Epidemics, War, and Peace

An exploration of the nature and origin of epidemic diseases, its relationship to the politics of war and peace, and how it informs our philosophical-clinical orientation.

This essay was written in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, exploring the relationship between epidemics and war. Given the horrors of the ongoing warfare in Ukraine and now in Gaza, the shared context of epidemics and war felt like a timely topic to consider further. I have since revised the essay significantly, in expansion of the original themes and in light of current events.

Epidemic diseases are a multi-faceted phenomenon that have plagued humanity for thousands of years; shaping history, medicine, and culture in its movements. In this five-part essay, we will explore the historical origins of epidemic diseases in agrarian contexts, a timeline of epidemic diseases from 430 B.C.E. into the present, the connection between epidemics and war, Chinese and Tibetan etiologies of epidemic disease, and a vision for a healthy and peaceful future.

I. Etymology, Agriculture, and the Emergence of Community

The word epidemic traces its etymology to two Greek words—epi meaning “upon” and dēmos meaning “the people”. The Greek epidēmios means “prevalent” and the later evolute epidēmia means “prevalence of disease”. The New Oxford Dictionary defines epidemic as, “a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease in a community at a particular time”. When an epidemic spreads across regional borders and becomes an international phenomenon, it is known as a pandemic—from the Greek pandēmos (pan means “all” and dēmos means “people”).

In all the aforementioned meanings, “community” emerges as a theme. There can be no epidemic outbreak without a community of people—and the origins of human community traces to the beginning of agrarian life. According to anthropologists, contagious diseases existed during the early hunter-gather period of human evolution, but these diseases never reached epidemic proportions due to their nomadic lifestyle. Historians postulate that epidemic diseases formed alongside communities, which began in earnest with the advent of agriculture roughly 10,000 years ago.

Jared Diamond, an American scientist and professor, considers agriculture to be “the worst mistake in the history of the human race”.12 In an essay bearing this title, Diamond echoes the idea that necessity is the mother of invention, positing that hunter-gatherers began farming in order to feed a growing population. Diamond notes that agriculture had dire consequences on human health, resulting in “malnutrition, starvation, and epidemic diseases”.3 In particular, Diamond states that farming led to a less varied diet, compromising nutrition via dependence on starchy crops that were limited in number—the result being malnutrition and starvation when crops failed. Diamond is clear that increasing population numbers and resultant urbanization led to the formation of epidemic diseases that were absent during the nomadic lifestyle of hunter-gatherers. Diamond writes:

. . . the mere fact that agriculture encouraged people to clump together in crowded societies, many of which then carried on trade with other crowded societies, led to the spread of parasites and infectious disease. (Some archaeologists think it was crowding, rather than agriculture, that promoted disease, but this is a chicken-and-egg argument, because crowding encourages agriculture and vice versa.) Epidemics couldn’t take hold when populations were scattered in small bands that constantly shifted camp. Tuberculosis and diarrheal disease had to await the rise of farming, measles and bubonic plague the appearance of large cities.4

Diamond also notes the socio-political impact of agriculture: class divisions. The arising of class divisions is the seed of war, and we will soon see that war and epidemics are inextricably linked. Diamond reaches a similar conclusion:

Archaeologists studying the rise of farming have reconstructed a crucial stage at which we made the worst mistake in human history. Forced to choose between limiting population or trying to increase food production, we chose the latter and ended up with starvation, warfare, and tyranny.5

II. A Timeline of Epidemics: 430 B.C.E. to 2023

The first record of a pandemic dates to 430 B.C.E. in Athens, Greece during the Peloponessian War. The epidemic disease (now speculated to have been typhoid fever) crossed the borders of Libya, Egypt, and Ethiopia during the Spartan seige—leading to defeat in Athens and the death of two-thirds of the population.6

The next record of a pandemic occurs 594 years later in 165 A.D. with the Antonine Plague. Speculated to be an early occurrence of smallpox, the disease spread from the Huns to the Germans and finally to the Romans during the Roman seige of Seleucia. Returning troops spread the disease throughout the Roman Empire, marking the onset of a plague that would last until 180 A.D. Here, we see again the origin of an epidemic in the context of warfare. In 166 A.D., one year into the Plague, marked the beginning of the Marcomannic Wars—a period of warfare that would last until 180 A.D., the concluding year of the Plague. An estimated 7-8 million people died during the Antonine Plague, including Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 A.D.

