Lost in Translation

by Beezone

Preface

When we open Plato’s Apology, we do not hear the voice of Socrates directly. What we have before us is a text written by Plato after the fact, composed from memory, shaped by perspective, and preserved only through a long chain of transmission. The work is not a verbatim record of the trial but a dramatic reconstruction—part recollection, part philosophical portrait. Even in Plato’s day, it was already a re-telling: Socrates spoke once in the Athenian court; Plato, absent from the proceedings by his own admission, offers us a rendering that mingles what was said with what ought to have been said, all refracted through the lens of disciple and dramatist.

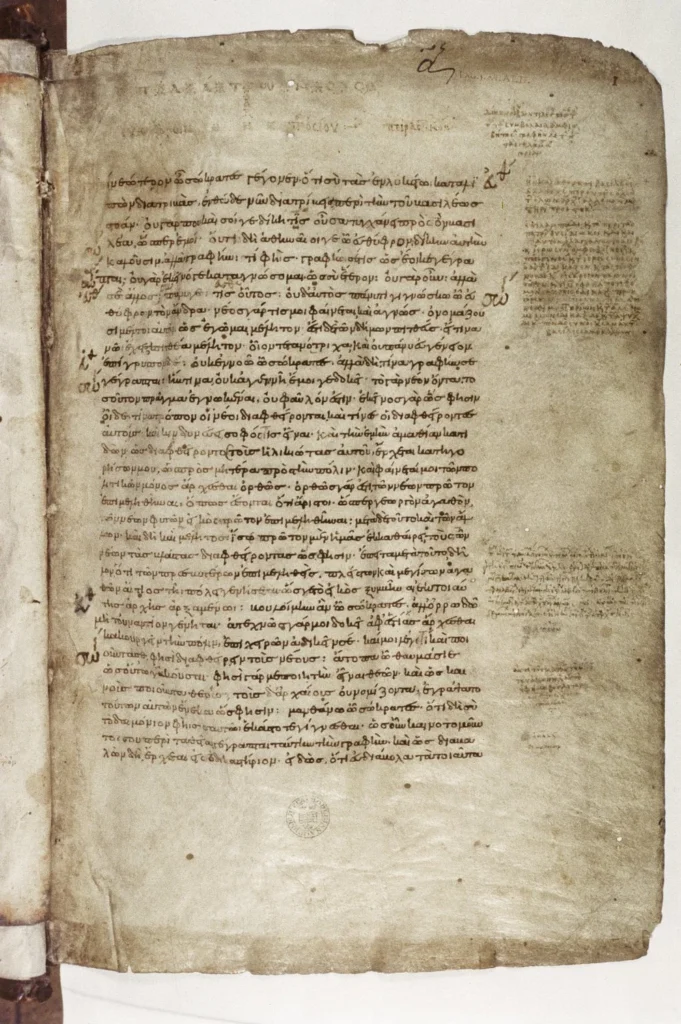

The manuscript tradition compounds this distance. What we hold in our hands today is not Plato’s autograph but a copy of a copy—centuries of scribal work intervening, each with the possibility of alteration, omission, or reinterpretation. Between Socrates’ spoken words, Plato’s remembered prose, and our printed editions lies a gulf of mediation. The voice we hear, therefore, is never simply Socrates, nor even purely Plato, but a layered text: oral performance, recollection, literary composition, and textual transmission woven together.

And then comes the translator.

