The following article was originally published in Laughing Man magazine, Vol 5, NO 1, November 1, 1984. Beezone updated this article in November 2020.

Kenneth Pelletier, Ph.D.,

Dr. Pelletier is a Clinical Professor of Medicine, Dept of Medicine; Dept of Family and Community Medicine; and Dept of Psychiatry at the University of California School of Medicine (UCSF) in San Francisco. At UCSF Med, he is the Director of the Corporate Health Improvement Program (CHIP) a collaborative research program between CHIP and fifteen Fortune 500 corporations including Ford, Oracle, Prudential, Dow, Lockheed Martin, NASA, Pepsico, IBM, Cummins, Steelcase, and the Mayo Clinic. He is also Chairman of the AHA and a Vice President with American Specialty Health (ASH).

Dr. Pelletier is a medical and business consultant to the USDHHS, the WHO, the NBGH, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and major corporations including Cisco, IBM, American Airlines, Prudential, Dow, Disney, Ford, Mercer, Merck, Pepsico, Ford, Pfizer, Walgreens, NASA, Microsoft ENCARTA, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, United Healthcare, Health Net, the Pasteur Institute of Lille, France, the Alpha Group of Mexico, and the Singapore Ministry of Health.

He has or currently serves serves on the boards of Rancho la Puerta (Mexico), Fries Foundation, American Institute of Stress (AIS), American Journal of Health Promotion (AJHP), is a Founding Board Member of the American Board of Integrative Medicine (ABOIM), and as a peer reviewer for the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (JOEM), Annals of Internal Medicine, Health Affairs, and webMD.

He has been recognized in numerous appearances on ABC World News, the Today program, Good Morning America, the CBS Evening News, 48 Hours, the McNeil-Lehrer Newshour, CNN, FOX News, CBS Sunday Morning, Hour Magazine, the Time/Life video series, an award winning BBC series, and a Blue Cross/Blue Shield sponsored PBS series.

Dr. Pelletier is the author of the international bestseller Mind as Healer, Mind as Slayer (translated in 11 languages); Holistic Medicine; Healthy People in Unhealthy Places; Sound Mind – Sound Body; The Best Alternative Medicine; Stress-Free for Good; New Medicine and Change Your Genes – Change Your Life (2018).

Charles Seage, M. D„ and Fred Rohe, editor of THE LAUGHING MAN, interviewed Dr. Pelletier at his San Francisco office (1984). Delightfully approachable, he was vibrant, open, witty, and. as befits an expert on longevity and holistic health, fit, and youthful.

THE LAUGHING MAN: You referred in your book Longevity: Fulfilling Our Biological Potential to a study by some Dutch cardiologists for the University of Amsterdam, focusing on one hundred people over the age of 90. Your summary statement was, “A life of hard work without the hazards of affluence is typical of people who live to a healthy old age.” What are the hazards of affluence?

The American Institute of Stress

DR. Pelletier: It surprised me. but one of the major observations coming from visiting people from long-lived cultures was that by our standards they are deprived. They are poor and live what looks to us like a hard life. They have been spared a refined, high-fat, high-sugar diet. They have been spared the kind of excessive stress we have come to associate with being normal and the kind of alienation represented by not even knowing who our neighbors are.

The people in the Dutch study were all survivors of World War II. That was a time of extreme stress. But it was stress of a clear-cut. unambiguous nature. You might get blown up—nothing subtle about it. That is what I call “type 1” stress—immediate, identifiable, resolvable. Our bodies are meant to handle type 1 stress, then just let it go. “Type 2” stress is the ambiguous kind—worry, anxiety, and that sort of free-floating sense of aggression we find around us. That is the most destructive form of stress, keeping people uptight. I think that is the major hazard of affluence that long-lived people are spared.

THE LAUGHING MAN: What are some of the long-lived cultures you have studied?

