For general purposes, there is probably no more serviceable classification of the plant’s man uses in his striving for temporary relief from reality than that proposed by the German Toxicologist, Louis Lewin.

Of Lewin’s five categories, i.e., Excitantia, Inebriantia, Hypontical, Euporica, Phantastica, none has stirred deeper interest through the ages, and none has foretokened a greater field for discovery for the present and future, that the Phantastica. There have recently been proposed very learned and intricate words to distinguish the several kinds of narcotics. Our modern terminology has come to call these the hallucinogens, the psychotomimeties, or the psychedelics.

Taken from lectures given by Richard Evans Schultes, Ph.D. Curator of Economic Botany, Botanical Museum of Harvard University in the Third Lecture Series 1960, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas.

***

“It is fitting and natural that the Harvard intellectual community be the first to grapple with this new philosophic and practical issue and that the University of William James be given the first chance to accept or reject the educational potentialities of consciousness-expanding drugs.”

Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary, Harvard Crimson, 1962

***

Harvard Psilocybin Project 1960-1963

***

“Three years ago, on a sunny afternoon in the garden of a Cuernavaca villa, I ate seven of the so-called “sacred mushrooms” which had been given to me by a scientist from the University of Mexico. During the next five hours, I was whirled through an experience which could be described in many extravagant metaphors but which was above all and without question the deepest religious experience of my life. This discovery left me feeling exhilarated, awed, and quite convinced that I had awakened from a long ontological sleep.

Since my illumination of August, 1960, I have devoted most of my energies to try to understand the revelatory potentialities of the human nervous system and to make these insights available to others.”

Lecture by Timothy Leary delivered at a meeting of Lutheran psychologists and other interested professionals, sponsored by the Board of Theological Education, Lutheran Church in America, in conjunction with the 71st Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Philadelphia, Bellevue Stratford Hotel, August 30,1963

***

“We do not go into ceremony to talk about God. We go into ceremony to talk with God.”

Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Quahadi Comanche people, and the man credited with playing a key role in the peyote movement and the establishment of the Native American Church.

***

The Harvard Psilocybin Program

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert found the Harvard Psilocybin Project in October 1960 after Leary’s experience in Mexico.

BACKGROUND

In the winter of 1959, Leary traveled to Florence, Italy. There he began work on a new manuscript, The Existential Transaction, which summarized his ideas for a new psychology.

He met his old pal Frank Barron who was on sabbatical in Europe and told Leary about an extraordinary experience he had on a study trip in Mexico. A psychiatrist there had given him a small bag of so-called magic mushrooms which had given Barron William Blake revelations, mystical insights, and transcendental perspectives.

Leary was fascinated by Barron’s extravagant report but also concerned about the professional reputation of his old friend. But Barron had even more to report: Professor David McClelland, Director of the Center for Personality Research* at Harvard University was also in Florence at that time and, having read Leary’s The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality, might be able to help him find a new job. The next day, Leary met McClelland and told him about his next book in which he promoted a new existential understanding of the psychotherapeutic process which took the patient, therapist, their environment and world views into account as an interactive system. Such a theory was new to McClelland, but he appeared to like Leary s plans and vision. After a while he said: Okay, I am ready to offer you a job. You re just what we need to shake things up at Harvard.

Soon, other colleagues became interested in researching new methods of behavior change. One young assistant professor in particular stood out: Richard Alpert. He was the son of a wealthy Boston family, had graduated from Stanford University, and had come to Harvard in 1958 as a lecturer in psychology. He was ten years younger than Leary.

The two men were the only faculty members in their department who made themselves available to their students in the evening. Their offices were not far apart, and they soon became friends and decided to start a project together.

Leary thought of Frank Barron, and McClelland agreed to bring him from Berkeley to Harvard and gave the green light for a one-year psychology research project. It was to start in the fall of 1960 which gave Leary, Barron and Alpert an entire summer to leisurely develop their plans.

Barron and Leary drove to Mexico during the semester vacation and rented a magnificent villa with a swimming pool in Cuernavaca. Lying in the sun on beach chairs, they planned to lay out the content, goal, purpose and general framework of their project.

One day, Gerhart Braun, an anthropologist at the University of Mexico, stopped by and told them he had gotten a small bag of psilocybin mushrooms from a curandera which he would gladly share with those guests present. By then, Leary had read about magic mushrooms and, after some hesitation, he decided to try them. They did not taste good to him: The smell was like crumbling logs or certain New England basements. But soon, he began to feel the hallucinogenic effects and everything began to quiver, to come alive (see above description of Leary’s experience).

Harvard seemed to be the ideal university for this even psychologist and philosopher William James, previous lecturer at this elite university and founder of the profession of psychology in the United States, was acquainted with psychedelic experiences.

In 1897 James described his experiments with laughing gas in his essay The Will to Believe. His work The Varieties of Religious Experience made him world famous.

In a short time, Alpert, Barron, and Leary met other students, doctoral candidates, and professors who were willing to assist and volunteer for their unusual project.

In October 1960, they founded the Harvard Psychedelic Research.

Professor McClelland and a few of his colleagues had imagined the project somewhat differently but Harvard was a stronghold of academic freedom so Department Chairman Henry Murray gave the green light to the Harvard Psilocybin Project.

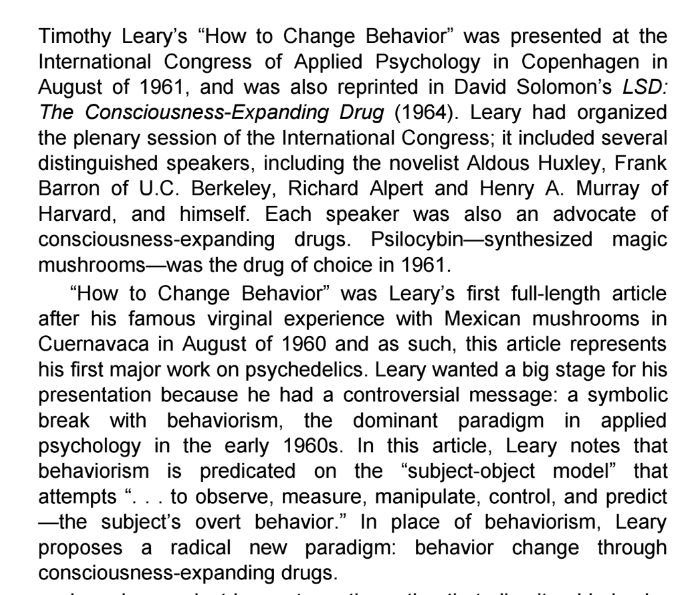

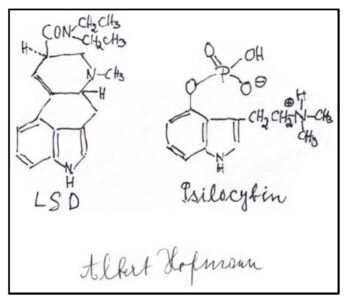

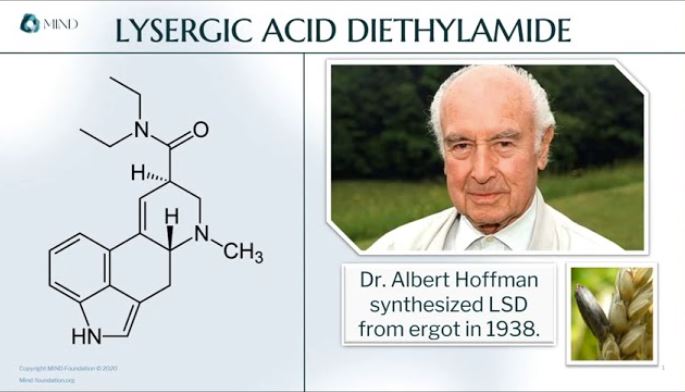

Leary was determined to apply what he had learned to his profession. He had little trouble persuading David McClelland to approve the Harvard Psilocybin Project and soon thereafter he discovered that he could order a substantial quantity of synthetic psilocybin from Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, which was producing the drug under the tutelage of Albert Hofmann — the chemist who had discovered LSD.

The experimental protocol that Leary settled on called for giving subjects psilocybin in a non-clinical setting — in pleasant and spacious surroundings that would be conducive to “pleasant, ecstatic, non-anxious experiences.” The observer was expected to be “collaborative, open and humane,” establishing the best possible mind set for the subject to have a positive experience. (Contrary to general public perception, Leary had already suggested this notion of set and setting during his exploration of therapeutic psychology.) Observers and subjects were to be interchangeable. Everyone participating had to be experienced. The research would be closed to undergraduates.

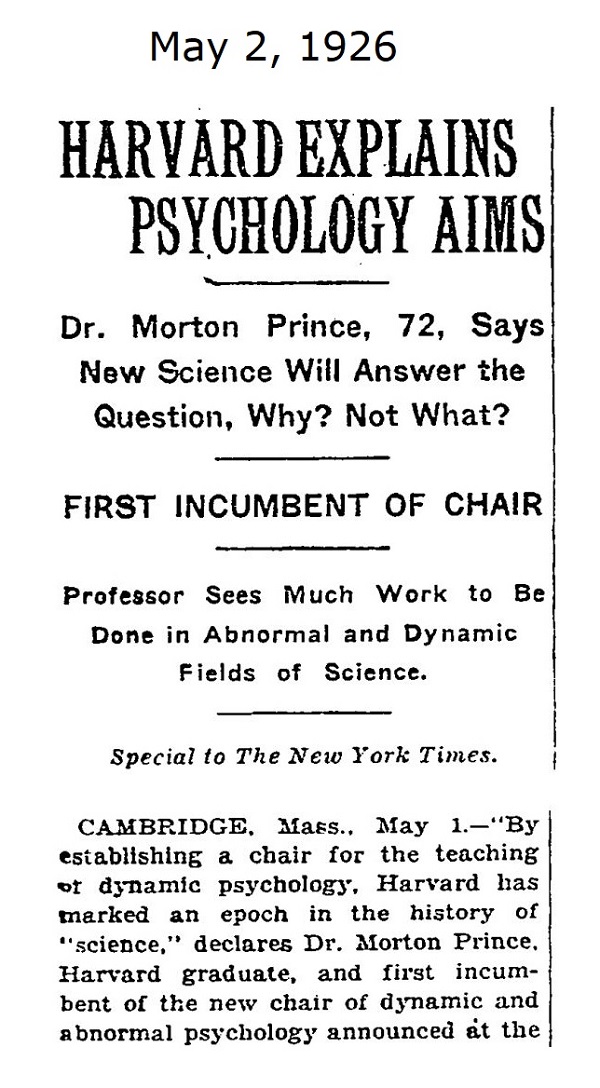

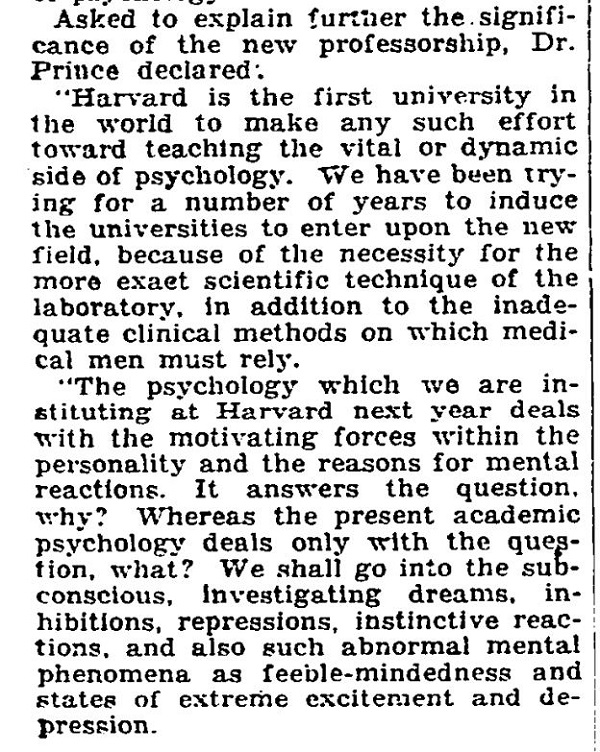

*The Center for Personality Research was formed originally by a grant to Harvard by Morton Prince in 1924 under the name of ‘The Harvard Psychological Clinic. The new clinic was designed for the scientific study of personality. One interesting clause in the endowment was that this new clinic would not be with the Harvard Medical School, where behavioral and psychiatric studies were conducted.

A 1940 edition of The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology describes why. The professional animosity developed in the impassioned climate: “The psychoanalysis are inclined to consider the academic psychologist’s curious fellows in no way concerned with the real problems… Psychologists, on the other hand, are inclined to look on psychoanalysts as `mystics’ or `cultists.”‘

Early Signs

From the beginning, the so-called experimental attitude in mainstream psychology has always rejected the construct of the unconscious as unscientific. Lightner Witmer, for instance, rejected it in the 1890s, John Watson rejected it in 1913, and Skinner rejected it in the 1930s. Meanwhile, erstwhile psychologists tried valiantly to answer this objection, mainly in the field of personality psychology.

In 1935 Harvard psychology professor Henry Murray and his lab assistant Christiana Morgan together published an article on a new test of their devising, the Thematic Apperception Test or TAT, subtitled ‘A method for investigating fantasies’, they were not so much interested in exact measurement as in penetrating efficacy. The test was to be a way of making the invisible visible, the irretrievable retrievable: ‘My idea’, Murray said in a later interview, ‘was to illuminate the unconscious processes – that were repressed – of which the subject was not aware. That was the whole point of it’. They solidified their invention with a 1938 volume from Harvard University Press called The Thematic Apperception Test and reissued the manual in 1943, again with Harvard University Press, by which time the test was a star, a new light in the field of personality psychology.

