Note to the Reader

What follows is not a doctrine or a literal account, but a poetic and paradoxical meditation on the mystery of existence itself. It belongs more to the realm of wonder than of explanation. Those with a philosophical bent may appreciate its subtle paradoxes; those attuned to poetry may feel its resonance beyond words. In either case, this hymn is a profound and beautiful glimpse into how ancient minds approached the question of origins—not with certainty, but with reverence, awe, and the deepest humility. – Beezone

***

“O ye…, assemble, speak together, let your minds be of one accord, partaking like gods of old in harmony, share in the bestowed treasures…”

Rg Veda, 10.191 as cited in Rajendra P. Pandeya, “The Vision of the Vedic Seer ‘

The Nasadiya Sukta, or Hymn of Creation, from the Rigveda, explores the origin of the universe through poetic and philosophical inquiry. It doesn’t offer a definitive creation story like Adam and Eve.

(see others: In the beginning, Eggs and emptiness, Divine disorder, Egypt, Mesopotamia, The Bible story, China, Greece, Japan, Norse legends)

But instead delves into the mysteries of existence, questioning what was before and how everything came to be. The hymn highlights the unknowable nature of creation, even suggesting that the gods themselves might not have full knowledge of its origins.

Creation

Adapted from ‘The Vision of the Vedic Seer’ by Rajendra P. Pandeya from Hindu Spirituality – Vedas Through Vedana, edited by Krishna Sivaraman

The subject of the hymn 10.129 is Creation. The underlying sense of the Rig Veda hymn seems to be that absolute transcendence must transform itself into a pure immanence so that creation may emerge out of it, a point more directly expressed in a number of other hymns (e.g., RV 1.164.6 and 46; and AV 9.5). The Nasadiyasiikta section, however, makes additional points regarding creation.

In subsequent verses of the Sukta it clearly states that the One, the transcendent, is not directly involved in the creative process. In fact, while the One is—that is, simply abides as one—no creation can take place, and as a result, there are none of the oppositions that arise within creation, such as existence and nonexistence, death and immortality, earth and sky, day and night.

Creation is the process of the One’s expansion into the All, which at this stage is contained in the Void, of the primeval procreative waters (apah), “the darkness covered with darkness” of the undifferentiated chaos.

The One is “in the breathless space breathing on its own” (anid avatam svadhaya tad ekam, literally “that one breathed calmly self-sustained”.

***

Brahma, Visnu, Siva

THE DARK

In a worldless timeless lightless great emptiness

Four-faced Brahma broods.

nasad asin, no sad asit tadanim;

nasid raja no vioma paro yat.

kim avarivah? kuha? kasya sarmann?

Ambhah kim asid, gahanam gabhiram?

na mytur asid, amrtam na tarhi.

na ratria ahna asit pratekh.

anid avatam svadhaya tad ekam.

tasmad dhanyan na parah kim canasa.

tama asit tamasa gudham agre;

apraketam salilam sarvam a idam.

tuchyenabhu apihitam yad asit,

tapasas tan mahinajayataikam.

Of a sudden sea of joy surges through his heart –

The ur-god opens his eyes.

Speech from four mouths

Speeds from each quarter.

Through infinite dark,

Through limitless sky,

Like a growing sea-storm,

Like hope never sated,

His Word starts to move.

Stirred by joy his breathing quickens,

His eight eyes quiver with flame.

His fire-matted hair sweeps the horizon,

Bright as a million suns.

From the towering source of the world

In a thousand streams

Cascades the primeval blazing fountain,

Fragmenting silence,

Splitting its stone heart.

kamas tad agre sam avartatadhi

manaso retah prathamam yad asit?

sato bandhum asati nir avindan

hrdi pratisya kavayo manisa

***

Here the breathless space symbolizes the universal or comprehensive expansion into the all which is not distinct from Oneness and is therefore described as its mighty Radiance. The One’s mighty radiance, “the fulfilling energy up yonder,” gives rise to the first form from within the void of the waters (apah) which is desire (kama).

