The New Yorker, August 31, 1957 P. 34

PROFILE of Dr. Suzuki, the world’s leading authority on Zen Buddhism. Dr. S., who lectures at Columbia, is neither a monk nor a practicing Zen master, though, during his early years, he spent some time as a Zen monk. His position is that of a lay theologian, a scholar & commentator, writer, & lecturer who, though he by no means explores all the ramifications of the mystical doctrine he comes as close as anyone can to delineate it, though he is powerless to define it logically. Traces the history of Buddhism from its origin through Chinese Taoism and Indian & Chinese Buddhism. Dr. S. was born in Kanazawa, Japan, attended the University of Otani, where, later on he spent 20 years teaching. The 87-year-old philosopher makes his home with the Frank Okamura family, on W. 94th St.

On Friday afternoons, in a lecture room in the northwest corner of Philosophy Hall, at Columbia University, a small, wiry, and very aged Japanese named Dr. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki regularly unwraps a shawlful of books in various ancient Oriental languages and, as he lovingly fingers and rubs them, delivers a lecture in an all but inaudible voice to a rapt and rather unusual-looking group of graduate students. On one wall of the room is a framed photograph of the American philosopher John Dewey, who, peering over his spectacles, appears to be viewing the scene with some misgivings, as well he might. For Dr. Suzuki is the world’s leading authority on Zen Buddhism—a subject of considerable mystery to the relatively few people in this country who have heard of it at all, and a philosophy (if it can properly be called a philosophy) of extremely anti-philosophical, or at least methodically irrational, character to the even fewer people who have studied it.

Dr. Suzuki, however, does not look anywhere near as worried as Mr. Dewey. Despite his great antiquity—he is eighty-seven—he has the slim, restless figure of a man a quarter of his age. He is clean-shaven, his hair is closely clipped, and he is almost invariably dressed in the neat American sports jacket and slacks that might be worn by any Columbia undergraduate. The only thing about him that suggests philosophical grandeur is a pair of ferocious eyebrows, which project from his forehead like the eyebrows of the angry demons who guard the entrances of Buddhist temples in Japan. These striking ornaments give him an added air of authority, perhaps, but the addition is unnecessary.

Dr. Suzuki is obviously a man who thought everything out long ago and has reached a state of certainty. The certainty, it appears, is so profound that it needs no emphasis, for it is expressed in quiet, cheerful phrases (marked here and thereby the usual Japanese difficulty with the letter “1”) and punctuated by smiles and absent-minded rubbings of his forehead. Now and then, he bounces up from his desk to make his certainties even more certain by drawing diagrams on a nearby blackboard, or chalking characters in Chinese or Sanskrit. To the uninitiated, these characters, and the talk that accompanies them, are likely to be enigmatic indeed. “So, as you see,” he said at the conclusion of a recent lecture on the ancient Kegon Sutra, one of the great metaphysical documents of Mahayana Buddhism, “at this point, zero equals infinity and infinity equals zero. The result is emptiness.” With that, Dr. Suzuki carefully wrapped his books in his shawl again and took his departure, leaning gently on the arm of his secretary and constant companion, a very pretty and very young Japanese- American girl named Mihoko Oka- mura.

Dr. Suzuki’s lectures by no means explore all the ramifications of the mystical doctrine that he concerns himself with, nor do his tireless writings, which in English alone have filled a score of volumes with remarkably lucid prose. Dr. Suzuki is, in fact, merely the most celebrated and most eloquent international commentator on a branch of Buddhist thought that is followed, in a popular form, by millions of laymen in Japan (where it has more adherents than any other Buddhist sect except the Shin-shu, or Pure Land, branch of Japanese Buddhism), and, in a more advanced form, is practiced with rigorous austerity by thousands of monks and acolytes in various secluded Japanese monasteries. Moreover, Zen has recently been spreading, in a modest way, through the United States and Europe, where it has attracted the attention of artists, philosophers, and psychologists, in particular, and is enjoying the status of what some might call an intellectual fad but what many serious thinkers regard as a religious—or, at any rate, cultural—movement of considerable importance. Dr. Suzuki has himself been responsible for a good deal of this Occidental interest in Zen, and those who have given his ideas more than passing notice have included, besides the usual array of specialized scholars and addicts of the occult, a rather imposing list of well-known figures, among them Arnold Toynbee, Aldous Huxley, Martin Heidegger, C. G. Jung, and Karen Horney. American writers and musicians, ranging from J. D. Salinger to the composer John Cage and the jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, have at one time or another come under the influence of Zen, and on a different, purely religious level it has invaded both New York and Los Angeles, where small, dedicated groups of individuals are busy practicing its rites. In New York, the center of these activities is a Japanese temple that occupies the top floor of a brownstone building, known as the First Zen Institute of America, on Waverly Place. Though the First Zen Institute at present lacks an accredited Zen master to conduct its meditations (the Institute’s founder, a Japanese Zen monk named Sokei-an, died a few years ago), its disciples, about twenty-five in number, do their best to keep up the prescribed rituals of the order while awaiting the arrival of a new master, who is expected to come from Japan as soon as he learns English, and who, in the words of the Institute’s secretary, Mrs. Nicholas Farkas, has a “sufficiently irascible” personality to get the group’s discipline back into proper shape. Mrs. Farkas is not joking. The disciplines that the First Zen Institute hopes to resume are modelled on those of the Japanese Zen monasteries, and though they may strike the innocent observer as somewhat bizarre, there is no doubt about their severity.

THIS IS THE FIRST PAGE OF AN ARTICLE THAT ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE NEW YORKER MAGAZINE ON AUGUST 31, 1957. REPRODUCED BY SPECIAL PERMISSION ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 1957,1985 THE NEW YORKER MAGAZINE, INC.

DRAWING BY TOM FUNK TEXT BY WINTHROP SARGEANT

History of the First Zen Institute of America

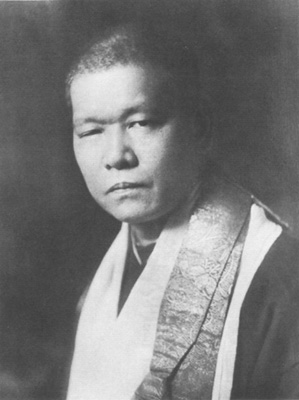

Sokei-an Sasaki, the founder of the First Zen Institute, was the first Zen master to settle permanently in America.

Sokei-an Sasaki, 1882-1945

Sokei-an’s roots as a lay practitioner trace back to the founding of the Ryomokyo-kai Zen Institute in 1875 by the Japanese Rinzai Zen master Imakita Kosen. Ryomokyo-kai was dedicated to reviving Zen in Japan by recruiting talented and univerity-educated lay people. Kosen’s most celebrated disciple, Soyen Shaku, visited America in 1893 to attend the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. In 1905 he returned to America where he lectured and taught briefly. Soyen assigned responsibility for the lay Zen institute Kosen founded to his Dharma heir, Sokatsu Shaku. This group included women and men. Sokei-an was Sokatsu’s student and came to America with him in 1906 to establish a Zen community in this country. When Sokatsu returned to Japan in 1910, Sokei-an remained to season his Zen and familiarize himself with the American character. After wandering across America and improving his English, he made several trips back to Japan and received credentials as a lay Zen master from Sokatsu. He became a priest during the 1930’s because he felt Americans would not respect a lay person bringing Zen.