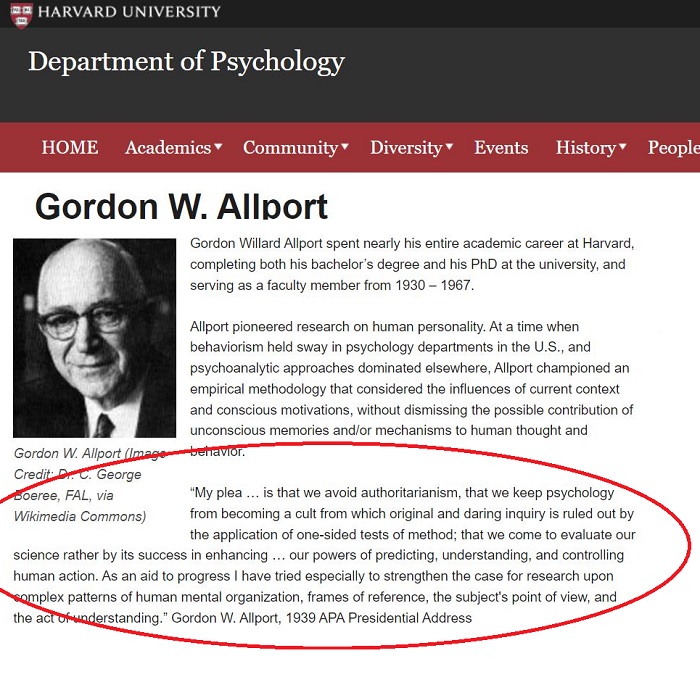

Humanistic psychology, began originally as a legitimate form of academic discourse, did not appear on the scene de novo. One major line of influence had grown out of the older personality and social psychologies developed by previous figures such as Gordon Allport, Henry A.Murray, and Lois Murphy during the 1930s and 1940s. These older psychologists had been the first generation after William James to successfully resist the takeover of academic psychology by reductionistic empiricism, which in James’s time meant the structuralism of Titchener and Münsterberg and the atomism of Cattell and Witmer. After James, the opposition became the conditioning theories of Pavlov and Watson and the tyranny of testing. After 1930, control over the definition of scientific psychology meant the laboratory experimentalism of Boring, Stevens, Lashley, Hull, and Spence. After the era of the personality-social psychologists, humanistic psychologists continued to carry on this debate and to field an alternative psychology, which raged at the national level in the academy into the early 1960s.- Eugene Taylor, The Mystery of Personality, A History of Psychodynamic Theories

Harvard University 1924 – the beginning of ‘Transactional’ psychology. A movement beyond mechanical, laboratory, statistical, and mathematical-based analysis of personality. This kind of psychology was what the Psilocybin Project was following.

The Social Relations Department – Humanists vs Experimentalist

“You’re just what we need to shake things up at Harvard” – David McClelland to Timothy Leary, 1959

The Department of Psychology at Harvard continued to be divided between its experimentalists, who dominated the department, and its social-clinical wing, which in the 1960s resided in Social Relations.

The problem, University President Dean Pusey thought, was “[h]ow to build back a strong unified department of psychology?” That would not be easy. Social psychologist David McCelland, who became the chair of Social Relations in 1962, complained of how hard it was to deal with Stanley Smith Stevens, the director of the Psychological Laboratory. Stevens was a severe, traditional experimentalist, uninterested in undergraduates. But the standing of Harvard’s experimental psychologists was not to be sneezed at. Stevens’s colleague Georg von Bekesy won a Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1961 for his work on the inner ear. And the Psychological Lab was the home of the brilliant (and controversial) B. F. Skinner’s work on conditioning. The problem required breaking through into new territory.

The Projects Design

The project in concert with David McLelland was designed to study the effects of psilocybin on Harvard graduate students and others who qualified and were interested. Over almost three years of its operation, it was said to have administered (documented) close to 400 trials to willing and informed participants. During the years of its experiments and outside of its controls many other “experiments” were going on, all over the country. What was happening in Cambridge was only the top of the ivory towers where intelligencia – and therefore knowledge holders – studied.

Participants:

The Core five of the program were; Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, Ralph Metzner, Gunther Weil, George Litwin (Swami Premdana).

Other participants: Ralph Schwitzgebel, Pearl Chan. Michael Kahn. Michael Hollingshead, , Walter Pahnke, Al Alschuler, Paul Lee, Rolf von Eckantoberg, Walter Pahnke, Huston Smith, Ralph Metzner, James Ciarlo, Jonathan Shay, and Frank Ferguson.

Harvard Professors and Lecturers:

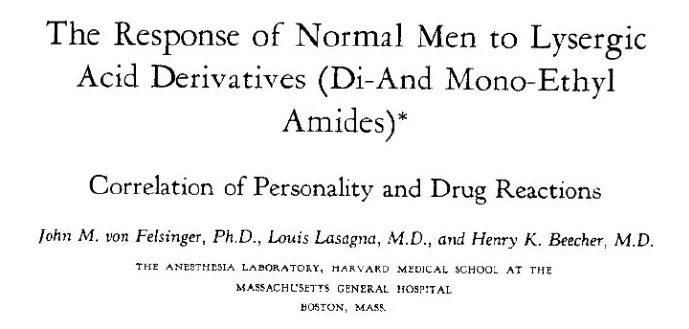

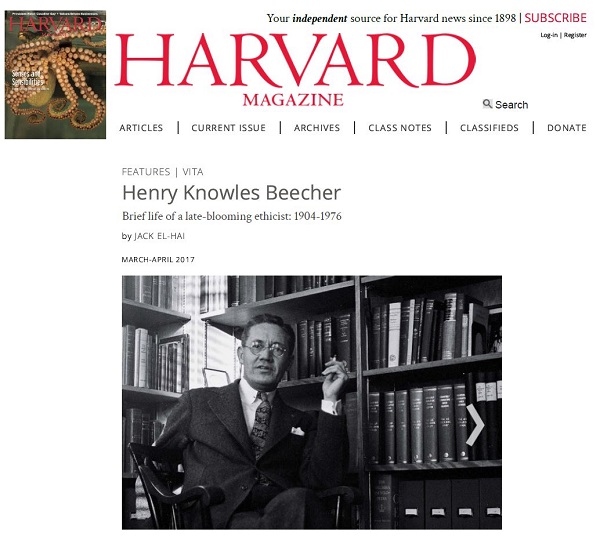

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, but many other Harvard luminaries such as Richard Schultes, Andrew Weil, David MCelland, Herbert Kelman, Elliott Perkins, Nathan Pusey, Dana Farnsworth, Dean John Monro, Herbert Kelman, Henry Beecher, and Harry Murray.

A Brief Look Back at the Times

Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) and Timothy Leary, 1961

Richard Alpert became acquainted with psychedelics, as he expresses it, with a lot of help from friends.”This actually began in 1957, after acquiring his Ph.D., when he began working part-time as a therapist at the Stanford Health Service. Some of his clients were initially from the “Perry Lane” crowd at Stanford, a group with allegiance to Beatnik activities at the time. It was his first patient- Vic Lovell, “a beautiful writer,” Alpert comments, to whom Ken Kesey dedicated One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—who initially gave him marijuana.

Alpert recalls taking some mescaline at one of the Perry Lane parties. But the experience wasn’t dramatic, and he doesn’t remember it very well. Yet marijuana began to mellow him out, he noticed over time, even though its effects weren’t profound. Those giving it to him, he feels now, were largely taking pity on him, since they saw him as being quite square, tight and neurotic. Still, he was a young instructor—”politically charming”—and was thought a nice guy. The marijuana he smoked seemed to have an accumulating effect—a “softening of my edges.”

In the summer of 1*560, Alperl went to Mexico to meet Timothy Leary in Cuernavaca. Leary was joining him as part of the faculty at Harvard, and they planned to fly an airplane Alpert owned across South America. Leary had had his initial psilocybin trip just before Alpert landed, and he was overwhelmed. At the airport in Mexico City, Leary greeted Alpert by saying that he had just had an experience lasting six hours that had taught him more than his years studying psychology had ever taught him. “That was impressive to a fellow psychologist,” Alpert says. As it happened, Leary and the others with him had eaten all the mushrooms and no more were left for Alpert. Alpert went on leave-of-absence from Harvard that fall in order to teach at Berkeley. He returned to Cambridge for the winter term of 1961.

On March 6th, in Leary’s home in Newton, Mass., during a huge snowstorm, Alpert took synthetic psilocybin that had been acquired from Sandoz Pharmaeuticals. This became an important turning point in his life, as he quickly became conscious that he “wasn’t who he was.” Here’s a partial description of that event:

Sitting in the living room of Leary’s house in suburban Boston, Alpert saw a figure in academic robes standing a few feet away and recognized himself in his role as Harvard professor. The figure kept changing to other aspects of his identity—musician, pilot, lover, bon vivant—that had somehow dissociated themselves from his body. And then to his horror he watched his body itself disappear as he looked down on it—first his forelegs, then all his limbs, then his torso— and he knew for the first time that there was “a place where ‘I’ existed independent of social and physical identity . .. beyond Life and Death.” At about five in the morning he walked the few blocks to his parents house in a driving snowstorm and began shoveling the driveway, laughing aloud with joy …

Reflecting later about this trip, Alpert comments that that was the dramatic moment when he shifted his perspective from a reality that had sec med solid since he had been a child. He now feels that he used psychology until then mainly to rationalize, strengthen and solidify his early conceptions.

At this point, Alpert held several Harvard appointments — a psychotherapist with the University Health Services, in e Social Relations Department, the School of Education, and the Psychology Department. His specialties were child development, human motivation, Freudian theory, and achievement motivation. He was Associate Director of the Laboratory of ran Development, an assistant to David McClelland at the center for research in Personality, and teaching a course thatLeary called “Existential Transactional Behavior Change.” Now he also became fascinated with — and a faculty sponsor for the Psilocybin Research Project that had been set up at Harvard by Leary, Aldous Huxley, Ralph Metzner, Gunther Well, George Litwin, Frank Barron and others.

In the beginning, things looked bright

During the past year, we at Harvard, under the instigation and direction of Dr’s Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert have been exploring in some depth the uses of consciousness-altering substances. In our work, we have used several different substances (LSD, mescaline, psilocybin) and continue to be interested in the potential of all of these. In the course of these investigations, owever, we have concentrated on the use of psilocybin. We have come to believe that psilocybin has the potential to facilitate for an individual the experience of major insights and problem solutions of an intellectual-emotional nature. the real of these insights or problem solutions is in any area which is meaningful to that individual be it social or personal, intellectual, religious, or philosophical.

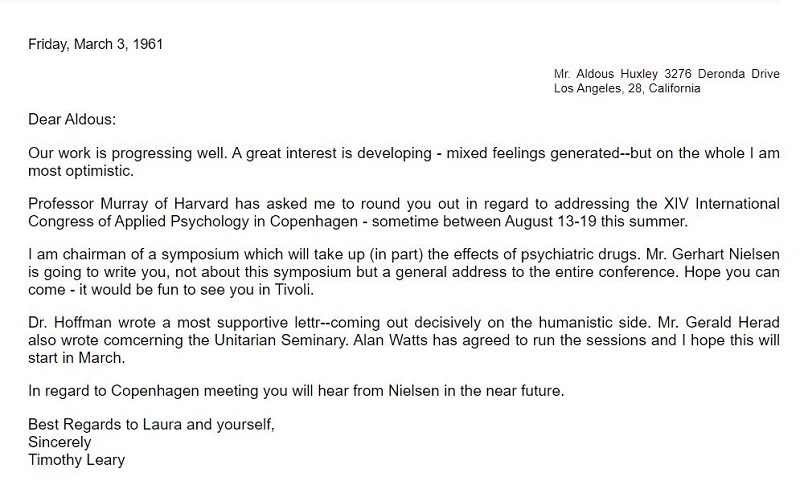

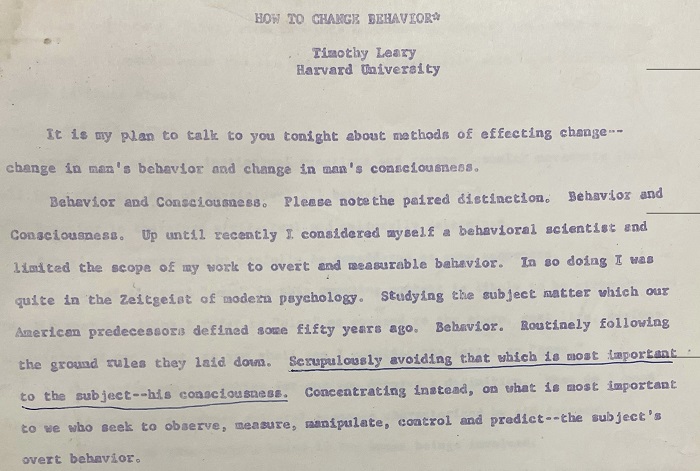

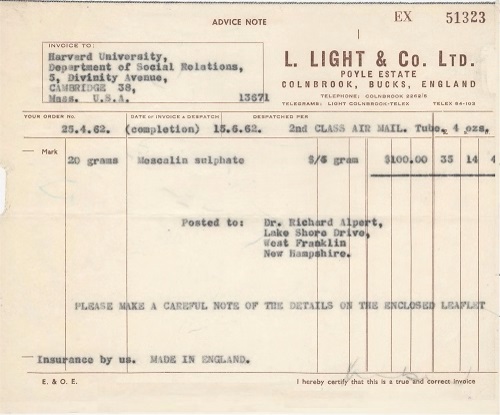

14th Annual Congress of Applied Psychology

Copenhagen, 1961

It is my plan to talk to you tonight about methods of effecting change—change in man’s behavior and change in man’s consciousness. Behavior and consciousness. Please note the paired distinction. Behavior and consciousness. Up until recently I considered myself a behavioral scientist and limited the scope of my work to overt and measurable behavior. In so doing I was quite in the Zeitgeist of modern psychology, studying the subject matter which our American predecessors defined some fifty years ago, behavior, routinely following the ground rules they laid down, scrupulously avoiding that which is most important to the subject—his consciousness, concentrating instead, on what is most important to we who seek to observe, measure, manipulate, control and predict—the subject’s overt behavior. This decision to turn our backs on consciousness is, of course, typically western and very much in tune with the experimental, objective bent of Western science. read more >>>

Mescaline and LSD were also available (but not used in the projects studies)

Michael Hollingshead introduces Timothy Leary to LSD in December 1961

After turning Leary on, Hollingshead became an active participant in many of the ur-moments of psychedelic culture, such as the Concord Prison Project of 1961–’63 (where Leary used psilocybin and psychotherapy to reduce recidivism), the Good Friday Experiment of 1962 (where volunteers from Harvard’s Divinity School explored the spiritual properties of psilocybin), and the Millbrook commune Leary established in Upstate New York in 1963.

