Joseph Cambell and the Sacred Function of Mythology

by Adi Da Samraj

Life (from the point of view of body and mind) is the experience of “difference”, duality, opposites, conflict, and internal (subjective, or egoic) contradictions (or problems).

Religion (or sacred culture, in the broadest sense) is the Quest (via the sacred Ordeal of self-transcendence) for the Realization (or Samadhi) of non-duality (and, thus and thereby, Freedom from all “difference”, all opposites, all conflict, and all internal, subjective, or egoic, contradictions).

Mythology (like art, ritual, philosophy, and the techniques of ecstasy) is one of the primary languages of religion (or of sacred culture, in the broadest sense). And the (inherently sacred) function of mythology is to “picture” (rather than to “explain”) the Great Means, the methods (or techniques), the processes, the stages, the obstacles (or tests), the Helping encounters, the intermediary goals, and the Ultimate Goal of the religious Quest (or the sacred Way).

The inherently sacred function (and reality) of myths is obvious (and truly valued) only in the real practicing context of religious (or sacred) cultures (wherein myths are always integrated with actual practice of the religious or sacred Quest, whether in the exoteric or the esoteric manner). However, in the secular (or non-sacred, and even anti-religious) context of (especially) Western (or Occidental) culture, mythology (and even all of religious or sacred culture) is (like every other artifact and event of human experience) attached for analysis, and endless analytical (rather than truly Revelatory) explanation, by (especially) academic and scientific investigators.

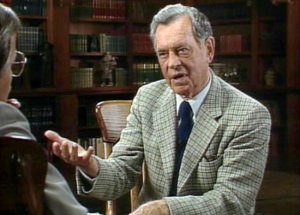

Joseph Campbell was perhaps the most popular (and thoroughly exoteric) of the recent analytical explainers of human mythologies. His method of explanation was basically academic (or intellectual), but his manner was relatively informal, generally enthusiastic, and appreciative. He could even be described as a true fan of mythology. And his academic efforts were rounded in an obvious true love of mythology. Indeed, he clearly was touched by the sacred power of mythology, such that his appreciative response to myths amounted to a kind of faith in (but not yet a Realization of) the Divine (or Absolute) Reality that eternally transcends the world.

Like the mind itself (which is always built upon, or otherwise concerned with, opposites and contradictions), Joseph Campbell’s study (or academic rehearsal) of mythology had two sides (one positive, and the other negative, or opposed to the first).

On the positive side, Joseph Campbell served to de-provincialize the minds of conventional (or exoteric) adherents of the traditional “big” (or more or less official) religions. And he also served to stimulate (or open) the relatively closed minds of secular (and, generally, anti-religious) “realists”, such that many were (like Joseph Campbell himself enabled to begin to take the sacred seriously again.

On the negative side, Joseph Campbell made the common error of the mind itself. He overestimated the significance (and the importance, or the effective depth and power) of his own thoughts. That is to say, for him, the study and appreciation of mythology was a substitute for the actual practice of religion itself (or the total discipline of the self-transcending sacred Ordeal Itself).

Mythology is one of the languages of ecstasy. And not all myths are equal. Some represent the sacred ideas and lessons associated with the earlier (or body-based) stages of life. Others represent the ideas and experiences associated with the advanced (or mind-based and higher psyche-based) stages of life. And yet others represent the Realizations associated with the Ultimate (or “Radically” self-transcending) stages of life.

Joseph Campbell was not a religious ecstatic. He was not a practitioner of the sacred Way of the esoteric (advanced and Ultimate) stages of life. He was not even a committed practitioner of the discipline of any particular exoteric religion. However, Joseph Campbell was clearly much inspired by mythology (especially, and perhaps even principally, by the exoteric and the esoteric mythology and culture of India). Indeed, he was so inspired even to the degree of a kind of faith (by means of mythological Revelation) in the Reality that always already transcends the world. And, thus inspired and faithful, he assigned to myths themselves a kind of power and verity that does not truly (or Really) belong to them (in themselves).

For Joseph Campbell, the significance (and power) of myths was in their capacity to restore the human feeling of the sacredness of human (and otherwise conditional, and body-based) experience. Therefore, his interpretations of myths (no matter what stage of life any particular myth represented) were rather consistently exoteric (and most often consistent with the humanistic, pragmatic, and generally non-mystical attitudes that are typical, and even characteristic, of the Western academic mentality).

As an illustration of this point, Joseph Campbell told of how he once met the Indian Jnani (or Advaitic Sage) known as Atmananda. He asked Atmananda (in the manner of a rather academic question, or one that he felt had already been answered by his own presumptions): If (as Indian mythology proposes) the world is an appearance in the Divine (and is, therefore, one with the Divine), must we not say “Yes” to life and to the world (and not only to the degree of embracing the world’s “good” aspects, but also to the degree of accepting, if even while struggling with, its apparently “bad”, or “evil”, aspects as well)? He claimed that Atmananda also said “Yes”, and that Atmananda was even especially responsive to this question (and, presumably, to Joseph Campbell himself), because it was, supposedly, the first question that he (Atmananda) had asked his Guru (when he and his Guru first met) years earlier.

In any case, this story illustrates Joseph Campbell’s characteristic use of mythology. For him, the affirmation (by traditional myths) of the sacredness (or even Divinity) of the world justified his own preference for the positive affirmation of human bodily existence and struggle (and this preference was not itself, or originally, based upon his study of mythology, but it was based upon his own developmental and characteristically Western cultural limitations, which bound him to the body-based point of view associated with the first three stages of life).

As I have already said, mythology is one of the languages of ecstasy. Therefore, the statements (or propositions) of mythology (and even of religious and Spiritual philosophy) are not (if properly understood) mere statements of fact (or of universal and, as mere matters of fact, always the case “truths”). Rather, they are ecstatic Revelations, or expressions of a state of Realization that (if actually Realized) presently transcends the world, the body, and much (or, in the Ultimate case, even all) of mind. Therefore, the proposition (via myths, or via ecstatic religious Teachings) that the world (including the body) inheres in the Divine (and, thus and thereby, Is Divine) is not a Call to embrace (or become further identified with, or attached to) the world (or the bodily point of view) itself. Rather, it is a Call to ecstasy, and (thus and thereby) to Divine Realization (or Samadhi) Itself, and to the Recognition (and transcendence) of all conditions in Samadhi (and, Thus, in the Realized Divine Condition Itself.).

The common error associated with each and all of the first six stages of life is the error of either separating the world (and the body, and the mind) from the Divine (or the Absolute) or of identifying the world (or the body, or the mind), in and of and as itself, with the Divine (or the Absolute). Therefore, some, like Joseph Campbell, use a mythological God-concept to justify the conventional (exoteric, body-based, and naturally egoic, or self-fulfilling, rather than self-transcending) orientation toward human existence, just as others use certain religious (and even mystical) experiences to justify their attachment to the bodily point of view (or some other form of the egoic point of view). However, the Great Statements and Myths are not expressions made from the egoic and bodily point of view (nor are they, Ultimately, even expressions that originate from mental, or psychic, experience or activity). Rather, such Great Statements and Myths are Spoken (or “Pictured”) in (or else in the recollection of) an ecstatic state (or in one or another degree of Samadhi). Therefore, such Great Statements and Myths cannot be properly understood by the ordinary (body-based) mind, nor do they Communicate a Truth that directly applies to (or intrinsically characterizes) either the world itself or the body-based mind itself.

The Great Statements and Myths can be properly “understood” only in ecstasy (or Samadhi). Therefore, they are a Call to ecstasy (or to the truly self-transcending disciplines and practices that Realize the degrees of Samadhi).

The Great Statement or Myth referred to by Joseph Campbell, that Says (or Makes a “Picture” that “Shows”) the world is arising in the Divine (or the Absolute), is not an ordinary statement of fact. From the ordinary (egoic, or self-contracted, and naturally psycho-physical) point of view, the world is entirely an experience of “difference”, duality, opposites, conflict, and internal (subjective, or egoic) contradictions (or problems). Therefore, it is not appropriate to merely affirm (or believe) any Great Statement or Myth (and, thus and thereby, to use it to justify egoic identification with and attachment to the world, the body, and the mind). Rather, any Great Statement or Myth must be integrated with a total (and necessarily religious, or sacred) culture, practice, and Ordeal of life, whereby the conditional self is transcended in (and as a necessary requirement of) the profound Quest for actual Realization of That Which transcends the world, the body, and the mind.

Even all the Great Statements and Myths Proclaim (whether implicitly or explicitly) that faith must become ecstatic (or self-transcending) practice, and practice (or ecstasy) must Realize Samadhi, for, apart from Samadhi (or direct Realization of God, or the Absolute), body, mind, and world are the incarnations of “difference”, illusion, and bondage. Therefore, faith is not an end in itself, or an excuse for the egoic life. Faith is, properly, only the beginning of the Way of faith, ecstasy, and (Ultimately, Perfect) Samadhi.

Joseph Campbell was a man of faith, but he was personally resistive to the sacred discipline of self-transcendence that is inherently a part of the religious (or sacred) culture in which myths (and especially the Great Myths, and the Great Statements) appear. He preferred (and cultivated) the “Mother-Side” of life (or the things that console and energize and seem to promise fulfillment of the world, the body, and the mind), and he resisted the “Father-Side” of life (or the influences that demand the trial of discipline, and even of responsive obedience, or sympathetic conformity). Like many other Western admirers of the East, he was not willing to accept the trial (or Ordeal) of practice, but he preferred to think, and to explain, and to indulge in the myths (and even the fantasies) of the East (and even of the totality of human sacred culture).

Indeed, Joseph Campbell, like many others (including many Westerners in the academic, scientific, and psychiatric professions), especially enjoyed (and indulged in) the glamor he inherited by mere association with the beautiful mythologies (and the Great Statements and Myths) of mankind. Therefore, even though he denied (with expected modesty) any special sense or privilege of his own sacredness (or heroism), he liberally played the role of the Western academic “guru” (spelled with a small “g”). He enjoyed. “playing” the role of a guide who points the Way to others. And he would tell his academic students (now attracted to the beauties and mind-healing powers of mythology) to “follow your own bliss” (or go and do according to your most happily felt and wanted purposes). However, Joseph Campbell was otherwise reluctant to affirm the virtue of the actual practice of the religious (or sacred) Quest itself. And he was reluctant to turn his students toward the Ordeal that goes beyond the exoteric (or ordinary human) context of the first three stages of life. And he (like so many other academic “gurus”) was reluctant (or culturally and egoically unable) to direct and release his students toward any actual Realizer (or true Guru, spelled with a capital “G”). Therefore, his influence was limited to the lesser (or more ordinary) context of human endeavor.

In the Great Tradition of mankind, teachers are sometimes called “gurus” (spelled with a small “g”). Such “gurus” are not men or women of Realization, but they instruct others in various secular and sacred arts, crafts, and sciences, in order to equip them for the ordinary human pursuit and struggle. And some of these “gurus” may also constantly remind their students of the sacred itself. Joseph Campbell was such an instructing and reminding “guru”.

However, in the Great Tradition of mankind, the sacred Ordeal Itself is the province of Teachers who are actual Realizers (of Samadhi). Of these, there are Gurus (spelled with a capital “G”) who (in the context of any or all of the fourth, fifth, and sixth stages of life) have (at one time or another) experienced Samadhi, and who, therefore, can (in the context of their own stage or degree of Realization) give first-hand Guidance (including Revelatory explanations, and, in some cases, a degree of Spiritual Transmission) relative to the techniques, processes, stages, obstacles, and goals of the self-transcending Way. And, beyond these Gurus, there are Sat-Gurus (also often referred to by the simpler reference “Guru”), or those who are presently (and constantly) in Samadhi (in the context of any or all of the fourth, fifth, and sixth stages of life, and, especially, or in the Ultimate case, in the context of the seventh stage of life), and who are unique in their Ability to fully Transmit their own (uniquely developed) Wisdom, Spiritual Power of Realization, and (in the Greatest of cases) also their own State of Realization (or Samadhi) directly to others.

Joseph Campbell was not such a Guru or Sat-Guru, but he, like many others (especially in the secular and anti-religious West, was also reluctant to Resort to such a Guru or Sat-Guru (or to recommend that anyone else, especially any Westerner, Resort to such a Guru or Sat-Guru). And this reluctance to engage or to recommend real practice of the sacred Ordeal (and in the Company of a true Realizer, of any degree) was Joseph Campbell’s limitation (as it was and is also the limitation of many other modern Western savants, including C.G. Jung, who, at least in the form of his writings, also apparently functioned, among others, as a kind of instructing and reminding “guru” for Joseph Campbell).