Originally published in

The Laughing Man Magazine, Vol 8, NO 1, 1988

The Laughing Man Magazine, Vol 8, NO 1, 1988

hen I was in college in the late 1960s Eastern spiritual ideas rode into the popular mind on a wave of LSD. Drugs, acid rock, and Vietnam had set “the best and the brightest”, and many more besides, adrift from the mainstream, middle-class vision of life. Suddenly possibilities were wide open. In everything the stakes seemed very high, the routes unknown, the opportunities stupendous. Of the many new ideas surfacing at that time – ecological awareness, sexual freedom, communal living, psychedelic drugs, and mysticism, among others – one theme emerged above all to claim the allegiance of those who thought themselves ready to go for broke to find, to know, and to live reality. The theme was ego-death.

hen I was in college in the late 1960s Eastern spiritual ideas rode into the popular mind on a wave of LSD. Drugs, acid rock, and Vietnam had set “the best and the brightest”, and many more besides, adrift from the mainstream, middle-class vision of life. Suddenly possibilities were wide open. In everything the stakes seemed very high, the routes unknown, the opportunities stupendous. Of the many new ideas surfacing at that time – ecological awareness, sexual freedom, communal living, psychedelic drugs, and mysticism, among others – one theme emerged above all to claim the allegiance of those who thought themselves ready to go for broke to find, to know, and to live reality. The theme was ego-death.

“With no one quite knowing how it happened, ego-death became a kind of unquestioned highest value in the burgeoning counterculture.”

With no one quite knowing how it happened, ego-death became a kind of unquestioned highest value in the burgeoning counterculture. It joined the gritty, basement realism of the existential “beat” movement with the exalted aura of sublimity emanating from the practicing mystics. The “truth for truth’s sake” attitude toward life had already been epitomized in Western culture through the hallowed image of the questing poet-outcast, our quasi-religious archetype of the spiritual seeker. The beat poets were willing to nose around any precincts that might reveal and dissolve the contours of the overstuffed, power-driven ego now taking full possession of industrial society. Nobody captured the angst and the motion of the venture better than Alan Ginsberg in his breathless poem of agony and ecstasy “Howl”.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by /madness, starving hysterical naked, /dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn /looking for an angry fix /angel headed hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly /connection to the starry-headed dynamo in the machinery /of night….

The long-running underground river of the beat movement finally met its ocean in 1967 when the social revolution signified by the ‘summer of of love’ accelerated its tempo and transformed its scene beyond what anyone had imagined. ’Beat” now flowered as ‘hippie’ and reached all the way into America s suburban high schools and colleges.

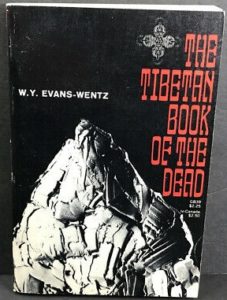

Before long we saw the truly hip ranging college campuses and the burgeoning psychedelic ghettos carrying copies of Evans-Wentz’s translation of ‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead’.1 For those who knew even a little about Tibet, the images suggested by the book and the legends sur-rounding it were rugged mountains, cold, dear, fierce streams, scarce vegetation, and rocky, unpopulated plateaus. The culminating event of ego-death seemed to require the most extreme of situations. We contemplated desolate images of isolated graveyards strewn with the bones of the dying, encircled by vultures waiting to scavenge the remains of yet another heroic meditating soul who yielded his very body to this illusory world in a game exchange for the rewards of Nirvana.

1. W. Y. Evans-Wentz, The Tibetan Book of the Dead (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

Tibet was far away, however, and obviously very uncomfortable to visit, much less die in. Nevertheless, no less a product of my times than anyone else, I was caught up in the motion. I well remember the spring afternoon when I heard that my college had an opening in the Religious Studies Department. With the energetic naivete of youth propelling me, I found my way to the department chairman and excitedly encouraged him to go to India and hire an authentic yogi to help students like me through the death-rebirth process. The department chairman was a typical academic existentialist thinker, a proponent of “the death of God” theology. “I don’t think such an uncredentialed appointment would be likely,” he told me dryly. I quickly realized my cause was hopeless. As I was leaving I noticed that he was digging his knuckles into his desk.