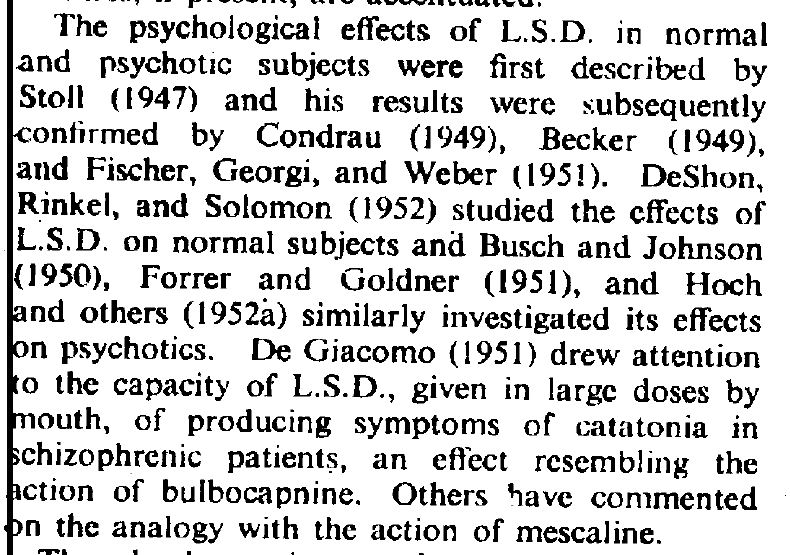

*Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was made available by Sandoz Laboratory in Switzerland to research institutions, psychiatrists and physicians in 1947 under the trademark name, Delysid, for its potential in medicinal-psychiatric use. Playing the role of a drug aid in the context of psychoanalytic and psychotherapeutic treatment, LSD gained popularity in clinical treatment settings, notably by Ronald Sandison in European practice and Humphry Osmond in North America.

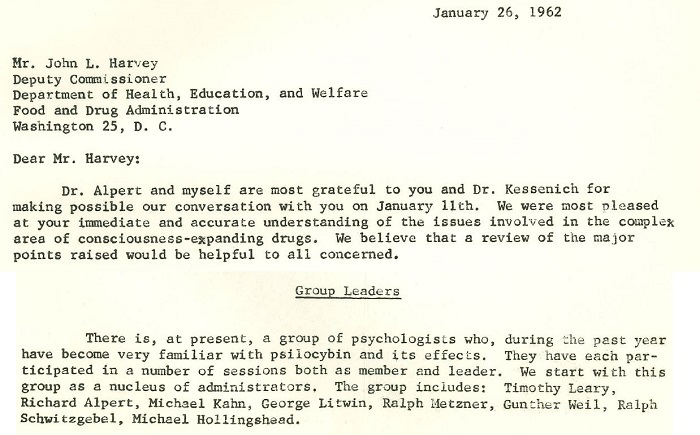

Working with Washington

BACKGROUND

“It is not I who speak,” said Heraclitus, “it is the logos.”

“If you ask a shaman where his or her imagery came from, they are likely to reply: I didn’t say it, the mushrooms did”

How psilocybin mushrooms became popular in the US.

“IT KIND OF POLISHES ALL YOUR FLAWS AWAY”: LONG-TERM EXPERIENCES WITH PSILOCYBIN MUSHROOMS AND THE INFLUENCE OF SET AND SETTING By Danielle Daniel

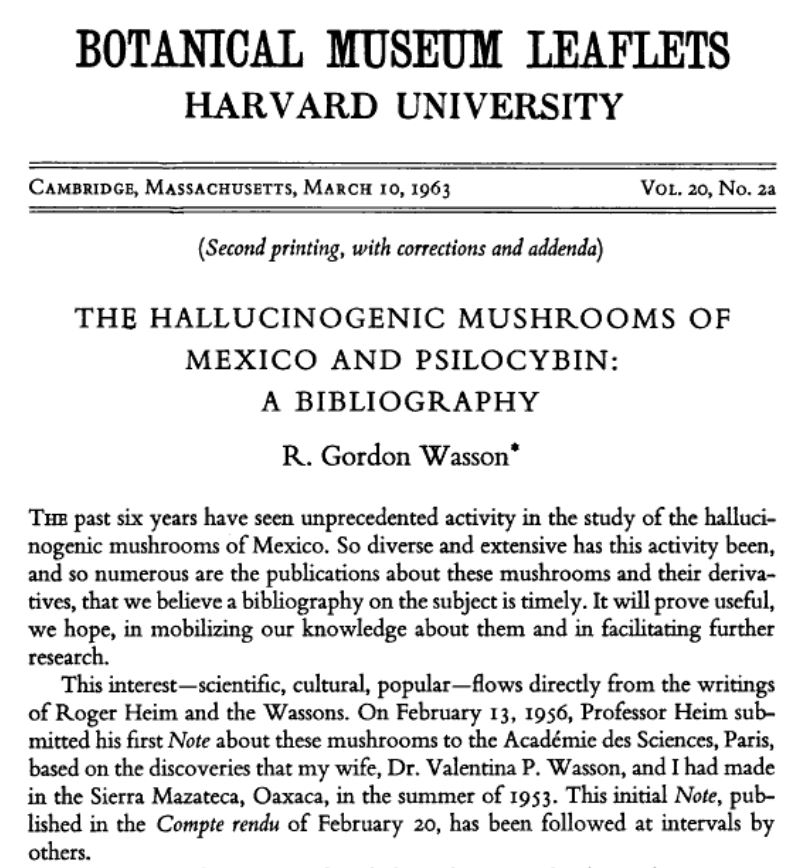

A chain of events led to the rediscovery of the secret Mazatec Indian mushroom ceremonies. In 1937 Blas Pablo Reko, an Austrian Physician, collected mushroom samples for Richard Schultes, a Harvard ethnobotanist (Shultes 1939). During Reko’s research in Mexico, he reported evidence of ceremonial mushroom use in Oaxaca (Shultes 1939; Guzman 2008). In 1938, Reko traveled to Oaxaca with Schultes to gather mushroom samples, which were delivered to Harvard University for analysis. Intrigued by the evidence of Mazatec mushroom ceremonies, North American anthropologist Jean Bassett Johnson traveled to Oaxaca to observe a mushroom ceremony the following year.

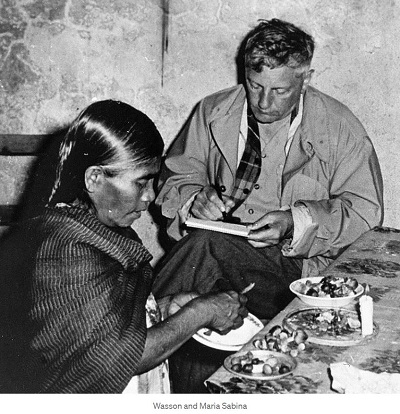

Johnson became the first documented Western scientist to witness the traditional ceremony. In the 1940’s mycologist Rolf Singer studied Shultes’ samples and identified some of the mushrooms as psilocybe cubensis, which in turn were documented as narcotic mushrooms. Inspired by the work of Schultes, Robert Gordon Wasson, a wealthy U.S. banker, and his wife Valentina Pavlovna traveled to Mexico in 1952 intending to gain a deeper understanding of how psilocybin mushrooms were used in the Mazatec culture.

Psilocybin containing mushrooms became widely recognized in the United States in the late 1950s from Wasson’s research in Mexico (Letcher 2007). Wasson traveled to Mexico 10 times to learn about psilocybin mushrooms and to experience a psilocybin mushroom ceremony. Healing ceremonies in Mexico involve a curandero (shaman) consuming psilocybin mushrooms to understand a patient’s illness and what that patient should do to get well; it was believed that the mushroom gave instructions to the curandero to relay to the patient.

In 1955 Wasson met Maria Sabina, a well-known and respected curandero, in Oaxaca. Surprisingly, Sabina allowed Wasson to eat psilocybin mushrooms with her in a ceremony. Wasson was the first documented Westerner to ingest mushrooms in a ceremonial setting. For Maria Sabina, and the Mazatec Indian culture, psilocybin mushrooms were recognized as spirits with whom the curanderos built relationships, and through that relationship, the mushroom would provide guidance and healing. Wasson sat in ceremony with Sabina several times and made recordings of her ceremonial songs to introduce to the western world. In 1957 Wasson published an article in Life magazine describing his psilocybin mushroom experience, introducing the term “magic mushrooms” in the article title (Letcher 2007). This same year the term psychedelic was also introduced to describe mind-altering substances (Pahnke 1969).

Long History

Psilocybin Projects First Studies

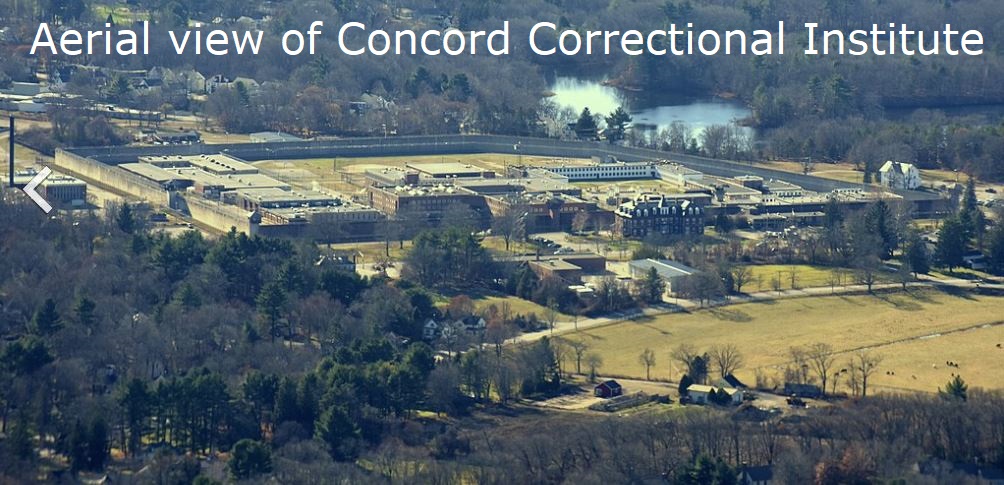

Dr. Timothy Leary received permission from the State Commission of Correction to give psilocybin to thirty-five inmates at Concord State Reformatory.

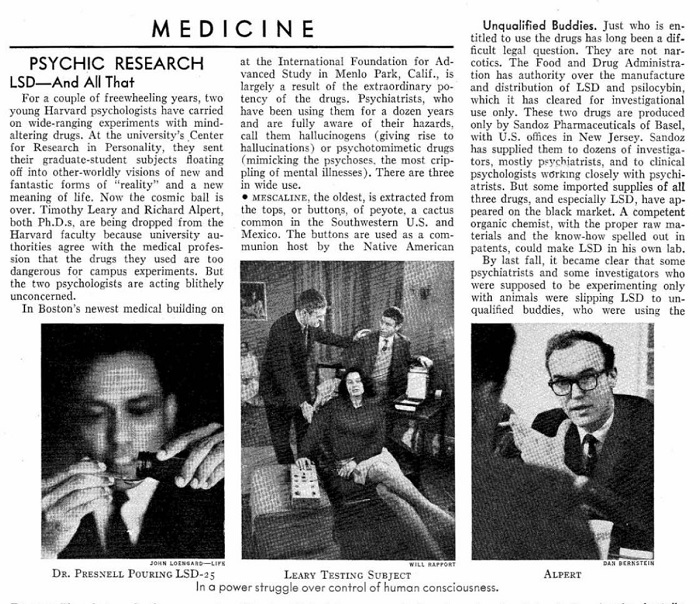

The Concord Prison Experiment was conducted from 1961-1963 inside the walls of the Concord State Prison, a maximum-security prison for young offenders, in Concord, MA by a team of researchers at Harvard University under the direction of Timothy Leary, which included Michael Hollingshead, Dr. Allan Cohen, Dr. Alfred Alschuder, Dr. George Litwin, Dr. Ralph Metzner, Dr. Gunther Weil, and Dr. Ralph Schwitzgebel, with Dr. Madison Presnell as the medical and psychiatric adviser.

The original study involved the administration of psilocybin to assist group psychotherapy to 32 prisoners in an effort to reduce recidivism rates. The experiment was designed to evaluate whether the experiences produced by psilocybin could inspire prisoners to leave their antisocial lifestyles behind once they were released. How well it worked was to be judged by comparing the recidivism rate of subjects who received psilocybin with the average for other Concord inmates. Read more >>>

In February a Crimson article by Andrew Weil a newsletter was sent out.

