America Becomes Aware of “Magic Mushrooms”

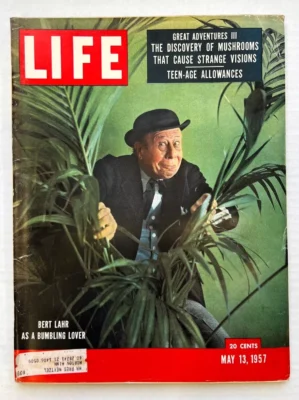

Life Magazine, 1957 – Gordon Wasson

In the May 13, 1957 issue of Life magazine, R. Gordon Wasson revealed the discovery of the sacred mushroom cult of Mexico. His article, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” depicted several species of hallucinogenic mushrooms, and described the modern cult and its history. The title, chosen by the editors of Life, caught the popular fancy, and psilocybin fungi were known thenceforth as ‘magic mushrooms.’ Wasson timed the publication of his article to coincide with the release of Mushrooms, Russia, and History, which he co-authored with his wife Valentina A BRIEF HISTORY OF HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS. This magnificent two-volume limited edition of 512 copies detailed 30 years of study of the field the Wassons named ‘ethnomycology.’

Starting with an arduous study of European mushroom names, the Wassons’ astonishing odyssey had led them to the rediscovery of the sacred mushrooms of Mexico. In this remarkable book, they presented their initial observations on the modern cult of teonandcatl, and included a thorough review of its history. With precision and perspicacity, in moving language, Gordon Wasson reverently described the effects of the mushrooms and the significance of his discovery. As befits a great book, Mushrooms, Russia and History became an instant classic, and has sold for up to $1750 at auction.

The Wassons had found the last dying remains of a once mighty cult. In only a few remote areas of Mexico did the mushrooms continue to hold sway over the Indians. In every case where ritual use of the mushrooms was encountered, the beliefs surrounding the cult were mingled inextricably with Christian concepts. The mushrooms were personified as Jesus, and rites were celebrated before crude wooden altars bearing icons representing the baptism in Jordan and Santo Nino de Atocha (a Catholic conception of the young Jesus).

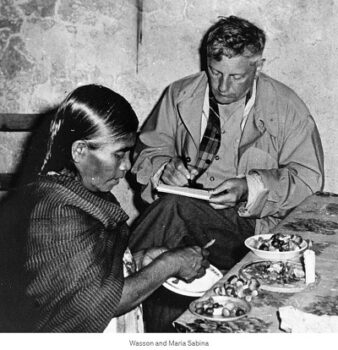

Soon after the publication of the Life article, outsiders, in search of the mushroom experience, began to make the pilgrimage to Huautla de Jimenez. Maria Sabina became the high priestess of a modern mushroom cult born, like the Phoenix, from the ashes of its predecessor (11,48). In Huautla and other villages, the mushrooms were profaned, reduced merely to articles of the tourist trade. Postcards depicting mushrooms, clothes embroidered with mushroom motifs, and the mushrooms themselves were widely and conspicuously sold (46,47). The transformation of the mushrooms to articles of commerce virtually destroyed the remains of the ancient cult. Self-styled shamans staged spurious mushroom ceremonies for the benefit of the tourists. Maria Sabina herself pronounced a fitting epitaph to the secret cult she had divulged to the world: “Before Wasson, I felt that the mushrooms

exalted me. Now I no longer feel this …. From the moment the strangers arrived … the mushrooms lost their purity. They lost their power, they decomposed. From that moment on they no longer worked.”

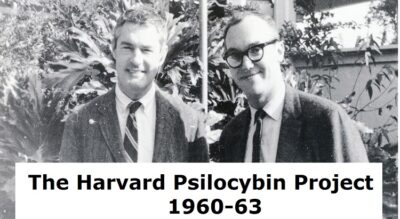

A young psychologist named Timothy Leary learned of Wasson’s discovery and journeyed to Mexico to ingest the mushrooms. In 1960, he had his first psychedelic experience with mushrooms in Cuernavaca (35). Like Wasson, Leary found the effects of the mushrooms to be a revelation, and he eagerly began his own investigations. Leary obtained a supply of synthetic psilocybin from Sandoz Laboratories and began. his now mfamous experiments at Harvard which led to his dismissal from the faculty amid a storm of controversy.

Taken from: TEONANACATL – HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS OF NORTH AMERICA. Edited by Jonathan Ott and Jeremy Bigwood.

The article

It was only a few years later did the American public learned of the revelation of the sacred mushroom ceremony when Gordon Wasson and photographer Allan Richardson revealed a June 1955 velada or sacred mushroom ceremony led by Maria Sabina in a Life magazine article in 1957. They had participated in the ritual themselves. Mr. Wasson was inspired by the fantastic effects and concluded that humans exploring foods in ancient times would have encountered the mushrooms and that the impact “could only have been profound, a detonator to new ideas.” He wrote that when Cortez conquered Mexico, his followers noticed the Aztecs eating mushrooms in a religious setting and calling them God’s flesh or teonanacatl. He described art works in the region going back to a thousand years earlier, such as mushroom stones in Guatemala. In addition to Central American mushroom stones 1000 years old, the ceremonial use of psilocybin mushrooms is apparently depicted on the Aztec Prince of flowers, a seated divine male figure, carved in stone during the 1500s, with stylized mushrooms on its body, along with tobacco, ololiuqui, the hallucinogenic morning glory flower.

Gordon and Valentina Wasson continued to travel to Mexico, and in 1956, Roger Heim, the director of the French Museum of Natural History and a leading researcher on mycology, traveled with them. After Tina Wasson’s death in 1958, Dr. Heim returned with Gordon Wasson in 1959 and 1961, and in 1962, Albert Hofmann and his wife Anita traveled there. A 1958 recording with translations from the Mazatec language, released as Maria Sabina and her Mazatec Mushroom Velada, was his proudest accomplishment among many discoveries. An excellent source about these discoveries is The Sacred Mushroom Seeker, (1990), a series of essays about Gordon Wasson edited by Thomas Redlinger.

Read

THE HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS OF MEXICO:

AN ADVENTURE IN ETHNOMYCOLOGICAL EXPLORATION

Gordon Wasson

Presented at a meeting of the Division of Mycology on January 23, 1959.

Wasson – Adventure in Ethnomycological Exploration

This paper, illustrated with slides, was presented at a meeting of the Division on January 23, 1959,

*”Ethnomycology” was e word coined by us, after the analogy of ethnobotany, to signify the role played by mushrooms in the history of human cultures. It first appeared in print in 1954 in an invitation sent out by the American Geographical Society, New York, N.Y., to a lecture that we were to give before that body.

DIVISION OF MYCOLOGY

THE HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS OF MEXICO:

AN ADVENTURE IN ETHNOMYCOLOGICAL EXPLORATION

Gordon Wasson

New York, N. Y.

Our inquiries into the hallucinogenic mushrooms, after six years and more of research, are now at the end of their first phase.

In Paris, a book on our mushrooms has just been published by the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle. Handsomely illustrated, it deals with every aspect of this strange mushroom complex-anthropological, linguistic, historical, archeological, mycological, chemical, psychological, and religious – and even the initial steps in the therapeutic use of the active agent in the mushrooms. Roger Heim, director of the museum, is the author, and he has done me the signal honor of joining my name to his on the title page. On January 29, 1959, an exhibition illustrating our mushrooms and our experiences with them opened in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, N. Y., to which the Paris Museum has generously lent its collaboration. Thus publication of this paper offers a timely and welcome opportunity to report on our remarkable adventure in ethnomycology. t

It was in September 1952 that my late wife and I first learned of the existence of a mushroom cult among the Indian tribes of southern Mexico. Immediately we undertook, in our spare time, to learn all that had been published about it. There were only three modern papers on this cult that contributed helpful information. However, in the old writings about Mexico, dating mostly from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, we found a number of references to it, all of them of absorbing interest to us. We undertook to make an anthology of these quotations, upwards of a score of them, some of them existing only in manuscripts of the time. We were helped in this search for the sources by kind friends, notably by those eminent authorities on ancient Mexico, Robert J. \Veitlaner and his daughter, Irmgard Weitlaner-J ohnson, We analyzed these quotations, pinpointing on the map of Mexico the places to which they referred, collating the descriptions of the fungi, and scrutinizing what was said about the use of the mushrooms. We undertook to peruse the archeological record in Mesa-America; and what an extraordinarily complex, rich, and enigmatic record it is! \Ve believe that we have discovered, for the first time, our sacred mushrooms in that record. In our forthcoming book we publish the text of all our auotations, and we submit the archeological evidence for the mushroom cult to the judgment of those qualified in this thorny field of recondite learning.

Here a number of questions will occur to the mycologist. What mushroom or mushrooms are worshipped? Many of the old writers speak of the visions that these fungi cause. Do they really produce visions? If so, what is the active agent in them that provokes such a response? What is its molecular structure? Could it be used in therapeutics?

Then there is the anthropological problem. What were the geographical limits of the cult in the old days and where does it survive now, if at all? What role does the mushroom play in the lives of the lndians? The cult lingers in the areas where it existed earlier, in the uplands of southern Mexico, roughly from the latitude of Mexico City to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. It survives feebly if at all in the cities and surrounding country, but in full vigor off the highways, in Indian villages where the native languages are still in current use. In these remote places the sacred mushroom holds t:·,e entire population in its grip. The anthropologists have overlooked it simply because they have not asked about it and the Indians do not volunteer to talk about it.

Not all anthropologists are temperamentally suited for studying such a phenomenon as the mushroom rite among the primitive Indians of Mexico. The anthropological discipline schools its neophytes in a respect for hard, down-to-earth facts. These students are prepared to arrive at the systems of kinship and marriage among the peoples they study, the rules of land tenure and exploitation, the methods of manufacture of textiles and other artifacts, the customs governing the exchange of goods, the calendar systems, and the native cosmologic and eschatological ideas. By the nature of the archeological discipline, there is a natural selection of persons who are not poets, not mystics, not skilled in assessing subjective emotions. Yet in primitive man the poetic element, the religious feeling, exists, and it richly deserves the attention of the modern world. The difference I speak of is the difference between the beauty of a bird in flight and the taxonomist’s description of that same bird’s flight muscles, between the breathless beauty of a rainbow and the physicist’s spectrum analysis of that same rainbow. The divine mushroom that causes the eater to see visions plays perforce a vital role in the inner life of the Indian, that aspect of his life which he i’s reluctant to discuss with strangers of another race and language, and doubly so if those strangers would not enter into the experience sympathetically. The anthropologist who explores these subjects should possess the soul of a poet and the tact of a father confessor, yet he must not let his own imagination run away with him. He must observe, with the eye of a poet, the role of the mushroom in a primitive culture far removed from his own and confine himself to that function. His task resembles the problem of a translator of poetry, who must possess poetic feeling and yet harness his own Pegasus to another man’s imagination. How seldom do we meet with a good translation of poetry! So it is, I feel, with the anthropologist’s study of the subjective religious life of the Mexican Indian. Trained from the beginning to an austere respect for nuggets of fact, most anthropologists – not all – are ill-prepared to enter into the poetic world of the subjective life of the people they are studying, for exploring the world revealed by the sacred mushroom. We at least are alive to the problem. In our writings about the mushroom cult we have tried to escape the Scylla of dry factualism and also the Charybdis of unbridled imagination,

Each year since 1953 we have made expeditions to southern Mexico, to the remote mountain fastnesses where the mushroom cult survives, traveling intentionally in the rainy season, by mule over mountain trails, often in the rain, to live in the Indian villages where the Spanish language is known only to a few headmen. Our first and essential task was to win the confidence of the Indians. Their initial reaction to our presence was always reserved, occasionally hostile: the Indians have had contact with white men for centuries, and we are not viewed with the favor one should like. Our attitude was that of humble suppliants coming to learn the secrets of the sacred mushroom for the benefit of our own people. After an interval the Indians met us more than halfway.

From the beginning we had three objectives: (1) to obtain some of the sacred mushrooms; (2) to attend the ceremony in which they are eaten; and (3) to share in the eating. We were intent on learning everything about the cult: how and when the mushrooms are gathered; how they change hands and reach the ultimate con·sumer, the Indian (and Spanish, if any) names for the mushrooms; the meaning of those names; the manner of performing the ceremony in the different tribes ‘3.lld villages; the purpose of the ceremony; whether the mushrooms are really psychotropic; what one experiences on eating them; and the dosage. We were eager to get photographs and tape recordings of the ceremony, to study the words linguistically and religiously, to identify the mushrooms, to isolate the active agent (if any), to describe this agent’s molecular structure, to define its properties, and, finally, to place our mushroom cult in the context of what is known of primitive religious behavior. A little mor e than six years have passed since we began to devote our spare time to this avocation, and we have now attained all these objectives in some degree.

The identification of our mushroom’s proved much more complicated and exciting than we had imagined. The old writers had given inadequate descriptions of these fungi, but what they said indicated that there were several species. (After all, who can blame those authors for their inadequacies, since the science of mycology had not yet been born?)

Although we expected to find several species, our discoveries went far beyond this, Each region that we visited makes use of species peculiar to itself, only a few species turning up in more than one region. The sacred mushrooms of Mexico belong, for the most part, to the genus Psilocybe and, except for one or two species, they are new to science. Genuinely psychotropic and hallucinogenic.

On the periphery of the area where mushrooms are used for divination – two species serve for that purpose that we believe riot to be psychotropic. Their phallic suggestiveness obviously explains their role, In Tenango del Valle the Indians consume Cordyceps capitata in association with hallucinogenic Psilocybe sp. In one comer of the Chinantla the curandera crushes and eats Dictyophora phalloidea to heighten her divinatory powers.

Roger Heim of Paris, our mentor in all matters mycological, has devoted himself to the classification and study of our mushrooms and, in 1956, he joined us in the field. He identified them as Basidiomycetes and, with the aid of his young assistant Roger Cailleux, he succeeded in cultivating almost all of the fourteen species of Mexican hallucina. genie agarics in the Laboratoire de Cryptogamie in Paris, at first in sterile, artificial media, later in compost in hothouses, thus freeing us of our dependence on Mexico for our supply of raw material.

In the Sandoz laboratories of Basel, Switzerland, with material l supplied from Paris, a research team headed by Albert Hofmann and including Heim, A. Brack, and H. Kobel succeeded in large-scale culture of Ps. mexicana, in sterile conditions on artificial media, isolating two distinctive substances. They called one of them psilocybin and the other psilocin, and they reduced psilocybin to a pure white crystalline powder, arrived at its molecular structure, and synthesized this compound.

For our part, my wife and I concentrated our attention on the anthropological side of the mushroom cult. In the remote Indian villages the Indians regard the psychotropic mushrooms as holy. They fear and adore them. Although the mushrooms are nowhere any longer called by the Aztec term teo-nanacatl, “God’s flesh,” the Indians regard them as the key to communication with the Deity. The mushrooms today are eaten behind closed doors, in the silence and darkness of the night. They do not change hands in the marketplace for money, but are delivered privately, carefully wrapped up, perhaps in a banana leaf. The Indians do not discuss the sacred mushrooms in gatherings: you learn about them talking in a whisper with a friend who trusts you; preferably at night. Es muy delicado, it is very perilous, the Indians say, not to be. taken lightly, and only as a sacrament. There is nothing in common, absolutely nothing, between these sacred mushrooms and our use of alcohol. The vulgar jocularity with which fully civilized peoples sometimes talk of a “binge” or a “jag” is alien to the Indian with his mushrooms. The effects are wholly different. With the mushrooms there. is no hang-over, no obfuscation of the memory, and it seems that one does not, become addicted to the mushrooms as on sometimes does to alcohol and certain other drugs. The dosage remains the same throughout life. The mushrooms are taken when a grave problem needs to be resolved and, I believe, only then. Perhaps there is illness in the family and the mushroom is consulted to learn whether the patient will live or die. If the verdict is for death, the family does not wait but immediately prepares for the funeral, and the sick person loses the will to live and shortly afterward gives up the ghost. If the verdict is for life, the mushroom will tell what must be done if the patient is to recover. Or, again, if a donkey has been lost or if some money has been stolen, the mushroom is consulted and gives the answers. Among these unlettered folk, speaking languages that are not written, there is often no news of an absent member of the family, perhaps one who has gone as a “wetback” to the United States. Here the mushroom, as a postal service, brings tidings of the absent one, whether he is alive and well, or sick or in jail, or prosperous or poor, or whether he is married and has children.

The method of taking the mushrooms varies, In the Mixe country the mushrooms are consumed privately by the suppliant, with only one friend present, to attend to what might happen and be a witness. In other regions a curandero or healer, who takes the mushrooms and who may serve them to others present, is called in. We know of two quite different rites that the curandero may use. In one of them the mushrooms are superimposed on the ceremony of divination that is common to all MesoAmerica, a much larger area than the mushroom country. In this ceremony the curandero casts kernels of maize, and according to the way they fall reads the answers to the questions that are put to him. Of course, there is much more to the ceremony than that: all the accessories to the rite play their part – hen’s eggs, turkey eggs, guacamaya (macaw) feathers, copal (a resin), cacao beans, tapers of pure beeswax, and amate, or wrappings of bark. These accessories play their role with a precision, a nicety, that are equal to the reverence and care with which a priest handles the holy utensils of the Mass. In the mushroom country the curandero simply adds mushrooms to this customary ceremony to strengthen the divine power within him.

In the alternative ceremony the curandero, having partaken of the divine mushrooms, waits for them to seize hold of him and then chants his supplications to the Almighty to come down and answer the prayers and problems of those present. In this ceremony the curandero is esteemed according to the skill he displays in formulating the appeal s to God. Today, and I dare say throughout the past, there have been curanderos who were frauds, embusteros as they are called, but it has been our privilege to know two who were not, and one of them t Marta Sabina, is a woman of presence, integrity, and intelligence. The curanderos are called of God. That is, one becomes a curandero because, having taken the mushrooms, they tell one to follow that vocation. The curanderos are not organized in a hierarchy: each one practices his calling on his own, like the shamans of Siberia, although they may exchange ideas on occasion with each other. As a class, they are shy, usually living apart on the outskirts of town. It would be well worthwhile, before the tradition is lost, to explore all the villages where the sacred mushroom is consulted, to seek out the most proficient curanderos, win their confidence, and explore the recesses of their minds. These agents are the surviving repositories of the Old Religion. I am certain that they would surprise you by the content of their minds and their virtuosity in the discharge of their office.

The sacred mushrooms of Mexico seize hold of you with irresistible power. They lead to a temporary schizophrenia, or pseudo schizophrenia, in which your body lies, heavy as lead, on the petate, or mat, and you take notes and compare experiences with your neighbor, while your soul flies off to the ends of the world and, indeed, to other planes of existence. The musbrooms take effect differently with different persorrs. For example, some seem to experience only a divine euphoria, which may translate itself into uncontrollable laughter. In my case I experienced hallucinations. What I was seeing was more clearly seen than anything I had seen before. At last I was seeing with the eye of the soul, not through the coarse lenses of my natural eyes. Moreover, what I was seeing was impregnated with weighty meaning, I was awe-struck. My visions, which never repeated themselves, were of nothing seen in this world: no motor cars, no cities with skyscrapers, no jet engines. All my visions possessed a pristine quality: when I saw choir stalls in a Renaissance cathedral, they were not black with age and incense, but as though they had just come, fresh carved, from the hand of the Master. The palaces, gardens, seascapes, and mountains that I saw had that aspect of newness, of fresh beauty, that occasionally comes to all of us in a flash. I saw few persons, and then usually at a great distance, but once I saw a human figure near at hand, a woman larger than normal, staring out over a twilight sea from her cabin on the shore. It is a curious sensation: with the speed of thought you are translated wherever you desire to be, and you are there, a disembodied eye, poised in space, seeing, not seen, invisible, incorporeal.