Soon I learned that cheaper help was available closer to home. The recently converted middle-class young like me were clearly as unenamored of the rude living and the trials of suffering endured by the beat subculture as we were daunted by the prospect of a long journey east. It was natural to look for a quicker, more pleasurable route to liberated ecstasy. A chance discovery at the Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, duplicated without sanction by a few prodigious underground chemists, brought the great shortcut, LSD, into our hands. What previously had cost oriental yogis years of preparation and discipline now seemed achievable in a matter of minutes.

“The other day they waited /The sky was dark and faded / And solemnly they stated /He has to die / You know he has to die.”

To our progress-informed minds, the psychedelic trip was Western science’s solution to the wasteful effort of less inventive eras. With a populace well prepared for innovation by modem advertising, it was no wonder that the drug’s messianic distribution through subcultural pathways was so rapid. The artists, of course, tried it first, and soon acid was all over America’s streets. And before long ego-death via LSD appeared in the lyrics of the most magical of the acid-rock bands, The Grateful Dead, whose ‘That’s It for the Other One” intoned “The other day they waited /The sky was dark and faded / And solemnly they stated /He has to die / You know he has to die.” You had to be hopelessly square not to know they were talking about an LSD-induced ego quenching.

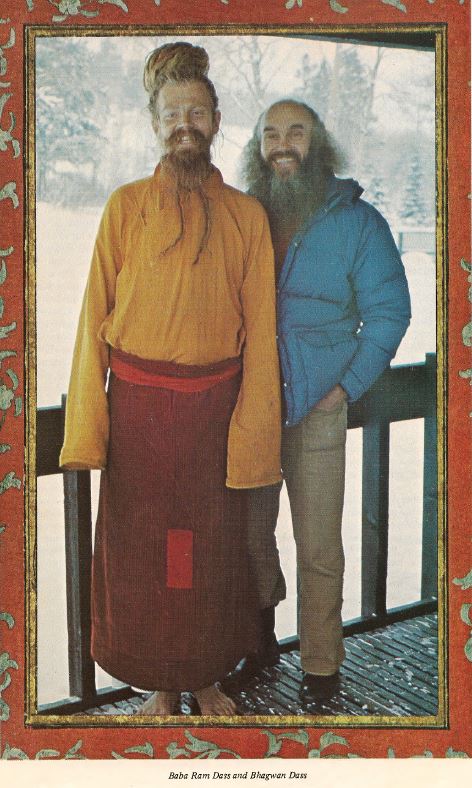

This preparatory work made former Harvard professor Tim Leary’s plucky advertisement for the quick route to ego release via LSD seem all the more attractive and convincing. Timothy Leary and his friends Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (later to become Baba Ram Das to America’s spiritual seekers) translated the venerable Tibetan manual into a more contemporary psychedelic lingo that cut out most of the cosmological “debris” and made the Shining Void seem as accessible as the local movies. Why journey around the world when you can hop a chemically fueled rocket? The more intelligent took the drug seriously and prepared for their voyages with care.

When all was said and done, it has to be admitted that the rewards were real. Despite the genuine risk to one’s comfort and sanity, psychedelic drugs did provide a glimpse of existence that silenced the droning dogmas of scientific materialism. People really did see spirits, feel energies, and enjoy visions and intuitions that definitely showed reality to be a whole lot bigger and more wondrous than the corporations, pundits, and professors were letting on. A few of us even skated through or over our fear to a momentary glimpse of the pristine freedom of egolessness. Everyone had their stories. I certainly had mine.

In September of 1970 I was at my wit’s end, ensnared in a contradiction I couldn’t see my way through. On the one hand I was profoundly concerned with the creation of a just, peaceful, and loving world order. Mass starvations, massacres, ghetto violence, Vietnam, and the other atrocities of the post-World War II West seemed absurdly insane, and I, along with many of my generation, felt that we had to have the vision and the will to end the madness. On the other hand, there was the constant allure of the spiritual, now being served by the accelerated introduction of esoteric oriental teachings into the West. This inspired the happy suspicion that perhaps there was a greater vision, one that would alter the very context of our conflicts so that they could be managed from a whole new perspective.