‘Better Than a Damn’

From the Bottle

Recently our Western science has provided, in the form of chemicals, the most direct techniques for opening new realms of awareness. William James used nitrous oxide and ether to “stimulate the mystical consciousness in an extraordinary degree.” Today the attention of psychologists, philosophers, and theologians is centering on the effects of three synthetic substances—mescaline, lysergic acid, and psilocybin. What are these substances? Medicines or drugs or sacramental foods? It is easier to say what they are not. They are not narcotics, nor intoxicants, nor energizers, nor anaesthetics, nor tranquilizers. They are, rather, biochemical keys which unlock experiences shatteringly new to most Westerners. For the last two years, staff members of the Center for Research in Personality at Harvard University have engaged in systematic experiments with these substances. Our first inquiry into the biochemical expansion of consciousness has been a study of the reactions of Americans in a supportive, comfortable naturalistic setting. We have had the opportunity of participating in over one thousand individual administrations. From our observations, from interviews and reports, from analysis of questionnaire data, and from pre-and post experimental differences in personality test results, certain conclusions have emerged.

(1) These substances do alter consciousness. There is no dispute on this score.

(2) It is meaningless to talk more specifically about the “effect of the drug.” Set and setting, expectation, and atmosphere account for all specificity of reaction. There is no “drug reaction” but always setting-plus-drug.

(3) In talking about potentialities it is useful to consider not just the setting-plus-drug but rather the potentialities of the human cortex to create images and experiences far beyond the narrow limitations of words and concepts. Those of us on this research project spend a good share of our working hours listening to people talk about the effect and use of consciousness-altering drugs. If we substitute the words human cortex for drug we can then agree with any statement made about the potentialities—for good or evil, for helping or hurting, for loving or fearing. Potentialities of the cortex, not of the drug. The drug is just an instrument.

To continue reading click HERE

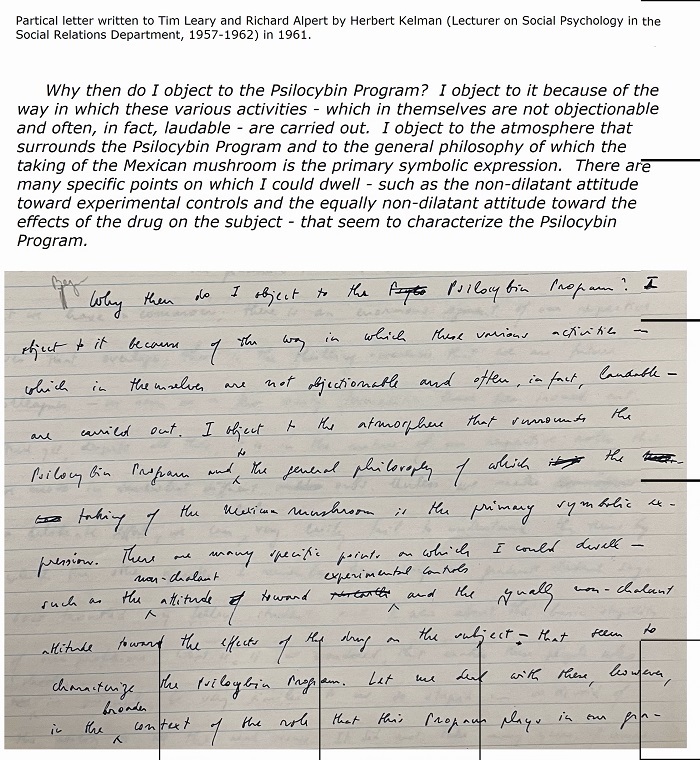

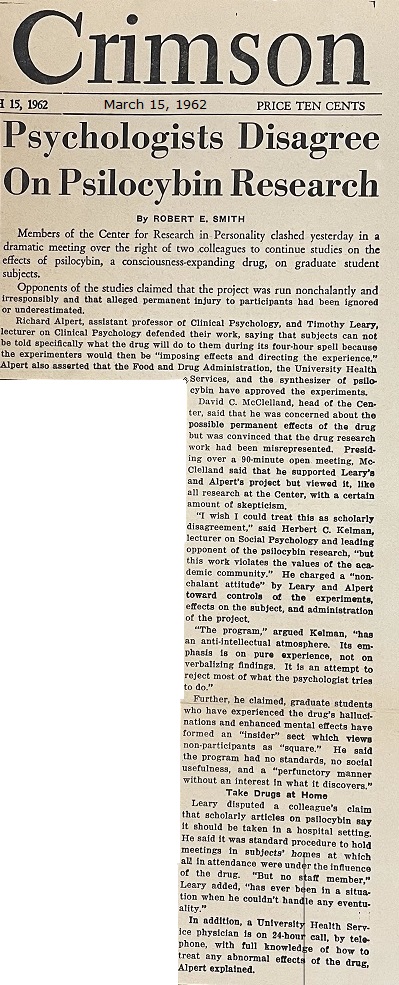

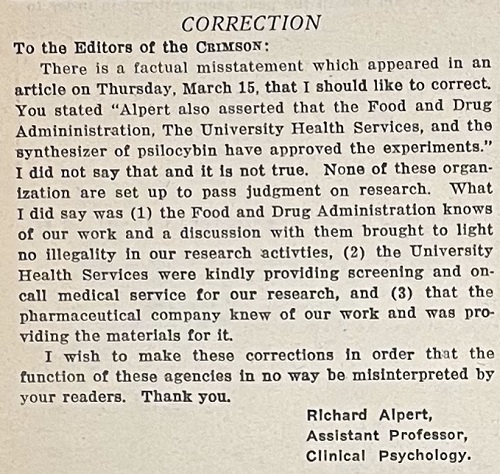

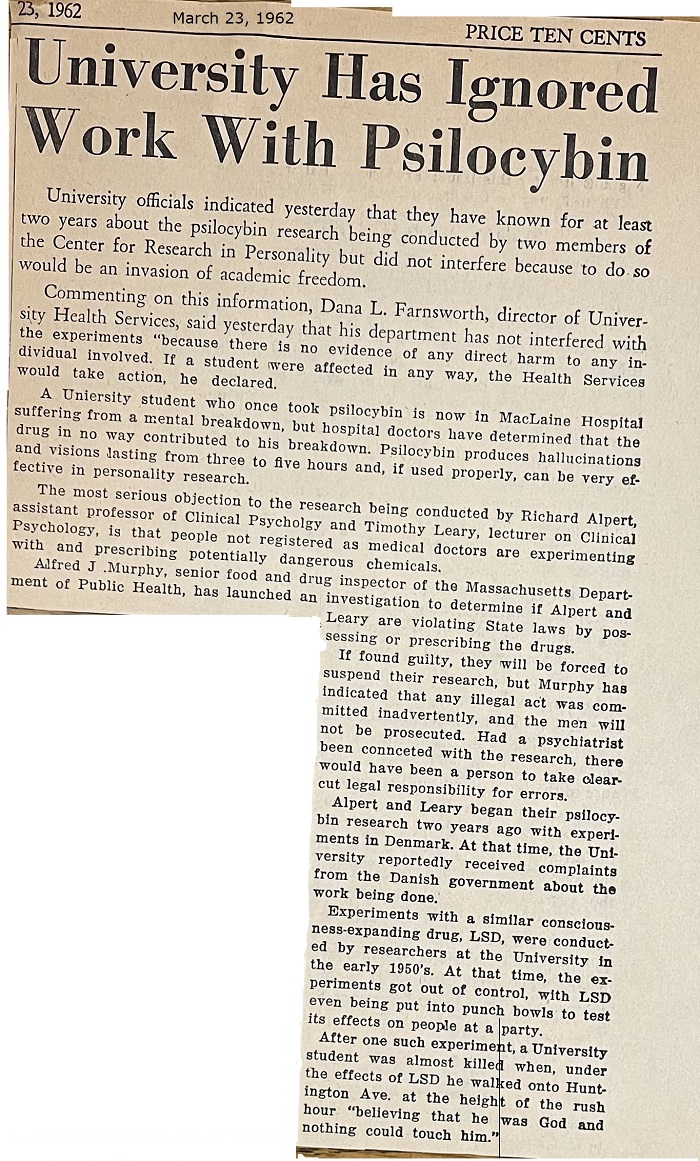

The Controversy Begins – March 1962

‘Why then do I object to the Psilocybin Program? I object to it because of the way in which these various activities – which in themselves are not objectionable and often, in fact, laudable – are carried out. I object to the atmosphere that surrounds the Psilocybin Program and to the general philosophy of which the taking of the Mexican mushroom is the primary symbolic expression. There are many specific points on which I could dwell – such as the non-dilatant (non-Newtonian) attitude toward experimental controls and the equally non-dilatant attitude toward the effects of the drug on the subject – that seem to characterize the Psilocybin Program.” – Herb Kelman* (Lecurer on Social Psychology in the Social Relation Department) letter to Tim Leary and Richard Alpert.

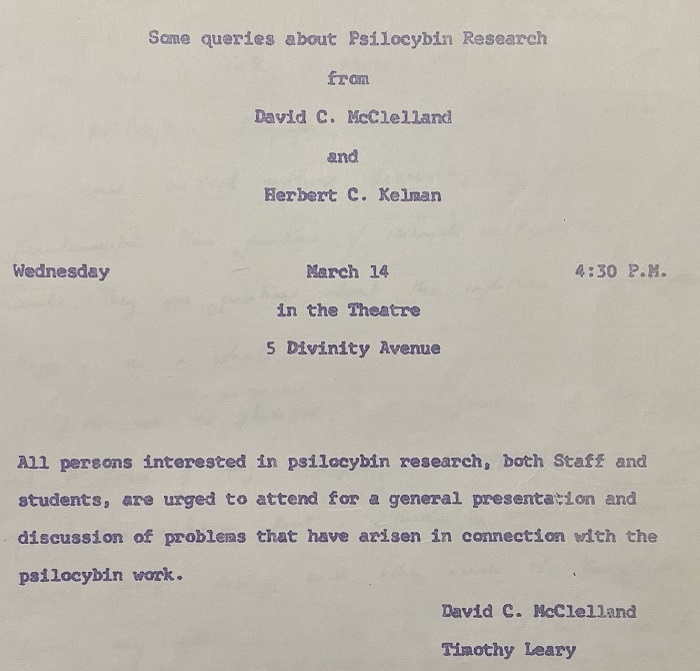

(In) March 1962 progress meeting marked the beginning of the end of Leary’s Harvard career, no one had intended to drive Leary and his research off campus. In fact, McClelland came to Leary with the idea of a progress meeting and allowed Leary to co-sponsor it. Kelman, who suggested the meeting to McClelland, wanted only to communicate his concerns to the students and had envisioned a small, civilized meeting of faculty and graduate students.[1] Instead, on March 14, an overwhelmingly large group crowded into the meeting room, including a reporter from The Harvard Crimson. The Boston press picked up the story and the progress meeting became, after the fact, a media event.*

[1] Kelman, interview; and, David C. McClelland and Timothy Leary, Announcement of March 14, 1962 Meeting, “Some Queries About Psilocybin Research,” March 1962,1. Courtesy of Herbert Kelman.

*Robin M. Wasserman – Robin wrote her senior thesis about Dr. Timothy Leary, who co-conducted studies known as the Psilocybin Project

* Interesting Note: Herb Kelman, Harvard’s Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of social ethics, admitted in a Globe Washinton Bureau report that he received a $1,000 grant for a non-related drug study three years before he successfully argued for the expulsion of Leary and Alpert. The grant was from a CIA MK-ULTRA program called Human Ecology Fund run by Sidney Gottlieb. Sidney Gottlieb was considered the darkest, sadistic, most violent, and most horrific figure in the U.S. government’s efforts to fight communism in the 1950s. – Al Larkin, global Washington Bureau.

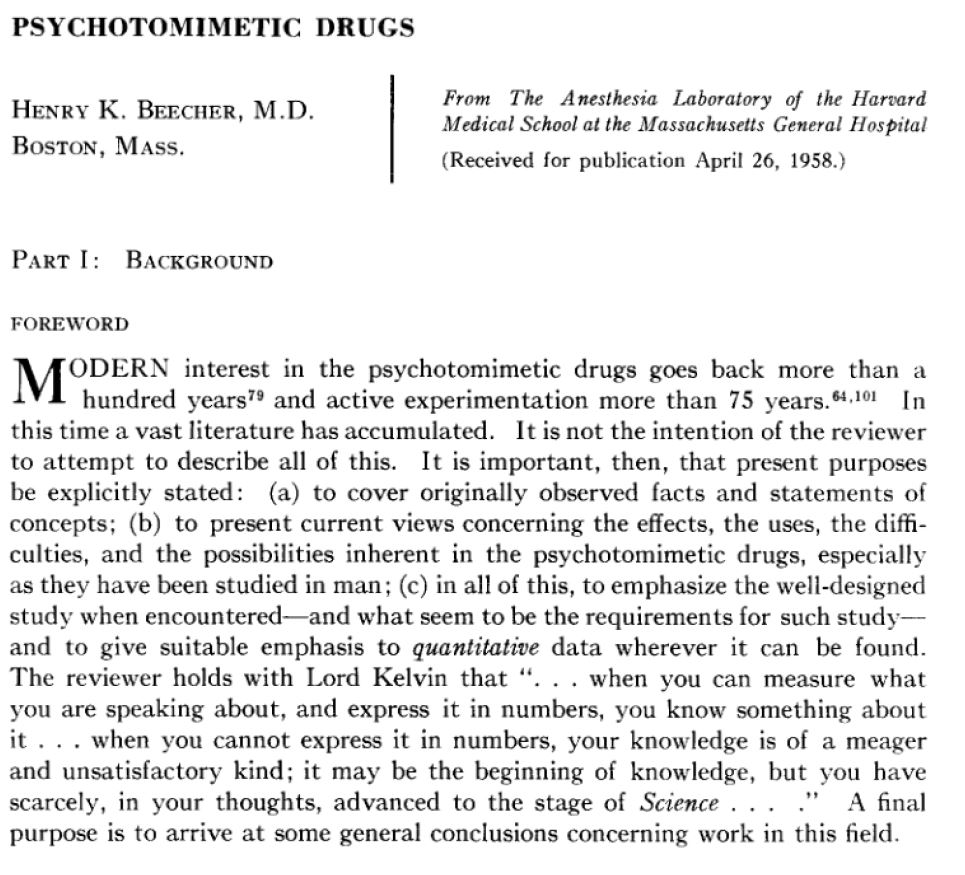

Not Scientific!