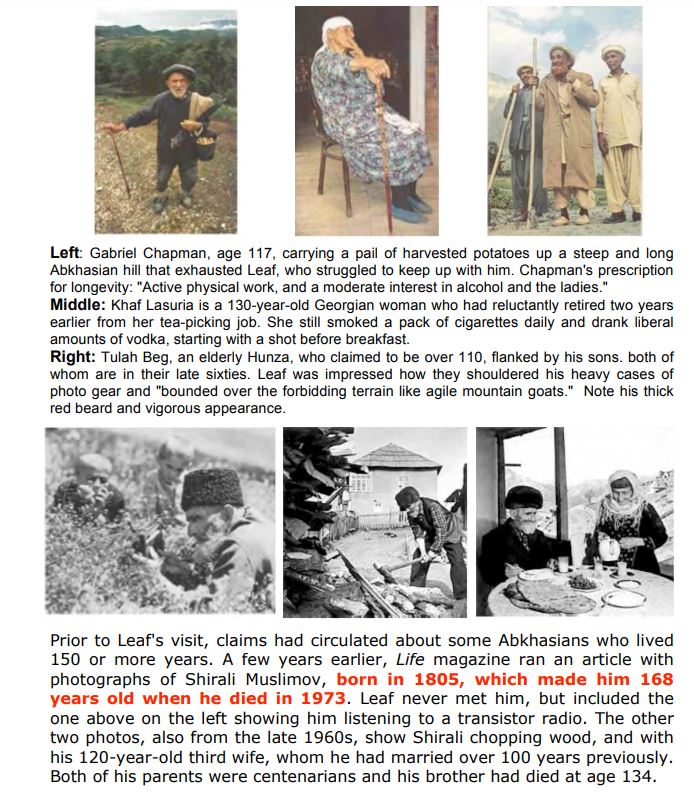

DR. PELLETIER: The Vilcabamba in the Ecuadorian Andes, the Hunza in the Himalayas of northern Pakistan, the Abkhazanians in the Caucasus Mountains in the Soviet Union, the Mabaans of Sudan, and the Tarahumara Indians in the Sierra Madre mountains of northern Mexico.

I started out, in part, to discover whether or not these reports about long-lived people were verifiable. I became quite convinced that they are true to some degree, though not to the extreme ages like 200. But there are enough cases in the 115 to 130 range to really take seriously. Correlating evidence from laboratory research overwhelmingly supports those ages as our real potential. In fact, there is virtually no evidence to account for the present life expectancy in the mid-70s. All you can say is, that is what the numbers are. There is no adequate theory to explain why we last only that long. We are built to last much longer.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In his book, The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace, Spiritual Master Adi Da also says we are built to last much longer than we do, that basically we toxify and degenerate ourselves out of our real potential. Would you agree?

DR. PELLETIER: Yes, I would. People in the long-lived cultures die of degenerative diseases like cancer, too, and have heart attacks. But perhaps cancer and heart disease are normal if you are 110 or 115. On the other hand, we take people dying of degenerative conditions at 45 or 50 to be normal. That is not normal.

THE LAUGHING MAN: It wasn’t even normal in this country fifty years ago.

DR. PELLETIER: Right. It is only “normal” in an unhealthy society which does not fulfill its biological potential.

THE LAUGHING MAN: You said in your book that none of the major theories about aging take any of the other theories into account.

DR. PELLETIER: Yes. It is absolutely astounding. It is probably one of the most fragmented areas of research ever seen. You read the literature on one theory of aging and you don’t find any references to any of the other theories. For my book, I researched all the major approaches. There are seven or eight major theories of why we age and, by extrapolation, how life extension can occur. Every one of them is fixed on a single variable, basically explaining only one aspect of aging and therefore only one aspect of possible life extension. If you just looked at the antioxidant theory, you might, in fact, begin to formulate that so-called life extension kind of diet.

“There is no single factor that produces life extension”

The error is – and I am absolutely certain of this – there is no single factor that produces life extension. It is a combination of factors. There is a genetic predisposition, there are environmental factors, and there is diet too, no question about it. Social support systems are also important, as well as the stress factor— there is a multiplicity of factors. To neglect any factor is like having a recipe in which you leave out one of the major ingredients. The result may not be inedible, but it will definitely not be what you intended. When you leave out one of the major longevity factors, you do not get a slightly diminished effect, you get a greatly diminished effect.

THE LAUGHING MAN: What about all the food supplements recommended by Pearson and Shaw in Life Extension!

DR. PELLETIER: Well, for one thing, if you are talking about an aging person with some diminishing of kidney function, all those supplements may be more than ineffective—they may be dangerous.

For another thing, most of those recommendations are based on one or two experiments done with animals. Now that sort of thing is interesting and can be a source of fruitful speculation. But when you are talking about what you would advise people to do with their lives, you run into some real problems, even ethical problems. I personally would not undertake any dietary regimen based on a couple of animal experiments.