I was living at the time in Berkeley, California – just coming into its own as a crossroads of the new political and spiritual currents streaming through the United States. Walking down Telegraph Avenue to the University of California campus I often passed through a gauntlet of radicals aggravatedly calling for my support of one or another cause. But inscribed in bold letters on the awning of that street’s spiritual bookstore was the exalted admonition “All Hail the One Cosmic Mind”. I was deeply tom by the apparent contradiction. Politics or mysticism? Justice or Awakening? This world or the next?

“I felt that I could be absorbed into that very Light, which was an original spiritual existence, but that if I did I would never speak my own truth again for the Light would then forever more require my complete discipleship.”

So when a Berkeley friend brought home a container of mescaline fresh from the laboratory of a famed psychedelic alchemist, I decided it was time to get my answer. Only hours later I was walking in the Berkeley hills, my being temporarily transformed by drug-induced glories. I had taken an unreasonably large dose, as if the amount itself would purify and concentrate the issues for me and draw an answer from the depths of being itself. As I climbed the hill I watched the rolling patterns of the windblown grass. Nature seemed a thin veil simultaneously revealing and concealing the rhythmic presence of divinity. I felt my attention drawn to a locus of great power and light that was always somehow above and behind me. I felt that I could be absorbed into that very Light, which was an original spiritual existence, but that if I did I would never speak my own truth again for the Light would then forever more require my complete discipleship.

I even physically withdrew from the ascending impulse, saying to myself that I wasn’t yet ready to make such a gesture. I knew as I refused absorption in this Light that that refusal was a primal act of independent selfhood, that it was egoity itself. Shortly thereafter, I came to another crossroads. A suddenly arising edge of anxiety snowballed into an overwhelming, unstoppable fear that I was going – and indeed had gone – completely mad! The fear moved much faster than my mind’s ability to assert control. With no resorts, I spontaneously surrendered to the fear . . . and fell straight through it out the bottom of my presumed self! In that moment of yielding, everything was lost and won as the groundless freedom of my very Selfhood showed itself. I chuckled at the obviousness of my freedom, the nothingness of what I had moments before held most precious – me.

I sat down on the hillside and gazed at the San Francisco Bay. I could have sat there for an eternity – time seemed to have stopped completely. I did not think; thoughts arose. Then, suddenly, in a moment, it became obvious that everything is a single mind or consciousness. It was a superconscious intuition that could not have been more self-evident. Then a friend came up to me and it was time to leave.

“To our progress-informed minds, the psychedelic trip was Western science’s solution to the wasteful effort of less inventive eras.”

After that I knew that the first office of every life is the attainment of transcendental awakening. However noble and just in itself, the human struggle for right and benign arrangements in this world must occur within the context of that spiritual endeavor and not merely precede it. From there it was a search through the various spiritual resources available to me until I met my Teacher and Master, Heart-Master Da Free John.

What had occurred for me in the Berkeley hills, if not permanent ego-death, was at least the temporary intuition of egolessness. It is certainly not a unique story. Now, nearly twenty years later, I think it’s fair to say that I and the rest of the psychedelic voyagers of my generation have kept our egos. LSD, it seems, may have a message, but it is not a way.

Many illusions popularly surround the whole matter of “ego-death” – our shortsighted and indulgent reliance upon psychedelic drugs being only one of them. Of course a consumer society would happily endorse a path that could be purchased and swallowed like any drugstore remedy. But our real confusions went deeper. They lay in the very attempt to pin the oriental notion of egolessness to the procrustean bed of our Western individualistic culture.

In Turning East, Harvard-based Christian theologian Harvey Cox gives an account of his academic and personal researches into the recent interest shown by Westerners in oriental religion. He points to the fundamental confusion that Americans in particular have about key notions in the Eastern spiritual tradition. Cox identifies “detachment” and “egoless-ness” as the two central tenets of all forms of Buddhism, and proceeds to explain how these were dramatically misinterpreted by a transient modern culture primed to adapt them to its own direction:

Americans already experience a kind of “detachment,” albeit very different from what the Buddhists have in mind. Our detachment comes from our living in a mobile, throwaway civilization in which we are schooled by the media not to get too attached to anything – or anybody – because we will soon have to discard it (or him or her) when an improved model appears. Our American form of detachment comes not from the spiritual insight that all things are moving toward nothingness, but from planned obsolescence, fashion changes, and the constant introduction of new products to replace the ones we have. Our form of “detachment” is a kind of alienation that also infects relationships to persons, not just to things. It is the result of a Kleenex, paper plate and styrofoam cup way of life – itself the result of our economy’s unending need to sell new products.2