The coming centuries saw the occurrence of two more plagues—the Cyprian Plague of 250 A.D. and the Scythian plague of 541 A.D. Remarkably, there is no record of epidemic outbreak until the 11th century leprosy pandemic. From here, we see a trend of epidemic outbreaks every 100-200 years into the present century—the Black Death of 1350; the transmission of smallpox, measles, and bubonic plague by Spanish Invaders in the Caribbean; the near extinction of the Taino people upon the arrival of Christopher Columbus; the fall of the Aztec Empire in 1520 due to an epidemic of smallpox; and the Great Plague of London in 1665.

There is a notable rise in the frequency of epidemic outbreaks in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, with multiple outbreaks occurring in the course of a single century. The 19th century alone saw four epidemic outbreaks—the first Cholera pandemic of 1817, the third Plague pandemic of 1855, the Fiji measles pandemic of 1875, and the Russian Flu of 1889. The 20th century saw the Spanish Flu of 1918, the Asian Flu of 1957, and the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic that was first classified in 1981. This brings us to our present era, the 21st century, which has seen two epidemics in 23 years—the SARS pandemic of 2003 and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic of 2019.7

So far, we have seen how epidemics have influenced human history, from the advent of agriculture to the politics of warfare. The last 100 years alone have been devastated by four different epidemics, a current pandemic, and an increasing likelihood of experiencing more epidemic outbreaks as time goes on. The reasons for this are multitudinous: agriculture not only created a context for contagious transmission via increasing populations, it had an ecological impact that reached a fever-pitch in the modern era with monocropping, the creation of GMOs, and the extensive use of chemical pesticides in farming. These practices are justified as a means to secure food supply and combat starvation. Technological advances have led to concerning developments in this regard, with un-sustainable farming practices becoming a major cause of climate change. Ecological disturbance and chemical proliferation are, in fact, two of the primary etiological factors of epidemic diseases in Asian medical systems, connections we will now explore.

Thank you for reading Somaraja. This post is public so feel free to share it.

III. Yi: Epidemics, War, and Medicine

In an essay published in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Liu Lihong reflected on the linguistic links between medicine, war, and epidemic disease. In doing so, he demonstrated the connection between these three realities and how this understanding is reflected in the pictographic language of classical Chinese. Lihong writes:

The Chinese character for epidemic (yi 疫) consists of the components 疒and 殳. According to the dictionary Definitions of Simple and Complex Pictograms, this character represents a combination of components that respectively indicate the meaning and sound of the word. The component 疒, pronounced ne by itself and signifying disease, expresses the general meaning of the word, while殳, an abbreviated version of the character 役 yi for war, primarily serves to express the phonetics of the word for epidemic, but also expresses more specific layers of the term’s meaning. We can see, therefore, that at least during the period preceding the Eastern Han, epidemic outbreaks were linked to war.8

Lihong continues:

Since all good examples tend to come in pairs, the traditional version of the character 醫 for medicine also includes the component 殳. The fact that the characters yi 醫 for medicine and yi 疫 for epidemic are pronounced the same, moreover, demonstrates that the business of dealing with epidemics has been front and center on the stage of medical activity since antiquity! We therefore should keep unpacking the reasons why in the light of present circumstances we find ourselves willing to learn from this historical playbook. While the component 彳has been abbreviated in both instances where the character 役 (yi) for war is included in the pictograms for medicine (yi) and epidemic disease (yi), and while modern reasons for high population density have changed, many relevant things remain for us to contemplate here.9

Lihong’s insights are valuable for understanding the complex dynamics of epidemic disease. For one, we can see that epidemics are not novel occurrences, but have occupied medical thought for thousands of years. In addition, Lihong highlights the interdependent nature of epidemics, war, and medicine. Reflecting on the impact of epidemics in the late Eastern Han dynasty, Lihong notes:

The waning years of the Eastern Han dynasty were the setting for repeated natural disasters and epidemics. Of the ten epidemic outbreaks recorded in the chapter “Record of the Five Phase Elements” (Wuxing zhi) in The Record of the Later Han (Hou Hanshu), most of them occurred after the year 119 CE and fall into Xu Shen’s lifetime. The duration and human death toll of the epidemic events that occurred during the Jian’an period (196-219) were especially severe. Chancellor Cao Cao (c.155-220) described the gravity of this situation in his prose poem “Passing the Dead” (Haoli xing): “The armor of marauding soldiers remains in place, unwashed and growing nits, while people lie dead by the tens of thousands. Skeletons litter the landscape, and no cock crows for a thousand miles. Only one in a hundred still lives—just thinking of this scene breaks my heart!” Although these lines describe the misery of warfare, the end result is no different than that caused by an epidemic.10

Peter Perdue, a professor of history at Yale University, penned an interesting article at the outset of the pandemic that also notes the resonance between pandemics and war. Perdue writes:

Empires are big and microbes small, but both have shaped history by conquering territories and bodies, leaving death, disease, and devastation in their wake. Yet humans have survived many such onslaughts and brought, at hard-won cost, peace, knowledge, and protection . . . Pandemics, like wars, are ruthless auditors that test the resilience of national and international orders. Some regimes use them for domination; others find in them an opportunity for collaboration.11

What exactly is the connection between epidemic disease and war? On a physical level, warfare clearly promotes the spread of epidemic disease, where invasions cross borders and infect diverse populations. In terms of consequence, epidemics and war both devastate the populations they affect. Epidemics and war share the vector of rebellion and confrontation, combat and death—invasive influences that foster the fight for survival. Yet, epidemics and war are, in some sense, un-natural. That is to say, they are born of conditions that are disharmonious (or unrighteous) in nature, a topic discussed at length in the Tibetan medical tantras.