THE LAUGHING MAN: What have you learned about diet in connection with the long-lived cultures?

DR. PELLETIER: Some of the dietary influences on longevity have been known for almost fifty years. In 1938 Clive McKay did a classic study at the University of Michigan. He took two groups of rats, let one group eat whatever it wanted to, and then, calculating their average caloric consumption, allowed the second group to eat only half as much. The free- feeding rats averaged about 18 months life span while the restricted rats averaged between 26 and 28 months. Now, that one factor—called “prolonged caloric restriction”—is an absolutely unequivocal life-extending factor. We consume generally between 3200 and 3500 calories per day. The long-lived peoples consume between 1800 and 2000 calories per day and are at normal weight or slightly underweight.

They also consume much less protein than we do. We average between 90 and 100 grams of protein per day. They average between 35 and 50. They almost never eat red meat. If they are meat-eaters, they eat predominantly fish and poultry, but these people are primarily lacto-vegetarians. Most of their protein comes from grains, legumes, and dairy products. This seems important because at the higher levels of protein consumption you get elevated levels of serum cholesterol, loss of calcium from the bones, and you increase the risk of coronary disease. Contrasted with us, those peoples have much lower cholesterol levels, virtually no osteoporosis [decalcification of the bones], and much less coronary disease.

Another factor that seems likely to me—one that has not been adequately researched yet—is that these people have much more naturally-occurring antioxidants in their food. That would be vitamin E from their whole grains and selenium coming from food growing in mineral-rich soil with a lot of organic matter in it.

Another area of research has to do with the genetic diversity of the food crops. If you look at a field of wheat in Kansas, it is absolutely uniform. That is because of genetic selection for uniformly high yields. But if you look at a field of wheat in the Caucasus region of Russia, you see different colors and sizes of plants—yellows, grays, reds, some of it kind of scruffy. The important difference is, though, that our wheat baked into a loaf of bread provides incomplete protein, whereas their genetically diverse wheat has amino acids that combine into complete protein—the real staff of life.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Would you comment on something Master Da Free John has said about aging in The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace”! Speaking about certain yogic techniques aimed at prolonging life, he says, “In sheerly physical terms one can in fact lengthen one’s life through such practices. But from a spiritual point of view, such goal-oriented activities are not appropriate. It is in the natural process of relational living that longevity is spontaneously attained. Longevity is natural in the case of one who lives constantly in God-Communion via physical activity, via the breath, and via higher conscious participation in Life and living relationships.”

DR. PELLETIER: Then there is exercise. There is excellent research that shows much greater life expectancy for people who engage in moderate aerobic activity with some sort of yogic activity, maintaining both cardiovascular fitness and flexibility. All the cultures with a high percentage of centenarians have this dimension of active physical involvement throughout life.

Looking at the breath principle, every yogic and meditational discipline points to the importance of breathing. And one of the best independent measures of aging is the diminishment of breathing capacity. One of the highly predictive factors for longevity is respiratory capacity—literally called “vital” capacity. If it is maintained over the years, the person is likely to live a long life.

Where the relational factor is concerned, the Alameda County [California] Study comes to mind as a good example. A large study group, seven thousand people, was followed for nine years. What they found is that women who did not have a social support group or a friend or even a pet or a plant had a death rate three times higher than those who did. For men in those circumstances, the mortality rate was over twice as high as for men who had those kinds of relationships.

So, taken together, those three factors make, as I said, a very profound statement.

DR. PELLETIER: None of the cultures of long-lived people set up their way of life as a way to achieve longevity. They start out to live a high quality of life, one that is fulfilling, that has more than a material purpose. They believe in higher states of consciousness beyond everyday reality and they have a well-developed sense of an afterlife.

THE LAUGHING MAN: From the scientific point of view, how does having familiarity with higher states of consciousness and a sense of an afterlife actually affect the human organism to produce longevity?

DR. PELLETIER: Well, we may have negative evidence of what happens in their absence. There is a classical clinical description called the Helpless-Hopeless Syndrome in which people deteriorate very rapidly. This is the case when people have given up, lost the will to live.