2. Harvey Cox, Turning East: The Promise and Peril of the New Orientalism (Touchstone Books, 1979), pp. 137-38.

Cox goes on to say that this confusion about detachment might not be too damaging, were it not combined with a far more fundamental misconception about egolessness itself. Without any true understanding of what Buddhists mean by egolessness Westerners have created their own version of the concept, as Cox explains:

Western religion tends to accept the ego but teaches that love as a positive form of attachment can replace possessiveness and manipulation. Eastern spirituality does not give love such a central place, but teaches that the ego is unreal, and that all forms of attachment lead to suffering. The prism-distorted Western version of Buddhism combines loveless ego with psychological “detachment.” What comes out looks much like irresponsibility with a spiritual cover, a metaphysical license to avoid risky, demanding relationships, a mystical permit to skip from one person, bed, cause or program to another without ever taking the plunge.3

3. Ibid., pp. 139-40

While Harvey Cox tends to settle for a rather Westernized understanding of what oriental cultures have understood as “Enlightenment”, he does have a clear instinct for the way Westerners bend Eastern spiritual exercises to the ego’s own ends. Earlier in the book he observes that, in practice, the search for Eastern-style self-realization results in a mode of living that might be called “concentric” – i.e., focused upon a point within. Da Avadhoota (Adi Da Samraj) has also addressed this disposition, which tends toward meditation on inward states combined with social withdrawal. He observes that excessive concentration upon the internal T only reinforces ego bondage and brings us no closer to the Divine Reality.

Many people . . . hope to Realize Liberation through dissociation. But they must first be relieved from their imaginary disease. In effect they must be cured of their alienation. The signs of their alienation in daily life and in the relational context of their existence must disappear, and in their disappearing, intimacy with the Transcendental Condition will reappear and begin to show its signs in life and in the basic consciousness of existence.4

4. Da Free John, The Fire Gospel: Essays and Talks on Spiritual Baptism (San Rafael, Calif.: The Dawn Horse Press, 1982), p. 23.

From this perspective all forms of introversion only extend and even compound the error that everyone is already making. Our first responsibility is not to become quiet and inward but to understand the whole strategy of interior resort. We transcend the mind by becoming the body. In becoming the body simply we discover ourselves to be much larger than even the mind suspected. This is not merely extroversion. We also become quiet.

“The need for a total culture of practice is irreducible. No one-shot experience or exclusive concentration in one or another kind of esoteric practice or “enlightenment weekend” can excuse us of the creative sacred ordeal requiring the commitment of our entire being. “

My experience in meditation in the spiritual company of Da Avadhoota (Adi Da Samraj) is that when my search for inner peace and quiet is released in real self-understanding, a magnificent sense of expansive well-being as the entire body is awakened. To meditate truly is to be opened at the heart. The sense of freedom, bliss, and power involved in this is completely opposite to that of the usual image of the “cooled-out” meditator, immune in his or her detachment from the play of life. Real understanding and transcendental Realization are not philosophical. They require participation of the whole body-being in a gradual psycho-physical transformation.

While it is true that the vision of ego death propagated in the West through the popularization of Eastern literature is a distortion of the one conceived in the Orient, the oriental notion of ego-transcendence has serious limitations in itself. What it lacks is precisely the dimension to which we have just referred – a healthy and genuinely illumined acceptance of bodily life. The great and authentic Realizers have almost all been Asians, to be sure, but they themselves exceeded their typically ascetical, other-worldly cultural milieu, which tends to equate egoic consciousness with bodily existence and to devalue manifest life as merely “samsara”, or “maya” (illusion).

Overcoming the reaction to incarnate life is not to make bodily fulfillment in life a spiritual value, as we like to do in the West. Rather, it is to understand that the Western cultural and religious emphasis upon incarnation and the opposite Eastern cultural and religious movement toward what we might call ” excarnation” both express a more fundamental reaction to the mere fact of our mysterious embodiment. The Enlightened man or woman enjoys what Da Avadhoota (Adi Da Samraj) calls “mindless embodiment”, in which the body and every other apparent object is seen to be nothing more than a modification of conscious light. From that position we are free of the opposition of “for” and “against” (or yes and no) of West and East, and released into a free play with existence as the body only (which is mere Consciousness Itself) in which nothing remains to be accomplished or escaped.