I have placed stress on the visual hallucinations, but all the senses are equally affected, and the human organism as a whole is lifted to a plane of intense experience. A drink of water, a puff of the cigarette, is transformed, leaving you breathless with wonder and delight. The emotions and intellect are similarly stepped up. Your whole being is aquiver with life.

Our friends of Sandoz are offering this active agent for experimentation on the inmates of our hospitals for the emotionally disturbed in Paris and in Lexington, Ky. Will no one try it out on the exceptionally gifted? There is the possibility – I say no more than the possibility – that their powers will be sharpened and they will command insights not given to them in their normal existence.

While we were seeing our visions in the blackness of a tropical night, with the rain pouring outside, the curandera was giving voice to her canticles, invoking the deity to come down among us. She and her daughter took turns at singing. At times she would rise and engage in a complicated clapping, slapping, whacking of different parts of her body, with different resonance depending upon the part of her body that she would strike, with a complicated timing of the whacks, the blows being nicely modulated, sometimes struck lightly, sometimes with full power; and she would rotate to the cardinal points of the compass as she performed. There we were, in a humble Indian hut, with our visions and the authoritative voice of the daughter’s singing in our ears, and the percussive blows of the mother displaying a ventriloquistic virtue, now here, now there, near at hand, far away, as though we were afloat in space, stroked by breezes, listening to the voice raised in song, and surrounded by the calls of eerie creatures darting around us.

The performance of the curandera reaches a climax every twenty or thirty minutes. Then suddenly the singing stops and the mushroom speaks. She whips out the words of the oracle, loud, sharp, with compelling authority, the syllables cutting the night air and the darkness and the silence like a knife. Afterward everyone relaxes, cigarettes are lighted, and there is general conversation in which the curandera participates.

After four or five hours of this experience we would all fall into a deep slumber, from which we would awaken some two hours later, refreshed and ready for work-ready, that is, except that the cleal recollection of our adventure made work seem unimportant, and the important thing to do was to compare notes with our companions and record in our diary every detail of the night’s events.

I have now told you what we have accomplished, in the field and the laboratory, in the past six years. We have rediscovered the sacred mushrooms of Mexico, identified them, isolated the active agent, and proceeded to the determination of its properties. What is there for us to do now? Our field of research widens as we progress. Let me outline, what seems to me, in the anthropological field, the course to pursue. Remember that all I shall say is speculative, awaiting confirmation.

We are dealing here with an authentic form of the religion of primitive men. Let me repeat what I said before: that it would be an error to bracket the hallucinogenic mushrooms with alcohol, as just another drug that serves as an escape for man. The mushroom, despite its potency, is a dying agent. In the primitive world its survival is spotty, although there is evidence that its use was widespread long ago. It survives only in peripheral cultures, among the most isolated and neglected peoples, in Siberia, in Borneo, in New Guinea, until recently in Peru, and in Mexico. At an early stage in the evolution of a culture, it serves as the great mediator with God for peoples who are just beginning to be familiar with the idea of God.