March 15, 1962

Beecher quotes Lord Kelvin here which capsulized the “problem”.

Psychologists Disagree On Psilocybin Research

By ROBERT E. SMITH

March 15, 1962

Members of the Center for Research in Personality clashed yesterday in a dramatic meeting over the right of two colleagues to continue studies on the effects of psilocybin, a consciousness-expanding drug, on graduate student subjects.

Opponents of the studies claimed that the project was run nonchalantly and irresponsibly and that alleged permanent injury to participants had been ignored or underestimated.

Richard Alpert, assistant professor of Clinical Psychology, and Timothy Leary, lecturer on Clinical Psychology defended their work, saying that subjects can not be told specifically what the drug will do to them during its four-hour spell because the experimenters would then be “imposing effects and directing the experience.” Alpert also asserted that the Food and Drug Administration, the University Health Services, and the synthesizer of psilocybin have approved the experiments.

David C. McClelland, head of the Center, said that he was concerned about the possible permanent effects of the drug but was convinced that the drug research work had been misrepresented. Presiding over a 90-minute open, meeting, McClelland said that he supported Leary’s and Alpert’s project but viewed it, like all research at the Center, with a certain amount of skepticism.

“I wish I could treat this as scholarly disagreement,” said Herbert C. Kelman, lecturer on Social Psychology and leading opponent of the psilocybin research, “but this work violates the values of the academic community.” He charged a “nonchalant attitude” by Leary and Alpert toward controls of the experiments, effects on the subject, and administration of the project.

“The program,” argued Kelman, “has an anti-intellectual atmosphere. Its emphasis is on pure experience, not on verbalizing findings. It is an attempt to reject most of what the psychologist tries to do.”

Further, he claimed, graduate students who have experienced the drug’s hallucinations and enhanced mental effects have formed an “insider” sect which views non-participants as “square.” He said the program had no standards, no social usefulness, and a “perfunctory manner without an interest In what it discovers.”

Take Drugs at Home

Leary disputed a colleague’s claim that scholarly articles on psilocybin say it should be taken in a hospital setting. He said it was standard procedure to hold meetings in subjects’ homes at which all in attendance were under the influence of the drug. “But no staff member,” Leary added, “has ever been in a situation when he couldn’t handle any eventuality.”

In addition, a University Health Service physician is on 24-hour call, by telephone, with full knowledge of how to treat abnormal effects of the drug, Alpert explained.

March 16, 1962

March 17, 1962

The Harvard Crimson

Leary write to Pusey

March 19

There are some critical administrative and political questions that have arisen in conjunction with our work. We pose these as problems even though we presently are in the process of formulating appropriate plans which will solve many of these problems.

It is apparent from the discussion above of the potential of psilocybin that even the recognition of such potential cane about in part through the maximally flexible exploratory efforts to data. We are all only too aware of how stifling to creative endeavor the too-early imposition of controls can be.

We are, however, equally aware that there is considerable anxiety in the society about the use of such substances. This anxiety is reflected in the attempts to impose more and more limiting controls. Some of these are indeed justified by the absence of long-term data but others are the product of anxiety (and, at times, vested interest ). It is difficult but necessary to separate the motives for control. We must evaluate where on the continuum of control such research should be carried out.

This much seems clear to us, the safety and success of a psilocybin experience depends upon the maturity and security of the administrator. A tolerant, supportive, democratic, non-anxious experienced administrator will almost always bring about a positive experience. The control and responsibility for administration of psilocybin should be in the hands of people so qualified. Any system of responsibility which is not based on these criteria will probably result in negative experiences.

The mistrust, misunderstanding and resentment that our work has elicited is partly our faulto The time pressures involved in our exploratory studies have led to inadequate communication with the larger community about our work and our aims. But we have also sent a definite unwillingness in many people to consider new ideas and values fairly.

We are presently deliberating with many advisors as to the means of creating a supportive community setting for this type of research. If our research programs are to achieve any order of success, they will need the close and open cooperation of our subjects and a climate or community in which our subjects can speak openly about their participation. Further, we must feel to explore new methods and ideas without fear of harassment and rumor.

Historically, the University has often provided the necessary asylum to researchers involved in work which departs radically from current cultural positions. Harvard is well known for its firm position of support for academic freedom. Therefor we anticipate that if such a supportive community for our work can be developed, the climate of Harvard will be most conducive to our continued efforts.

What criteria should be utilized in assessing (1) who can carry out research with psilocybin (2) under what conditions and (3) for what purposes? We must tamper any power we might have to control the nature of research and staff with infinite wisdom. We are presently endeavoring to form an advisory panel of men who have experience in the many fields in which psilocybin might prove be useful.

This panel, which would of course include experienced researchers, would evaluate and oversee the increasingly numerous requests by researchers to collaborate in the work. It la our hope that such a panel would reflect sufficient breadth of interest and opinion and sufficient statue in the community to assure the maintenance of optimal freedom for creative use of psilocybin.

At present our staff which is composed of a wide variety of researchers and scholars are contributing their time and effort to this work without financial compensation. What monies we have needed for the maintenance of an administrative office and for miscellaneous matters have been privately contributed. The psilocybin has been provided without cost by the Sandoz Laboratories.

It is unlikely that the program of research of which we conceive could be carried out with aa informal and uncertain financial structure as now exists. We are, therefore, seriously considering the possibility of creating a non-profit research foundation (probably here at Harvard) which could further stabilize our endeavors and allow for more long-term planning.

Our Staff

We have been researching with psilocybin for less than a year. In the course of that brief period the research potentials that have come to light have so enthused many of the members of the community that the research team has expanded considerably — adding to its ranks deeply committed collaborators. It is giving all of us a great deal of pleasure to be part of a team dedicated to such a significant endeavor.

This paper is a product of the joint efforts of Richard Alpert, Michael Kahn, Timothy Leary, George Litwin, Ralph Metzner and Gunther Weil, and these investigators are primarily responsible for the research described here.

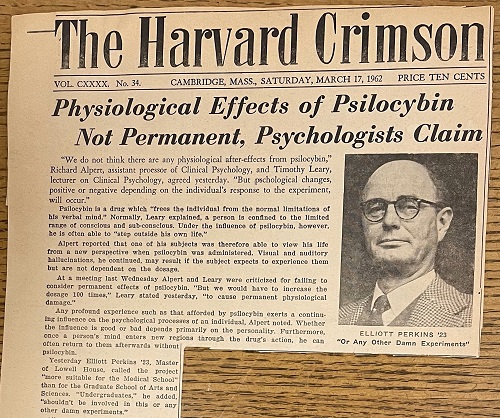

SATURDAY, MARCH 17, 1962

Physiological Effects of Psilocybin Not Permanent, Psychologists Claim

“We do not think there are any physiological after-effects from psilocybin,” Richard Alpert, assistant professor of Clinical Psychology, and Timothy Leary, lecturer on Clinical Psychology, agreed yesterday. “But psychological changes, positive or negative depending on the individual’s response to the experiment, will occur.”

Psilocybin is a drug which “frees the individual from the normal limitations of his verbal mind.” Normally, Leary explained, a person is confined to the limited range of conscious and sub-conscious. Under the influence of psilocybin, however, he is often able to “step outside his own life.”

Alpert reported that one of his subjects was therefore able to view his life from a new perspective when psilocybin was administered. Visual and auditory hallucinations, he continued, may result if the subject expects to experience them but are not dependent on the dosage.

At a meeting last Wednesday Alpert and Leary were criticized for failing to consider permanent effects of psilocybin. “But we would have to increase the dosage 100 times,” Leary stated yesterday, “to cause permanent physiological damage.”

Any profound experience such as that afforded by psilocybin exerts a continuing influence on the psychological processes of an individual, Alpert noted. Whether the influence is good or bad depends primarily on the personality. Furthermore, once a person’s mind enters new regions through the drug’s action, he can often return to them afterwards without psilocybin.

Yesterday Elliott Perkins ’53, Master of Lowell House, called the project “more suitable for the Medical School” than for the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “Undergraduates,” he added, “shouldn’t be involved in this or any other damn experiments.”

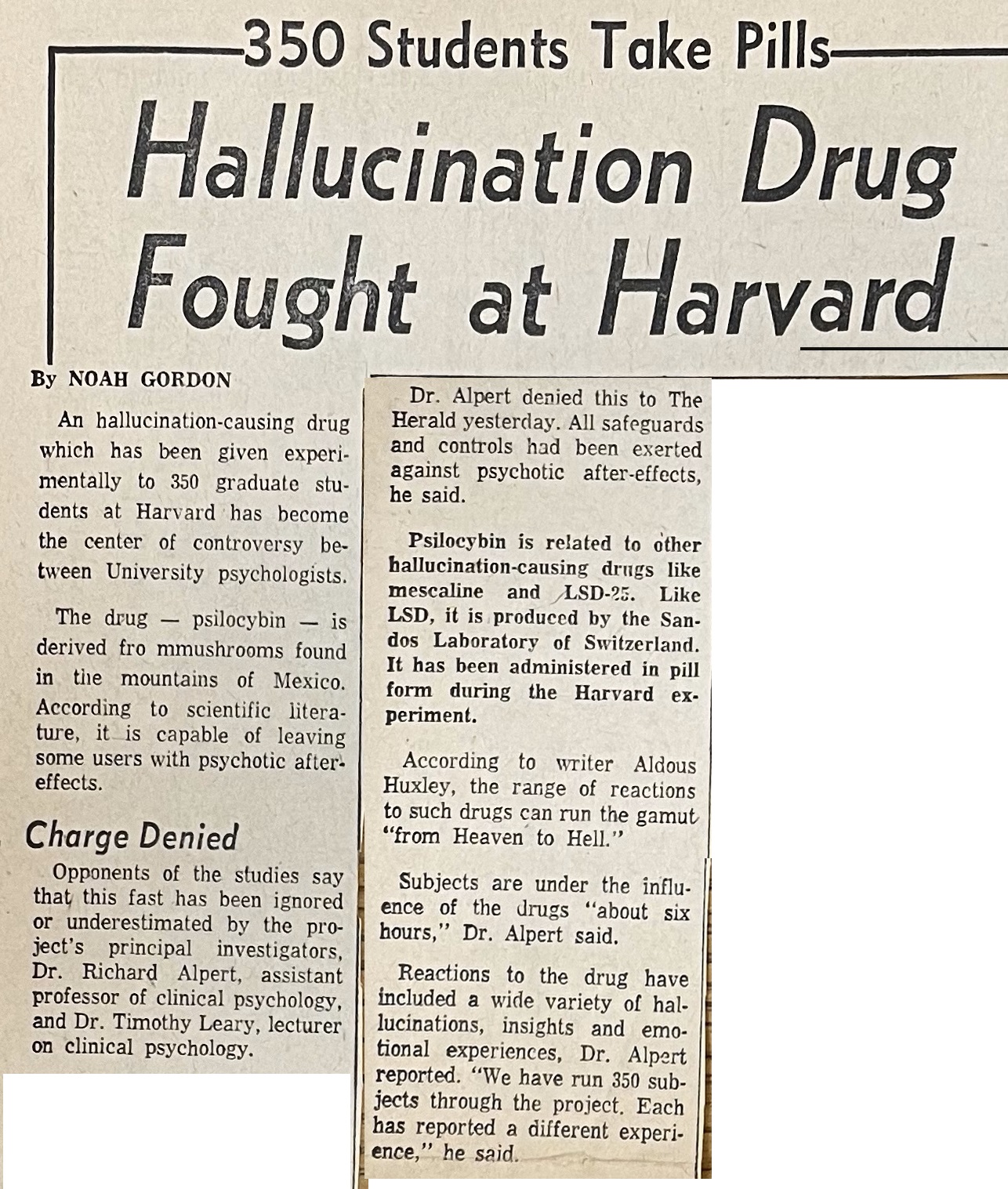

The Story goes public – The Beginning of the End

Next day – March 16

Boston Globe

These activities attracted the attention of the FDA and Massachusetts law-enforcement officials, who made inquiries. Harvard and the Harvard Crimson responded by warning students against taking LSD. The warnings were picked up by the mass media–– and were among the first nationally circulated publicity for LSD. As the FDA and state officials continued their investigation, a scandal broke.

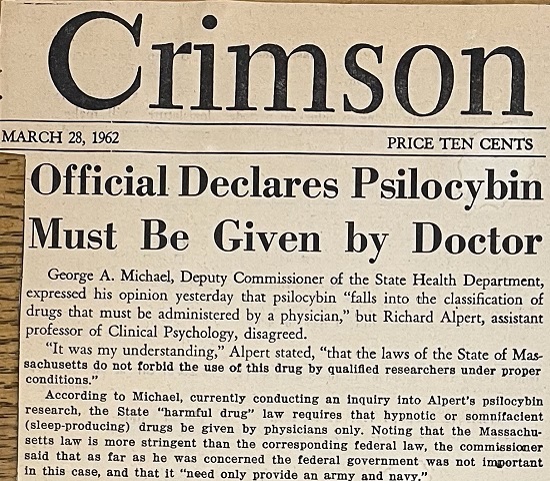

Shortly after the March 15th meeting, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health initiated an investigation into Leary’s program. The Department had yet to determine whether psilocybin should be classified as a “harmful” drug – if it were, only medical doctors would be authorized to legally administer it and Leary would be liable to prosecution. Eventually, Leary, Alpert, the state, and the University reached a compromise. The researchers agreed that they would turn over all their supplies to University Health Services (UHS), that they would only administer the drug with a physician present, and that they would never use undergraduates in their research. Leary escaped prosecution but chafed at having yet another set of restrictions imposed on his work.

