The holiday of Thanksgiving, as practiced in early American history, reflects a convergence of cultural, religious, and agricultural traditions that the colonists brought from Europe and adapted to their new environment. Drawing from Daniel Dorchester’s 1887 Christianity in the United States, we see Thanksgiving’s origins intertwined with practices of gratitude and solemn reflection rooted in both the Old and New Worlds.

Thanksgiving’s Roots in Jewish and European Traditions

The concept of setting aside time for communal gratitude, often tied to the harvest, has ancient precedents. Among the Jews, the Feast of Tabernacles, or Sukkot, (“the fruit of splendid trees, palm branches, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook.”) was a time to celebrate the gathering of crops and reflect on divine provision. This idea resonated with Christian Europeans, who observed national days of thanksgiving for military victories, as in the cases cited under Edward III, the Black Prince, and Henry V in England. These precedents framed thanksgiving as both a religious and civic practice, emphasizing collective gratitude and divine favor.

Thanksgiving in Early Colonial America

When the Puritans brought this custom to America, they adapted it to the challenges and milestones of colonial life. The first Thanksgiving at Plymouth on December 11, 1621, was held in gratitude for a good harvest following a harsh winter and significant losses among the settlers. This feast included both colonists and members of the Wampanoag tribe, reflecting an early moment of intercultural collaboration and gratitude.

In 1630, a thanksgiving was declared to celebrate the safe arrival of John Winthrop and his party in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, underscoring the practice’s flexibility in marking collective milestones beyond agricultural successes. By the following year, another thanksgiving was held for the arrival of provisions, revealing the colonists’ dependence on the uncertain flow of supplies from England and the providential view that success was owed to divine intervention.

Transition to a Regular Yearly Observance

Initially, Thanksgiving had no fixed date, as it was declared by colonial authorities in response to specific events. Civil authorities would ordain the celebration, but religious leaders often drove its significance, framing it as a time for communal worship, reflection, and gratitude to God. Over time, the festival became institutionalized in New England, transitioning into an annual observance tied to the harvest season.

Outside of New England, Thanksgiving remained largely unknown until much later, reflecting the regional distinctiveness of its early practice. This regional isolation also underscored the Puritans’ unique influence on the holiday, as their religious worldview placed a strong emphasis on recognizing God’s hand in everyday life, particularly in moments of survival and prosperity.

Fast Days and Solemn Reflection

Complementing thanksgivings were fast days, which were also widely observed by the colonists. These days were initially declared in response to communal crises, such as droughts, plagues, or wars, and later became an annual event. Fast days provided an opportunity for penitence and prayer, serving as a counterbalance to the celebratory nature of thanksgiving. Both practices reinforced a worldview that interpreted events as reflections of divine will, whether for blessing or chastisement.

Broader Context and Legacy

The evolution of Thanksgiving in early America illustrates the blending of religious and civic traditions, shaped by the challenges of colonial life. These early thanksgivings were deeply spiritual, marked by communal worship and gratitude, and often took on a communal spirit that emphasized cooperation and survival.

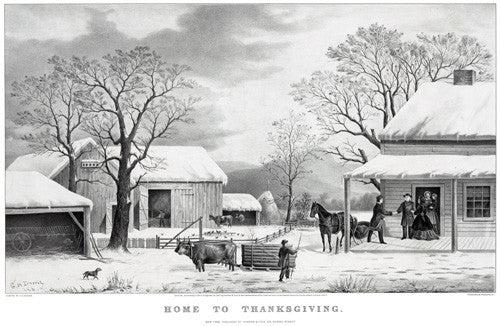

In contrast to today’s secular and national observance, early Thanksgivings were more explicitly religious and localized. The practice’s eventual spread beyond New England in the late 18th and early 19th centuries marked its transformation into a broader American tradition, culminating in Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation of a national Thanksgiving Day in 1863 during the Civil War.

Thanksgiving’s early history underscores its origins as a response to both celebration and survival, deeply rooted in the communal and spiritual life of the colonies, with influences that span cultures, continents, and centuries.