The primal desire’s arising in this manner evinces two very important factors in the creative process:

(1) the transformation of the One’s absolute transcendence into pure immanence, whereby the primal desire projects itself as psychic energy, that is, as the “first seed of mind”; and

(2) the projection of this psychic energy, which has the immediate effect of distinguishing itself from the corresponding matter (potencies) manifest within the void. Thus, with the arising of desire the ground is ready for creative activity in which psychic energy works on matter to create further forms out of it.

Clearly this hymn is concerned with the grounding of creation in the One. The grounding must be understood in a twofold manner as both immanent and transcendent. The Lord of creation is immanent, but the repose of this immanence is absolute transcendence. This state of creation would thus seem to render its secret beyond even the comprehension of the sages.

Indeed, the hymn itself says that the secret of creation is realized only in the depth of the heart (hrdi), that is, by means of exclusive devotion.

***

When the mind sees the self there is Illumination. The mind seeing the self however is not the same as the self knowing itself, for the self is not the mind, but God beyond the mind. Therefore, even after the mind has seen the self it has to be merged in the self if the self is to know itself in Truth. This is Realization. In this state the mind with its good and bad sanskaras has disappeared. It is a state beyond the mind and beyond good and evil. There is one existence characterized by infinite love, peace, bliss and knowledge. The strife between good and evil has disappeared because there is neither good nor evil, only the one undivided life of God.

Beyond good and bad

God to Man – Man to God

Meher Baba

***

Hence, the last verse of this hymn indicates the essential limitation of the capacity of comprehension on the part of both the gods and rsi(s); it need not be construed as an expression of ultimate skepticism. It describes an ontological situation which suggests that only faith brings one near the realization of the absolute transcendence and pure immanence of the One As RV 10.151 says, with faith (sraddha) alone can one attain proximity to the Divine and live forever rich and happy, even as the gods in the beginning could attain the right initiative only by reposing their faith in the fulfilling divine energy underlying the primeval waters.

It is, therefore, this faith which forms the real background of Vedic spirituality and religion; it is by it that the prayers, hymns, verbalizing of prayers, and the mind disposed to pray (idi) alike take their shape. Those oriented in this manner are called twice-born (dvija), as the sages – both gods and rsi(s) are said to be (RV 1.60.1; 6.50.2; 10.61.19). The gods and rsi(s) are for this reason kin. The notion of being “twice-born,” therefore, implies the coming to be of both gods and rsi(s) at two different levels, namely, the physical (outer, gross) and the psychic (inner, subtle). However, with the gods it is the psychic that comes first, followed by the physical, whereas with the rsi(s) the physical represents the first birth, which is then followed by the psychical. (The physical is at one further remove from spirit than the psychical and therefore more opaque or dense, in a manner of speaking, from the side of manifestation.) The gods are accordingly invoked to help man in his attempt to make the transition from a physical birth to a psychic one, for the gods are wise beings (i.e., more open to spirit) from the very beginning, that is, from the moment of their birth—as their name jatavedas, “born wise,” indicates.

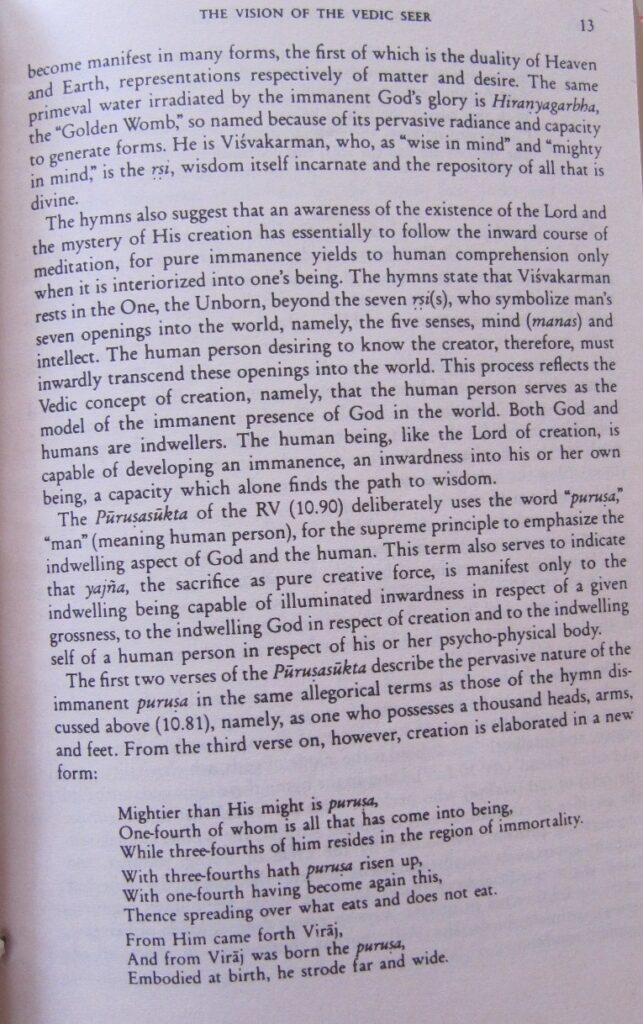

Creation hymns, such as RV 10.81 and 10.82, become manifest in many forms, the first of which is the duality of Heaven and Earth, representations respectively of matter and desire. The same primeval water irradiated by the immanent God’s glory is Hiranyagarbha, the “Golden Womb,” so named because of its pervasive radiance and capacity to generate forms. He is Visvakarman, who, as “wise in mind’ and “mighty in mind,” is the rsi, wisdom itself incarnate and the repository of all that is divine.

The hymns also suggest that an awareness of the existence of the Lord and the mystery of His creation has essentially to follow the inward course of meditation, for pure immanence yields to human comprehension only when it is interiorized into one’s being. The hymns state that Visvakarman rests in the One, the Unborn, beyond the seven ri(s), who symbolize man’s seven openings into the world, namely, the five senses, mind (manas) and intellect.

The Seven Rishis, also known as the Saptarishis, are seven highly revered sages in Hindu tradition. They are often associated with wisdom, guidance, and spiritual enlightenment. The list of the Seven Rishis can vary slightly depending on the text, but some of the most common names are Atri, Bharadvaja, Gautama Maharishi, Jamadagni, Kashyapa, Vashista, and Vishvamitra.

The human person desiring to know the creator, therefore, must inwardly transcend these openings into the world. This process reflects the Vedic concept of creation, namely, that the human person serves as the model of the immanent presence of God in the world. Both God and humans are indwellers. The human being, like the Lord of creation, is capable of developing an immanence, an inwardness into his or her own being, a capacity which alone finds the path to wisdom.

The Purusasukta of the RV (10.90) deliberately uses the word “purusa’ “man” (meaning human person), for the supreme principle to emphasize the indwelling aspect of God and the human. This term also serves to indicate that yajna, the sacrifice as pure creative force, is manifest only to the indwelling being capable of illuminated inwardness in respect of a given grossness, to the indwelling God in respect of creation and to the indwelling self of a human person in respect of his or her psycho-physical body.

The first two verses of the Purusasukta describe the pervasive nature of the immanent purusa in the same allegorical terms as those of the hymn discussed above (10.81), namely, as one who possesses a thousand heads, arms, and feet. From the third verse on, however, creation is elaborated in a new form:

Mightier than His might is purusa,

One-fourth of whom is all that has come into being,

While three-fourths of him resides in the region of immortality.

With three-fourths hath purusa risen up,

With one-fourth having become again this,

Thence spreading over what eats and does not cat.

From Him came forth Viraj,

And from Viraj was born the purusa.

Embodied at birth, he strode far and wide.

With purusa as the oblation gods performed sacrifice,

Spring was its butter, summer the woods,

And Autumn was its invocation.

With that purusa, the first of beings,

Consecrated on grass, the gods sacrificed,

The rs(s) of old and the rs(s) that followed.

(RV 10.90.3-7)

The might of purusa the indweller God is expressed in this creation, which by virtue of God’s presence abides as a self-renewing and eternal process.

But, lest one misunderstand that God thus immanent in the world process is indistinct from it, we are immediately reminded that God, the indwelling purusa, is greater than His might, in the sense that God essentially transcends the world process. Creation itself is divided into two distinct regions, the region of immortality and that of death. The region of immortality consists of three divisions: the eternal self-creating process (rta), the gods (including the Golden Womb, Hiranyagarbha), and the indwelling purusa (in the mortal frame of a human being). The region of death, on the other hand, is the eater-eaten plenum otherwise called annam (food). Now the indwelling purusa in the form of a human being is embodied in the form of eater-eaten plenum.

Adi Purusha (आदिपुरुष)

The primordial energy, now called viraj and earlier identified with the primal desire, achieves the unity between immortality and death in the form of a human person, making of him “the mortal brother of the immortal” (1.164.30,38). Viraj having come into being, having become operative, gives rise to the embodied being called “the primeval man” (Adi Purusa). Man, that is, the human person, is said to hold together death and immortality, truth and falsity (AV 10.12.14).

The yajna which is the basis of creation was discovered by the gods, the firstborn beings, to be incorporated into one’s being (AV 10.2.14). In the form of the seven sources of knowledge of illumination (the five senses, manas, and intellect): “man’s head is the abode of gods, which vitality, food and mind defend” (AV 10.2.27). Later in the hymn these same gods are called the rsi(s) of old (sadhya) who perform with the “man,” that is, the purusa, the sacrifice of creation. In this symbolic sacrifice, the whole, eternal, selfregenerating process, symbolized by the cycle of spring, summer, and autumn, enters as its ritualistic content, whereas the human, the embodied being, is the sacrificial beast (pasu). In other words, the human cognitive functions are directed in specific ways to reveal distinct kinds of beings— objects, animals, birds, the Vedic hymns themselves—in short, all of manifest nature.

The Purusasukta verses (RV 10.90.12-16) locate the points of purusa’s being from whence the manifold creation flows. Thus, the four vital points-mouth, arms, thighs, and feet-symbolize the four social functions-speech or communication, protection, procreation and preservation, and physical action. Again, four social orders-Brahmana, Rajanya, Vaisya, and Sidra-represent the external ordering of the human being. Then come the four psychic functions, symbolized by the Moon, Sun, Indra and Fire (Agni), and Wind (Vayu), namely, the mind, senses, self-luminous and appropriative intellect, and the life-force. These psychic functions, however, are revelatory of some basic cosmic functions. The first two refer to the phenomena of constant change and emergence into being, symbolized respectively by the Moon and Sun. “The Sun and the Moon move in the sea of the sky with self-generated energy, the one seeing all, and the other shaping itself ever anew” (AV 7.81.1).

The other two psychic functions represent at the cosmic level the manifestations of selfness as contrasted with everything else and the fluidity which breaks through its monadic itselfness and establishes the continuity of life between different individual selfnesses. The two relatively subtler cosmic functions are symbolized by Fire (agni, and also Indra) and Wind. The Vedas treat the natural phenomenon of fire as the symbol of selfhood in the form of Vaisvanara agni, “cosmic man-fire,” and selfhood (svaraj), which is the most distinctive feature of Indra, the king of the gods. Similarly, Wind (Vayu) is thought to represent the life-force in the form of vital breath (prana). Thus, it can be seen that the structural constitution of the human being discloses the very structure of the world.

Perhaps the human being as the model of creation is more than just an analogy. Apart from establishing the parallel of the indwelling spirit in both humanity and the universe, the analogy is clearly meant to emphasize that the human being is disclosive of the world structure and, in that sense, it is also constitutive of it. For this reason the disclosiveness that obtains in the human being is called the “sacrifice” (yajna), the path of Truth manifesting the first ordinance (dharma), following which the rsi(s) in all ages are said to attain the highest wisdom and immortality.