Tuning in : Timothy Leary, Harvard, and the boundaries of experimental psychology – a thesis presented by Robin M. Wasserman, 2000.

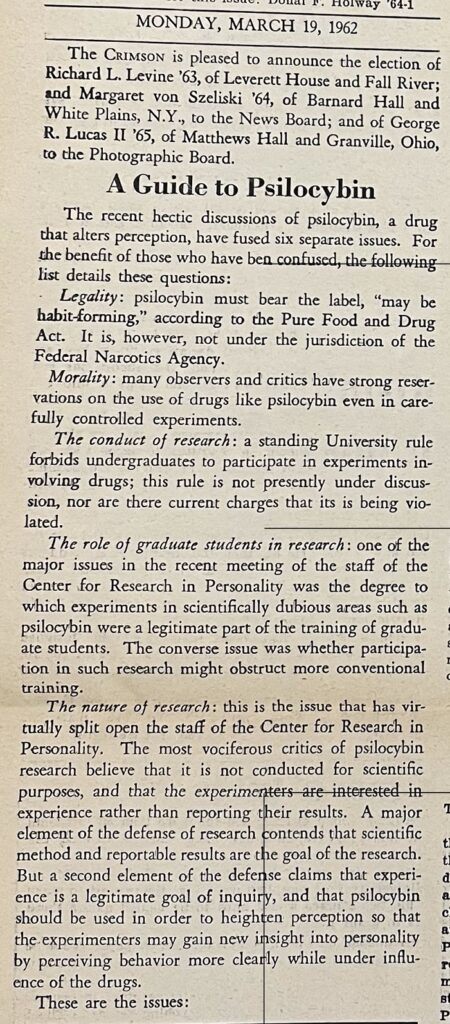

March 19 – Crimson Guide (and clarification)

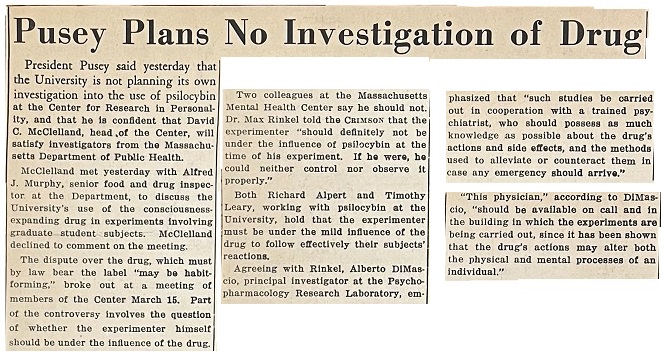

After there were calls for the state to get involved President Nathan Pusey was quoted in the Crimson

Pusey Plans No Investigation of Drug

President Pusey said yesterday that the University is not planning its own investigation into the use of psilocybin at the Center for Research in Personality, and that he is confident that David C. McClelland, head of the Center, will satisfy investigators from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

McClelland met yesterday with Alfred J. Murphy, senior food and drug inspector at the Department, to discuss the University’s use of the consciousness- expanding drug in experiments involving graduate student subjects. McClelland declined to comment on the meeting.

The dispute over the drug, which must by law bear the label “may be habit-forming.” broke out at a meeting of members of the Center March 15. Part of the controversy involves the Question of whether tho experimenter himself should be under the Influence of the drug.

Two colleagues at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center say he should not. Dr. Max Rinkel told the Crimson that the experimenter “should definitely not be under the influence of psilocybin at the time of his experiment. If he were, he, could neither control nor observe II < properly.”

Both Richard Alport and Timothy Leary, working with psilocybin at the University, hold that the experimenter must be under the mild influence of the drug to follow effectively their subjects’ reactions.

Agreeing with Rinkel, Alborto DIMasclo, principal Investigator at the Psychopharmacology Research Laboratory, emphasized that “such studies be carried. out in cooperation with a trained psychiatrist, who should possess 0f much knowledge as possible about the drug’s actions and side effects, and the methods used to alleviate or counteract them in case any emergency should arrive.”

“This physician,” according to DiMascio, “should be available on call and in the building in which the experiments are being carried out, since it has been shown that the drug’s actions may alter both the physical and mental processes of an individual,”

Several months later, Leary initiated a new conflict with the administration. When, in the winter of 1962, the University attempted to stem undergraduate drug use on campus, Leary and Alpert increased their efforts to broadcast a pro-drug message. They chose the wrong message at the wrong time for an administration increasingly anxious about drugs and even the appearance of impropriety. – R. Wasserman

In a November 1962 Crimson article, Dean of Harvard College John Monro and Director of UHS Dana Farnsworth warned students about the dangers of drug use.

Boston Globe ‘heats’ the Oven

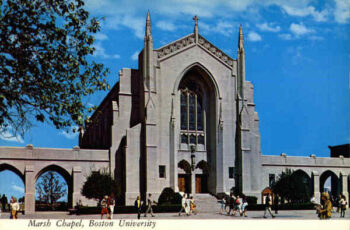

The Good Friday Experiment – April 1962

The Marsh Chapel Experiment (a.k.a. “the Good Friday Experiment”) was run by Walter N. Pahnke, a graduate student in theology at Harvard Divinity School, under the supervision of Timothy Leary and the Harvard Psilocybin Project. The goal was to see if in religiously predisposed subjects, psilocybin (the active principle in psilocybin mushrooms) would act as reliable entheogen. The experiment was conducted on Good Friday, 1962 at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel. Prior to the Good Friday service, graduate degree divinity student volunteers from the Boston area were randomly divided into two groups. In a double-blind experiment, half of the students received psilocybin, while a control group received a large dose of niacin. Niacin produces clear physiological changes and thus was used as a psychoactive placebo. In at least some cases, those who received the niacin initially believed they had received the psychoactive drug.

Andrew Weil gave Harvard President Nathan Pusey the ammunition to get rid of Leary and Alpert. Weil, had wanted to volunteer as one of the psilocybin research subjects, but was rejected because Leary and Alpert had agreed to give the powerful mushroom pills only to graduate students, not undergraduates. But Weil became jealous when he learned that one of his undergraduate dorm mates, Ronnie Winston, had been let into the fold by Professor Alpert. At the time, Alpert was a gay man living in the closet. He would later admit that a romantic infatuation for the undergraduate clouded his judgment. Andy Weil went to Ronnie Winston’s father, the celebrated jeweler Harry Winston, and threatened to publish his son’s name in an expose he was writing for the Harvard Crimson—unless Ronnie would inform on Professor Alpert. So, under pressure from his father, Andy Weil and the Crimson, Ronnie was called into the dean’s office and asked, “Did you take drugs from Professor Alpert.” “Yes, sir, I did,” Ronnie confessed, “and it was the most educational experience I’d had at Harvard.” Alpert, a professor on tenure. – Timothy Leary’s Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research, Don Lattin

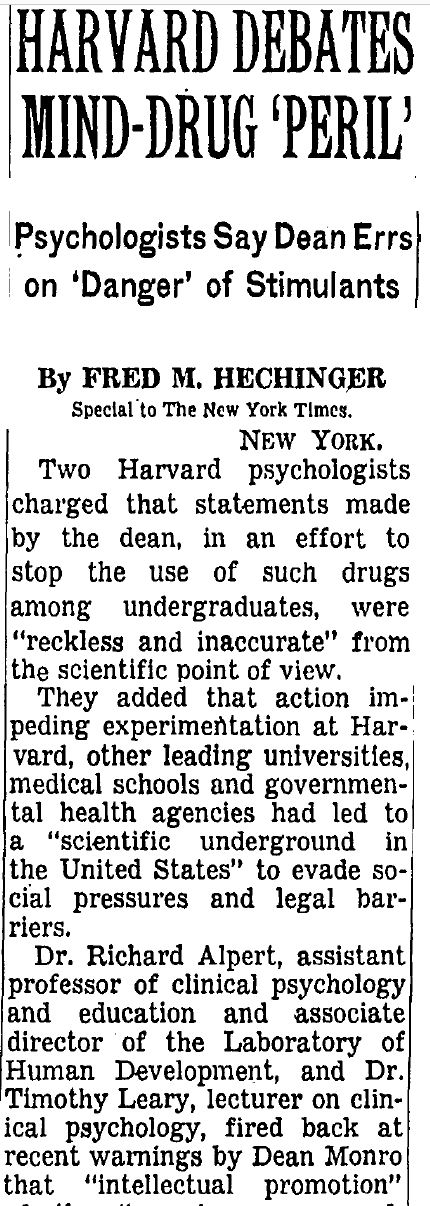

New York Times, December 14, 1962

HARVARD DEBATES MIND-DRUG ‘PERIL’

Psychologists Say Dean Errs on ‘Danger’ of Stimulants

By FRED M. HECHINGJER Special to The New York Times.

Two Harvard psychologists charged that statements made by the dean, in an effort to stop the use of such drugs among undergraduates, were “reckless and inaccurate” from the scientific point of view.

They added that action impeding experimentation at Harvard, other leading universities, medical schools and governmental health agencies had led to a “scientific underground in the United States” to evade social pressures and legal barriers.

Dr. Richard Alpert, assistant professor of clinical psychology and education and associate director of the Laboratory of Human Development, and Dr. ‘Timothy Leary, lecturer on clinical psychology, fired back at recent warnings by Dean Monro that “intellectual promotion” of the “consciousness-expand- drugs constituted a serious hazard among students. The dean termed the drugs “mind distorting.”

Most prominent among these drugs is psilocybin. Others are known as mescaline and LSD.

Dean Monro acted with the full support of Dr. Dana L. Farnsworth, director of the Harvard’s health services and a noted medical authority. The dean said there was “unanimity among our doctors that these drugs are dangerous” and might lead to serious mental illness.

These statements were challenged by the two psychologists in a letter to The Harvard Crimson which ’also had published the earlier warnings. They said that the “hysteria” about the effects of “consciousness-expanding” drugs constituted a danger to scientific research.

Effect Held to Be Mild

While conceding that Dean Monro had an administrative responsibility “to pacify worries about undergraduates’ activity,” the psychologists charged that he was “ill-formed1 about the effects of these drugs.”

Dr.’s Alpert and Leary described the changes produced in the mind by the “consciousnessexpanding” drug as similar to those produced in the mind by the printed word or by the power of suggestion. They said that there was “no factual evidence that ‘consciousness-expanding’ drugs are uniquely dangerous and considerable evidence that they are safe and beneficial.”

They said in their letter to the student newspaper that “there is no reason to believe that consciousness-experiences are any more dangerous than psychoanalysis or a four-year enrollment in Harvard College.”

The psychologists charged that “if you try to apply these potentials within the conventional institutional format you are side-tracked, silenced, blocked or fired.” They said that “competent and recognized scientists” were being barred from such research “not only at Harvard but in the top universities and medical schools in the country and in the United States Institute of Public Health.”

This they added, had “for the first time in American history” led to “a scientific underground.”

Last year, the Massachusetts Public Health Department ruled that psilocybin Is to be administered only in the presence of a medical doctor.

Published: December 14, 1962

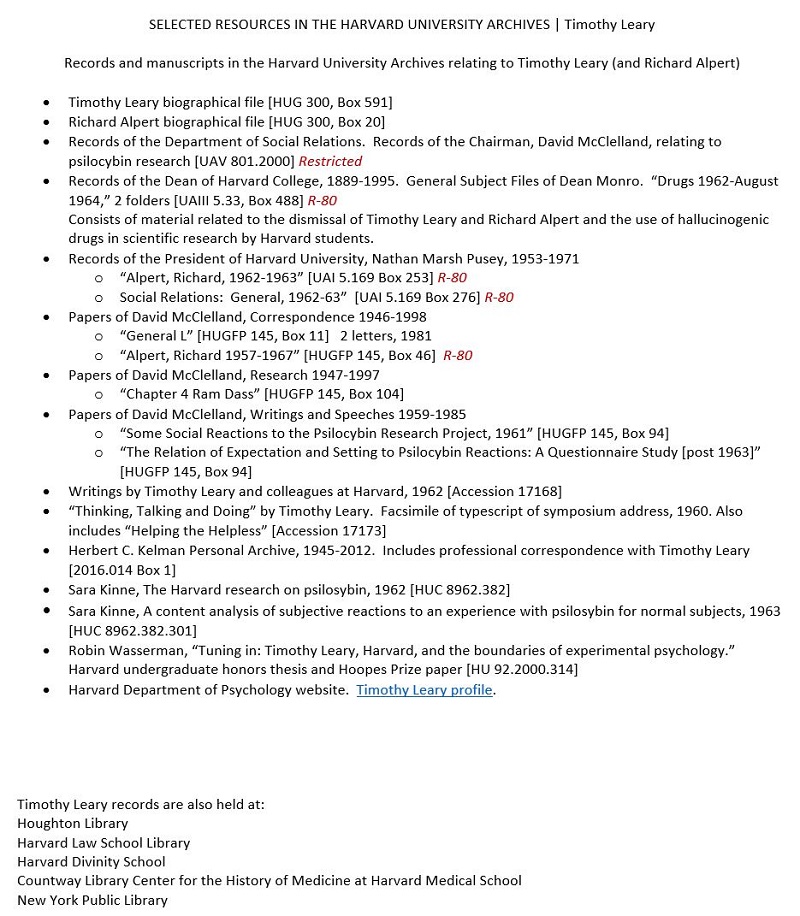

The International Foundation for Internal Freedom

November 1962

Because of the Psilocybin Project’s failure to follow the established scientific method in regards to psychological experimentation, colleagues in the Department of Social Relations at Harvard raised serious questions as to the validity of Leary and Alpert’s work. In an attempt to capitulate to the demands of the Harvard faculty and administration, Leary and Alpert created the non-profit International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in order to separate the scientific research of the Psilocybin Project from the mystic-religious research being conducted outside of the clinical setting.