IV. Etiologies of Epidemic Disease in Tibetan Medicine

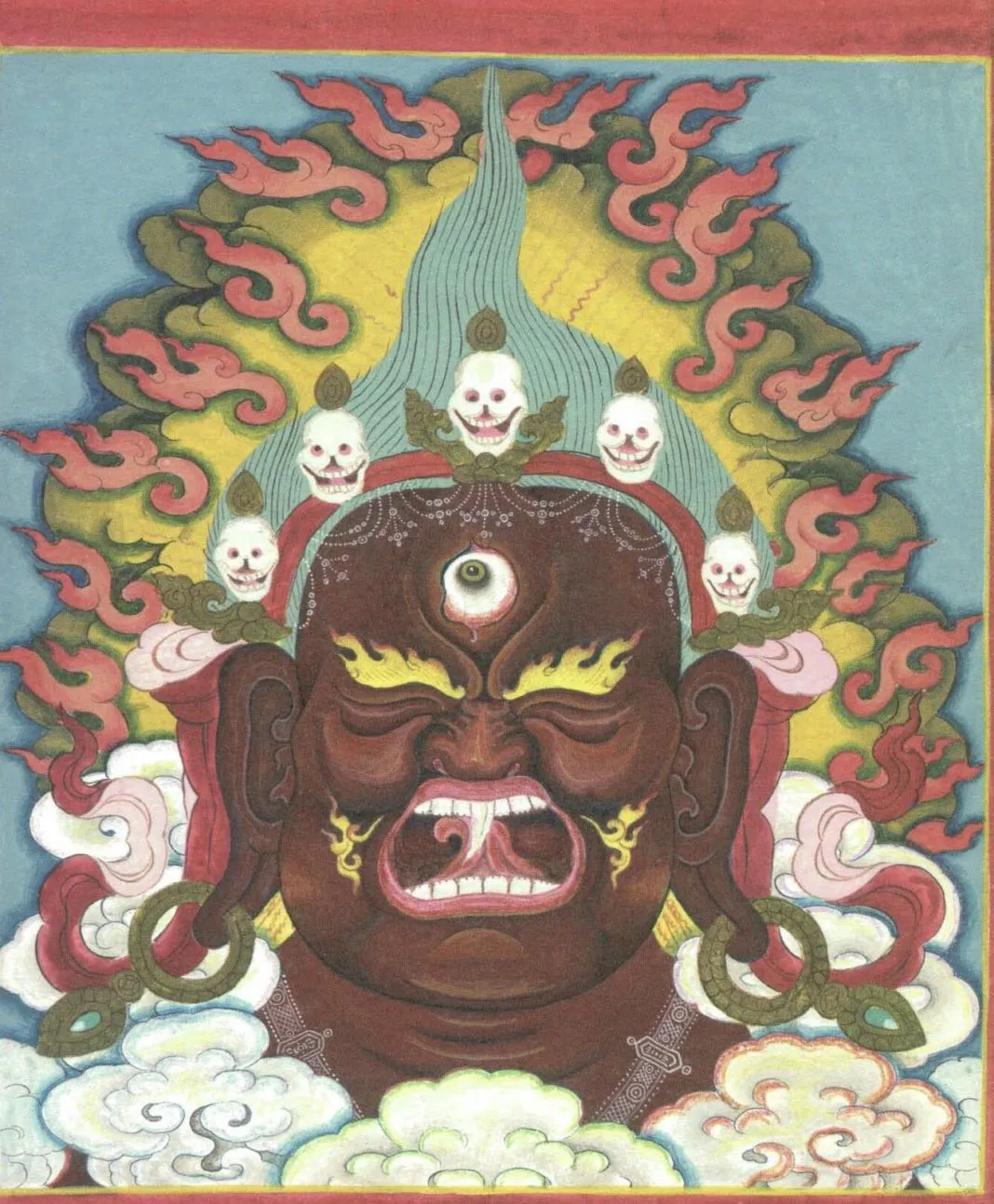

Tibetan medical tantras describe the etiology of epidemic disease in prophetic terms as a decline in righteousness that marks a degenerative age. The following passage in the Tibetan medical tantras details the cause of epidemic diseases:

The causes and conditions that originated the disease called rim [infectious disease] occurred at the beginning of the final cycle of the ten five-hundred year cycles, whereby the desires of humankind led to much transgressive behavior; rampant murders of one’s own vajra siblings spread amongst ngakpa communities; monastics engaged in bitter quarrels within their sangha; extremists committing harm to others; and groups taking vows to war and slaughter many. At that time, the mamos and [wrathful and deceptive] dakinis were enraged and the breath of disease manifested immense variegated clouds and gave rise to epidemic infectious disease, dysenteric conditions, pulmonary infections, contagious ulcerative illnesses, smallpox and other pustule-forming diseases.12

This striking passage from the tantras describes a polarized world at conflict with itself, where even spiritual brethren fight among themselves. Spiritual practitioners and monastics are considered the keepers and exemplars of peace in the world. Yet, the passage states that they are committing “rampant murders” of their “own vajra siblings” and that monastics are “engaged in bitter quarrels”. Further, we see the description of an environment full of extremism and war. The passage states that these dark conditions enrage the wrathful dakinis who then exhale the vapor of infectious disease—a poetic and ecological metaphor for the airborne transmission of contagious pathogens via spiritual provocation.

In the Tibetan worldview, the integrity of the natural world is animated by various unseen beings—nature spirits who function as guardians and protectors of the ecological landscape.13 On the surface, such descriptions may seem magical, mythical, and demonological. However, whether we choose to believe in a world literally imbued with subtle spirits or not, the fundamental message is the same: human-caused disruption of the balance of the natural world results in the formation of infection disease, a pathology provoked as a self-correcting response from nature itself. the passage is saying that the ignorant and dark actions of human beings have disrupted the balance of the natural world, resulting in the formation of infectious disease.

In another passage on epidemic etiology, the Tibetan medical tantras identify chemicals and biological warfare as causes of epidemic outbreaks:

The mamo and wrathful dakinis strike down with epidemics of vicious disease. Ill-intended extremists create compounded chemicals and substances. At this time, it is critical to protect oneself and others.14

Modern epidemiology agrees with this understanding, identifying exposure to chemicals and radioactive materials as a cause of epidemic outbreaks.15 This passage gives credence to the possibility of a “lab leak” theory on the origins of COVID-19, a theory that has gained credence in recent time. New evidence is suggestive of the animal origins of COVID-19, but there is as yet no conclusive theory on the origins of SARS-COV-2.16

During the early days of the pandemic, two Tibetan doctors (Drs. Lobgsang Dhondup and Tashi Rabten) spoke of the greed-fueled killing of animals as a root-cause of epidemics:

The root cause of these epidemics is greed. The insatiable desire to eat varieties of foods that we should not eat, to kill animals mindlessly, destroy the environment [for personal gain], and amass consumption[insatiably]. We have created severe imbalance in our world, and our ethics and compassion have deteriorated.17

Lihong discusses three etiologies of epidemics in Chinese medicine that mirror the Tibetan medical understanding: (1) the presence of a pathogen (2) unseasonal qi (3) constitutional deficiency. The first cause is well-understood in modern medicine as an infectious microbe causing the disease—in the case of COVID-19, the microbe is identified as “SARS-COV-2”. The second cause may seem obscure but is observed by us all as we note the extremes of climate change concurrent with the pandemic. The third cause, constitutional deficiency, is another way of describing susceptibility. Without susceptibility, viral microbes cannot take root in a human host and cause subsequent spread of epidemic proportions.

The Ling Shu offers an interesting perspective on susceptibility, stating a core dictum of Chinese medicine, “If righteous qi is strong on the inside pathogenic influences cannot invade from the outside”. Cultivating righteous qi, or the natural equilibrium of the body-system, is the very nature of resilience (or “immunity”). This truth is potently illustrated in the current pandemic where we see an uneven distribution of infectious possibility. One member of a household will contract COVID-19 while other members are inexplicably spared, highlighting the fact that not all persons are automatically infected upon exposure to the pathogen. The righteous movement of life-energy is maintained through proper diet and lifestyle practices, and even more importantly, by attending to our mental and spiritual health.

The following passage from the Tibetan medical tantras summarizes the causative factors of unseasonal qi and constitutional deficiency:

Other causes also comprise changes in the seasons that are in excess, deficiency or adversity to the norm; exhaustion due to excess physical exertion; contagious transmission of illness; contact with toxins and poisons; extreme rage and fear; severe mental distress; and excess attachment and greed. It also includes consumption of unsuitable or contaminated foods that cause infectious disease (rim).18

Contaminated and unsuitable foods give credence to the origins of SARS-COV-2 in the wild animal market of Wuhan. However, whether COVID-19 was caused by food or a lab leak, the root-cause remains a disturbance of the natural order caused by human behavior. In this regard, our individual and collective dietary and environmental practices deserve significant attention in the prevention of future epidemics.

Seasonal disturbances can be seen in the proliferation of natural disasters in the wake of climate change. Climatologists note that increasing global surface temperatures are leading to an increase in drought conditions and storm intensity.19 On this topic, Lihong notes:

. . . the World Meteorological Organization has reported that on February 9 of this year the record for temperatures measured on Seymour Island near the South Pole was broken by a thermal reading of 20.75 degrees Celsius (70 degrees Fahrenheit)—precisely the time when COVID-19 was spreading most rapidly throughout China. While we do not yet have enough data to understand how it all hangs together, we can say with certainty that climate change is causing the overall temperature on our planet to rise, thus contributing to the causation of “unseasonal energetics.”20

“Unseasonal qi”, or “seasons that are in excess, deficiency, or adversity to the norm”, is an easily overlooked cause of infectious disease. Seasonal disturbances indicate an imbalance at a macrocosmic level that will invariably be reflected in the microcosm—a principal reason why the health of our planet has profound consequences for the health of all who depend upon it. “Unseasonal qi” is one of the means whereby certain microbes proliferate and become pathogenic. We live in natural harmony with countless microbes that pervade the environment and reside within our bodies. In fact, these microbes are essential for our health and well-being. As the late Tibetan scholar-physician, Jampa Trinlé, summarizes:

There are 84,000 sinbu [microorganisms] that reside as coemergent in the body and, in a balanced state, provide strength and radiance to the body, enhancing longevity as well as protecting vitality and sensory organs. They facilitate the capacity for dexterity. In imbalance, they produce diseases of various types.21

Thus, the presence of microbes is not, in and of itself, the issue. However, the relative deficiency and excess of microbial activity in the body creates conditions of imbalance, an arena of health that is gaining traction in modern medicine’s understanding of the intestinal biome and the nature of the gut-brain axis. From this, we can see how unseasonal qi increases pathogenic vectors of all kinds and on all scales by disturbing the delicate balance of a diverse ecosystem—within and without.

Having explored traditional etiologies of epidemics, we will turn our attention to the treatment strategies these causative factors suggest.

V. Clinical Paradigms for Epidemic Diseases: Punitive and Unitive Measures

In modern times, the basic treatment approach to epidemic diseases has been akin to a declaration of war upon pathogenic microbes, in which the pathogen is seen as the enemy to be exterminated at all costs. Upon successful extermination, health is supposedly restored. Vaccination is one of the methodologies of this paradigm, in which ongoing immunizations are required to maintain the supposed eradication of epidemic diseases.22 Given the connections between war and epidemics, it should come as no surprise that a treatment methodology has been born from the political landscape of warfare. Yet, history has proven that fighting fire with fire has never yielded peace.

The psychological orientation at the root of this clinical approach is perhaps best expressed in an aphorism from the Brihadāranyaka Upanishad, expounded upon by Adi Da Samraj, a contemporary Spiritual Master:

In one of the Upanishads, it is said that wherever there is an “other”, fear arises. As soon as “difference” is presumed, as soon as separateness is presumed, as soon as an opponent is presumed, there is fear—or the disposition of separativeness, of self-protectiveness, of self-division. The non-presumption of an “other” is the essential principle that will liberate humankind. Wherever no “other” is presumed, Truth awakens.23

If we understand the true nature of epidemic disease, then we recognize that pathogenic microbes are not an “other”, but a disharmony in the natural system. Thus, a systems-based approach of cooperation with nature is needed, rather than engaging in a search to merely exterminate a perceived invader. This is not to imply that strong measures do not have relevance in acute situations, but it is to say that the long-term resolution of epidemic diseases requires a holistic approach and understanding.

In Not-Two Is Peace, Adi Da speaks of the self-correcting nature of systems:

Unless they are specifically prevented from doing so, all systems will spontaneously righten themselves. The universe is a self-organizing, self-correcting, and self-rightening process. All systems are self-organizing, self-correcting, and self-rightening—unless something interferes with the self-organizing, self-correcting, and self-rightening process.24

Rather than declare war on disease, we should look to restore peace within the natural order in which we inhere. Only in this way can we collectively cut the roots of epidemic disease and prevent their future recurrence. Disease is not rightfully the enemy, but a distress signal from a holistic system that needs to self-righten.

As for a clinical paradigm, Lihong calls for unitive rather than punitive measures in response to the pandemic:

If considered from the angle of unity consciousness versus the punishment of other, I have offered my thoughts on how Chinese medicine is an art that proffers unity enhancing measures (shangli) while Western medicine favors punitive strategies (shangxing) for quite some time now. The rectification of self, in this light, belongs to the way of promoting unity, while the rectification of others (i.e., the seeking of causal factors that lie outside of our self) belong to the way of retribution. Plans for the eradication of the virus, or vaccination against the virus, all belong to the way of retribution and punitive strategies, and rightfully so! A world in chaos needs to employ severe measures, indeed. However, if real peace and healing is our long-term goal, we must promote unity and apply punitive measures simultaneously, even adopt the way of unity as our main approach.25

Lihong’s perspective reminded me of a passage in the Ling Shu, where Huang Di and Qi Bo engage in an interesting dialogue on the nature of needles:

Huang Di: For me the small needles are insignificant items. Now you say that above they are united with heaven, below they are united with the earth, and in the middle they are united with mankind. To me this seems to greatly exaggerate their significance! I wish to be informed of the underlying reason.

Qi Bo: Is there anything bigger than heaven? Now, what is bigger than the needles? Only the five weapons. The five weapons are prepared to kill. They are not employed to keep [someone] alive. Furthermore now, mankind! The most precious item between heaven and earth. How could it be neglected? Now, to cure the [diseases] of humans, only the needles are to be applied. Now, when the needles are compared with the five weapons, which turns out to be less significant?26

This classical dialogue represents the transition from punitive to unitive strategies—from destructive weapons of war to instruments of healing, illustrating the role of medicine in the transformation of would-be-punitive measures into unity-enhancing modalities. The practice of medicine has been traditionally regarded as a means for restoring peace and “doing no harm”. Epidemics are an urgent sign and signal that unrighteousness is prevailing and undermining the integrity of our systems. From here, unity is the only true progress beyond the dualisms of war and peace. Yet, unity is a present-time living discovery, not only a future-minded goal. On this point, Adi Da maintains that unity has an a priori nature, a point he elaborates:

Unity cannot be achieved by combining opposites. Unity is the prior condition, the condition that is always already the case. Prior unity makes all opposites obsolete. Therefore, it is prior unity that must be enacted, rather than any continuation of the pattern of oppositions . . . The principle of prior unity applies to all human endeavor, even to the integrity of a human body or a human personality. Unity is not the result of a play of opposites. Unity is the prior condition . . . Wherever action is done in opposition to whatever force or entity is considered to be the opponent, wherever there is even a strategy relative to an opponent, the effort will fail. Some kinds of changes may be brought about—but, ultimately, everything stays the same, because the principle is one of division to begin with . . . Thus, it is oppositions that are preventing the self-organizing process from happening.27

The question is, what do unitive measures look like? A unitive measure is any treatment modality that enhances communication and balance within an existing system by cooperating with the natural laws of that system, in contrast to the extermination-approach enacted toward a perceived pathogenic enemy. Unitive measures place trust in the integrity of the system and the observation that a balanced system naturally eliminates pathology. Punitive measures, on the other hand, do not believe in any kind of systemic unity, rather human beings are viewed only as an aggregate of isolates subject to manipulation from the outside in order to be healthy. This represents an abstracting of nature into the ontological category of “thing” rather than “living process”.

In Chinese and Tibetan medical systems, treatment strategies for epidemics are largely herbal in nature. There is a treasure trove of herbal formulas for many types of contagious diseases, including epidemics, in the annals of Asian medicine. Since Asian medical systems focus on describing the nature of illnesses, all epidemic diseases can be seen in relationship to an established context of pathogenesis. This is how old traditions can still help us heal the ills of the modern day.

In addition to herbal medicine, modalities such as acupuncture, moxibustion,28 and cleansing therapies29 are employed in the treatment of epidemics, alongside dietary and lifestyle recommendations. Beyond this, Tibetan Medicine advises human beings to transcend the poisons of greed, attachment, and rage; to eat appropriate and uncontaminated foods, to avoid contact with environmental and chemical toxins, and to lead an ethical life of love and compassion for the natural world and everyone within it. Such is a truly peaceable and preventative approach to managing epidemic diseases.

Postscript January 2024: Wars in Ukraine and Gaza

Since the original writing of this essay in 2021, the world has witnessed the tragic outbreak of two wars: the Russia-Ukraine War (2022) and the Israel-Gaza War (2023). Unfortunately, these events represent a return to archaic ideologies of tribalism, nationalism, racism, and even genocide.

Communicable diseases have been an existing concern in pre-war Ukraine, a concern that is only growing since the Russian invasion of February 2022. Ukraine is currently regarded by some as being in “epidemic danger”, with the potential of spread across borders being quite high.30 The situation in Gaza is developing in a similar fashion.

The World Health Organization has warned that more will die from illness in Gaza than the war itself. This is a somewhat surprising statement, given the scores of people who have already died from Israel’s brutal warfare. War has destroyed the healthcare infrastructure in Gaza and shelters with overcrowding are increasing the likelihood of an epidemic emergence.31

These events represent a regression in human evolution and culture, a devolution that will cause history to repeat itself, as the adage goes. At the risk of sounding morbid, it seems we are on a fast track to seeing more epidemics and pandemics as time goes on. However, on a hopeful note, the possibility for change and regeneration is ever-present—it remains to be chosen.

Diamond J. The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race. Discover Magazine. Published May 1, 1999. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-worst-mistake-in-the-history-of-the-human-race

The negative consequences of agriculture do not mean that agriculture (as a whole) need be condemned. Regenerative agricultural practices promote sustainability, dietary diversity, organic crop production, and healthy soil production while allowing human beings to realize their role as stewards of the Earth. For more on regenerative agriculture, see Rudolf Steiner’s publication Agriculture.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

History. Pandemics That Changed History. History. https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/pandemics-timeline. Published February 27, 2019.

On May 11, 2023 the U.S. Government declared an end to COVID-19 as a public health emergency. Currently, researchers consider COVID-19 to be in the transitional phase from pandemic to endemic. A pandemic becomes endemic when the number of infections cease to rise exponentially.

Don’t Just Fixate on the Virus: Thoughts from Quarantine in Guilin. The Healing Order. Accessed March 2, 2021. https://www.thehealingorder.com/blog/dont-fixate-virus-thoughts-quarantine-guilin

Ibid.

Ibid.

Perdue PC. Empire’s Little Helper. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/04/smallpox-plague-china-medical-empire-artifact/

Tidwell T, Gyamtso K. Tibetan Medical Paradigms for the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Asian Medicine. 2021;16(1):89. https://www.academia.edu/76960028/Tibetan_Medical_Paradigms_for_the_SARS_CoV_2_Pandemic?email_work_card=title

For a deeper dive on Tibetan narratives of contagion, see Barbara Gerke’s “Pandemic Narratives” project: https://ari.nus.edu.sg/20331-116/

Ibid.

Epidemic, Endemic, Pandemic: What are the Differences? Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Published February 19, 2021. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/epidemic-endemic-pandemic-what-are-differences#:~:text=The%20WHO%20defines%20pandemics%2C%20epidemics

Blo bzang don grub and Bkra shis rab brtan 2020. The original article is in Tibetan; translation by Tawni Tidwell.

Tidwell T, Gyamtso K. Tibetan Medical Paradigms for the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Asian Medicine. 2021;16(1):89. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.academia.edu/76960028/Tibetan_Medical_Paradigms_for_the_SARS_CoV_2_Pandemic?email_work_card=title

USGS. How can climate change affect natural disasters? | U.S. Geological Survey. www.usgs.gov. Published 2022. https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-can-climate-change-affect-natural-disasters#:~:text=With%20increasing%20global%20surface%20temperatures

Don’t Just Fixate on the Virus: Thoughts from Quarantine in Guilin. The Healing Order. https://www.thehealingorder.com/blog/dont-fixate-virus-thoughts-quarantine-guilin

Byams pa ’phrin las 2006, 955. Quoted passage translated by Tawni Tidwell in “Tibetan Medical Paradigms for the SARS-COV-2 Pandemic”.

While epidemic diseases such as measles, mumps, smallpox, and polio seem to be eradicated with vaccination in the short-term, a morphological theory of disease suggests that these diseases are only temporarily suppressed and are eventually bound to re-emerge in the form of other diseases. The issue of SARS-COV-2 variants highlights the issue: each newly-emerging variant evades existing immunity, requiring the development of new vaccines to protect against the novel variant. Viruses naturally evolve, but vaccination seems to cause viruses to evolve much more rapidly. In other words, the resolution of diseases will not be found in the method of “attack”, but in true methods of systems-based healing. See George Vithoukas’s continuum theory of disease: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20110932/#:~:text=Through%20the%20life%20of%20a,is%20either%20maltreated%20or%20neglected.

Adi Da Samraj. Not-Two Is Peace. Fourth Edition. Dawn Horse Press; 2019.

Ibid.

Don’t Just Fixate on the Virus: Thoughts from Quarantine in Guilin. The Healing Order. https://www.thehealingorder.com/blog/dont-fixate-virus-thoughts-quarantine-guilin

Unschuld PU. Huang Di Nei Jing Ling Shu : The Ancient Classic on Needle Therapy. University Of California Press; 2016.

Adi Da Samraj. Not-Two Is Peace. Fourth Edition. Dawn Horse Press; 2019.

See the impressive and ongoing work of the Moxafrica organization on the use of moxibustion in the treatment of communicable diseases: https://www.moxafrica.org/

Specifically, the regimens of pañchakarma, known in Tibetan Medicine as le nga.

Pavlo Petakh, Аleksandr Kamyshnyі, Viktoriia Tymchyk, Armitage R. Infectious diseases during the Russian-Ukrainian war – Morbidity in the Transcarpathian region as a marker of epidemic danger on the EU border. Public health in practice. 2023;6:100397-100397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2023.100397

Health workers struggle to prevent an infectious disease “disaster in waiting” in Gaza. NPR. Published December 26, 2023. Accessed January 2, 2024.