Jowett’s Catalogue of Difficulties

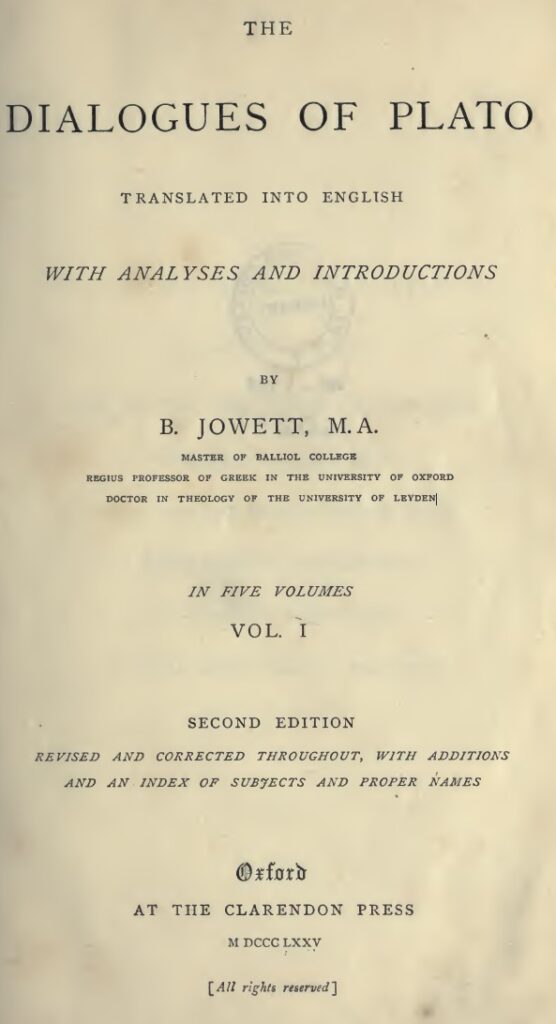

Benjamin Jowett, in his Preface to the Dialogues, laid out a sober warning: translation from Greek into English is a work of continual loss. His analysis remains as penetrating today as it was in the nineteenth century. Let us recall his main points and see how they shape our reception of Socrates’ defense speech.

-

Particles and Connectives

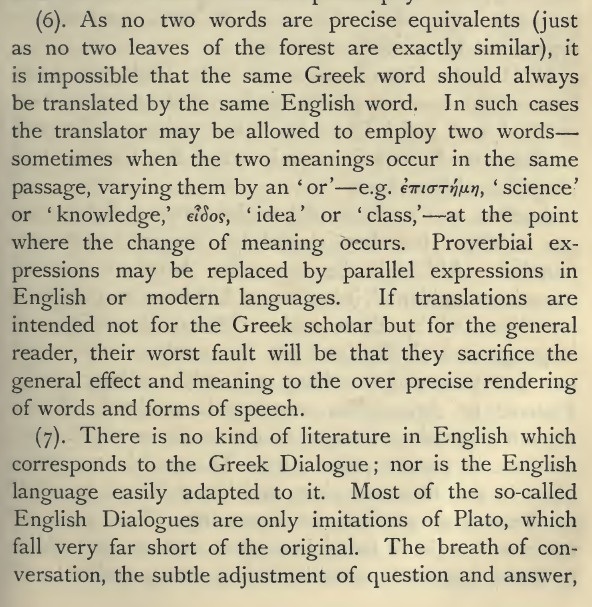

Greek thrives on a network of small connective words—δέ, γάρ, μέν, ἀλλά, τοι—that are “more words than ideas,” as Jowett says, but essential to the rhythm of thought. They oppose, qualify, infer, or soften. English cannot reproduce them without sounding pedantic or tautological. Where the Greek keeps thought in a delicate suspension, English pushes toward blunt assertion. -

Relative Clauses and Pronouns

With its flexible word order and inflected endings, Greek can sustain long chains of clauses, each carefully balanced with its antecedents. Jowett notes that English must either shorten or flatten these chains, at the cost of rhetorical suspense and nuance. -

Gender and Personification

Greek attributes genders not only to persons but to abstract qualities: the soul (ψυχή), virtue (ἀρετή), wisdom (σοφία) are feminine. In English, they become neuter “its.” What in Greek lives as a personified presence becomes in English a lifeless abstraction. -

Tautology and Repetition

Greek tolerates repetition of particles, pronouns, and even important words for emphasis. English, with its “nice sense of tautology,” abhors such redundancy. A literal translation sounds clumsy; a smoothed one loses emphasis and texture. -

Metaphor and Colour

Greek metaphors often draw from its mythic and cultural world. English translators, Jowett argues, must sometimes substitute biblical or poetic metaphors to carry equivalent force. But this substitution inevitably bends Plato’s voice toward foreign idioms. -

The Form of Dialogue

Finally, Jowett observed that there is no true equivalent in English literature to the Platonic dialogue. Most English “dialogues” are pale imitations. Plato’s works are dramas as well as arguments: the play of character, irony, and conversation is as vital as the logical content. English, with its slower conversational idiom, struggles to capture this liveliness.