In November 1962, Leary, Alpert, and 9 other academics formed the International Federation for Internal Freedom. The group’s stated purpose was to encourage people to form research groups to explore consciousness and promote psychedelics research. But the implicit purpose was the democratization of psychedelics—the idea that everyone should be given the opportunity to expand their consciousness using the drugs.

Statement of Purpose of theINTERNATIONAL FEDERATION

FOR

INTERNAL FREEDOM

- The Situation

As long as men have reflected about their world — which is to say for about 3000 years — a basic issue has divided them. There have been those who regard man’s normal conceptual models as straightforward mirror reflections of the way things actually are. Over against them have been men who suspect that these models are more like reducing valves imposed by finite consciousness upon an infinite evolving reality to reduce it to manageable proportions. The issue is whether the world of normal sense is unqualifiedly real and, indeed, the only reality, or whether reality is far more than mind and sense disclose, not only quantitatively, but qualitatively as well. That things are what they seem, and that they aren’t — this has been the great divide that has separated men since they first became philosophers.

What induced those in the second group to fly in the face of sense evidence and assert that things are in truth dramatically different from the way they appear? Reason doubtless played a part, but its speculations must have appeared pale compared with the full-bodied testament of direct experience. For as far back as men have left records, there have been some who reported visions and theophanies in which the’ veils were lowered, the masks of God removed, and reality disclosed with startling force.

It may be that all these tell-tale rents in the fabric of normal awareness involved alterations in brain chemistry, however effected. What we know is that experiences strikingly like those reported by mystics, seers, and visionaries of the past can be created by chemical means. This puts us in the position of being able for the first time to explore experimentally the momentous question of the absoluteness versus the relativity of our sense perceptions and the prevailing conceptual schemes which order our experience.

continue reading >>>

This new organization was not welcome by all.

“Tim, I am convinced you are heading for very serious trouble if your plan [for IFIF] goes ahead as you described it to me, and it would not only make a great deal of trouble for you, but for all of us [researchers], and may do irreparable harm to the psychedelic field in general.”59 Stolaroff’s comment hints at the feared pollution effect of Leary’s psychedelic democratization; he suggests that Leary’s approach had the potential to cause problems not just for Leary but “for all of us.” – Myron Stolaroff

In 1960, Stolaroff established the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park, a non-profit medical research organization. He served as its president until 1970

On Monday December 10, 1962 Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert sat down to write a scathing rebuke in the “Letters to the Editor” section of the Harvard Crimson. Leary’s attempts at research into psychedelics, psilocybin and LSD specifically, had come under fire from the administration of the school. Leary and Alpert were angered at the use of inflammatory language that the dean had recently used in a warning he had issued to the students at Harvard. Leary and Alpert claimed that if you want to test the “potentials [of psychedelic drugs] within the conventional institutional format you are sidetracked, silenced, blocked, or fired.”

On December 9th 1962 the Harvard Crimson foreshadowing the maelstrom of anti-psychedelic articles in national print media, an article was published that asserted Leary and Alpert were being investigated by the FBI and the FDA.

The United States’ Print Media and its War on Psychedelic Research in the 1960s – Jessica Bracco

Leary and Alpert Attack Monro Stand

On Drugs

Offer Defense of Research in Psilocybin, Call University’s Position ‘Ill-Informed’

NO WRITER ATTRIBUTED

December 11,1962

In a statement issued last night in response to questions asked by the CRIMSON, Timothy Leary discounted reports of widespread undergraduate use of psilocybin and similar drugs. “Unfounded rumors about consciousness-expanding drugs have been at fever pitch for the last two years. . .Locally and nationally there seems to be intense interest in consciousness expansion, but little access to the drugs”

However, Leary and Alpert did not join Dean Monro in warning undergraduates to steer clear of the drugs. When asked whether he thought Monro’s warning was out of place, Leary stated: “We understand Dean Monro’s desire to pacify worries about undergraduate activity, but we believe he is ill-informed about the effects of these drugs”.

Letter from Alpert, Leary

(Following is the full text of the letter submitted to the CRIMSON Monday by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert.)

To the Editors of the CRIMSON:

In three recent CRIMSON articles (widely reprinted in the national press) Harvard administrators have stated, that consciousness-expanding drugs (LSD, mescaline, psilocybin) are “a serious hazard to the mental health and stability even of apparently normal people.” While these statements are conservative from the administrative point of view, they are reckless and inaccurate from the scientific. The published facts and the philosophical-political implications deserve thoughtful review. To understand the importance of this issue, it is necessary to realize that more is involved than the more handlings of drugs. What is in question is the freedom or control of consciousness, the limiting or expanding of man’s awareness. Let us consider some of the facts.

These drugs are powerful nonverbal mind-altering substances–probably the most powerful ever known to man. Now any stimulus, verbal or nonverbal, which presents itself to the nervous system changes the bio-chemistry of your nervous system. If you want to play the labelling game you can call some of these changes dangerous and others beneficial. You can label some artificial and others natural. Compare this to the written word. Can the written word be dangerous? Is the written word natural? Are nonverbal stimuli such as the sacred mushroom of Mexico artificial? Is the chemical essence of the mushroom dangerous? Continue reading >>>

The rumors of the past two years, culminating in the publicity of last spring, have made it clear that these materials are too powerful and too controversial to be researched in a university setting. Like other researchers in the field, we have found it necessary to form our own independent research association. Our project has been in continuous operation under medical supervision, and within the framework of the state and federal laws.

I.F.I.F. Group Plans Center For Research

Drug Experimenters To Work in Mexico

The International Foundation for Internal Freedom, an organization to study consciousness-expanding drugs, is arranging to purchase a hotel in Mexico as an international research center.

The foundation applied for incorporation two weeks ago, Timothy F. Leary, lecturer in Clinical Psychology, said, and is studying plans to set up IFIF centers here and in other cities across the country. These centers will study the effects and possible uses of consciousness expanding drugs, he said.

Leary, one of the founders of IFIF, also announced that his connections with the University will end in June, but that his associate, Richard Alpert, assistant professor of Clinical Psychology and of Education, will remain at Harvard next year. Leary said his own plans include writing and working on the two journals which IFIF will publish.

The research of Leary and Alpert into the effects of psilocybin, a hallucinogenic drug, first became a subject of public controversy last spring. At that time other members of the Center for Research in Personality questioned the propriety of the research methods of Leary and Alpert.

This fall, Dean Monro and Dana L. Farnsworth, Director of University Health Services, revived the controversy in an open letter warning undergraduates of the dangers of “mind-distorting drugs.” The letter, widely reported, did not mention Leary or Alpert, or the Center for Research in Personality.

Psilocybin is a chemical synthesis of the active component in a Mexican mushroom which is used in Indian magic rites.

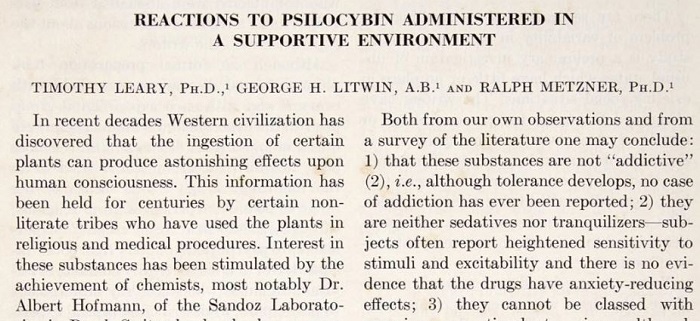

Published in Scientific Journals – December, 1963

REACTIONS TO PSILOCYBIN ADMINISTERED INA SUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENT

TIMOTHY LEARY, Ph.D.,1 GEORGE H. LITWIN, A.B.1 and RALPH METZNER, Ph.D.1

In recent decades Western civilization has discovered that the ingestion of certain plants can produce astonishing effects upon human consciousness. This information has been held for centuries by certain nonliterate tribes who have used the plants in religious and medical procedures. Interest in these substances has been stimulated by the achievement of chemists, most notably Dr. Albert Hofmann, of the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, who have succeeded in synthesizing the active agents in these plants. Among these the best known are the peyote cactus, from which mescaline is derived, the mushroom psilocybe mexicana, the South American vine yage or caapi, and the seed of ololiuqui, also from Mexico. LSD-25, an ergot derivative, is an artificially synthesized substance with properties and effects similar to these others. The substance used in a recent study is psilocybin, a synthetic of the Mexican “sacred mushroom” introduced to Americans by the mycologist R. Gordon Wasson. The active ingredient, psilocybin, was synthesized by Dr. Hofmann (6, 11).

The physiological action of these drugs is not well understood, although some investigators have suggested that the common biochemical denominator may be the indole nucleus, which is found in most of these drugs and is also in serotonin. Elkes (5) provided an excellent review of the relevant literature.

1 Center for Research in Personality, Harvard University, Cambridge. Massachusetts. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Carl Henze and Mr. Sidney Gimpel of Sandoz Laboratories, which supplied psilocybin, and to Richard Alpert, Gunther Weil, Sheila Sostek and Mrs. Pearl Chan for their cooperation and help. This project was supported in part by grants from the Uris Brothers Foundation and from the Laboratory of Social Relations, Harvard University.

Both from our own observations and from a survey of the literature one may conclude: 1) that these substances are not “addictive” (2), i.e., although tolerance develops, no case of addiction has ever been reported; 2) they are neither sedatives nor tranquilizers subjects often report heightened sensitivity to stimuli and excitability and there is no evidence that the drugs have anxiety-reducing effects; 3) they cannot be classed with energizers or stimulants, since although there is increased sensitivity there is usually a reduction in task-oriented energy, and subjects often sit very quietly. Although some investigators (e.g., 1) have classified these drugs as “psychotomimetic” (i.e., as inducing “model psychoses”), others have reported that “mystical” or “religious” experiences are produced (e.g., 11). It is clear from these disagreements that attempts at strict categorization of the effects of these materials are premature. It is the present hypothesis that the attitude of the experimenter toward the subject matter is an important variable. It influences the expectation or set which he communicates to his subjects, and it determines what kind of setting he provides for the ingestion of the drug; these in turn have marked effects on the nature of the experience.

Most investigators would, however, agree to the statement that these drugs alter consciousness. The purpose of the present research was to investigate some of the ways in which consciousness may be altered. The two major practical difficulties in carrying out such an inquiry are 1) the role of set and suggestion, mentioned above, and 2) the fact that both everyday and scientific language are extremely inadequate for describing altered states of consciousness.

March 29, 1963

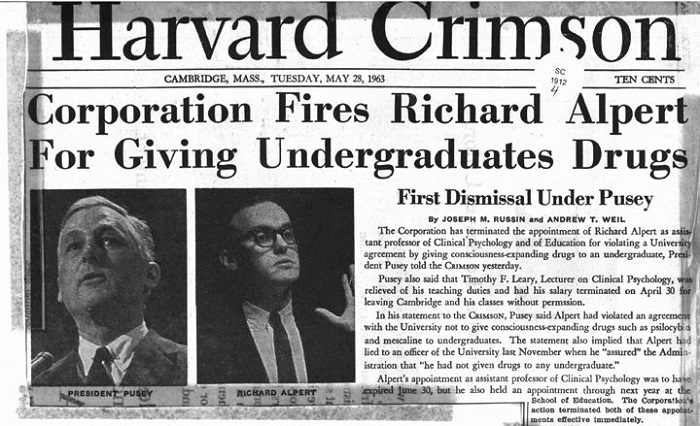

May 28, 1963

The firing of Leary and Alpert from Harvard is often portrayed as having been the result of an article in the Harvard Crimson student newspaper by Andrew Weil, a student at Harvard at the time who later became one of Harvard’s psychedelic researchers. Early 2010 articles in the New York Times about Don Lattin’s book The Harvard Psychedelic Club are a prime example of this. Fact is, that the May 28, 1963 article of Andrew Weil [158] had nothing to do with the firing of Leary and Alpert. Leary was already gone and Alpert was cleaning out his office while this article was published. As the previous section makes clear, both men had been drawing the ire of various influential Harvard professors since at least May 1961.

An Editorial

It would be unfortunate if the firing of Richard Alpert led to the suppression of legitimate research into the effects of hallucinogenic compounds. Such drugs as mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD may be of real value in scientific studies of the mind and in the treatment of mental disorders. But it would have been equally unfortunate if Dr. Alpert had been allowed to continue his activities under the aegis of a University that he has misinformed about his purposes.

His claim to be a disinterested scientific researcher is itself debatable; from the very first, he and his associate, Timothy F. Leary, have been as much propagandists for the drug experience as investigators of it. They are so convinced of the benefits of these drugs that they have dispensed with many normal research procedures; for example, they have conducted some of their experiments in highly informal settings. They have been lax about screening potential recipients of the drugs; indeed, they have urged many who have expressed a casual interest in the drugs to try them for themselves. Far from exercising the caution that characterizes the public statements of most scientists, Leary and Alpert, in their papers and speeches, have been given to making the kind of pronouncement about their work that one associates with quacks.

The shoddiness of their work as scientists is the result less of incompetence than of a conscious rejection of scientific ways of looking at things. Leary and Alpert fancy themselves prophets of a psychic revolution designed to free Western man from the limitations of consciousness as we know it. They are contemptuous of all organized systems of action–of what they call the “roles” and “games” of society. They prefer mystical ecstasy to the fulfillment available through work, politics, religion, and creative art. Yet like true revolutionaries they will play these games to further their own ends. And even more like revolutionaries, they have not hesitated to break the rules of these games when it has suited their ends. They have not been professors at Harvard–they have been playing “the professor game,” and their cynicism has led them to disregard University regulations and standards of good faith. They have violated the one condition Harvard placed upon their work: that they not use undergraduates as subjects for drug experiments.

