Introduction to Edward Jenner’s On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation (1801)

In the following posting, Beezone presents a rare historical document: the original 1801 article On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation by Edward Jenner, alongside a clear modern English translation for contemporary readers.

Edward Jenner (1749–1823), a country doctor in Gloucestershire, England, is widely regarded as the father of immunology. His revolutionary insight—that cowpox could protect against smallpox—led to the development of the first successful vaccine. At the time, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases in the world, claiming millions of lives. Jenner’s method, based on careful observation and experimentation rather than theoretical speculation, laid the groundwork for the modern science of vaccination and has saved countless lives.

This article, written by Jenner himself, not only documents the intellectual and empirical journey that led to his discovery, but also reflects his humility, persistence, and scientific clarity. It offers a glimpse into a turning point in medical history—when human suffering began to be pushed back by a practice that would later become a cornerstone of public health.

We offer both the original 19th-century text and a modern translation to make Jenner’s voice accessible to a wider audience. His words remain as relevant today as they were over 200 years ago.

Modern Translation:

On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation

The most important discoveries, once they become familiar to the public, are often met with indifference. Who today is amazed by the discovery of America or the circulation of the blood? Yet there is a period between the conception of a discovery and its full development—a period full of struggle, more difficult than anything men or women typically endure. There is no time more revealing of the human mind than this anxious, creative phase.

Therefore, when someone responsible for a major and useful invention describes the course of their thoughts and efforts leading to its completion, we read their story with great interest. Based on this idea, we believe our readers will enjoy the following narrative:

“I have decided to provide this brief history of the origin of vaccine inoculation because I have often noticed that people who only think about the subject casually tend to confuse cowpox—a natural disease—with the disease produced intentionally through inoculation.”

— Edward Jenner, Bond Street, May 6, 1801.

My investigation into cowpox began over 25 years ago. I became interested in this peculiar disease after noticing that, among the rural people I was often called upon to vaccinate, many who had already had cowpox were immune to smallpox. These individuals had previously experienced an illness they referred to as ‘cowpox,’ which they caught from milking cows that had a particular kind of sore on their udders. Upon further inquiry, it became clear that…

This cowpox condition had been known in dairy farms for as long as anyone could remember, and there was a vague belief that it might prevent smallpox. I discovered, however, that this belief was relatively new among them. Older farmers told me they had never heard of such an idea in their early days. This made sense to me, since the common people were rarely vaccinated for smallpox until the Sutton family introduced a more accessible method. As a result, dairy workers were seldom exposed to situations that would test whether cowpox really prevented smallpox.

“During my investigation of this subject—which, like many complex matters, presented numerous difficulties—I discovered that some people who appeared to have had cowpox still experienced the full effects of smallpox after inoculation. It was as if they had never had cowpox at all.

This led me to consult with local medical practitioners, all of whom agreed that cowpox could not be relied upon as a guaranteed protection against smallpox. For a time, this discouraged me. But I didn’t give up.

As I continued, I found satisfaction in learning that cows could develop a variety of spontaneous skin eruptions on their udders. These eruptions could be transferred to the hands of milkers. And any such matter, once passed from the cow to a human, was generally referred to as ‘cowpox’—even though it might not be the same disease in every case.”