Da Avadhoota (Adi Da Samraj) points out that instead of trying to suppress our incarnate life – as if mere existence were the error – we need to allow the native force of life to reach beyond its presumed limits and extend outward to infinity. His Teaching is about complete association or participation in life, not withdrawal. It is for this reason he has characterized his own quality as one of “boundless extroversion”.

Such an uncompromising embrace of incarnate existence demands an outgoing or life-based practice. This is exactly what we did not reckon with during the euphoric sixties when so many of us attempted to make off with merely the results or apparent rewards promised in the oriental teachings, without the hard work. And yet it is understood in every traditional religious school that the unregenerate beginner must first be turned out of his self-reliant individualism (what used to be called “worldliness”) to an actual encounter with and dependence upon the Living Divine. By whatever name you call it, it is this Reality and not merely our own egocentric efforts that purifies and uplifts us. This turnabout or conversion necessarily offends our willful self-possession and presumed self-sufficiency. It is therefore very difficult to accomplish. We are required to change our behavior in every precinct of our lives, since our chronic patterns are the daily script of our egoic program.

So, as real religious practitioners, we change our diet, study sacred scriptures, serve our Teacher and the temples he or she has established, pray or meditate, practice the appropriate sacraments, give money and other offerings to our school, accept disciplines of speech and dress, temper our usual commerce with ordinary entertainments and friends, accept direction from those more mature than ourselves and from the teachings whose authority we have come to trust, etc. These disciplines are all designed to turn us from the habitual self-indulgence and self display that constitutes daily life for nearly all men and women, to the acknowledgement of and homage to the greater Reality we say we wish to know and love.

The breaking down of the psychophysics of our ego by these very functional means is what true religion accomplishes. It is a humble purification and rededication of our character that supplies the missing link necessary for us to make a genuine transition from our television upbringing to the profundity of the process that leads to ego-death. Those who try to bypass this transitional step inevitably fail at spiritual life altogether. For this reason Heart-Master Da Free John points out that before we can fully realize our inherent identity with God (ego-death) we must first realize our relationship to and dependence upon Divine Grace. In his own language, before we can be “liberated” we must first be “saved”. The alienated ego cannot take Heaven by storm. Rather, it must acknowledge its own situation and first patiently serve the Divine until its alienation is replaced by Divine Communion. This preparatory work (which may take years to fulfill) has nothing to do with negating the basic force of the being. It is the release of that force from limiting identification with the body-mind. On this foundation, ego-death, expressed by Da Avadhoota (Adi Da Samraj) as “Ecstasy, or the Realization of Love” becomes a possibility.

The need for a total culture of practice is irreducible. No one-shot experience or exclusive concentration in one or another kind of esoteric practice or “enlightenment weekend” can excuse us of the creative sacred ordeal requiring the commitment of our entire being. The religious, spiritual, and meditative way of Truth or Eternal Life is a process of personal, moral, and higher psycho-physical sacrifice. It is not a superficial and private remedial technique but a form of culture, a profound and total way of life.

The message is this: You, as you know or may experience yourself, are not immortal, nor yet even fully human. What you tend to be, and think, and live is exactly what must be overcome – through insight, change of action, and the fullest working out of the disposition of sacrifice. Your reluctance to resort to the Divine and to the higher Agency of the Spiritual Master, neither of which is within you or even merely outside you, is a sign of the very dilemma from which you must be liberated. Your moral and relational weakness or reactivity is the dominant fault that binds you to the illusion and torment that is yourself. Your tendency toward confinement in inward and mental and physically self-possessed states is not at all reinforced by the truly spiritual Way. The entire Way of Truth is immensely difficult and creative. The entire Way is a Sacrifice. The Way of Truth is the only matter of ultimate significance in the life of Man. Let us yield our very bodies and minds into the Reality and Destiny that is both Spirit and Truth.5

5. Da Free John, Scientific Proof of the Existence of God Will Soon Be Announced by the White House! (San Rafael, Calif.: The Dawn Horse Press, 1980), p. 33.