The animal kingdom does not know God; it has no conception of the religious idea. The animal cannot imagine horizons beyond the horizon it has actually seen, a past earlier than it has experienced, a future beyond the immediate future, planes of existence other than this one in which we find ourselves, There must have come a time when man, emerging from his bestial past, first grasped these possibilities, vaguely, hesitantly; when he first knew the awe that goes with the idea of God. Perhaps these ideas came to him unaided, by the light of his dawning intelligence. I suggest to you that, as our most primitive ancestors foraged for their food, they must have come upon our psychotropic mushrooms, or perhaps other plants possessing the same property, and eaten them, and known the miracle of awe in the presence of God. This discovery must have been made on many occasions, far apart in time and space. It must have been a mighty springboard for primitive man’s imagination. The secret of the miraculous discovery would be closely guarded, and it would leave little trace, other than by ricochet in folklore, in legend, and in the etymology of relevant words. From the beginning of history there have been seers, mystics, prophets, and poets who have seemed to possess the secret vision of eternal values. They achieved this by fasting and other ascetic practices or, perhaps, as in the case of Blake and Keats, by their abnormal sensitivity. Blake’s description of the poetic gift is singularly apt for the experience of the mushroom agape: “He who does not imagine in a stronger and better light than his perishing mortal eye can see, does not imagine at all.” The divine mushroom would open up the world of visions to far greater numbers, and the kingdom of God would be within reach of everyone who possessed the sacred secret. The Kingdom of God would be within you.

The ceremony we attended in southern Mexico was a true agape, a love-feast, a Holy Supper, in which we all felt the presence of God, in which the Element carried its own conviction in the miracles it performed within us. The faithful were not obliged to accept the dogma of Transubstantiation in order to know that they had partaken of the body of Christ. (How startling it is that the ancient Aztecs called this Element by the same name that we use for the Bread and Wine of the Eucharist-God’s Flesh!) May not the sacred mushroom, or some other natural hallucinogen, have been the original element in all the Holy Suppers of the world, being gradually replaced by harmless elements in a watering down of the original fearful sacrament? May this not be the explanation of the Archetypes, the Ideas, of Plato? The ancient Greeks never revealed the secret of the Eleusinian mysteries, yet many must have known it and whispered to each other about it. We know only that the initiates drank a potion and later in the night knew a great vision. The Greeks, who were the fathers of pure reason, reserved a portion of their minds for the mystical element, the mysteries of Eleusis, the oracle at Delphi, the daemon of Socrates. No one knows for sure what beverage the ancient Hindus meant by the Soma, nor what was the origin of the ling chih of the Chinese, the divine mushroom of immortality. Here is a missing element in our knowledge of these cultures, one that possibly can now be identified by the methods that we have used in our quest of the sacred mushroom.

There remains one question that some may be asking themselves, and that I gladly answer. How is it that I, a banker, and my wife, a pediatrician, have gone into these remote territories, and how does it come about that I write about these subjects? Our mushrooms impinge on a multitude of disciplines: in science, on mycology, chemistry, psychology, and medicine, in the humanities, on folklore and mythology, philology, anthropology, archeology, history, and religion. How does it come about that laymen without academic qualifications in any of these disciplines are so bold as to address a scientific body on these subjects?

My wife and I began to gather our material long ago, in 1927, on an August afternoon in the Catskills, as we strolled along a mountain path on the edge of a forest. She was of Russian birth and I am of AngloSaxon ancestry. I knew nothing of mushrooms and cared less. They were for me rather repellent and, like as not, deadly poisonous. In the years that we had known each other, I had never discussed mushrooms with my wife. Suddenly she darted away from my side: she had seen a forest floor carpeted with mushrooms of many kinds. She knelt before them, called them by endearing Russian names, and over my protests insisted on gathering them in her dress and taking them back to our lodge, where she went so far as to cook them and eat them-alone. My wife adored mushrooms, though she had never studied them or possessed a book about them. What she knew about them she had picked up at her mother’s knee. The Great Russians experience a love for mushrooms that passes belief, that borders on the abnormal, just as we Anglo•Saxons are abnormally afraid of them.

This episode made so deep an impression on us that from then on, as circumstances permitted, we gathered all the information that we could about the attitude of various peoples toward mushrooms-what kinds they know, their names for them, the etymology of those names, the folklore and legends in which mushrooms figure, references to them in proverbs and literature and mythology. We were interested in what untutored folk knew about mushrooms, those who had never seen a book on the subject, but knew only what had come down by oral tradition from their ancestors. Like stout Cortez, awed by the spectacle of the Pacific from his peak in Darien, we found we were privileged to tread a virgin field ripe for exploration.