When you contrast depression— which is a characteristic of helplessness and hopelessness—with humor or laughter, you discover distinct biochemical differences in the body. As an example, under depression all of the catabolic, or destructive, biochemical changes predominate in the body. That means tissue is torn down, sugar is metabolized, food substances are broken up to get energy. When we are happy, humorous, optimistic, the anabolic functions predominate—all the building up, energy functions. If you look at one as being destructive in the long run and the other as being constructive in the long run, I think you do have the difference between death and disability on the one hand and health and life on the other. None of this answers your question directly, of course, but the inferences are available.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Have you synthesized what might be called a “longevity recipe” as a result of your work in the field?

Dr. Pelletier: There is no recipe for longevity. You could put together a checklist of longevity factors and follow it closely and perhaps decrease some of your likelihood of illness, but you would have no guarantee of any significant effect of life extension. The story I like to illustrate this is about Charlie Smith, a black man who died about two years ago at the age of 136. He was one of the oldest documented individuals in the world, and he was interviewed when he was 134.

The interviewer said, “How were you able to live so long?” And Charlie said, “Well, I smoked and I drank and I chased women and I stayed out late.” The interviewer, a little aghast, said, “But you are 134!” And Charlie replied, “Yes, if I knew I was going to live this long I would have taken better care of myself.”

The Laughing Man: That is reminiscent of something Dr. Roger Williams said. Speaking about predictors of longevity, he observed that you will get one centenarian who says that he owes his long life to never having drunk or smoked. Then you talk to another one and he says he owes being 110 to the fact that he made sure he had a drink of whiskey and a cigar every day.

DR. PELLETIER (laughing): Exactly! One of the things I did in my book was to make a list of all the subjective statements people made about how to live to be so old. Some said eat a lot, some said undereat. Some said have a lot of sex, some said have none. There was no consensus at all. The only thing you could say is that people’s statements about their longevity were mutually contradictory.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Is it true in your experience that most people in this society are afraid of old age?

DR. PELLETIER: We tend to have a very negative image of old age in this country: decrepit, depressed, withdrawn, sick, helpless, hopeless. With those sorts of images in mind, people say, “I don’t want any part of living a long time.” But when you study the long-lived cultures, you see nothing like this attitude—for several reasons. First, those same factors that determine the quality of life, that make it enjoyable and worth living, are the factors that have the major influence on the quantity of life. So there is no expectation that a large quantity of life translates into a low quality of life.

Secondly, we tend to be repulsed by images of long, lingering, miserable illnesses leading to death, whereas generally the old people in the long-lived cultures die quite quickly when their time comes. So there is not this dread of the dying process.

Thirdly, the whole psychological dimension of being elderly in these cultures is a positive one. It is an honorable status. The elderly have dignity. They are never made to feel useless. Often the elderly are in charge of child-rearing because the parents are busy working. They usually have a sort of judicial role in family life. So, old age is a powerful, esteemed position one looks forward to. Here, on the other hand, the elderly generally have just been put to pasture— they feel useless, unwanted, unloved. It is hard to imagine a worse psychological environment for being old.

We need to make enormous changes in our mental picture of old age and what it means to be retired. Retirement can’t just be the end of a productive life. It may be time to retrain or educate for a second career. The retired accountant becomes a marine biologist. Perhaps best of all, it can be a time when we turn away from a material orientation, acquisition, making a reputation, towards a more inner-directed orientation or a life of service.

We are just a few years into the field of psychoneuroimmunology, which is a real missing link in all of this from the scientific point of view. We can now measure a whole realm of biochemical changes that are mind-influenced. As examples, we can measure the two- to four-month depression of the immune system that follows the loss of the spouse for the survivor. We have measured the astronauts’ decreased immune response after prolonged space flights, especially immediately after reentry, an extremely high-stress situation. We have begun to detect the destructive biochemical changes that take place under conditions of depression and hopelessness. Ultimately, I think, we will be able to monitor the regenerative capacities associated with these more positive approaches we are talking about.

THE LAUGHING MAN: There is another aspect to the psychology of aging. That is, a person ages according to his or her expectations. My teacher, Master Da Free John refers to “psychological clocks,” which are tacit beliefs regarding how health and vitality are supposed to develop or degenerate according to age. He says, “These clocks are generally an ‘age mythology’ that tends to perpetuate itself from generation to generation. Our habits and conditions of living tend to reflect our psychology and beliefs, and human beings do in fact become, develop, and degenerate in accordance with their subjective clocks. But the ‘clocks’ may be changed, if they are arbitrarily established and negative in effect. Indeed, they must change as we pass from stage to stage of growth and as we operate on new levels of energy and presumption.