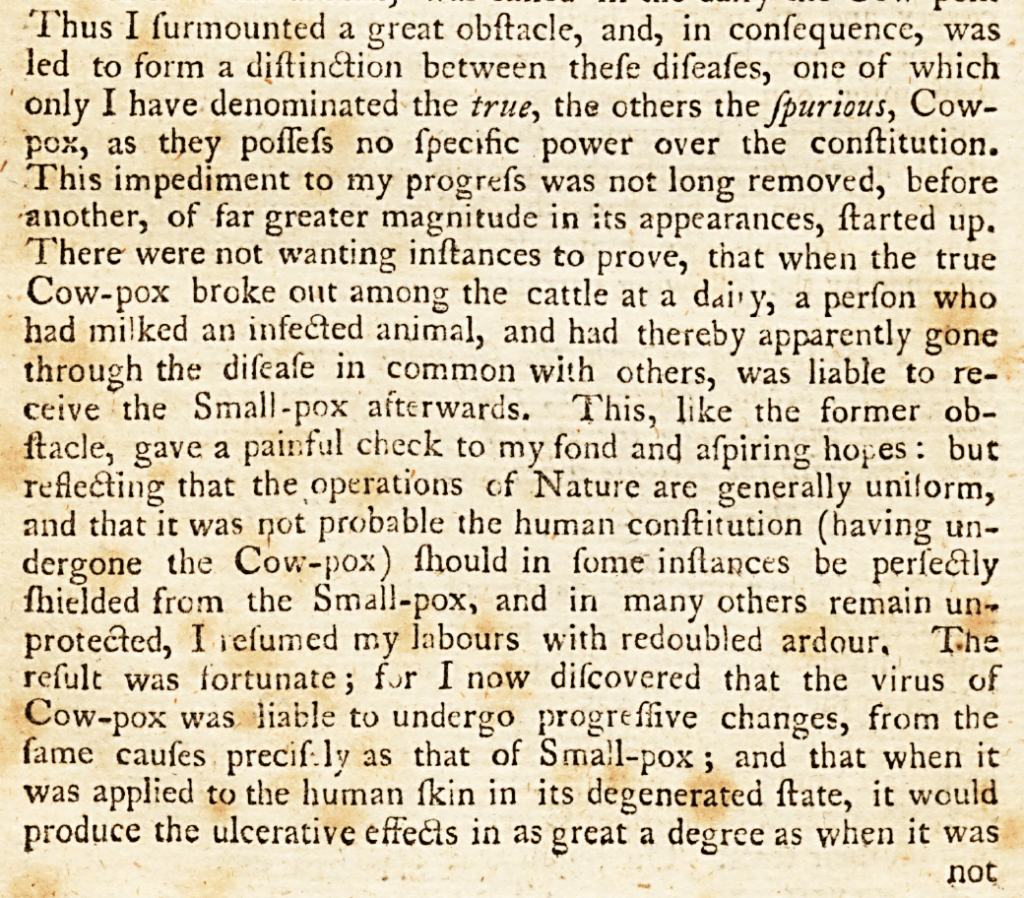

So I overcame a major obstacle, and as a result, I began to distinguish between different diseases that were being called “cowpox.” I labeled one of them the true cowpox, and the others spurious cowpox—because the latter had no real effect on the human immune system.

But just as I moved past that hurdle, an even more serious problem appeared. There were cases where true cowpox broke out among cows at a dairy, and a person who had milked one of the infected cows—having apparently gone through the disease—was still able to catch smallpox afterward.

This was deeply discouraging to my hopes. However, I reflected that the processes of nature tend to follow consistent laws. It seemed unlikely that the human body could, in some cases, gain complete protection from smallpox after cowpox, and in others, no protection at all.

So I resumed my work with renewed determination.

Eventually, I made a key discovery: the cowpox virus can go through changes—just like the smallpox virus does. When the virus was passed to humans in a weakened or altered state, it could cause ulcers on the skin as severe as those caused by smallpox when the latter is applied intentionally to the skin (through inoculation).

Sometimes the virus, though not broken down, produced even worse symptoms. But once it lost its specific properties, it could no longer trigger the necessary change in the human body that would make someone immune to smallpox.

So it became clear that one person could milk a cow one day, catch the disease, and be immune for life. But another person could milk the same cow the next day, and instead of becoming immune, they might develop sores and feel quite ill—yet their body would not gain any lasting protection. This happened because the virus had lost its special quality, and the body no longer reacted in a way that would produce immunity.

“This is where the close similarity between the smallpox virus and the cowpox virus becomes very clear. If you take the virus from a fresh pustule and use it immediately, it will produce full smallpox symptoms in the person inoculated. But if the virus is taken at a much later stage, or if it’s exposed too early to external influences that cause it to break down (in line with the natural laws of decay), then it can no longer be trusted to work.

This insight helps explain the many errors made by those who inoculated others with cowpox. They assumed the process was so simple that no mistakes were possible. As a result, they overlooked the condition of the vaccine virus. Even when the pustule had started to scab and break down, they would still use it, unaware that this could cause it to lose its effect and even create harmful outcomes.”

“While studying casual cowpox, I had the idea that it might be possible to spread the disease deliberately—through inoculation—just as we did with smallpox. The process would begin with material taken from a cow and eventually pass from one person to another.

I waited eagerly for the chance to test this theory.

Eventually, the opportunity came. The first experiment was conducted on a boy named Phipps. I inserted a small amount of cowpox virus into his arm. The virus had come from the hand of a young woman who had accidentally contracted cowpox from a cow.

Even though the sore that developed on the boy’s arm looked very similar to one caused by smallpox inoculation, the illness that followed was so mild I could hardly tell if it had worked. I wasn’t sure he was actually protected from smallpox.

But when I later exposed him to smallpox several months afterward, he remained completely healthy. This result gave me confidence. And as soon as I was able to obtain more virus from a cow, I began planning further experiments.”

40 Years Later

Sheffield and Rotherham Independent

Sat, Nov 07, 1840 Page 1

Gazette and Mercury

Greenfield, Massachusetts

January 14, 1840

“Jenner shall be more fully appreciated”