Socrates Under These Limitations

If we hold Jowett’s concerns in mind, we can see how the Apology—a work already mediated by Plato’s memory and perspective—is further reshaped by translation.

The Force of Particles

When Socrates refutes an opponent or turns a phrase with “μέν … δέ,” the effect is not only logical but rhetorical, a fencing of words. English renders this as “on the one hand … on the other,” or drops it altogether. The result is that Socrates’ nimble play of opposition and inference, so natural in Greek, feels more didactic in English.

The Weight of Pronouns

As noted earlier, in Greek Socrates can spin out relative chains that mirror his very method of cross-examination. For instance:

ὃν ἂν τύχω ἀπαντήσας, τούτῳ … ἐλέγχω —

“Whomever I meet, to this one … I refute.”

The structure tightens like a net. In English, “Whenever I meet someone … I test him” is clear but flat. The method enacted in the grammar disappears.

The Neutering of the Soul

In the Apology and elsewhere, Socrates speaks of the soul (ψυχή) and its care. In Greek, the soul is feminine; in English it is neuter. Jowett saw the problem clearly: how can one attribute intelligence, nobility, or beauty to what is grammatically “it”? In translation, Socrates’ urgent appeal to care for the soul risks sounding abstract, where in Greek it resonates as care for a living presence.

The Problem of Repetition

Greek’s tolerance for repeating a word or particle allows Socrates to hammer a point home without awkwardness. In English, translators often substitute synonyms or prune repetitions, sacrificing the original rhythm. Thus, Socrates’ relentless questioning style—partly a matter of repeated turns of phrase—is dulled.

Metaphor and Register

Socrates’ invocation of his daimonion illustrates another of Jowett’s concerns. The Greek word (δαιμόνιον) is deliberately vague: “something daimon-like,” a being between human and divine. Translators render it “divine sign” or “spiritual voice.” Each choice forces an interpretation—mystical, religious, psychological—where the Greek leaves it suspended. Ambiguity gives way to clarity, and with it a loss of Socratic irony.

Dialogue as Drama

Above all, Jowett’s observation that Plato’s dialogues are dramas, not treatises, applies powerfully to the Apology. Socrates’ trial is not simply a sequence of arguments; it is a performance before an audience, blending irony, banter, indignation, and prophecy. English translation often shifts this into the register of solemn philosophy or moral exhortation. The performance is muted; the martyrdom takes center stage.

The Final Prophecy as Case Study

Consider again Socrates’ prophecy after his conviction (39c–40c).

Greek: νῦν δὲ ὑμῖν … ἐθέλω ἀποχρησμῳδῆσαι — “Now I wish to sing you an oracle.”

Jowett: “Now it is time that I prophesy to you who have condemned me.”

Here nearly all of Jowett’s difficulties converge:

-

Particles: the connective δὲ (“now, but, yet”) sets the tone, lost in English.

-

Metaphor: “sing an oracle” becomes the biblical “prophesy.”

-

Ambiguity: the dying man as ironic seer collapses into solemn prophet.

-

Dialogue as Drama: the playful performance turns into moral pronouncement.

What in Greek was a strange mix of irony and oracular chant becomes, in English, almost a sermon.

What We Lose

By tracing Jowett’s concerns through Socrates’ defense, the losses become clear. Translation alters not merely the words but the figure of Socrates himself.

-

The gadfly becomes the teacher.

-

The ironist becomes the martyr.

-

The play of conversation becomes the clarity of doctrine.

The result is a Socrates who sounds more like a modern philosopher or even a proto-Christian moralist than the elusive, playful, dramatic figure of Plato’s Greek.

Conclusion

The Apology reaches us through multiple veils: Plato’s memory, the manuscript tradition, and the limits of translation. Jowett saw the problem clearly: modern languages, while more precise and perspicuous, lack the expressive flexibility of Greek. They cannot match its particles, its personifications, its tolerance for ambiguity.

What is lost in translation, then, is not just verbal nuance but the texture of philosophy itself. Socrates’ defense was not a set of doctrines but a performance of irony, ambiguity, and dramatic presence. In translation, much of this slips away, leaving us with a Socrates easier to revere but harder to recognize.

And yet, paradoxically, this very loss is also an invitation. It calls us to read attentively, to listen for the play that escapes the English, and to remember that the Socrates who speaks to us is always more than the words on the page.