“If an individual lives a spiritual life, founded in Truth and love, and practices a vitalizing or regenerative regimen of diet and life-activity in general, then he can change the clocks that are set by conventional beliefs and habitual reactivity. To begin with, he must simply and intelligently release all belief in the old clocks—the assumption of necessary disease and degeneration. And, secondly, he must establish a habit of life that is completely free of degenerative and reactive practices.”

DR. PELLETIER: This is profound. Several examples of psychological clocks come to mind. We structure our lives around having a mandatory midlife crisis. There is some minimum biological basis for it, but if you look cross-culturally, it does not have the magnitude we give it. Then we have created this kind of structure in which 65 is some sort of mandatory aging plateau. After that we believe that in the mid-70s death is likely. These are mostly unconscious ideas that, I believe, function to foreshorten our life expectancy.

There is a fascinating study done in Canada by a woman from Yale University. She took three thousand people at age 65 and gave them a complete battery of medical and psychological assessments to see which of them would be most predictive of their health and vitality at age 70. She found that virtually none of the medical and psychological factors predicted the likelihood of being alive and well at age 70 except for a sort of throwaway question. That question asked them whether they were pessimistic or optimistic about their health and longevity over the next five years. Comparing medically unhealthy but optimistic people with those who were healthy but pessimistic, more of the unhealthy but optimistic people were alive and well at age 70. More of the healthy but pessimistic people had died or become disabled.

Where the spiritual aspect is concerned, if you look at the long-lived cultures you see that they all have a religious or spiritual sense of the world and themselves. There is no identifiable dogma, but all of them believe in a purposeful universe in which they have a feeling of personal purpose, a deep sense of meaning about life.

THE LAUGHING MAN: How would you explain the positive influence of spirituality on longevity?

DR. Pelletier: It is not explainable, but it certainly is observable. It pervades the entire lives of all the long-lived cultures— even in Russia, which is officially atheistic. The people of the Abkhazanian and Georgian regions are still deeply religious, and the old Russian Orthodox Church is very metaphysical, emphasizing the transcendental state.

The spirituality of all these people is not a Saturday afternoon or Sunday morning affair. There is no separation between life and spirituality. They are one and the same. I think that quality has an extremely profound effect on the overall health of these people. They are not merely practicing spirituality in a ritualistic way. Rather, they are living it day by day.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Your book has a list of longevity variables derived from assessing two hundred such variables in a group of two thousand healthy males. One thing surprising about it is that exercise, while high, is only number nine.

DR. PELLETIER: Yes, one might assume it would be second or third. But we have distorted the importance of exercise because we are drawn to what is easily visible. We have made a business out of health and beauty from exercise—always exercising, selling exercise machines, joining clubs, and all the rest of it. Yet, it is probably the last in order of importance of the strongly contributing longevity factors. Look at sense of humor—I think that is number six on the list, which is really fascinating.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Right, what would you say about that?

DR. PELLETIER: To me it is the most striking characteristic of the long-lived peoples. They strike you as being very vital and very joyful. Their humor is childlike, not demeaning, not veiled hostility, not derogatory, not ironic. They really enjoy silly practical jokes, and they have this easy humor about life and about themselves.

Two things always strike me when I come back here. One is the sheer amount of bewildering, frantic activity without a purpose. Second is the total lack of humor. We are not only caught up in all this frantic activity, but we take it all so seriously. These people do not do that. They live a kind of vital, happy life. It is not unusual for them to dance and sing. Everything is a cause for celebration— birthdays, comings and goings—they are frequently celebrating something. They drink quite liberally and that certainly contributes to the overall sense of good humor, although they seldom get drunk and they have virtually no problem with alcoholism, liver dysfunction, or brain damage. I think that is due to the overall vitality and joy they have about their lives.

I find one of the most objectionable things in reading about longevity or life extension is the absence of joy. It is all turned into a set of puritanical prescriptions. Likewise, we turn exercise into a drab regimen instead of a joyful expression of physical energy.

Other than humor, some sort of meditative practice is also a characteristic of long-lived peoples. If all you have is a checklist of superficial longevity factors, you miss the wisdom of a life well and consciously lived.

Further Reading: