become that it was needed at all.

The philosophers, homeless yet again, set out for a final time together. Their journey must have been a miserable one. What happened to them next is not certain. Some scattered facts remain. The philosophers do indeed seem to have returned to the Roman Empire, but not to Athens. It is certain that they didn’t give up philosophy. Scraps of their writings drift back to us: an epigram that is almost certainly by Damascius; a treatise from another philosopher, entitled “Solutions to those points that Khosrow, King of the Persians, was considering.”46 They had been exiled, outlawed and impoverished but they had still not relinquished philosophy.

And then, slowly, with a whisper rather than a shout, the philosophers are gone. Their writings peter out. The men, scattered across the empire, die.

The philosophy they had lived for starts to die itself. Some strands of ancient philosophy live on, preserved by the hands of some Christian philosophers—but it is not the same. Works that have to agree with the pre-ordained doctrines of a church are theology, not philosophy. Free philosophy has gone. The great destruction of classical texts gathers pace. The writings of the Greeks “have all perished and are obliterated”: that was what John Chrysostom had said. He hadn’t been quite right, then; but time would bring greater truth to his boast. Undefended by pagan philosophers or institutions, and disliked by many of the monks who were copying them out, these texts start to disappear. Monasteries start to erase the works of Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca and Archimedes. “Heretical”—and brilliant—ideas crumble into dust. Pliny is scraped from the page. Cicero and Seneca are overwritten. Archimedes is covered over. Every single work of Democritus and his heretical “atomism” vanishes. Ninety percent of all classical literature fades away.

Centuries later, an Arab traveler would visit a town on the edge of Europe and reflect on what had happened in the Roman Empire. “During the early days of the empire of the Rum,” he wrote—meaning the Roman and Byzantine Empire — “the sciences were honoured and enjoyed universal respect. From an already solid and grandiose foundation, they were raised to greater heights every day, until the Christian religion made its appearance among the Rum; this was a fatal blow to the edifice of learning; its traces disappeared and its pathways were effaced.”47

There was one final loss, too. This loss is even more rarely remembered than all the others, but in its way it is almost as important. The very memory that there was any opposition at all to Christianity faded. The idea that philosophers might have fought fiercely, with all they had, against Christianity was —is—passed over. The memory that many were alarmed at the spread of this violently intolerant religion fades from view. The idea that many were not delighted but instead disgusted by the sight of burning and demolished temples was—is— brushed aside. The idea that intellectuals were appalled—and scared—by the sight of books burning on pyres is forgotten.

Christianity told the generations that followed that their victory over the old world was celebrated by all, and the generations that followed believed it.

The pages of history go silent. But the stones of Athens provide a small coda to the story of the seven philosophers. It is clear, from the archaeological evidence, that the grand villa on the slopes of the Acropolis was confiscated not long after the philosophers left. It is also clear that it was given to a new Christian owner.

Whoever this Christian was, they had little time for the ancient art that filled the house. The beautiful pool was turned into a baptistery. The statues above it were evidently considered intolerable: the finely wrought images of Zeus, Apollo and Pan were hacked away. Mutilated stumps are now all that remain of the faces of the gods, ugly and incongruous above the still-delicate bodies. The statues were tossed into the well. The mosaic on the floor of the dining room fared little better. Its great central panel, which had contained another pagan scene, was roughly removed. A crude cross pattern, of vastly inferior workmanship, was laid in its place.

The lovely statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, suffered as badly as the statue of Athena in Palmyra had. Not only was she beheaded, she was then, a final humiliation, placed face-down in the corner of a courtyard to be used as a step. Over the coming years, her back would be worn away as the goddess of wisdom was ground down by generations of Christian feet.48

The “triumph” of Christianity was complete.

1. The manuscript of the Justinian Code is corrupted at this point, making precise dating difficult: AD 529 is the generally accepted date of this. There are two laws that are relevant here; I focus on the second.

2. For Damascius’s enthusiasm for her, see PH, 106A.

3. Zachariah of Mytilene, The Life of Severus, 26-33; PH, 53.

4. Zachariah of Mytilene, The Life of Severus, 30.

5. PH, 119.

6. PH, 106.

7. PH, 124.

8. Athanassiadi (1993), 4; Marinus, Life of Proclus, 10; 26.

9. Simplicius, epilogue on commentary on Enchiridion, quoted in Cameron (1969), 14-

10. Isidore, quoted in PH, 150.

11. PH, 145.

12. Agathias, Histories, 2.30.2.

13. According to Cameron (1969), 22.

14. Stromberg (1946), 176-77.

15. C. Th., 16.10.22 of April 423.

- The manuscript of the Justinian Code is corrupted at this point, making precise dating difficult: ad 529 is the generally accepted date of this. There are two laws that are relevant here; I focus on the second.

- For Damascius’s enthusiasm for her, see PH,

- Zachariah of Mytilene, The Life of Severus, 26-33; PH,

- Zachariah of Mytilene, The Life of Severus,

- PH,

- PH,

- PH,

- Athanassiadi (1993), 4; Marinus, Life of Proclus, 10; 26.

- Simplicius, epilogue on commentary on Enchiridion, quoted in Cameron (1969), 14-

- Isidore, quoted in PH,

- PH,

- Agathias, Histories,30.2.

- According to Cameron (1969), 22.

- Stromberg (1946), 176-77.

- Th., 16.10.22 of April 423.

- Geffcken (1978), 228.

- C. Just. 1.1.8.35; i-i.8; 1.1.8.25.

- Just. I.II.IO.

- Just, i.ii.io and i.ii.10.4.

- Just. i.ii.io.1-7.

- Just. 1.11.10.2.

- Gibbon, Decline and. Fall, IV, Chapter 40, 265.

- Athanassiadi (1993), 342-47.

- Shear (1973), 162.

- PH, 43A-C.

- PH,

- Cameron (1969), 17.

- Athanassiadi (1993), 21.

- PH, 36; Olympiodorus in Commentary on the First Alcibiades, quoted in Cameron (1969), 15.

- Marinus, Life of Proclus,

- Vultures: Marinus, Life of Proclus, 15; PH, 117C; “the tyrant” is in Olympiodorus, Commentary on the First Alcibiades, quoted in Cameron (1969), 15.

- PH,

- Plato more dangerous: Chadwick (1966), uff.; Cameron (1969), 9; see also Wilson (1970), 71.

- PH,

- Photius, The Bibliotheca,7-12, quoted in Watts (2006).

- Just. i.n.10.2.

- Cameron (1969), 18, to whose observations these paragraphs are much indebted; Cameron (2016), 222.

- Simplicius in Cameron (1969), 21.

- PH,

- PH,

- PH, 119C and 121.

- Homer, The Iliad,2-5.

- Agathias, Histories,28-2.31.2.

- Agathias, Histories, 30-31.2.

- Agathias, Histories,31.2-4.

- Cameron (1969/1970), 176.

- Al Mas’udi, Les prairies d’or(ed. and tr. B. de Meynard, P. de Courtelle, C. Pellat), ii 741, 278, quoted in Athanassiadi (1993), 28.

- Damascius, ed. Athanassiadi (1999), caption to Plate III

https://beezone.com/nixey/early-christianity.html