In general, they have feigned adherence to “the science game” only to give a veneer of respectability to practices antipathetic to the ethics of a university. These practices are not random lapses; they stem from a philosophy that denies the intellectual and moral premises on which a university is based. Universities are built on traditions of open-mindedness, intellectual discipline, and precision of thought and expression. Leary and Alpert show no devotion to these things.

In tacit recognition of the incompatibility of their work with a university environment, they have established a private organization–the International Foundation for Internal Freedom. Leary has already left the University to devote his full energies to this group, and Alpert had also planned to spend much of his time with the Foundation during his year at the School of Education.

Dr. Alpert’s dismissal should not be construed as an abridgment of academic freedom. The University has supported his researches and has been more than reasonable in the precautions it has asked him to take. In dismissing him, it reacted to wilful repudiation of these safeguards. But surely the University has not taken this exceptional step in response to mere misdemeanors. In firing Richard Alpert, Harvard has dissociated itself not only from flagrant dishonesty but also from behavior that is spreading infection throughout the academic community.

The End and Beginning

Harvard professors were not on the sidelines with all of this. Professors Herbert C. Kelman, Henry K. Beecher, and Harry (Henry) Murray (all of whom had done LSD experiments) were vocal opponents which eventually lead in May to the firing of Professor Richard Alpert and the dismissal of Timothy Leary as a researcher.

Alpert’s Response

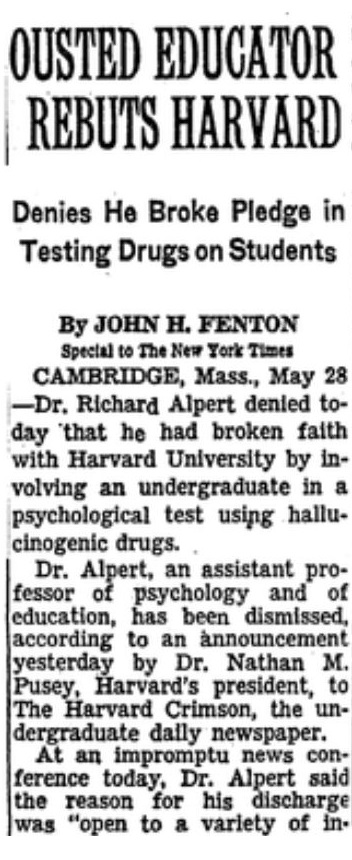

OUSTED EDUCATOR REBUTS HARVARD

Denies He Broke Pledge in Testing Drugs on Students

By John H. FentonSpecial to The New York Times

CAMBRIDGE, Mass., May 28, 1963

-Dr. Richard Alpert denied today that he had broken faith with Harvard University by involving an undergraduate in a psychological test using hallucinogenic drugs.

Dr. Alpert, an assistant professor of psychology and of education, has been dismissed, according to an announcement yesterday by Dr. Nathan M. Pusey, Harvard’s president, to The Harvard Crimson, the undergraduate daily newspaper.At an impromptu news conference today, Dr. Alpert said the reason for his discharge was “open to a variety of interpretations.” Harvard, he declared, “has chosen one which technically justifies their action and which effectively closes off our association with them.”

A months ago Dr. Timothy F. Leary, a lecturer on clinical psychology, was dismissed for his part in the same experiment. He now heads an organization known as the Internation Foundation for Internal Freedom. Dr. Alpert is a director of the foundation.

Dr. Leary was reported today to be in Mexico performing various experiments in the drugs, which Dr. Alpert described as causing “consciousness extension.”

The drugs are psilocybin, mescaline and lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD.

Dr. Alpert said he used psilocybin on one undergraduate a year ago. He said he and Dr. Leary had turned down 200 requests from undergraduates to participate in the research.

“My statement to Dean [John B.] Monro reassuring him that our interest was not in pursuing research among undergraduates,” said Dr. Alpert. “I do not feel that this single exception constitutes bad faith on our part.”

the university had allowed the experiments on the condition that no undergraduate would be used to test the drugs without clearance from a staff member of the university medical services.

In his statement to The Crimson, Dr. Pusey said Dr. Alpert had assured Dean Monro that he had not given drugs to any undergraduate.

In a letter to Dr. Pusey, written since the Harvard Corporation voted his dismissal on May 20, Dr. Alpert said he and his associates had worked “safely” on more than 400 subjects, in prisons, among religious community members in Cambridge and amount graduate students at the university.

An Editorial

It would be unfortunate if the firing of Richard Alpert led to the suppression of legitimate research into the effects of hallucinogenic compounds. Such drugs as mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD may be of real value in scientific studies of the mind and in the treatment of mental disorders. But it would have been equally unfortunate if Dr. Alpert had been allowed to continue his activities under the aegis of a University that he has misinformed about his purposes.

His claim to be a disinterested scientific researcher is itself debatable; from the very first, he and his associate, Timothy F. Leary, have been as much propagandists for the drug experience as investigators of it. They are so convinced of the benefits of these drugs that they have dispensed with many normal research procedures; for example, they have conducted some of their experiments in highly informal settings. They have been lax about screening potential recipients of the drugs; indeed, they have urged many who have expressed a casual interest in the drugs to try them for themselves. Far from exercising the caution that characterizes the public statements of most scientists, Leary and Alpert, in their papers and speeches, have been given to making the kind of pronouncement about their work that one associates with quacks.

Alpert’s Dismissal

The dismissal of Leary and Alpert marked the first time a Harvard professor had been fired in over a hundred years. Nathan Pusey, the president of Harvard, personally conducted a closed-door investigation that included the interrogation of various undergraduate students who allegedly had taken psychedelic drugs with Leary and Alpert. Pusey’s investigation yielded only one confession. Ronnie Winston, a male undergraduate, admitted to taking psilocybin pills with Professor Alpert during the spring semester of 1962. Winston, heir to the Harry Winston jewelry fortune, famously remarked to the President of Harvard: “It was the most profound experience of any of the courses that I have had here [at Harvard]” (Dass and Metzner 90). Pusey’s investigation also uncovered a clandestine affair between Alpert and Winston.

In public accounts of the scandal, Harvard authorities carefully sup-pressed all references to the homosexual affair and fired Alpert for giv-ing psilocybin to “one undergraduate.” President Pusey’s press release on May 27, 1963, states that “ . . . Dr. Alpert violated an agreement which he had entered into in November, 1961, not to involve undergraduates.

Timothy Leary – The Harvard Years, Introduction

Later Alpert “confessed”

“I did break a contract,” (Alpert) said finally.

A year and a half ago I had a very close friend who was a junior at Harvard. I want to keep his name out of this.

He had been having black-market-type experiences with the drugs and they had been pretty lousy.

“I was spending my weekends with him. When you have something and it means something to someone you care about, but you can’t give it to him, it bugs you.

“I gave him a very light dose.

“I had been so good. I turned down over two hundred guys. But my friend had a buddy [Andrew VTeil] who got very irate and went to the authorities.

“Some day it will be quite humorous that a professor was fired for supplying a student with the most profound educational experience in my life.’ That’s what he told the Dean it was.”

Timothy Leary – The Harvard Years, James Penner

Then Came the Nation

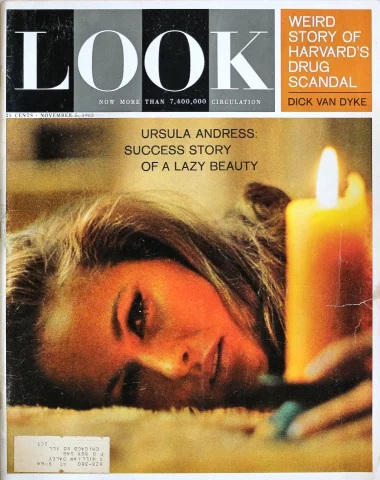

THE STRANGE CASE OF THE

HARVARD DRUG SCANDAL

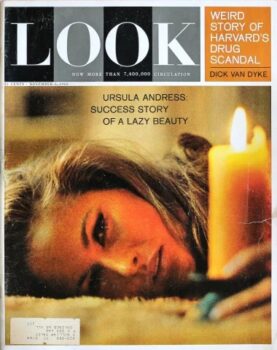

BY ANDREW T. WEIL LOOK MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 5, 1963

A 1963 article in Andrew Weil’s Look Magazine detailed the scandal now erupting.

“Supported by the Harvard Center for Research in Personality, Richard Alpert, with his associate Dr. Timothy F. Leary, a lecturer on clinical psychology, set out to investigate the new drugs. Many scientists had studied hallucinogenic drugs before 1960, but most of them were physicians, interested in determining physiological effects or in using the drugs to reproduce, under laboratory conditions, the symptoms of mental illness. LSD, particularly, was widely employed in the early 1950’s to cause “model psychoses” in normal subjects, and there was some hope that these experiments would point to an understanding of the chemical basis of schizophrenia. Unfortunately, these early efforts produced little new or valuable information. The biochemistry of the drugs remains to be worked out, and the dream of understanding the chemical nature of mental illness has not materialized.”

The Harvard Psilocybin Project Look Magazine – by Andrew Weil

***

Gunther Weil one of the five main participants in the Psilocybin Project, talks in a podcast in 2020 about his time at Harvard

In the meantime, the team is publishing articles in scientific journals.

Journal of Nervous Disorders, 1963

REACTIONS TO PSILOCYBIN ADMINISTERED IN A SUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENT

TIMOTHY LEARY, Ph.D.,1 GEORGE H. LITWIN, A.B.1 and RALPH METZNER, Ph.D.1

In recent decades Western civilization has discovered that the ingestion of certain plants can produce astonishing effects upon human consciousness. This information has been held for centuries by certain nonliterate tribes who have used the plants in religious and medical procedures. Interest in these substances has been stimulated by the achievement of chemists, most notably Dr. Albert Hofmann, of the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, who have succeeded in synthesizing the active agents in these plants. Among these the best known are the peyote cactus, from which mescaline is derived, the mushroom psilocybe mexicana, the South American vine yage or caapi, and the seed of ololiuqui, also from Mexico. LSD-25, an ergot derivative, is an artificially synthesized substance with properties and effects similar to these others. The substance used in a recent study is psilocybin, a synthetic of the Mexican “sacred mushroom” introduced to Americans by the mycologist R. Gordon Wasson. – National Library of Medicine

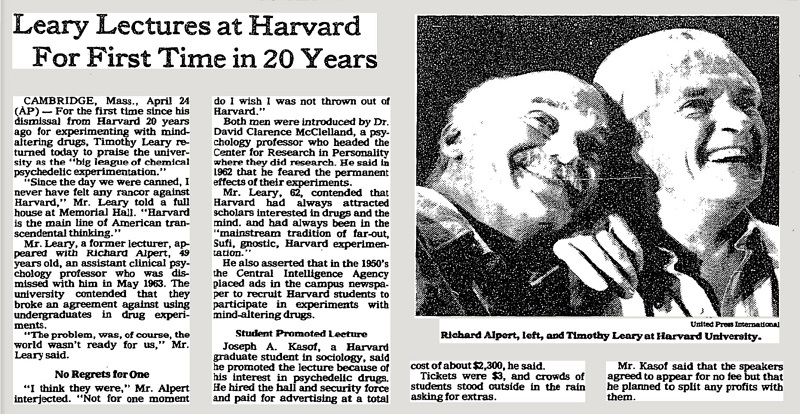

Leary, Alpert Return to Harvard

Short Takes

In 1962. Harvard fired two controversial young psychologists from their Faculty posts following a year of tumult about the pair’s research on LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs.

Tomorrow both men will return to Harvard Timothy Leary whose “turn on tune in and drop out” became the rallying cry for a generation of drugs-users, and Richard Alpert who now goes by the name Ram Dass. The two will speak at Sanders Theater at 10:30 a.m. in an event being billed as a “psychadelic reunion”.

The forum will be moderated by Professor of Psychology David C. McCelland, who chaired the now-defunct Social Relations Department at the time of the controversy.

PUBLISH DATE – April 25, 1983

For the first time since his dismissal from Harvard 20 years ago for experimenting with mindaltering drugs, Timothy Leary returned today to praise the university as the ”big league of chemical psychedelic experimentation.”

”Since the day we were canned, I never have felt any rancor against Harvard,” Mr. Leary told a full house at Memorial Hall. ”Harvard is the main line of American transcendental thinking.”

Mr. Leary, a former lecturer, appeared with Richard Alpert, 49 years old, an assistant clinical psychology professor who was dismissed with him in May 1963. The university contended that they broke an agreement against using undergraduates in drug experiments.

”The problem, was, of course, the world wasn’t ready for us,” Mr. Leary said.

No Regrets for One

”I think they were,” Mr. Alpert interjected. ”Not for one moment do I wish I was not thrown out of Harvard.”

Both men were introduced by Dr. David Clarence McClelland, a psychology professor who headed the Center for Research in Personality where they did research. He said in 1962 that he feared the permanent effects of their experiments. Mr. Leary, 62, contended that Harvard had always attracted scholars interested in drugs and the mind. and had always been in the ”mainstream tradition of far-out, Sufi, gnostic, Harvard experimentation.”

He also asserted that in the 1950’s the Central Intelligence Agency placed ads in the campus newspaper to recruit Harvard students to participate in experiments with mind-altering drugs.

Student Promoted Lecture

Joseph A. Kasof, a Harvard graduate student in sociology, said he promoted the lecture because of his interest in psychedelic drugs. He hired the hall and security force and paid for advertising at a total cost of about $2,300, he said.

Tickets were $3, and crowds of students stood outside in the rain asking for extras. Mr. Kasof said that the speakers agreed to appear for no fee but that he planned to split any profits with them.

PUBLISH DATE April 25, 1983

Andrew Weil, MD on the LSD Scandal

that got Leary and Alpert out of Harvard

Look Magazine, November 5, 1963