The Sorcerer’s Apprentice of Logic

Ed Reither

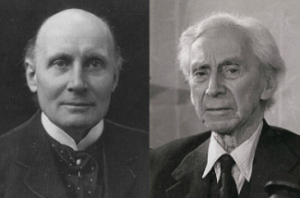

When I was at the University of New Orleans, I studied philosophy with Donald Hanks. In his courses we studied Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality. Whitehead had once been a mathematician, working with Bertrand Russell on Principia Mathematica, the great attempt to reduce all of mathematics to logic. But Whitehead eventually turned away from pure mathematics to speculative philosophy. He sensed that logic alone could not contain reality, that life was more process than structure. I could see why Russell found Wittgenstein, and why Whitehead left mathematics.

When I was at the University of New Orleans, I studied philosophy with Donald Hanks. In his courses we studied Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality. Whitehead had once been a mathematician, working with Bertrand Russell on Principia Mathematica, the great attempt to reduce all of mathematics to logic. But Whitehead eventually turned away from pure mathematics to speculative philosophy. He sensed that logic alone could not contain reality, that life was more process than structure. I could see why Russell found Wittgenstein, and why Whitehead left mathematics.

Not long after, I was teaching algebra at St. Scholastica High School in Covington. I had never studied mathematics beyond the basics, so I had to learn as I taught. A friend helped me with the simple rules — A + B = C and the distributive forms. But one thing confused me for a long time: why should X = 1? To my way of thinking, the unknown should equal zero. Unknown meant absence. Nothing. Yet algebra insisted that X could stand for 1, or any number. It took me time to see that in algebra, X was not “nothing” but a placeholder — open to be filled, not erased.

That small struggle taught me something larger. Symbols don’t carry fixed meaning. Their meaning depends on the system they belong to. In my intuitive frame, “unknown” was emptiness. In algebra, “unknown” was possibility. Same symbol, two different meanings. Later, I saw Wittgenstein’s idea of “language games” as a way of naming this. Meaning is not in the sign itself but in the use we give it.

Around the same time, I found Max Black’s The Nature of Mathematics (1933). He summarized the “logistic thesis” of Frege, Peano, Russell, and Whitehead: pure mathematics is a branch of logic. Their aim was to reduce all mathematical concepts — number, limit, derivative — to logical form. Principia Mathematica was the culmination, a massive and complex attempt to show that mathematics could be nothing more than logic. The dream was elegant, but already fragile. Gödel soon showed that no complete system could prove all truths. Even so, their work set the tone for what came after.

Today, programming and computer science carry that logic forward. Code is logic in motion. Hardware is logic mechanized, 1’s and 0’s running at light speed. Science, engineering, and much of what we call knowledge now rest on these binary systems. Logic has become the skeleton of our age.

But logic alone is structure without meaning. The systems run, but they do not know why. Meaning, purpose, and value come only from the context we provide. That is why I have come to think of this not as a line but as a spiral. Logic leads to language. Language opens to meaning. Meaning points to intuition. At the turning point, the system reaches its limit. It dissolves into itself — a kind of death — and from that death a new form is born, not as an extension but as transformation. Birth into something new.

This spiral matters now more than ever. Our machines operate at speeds far beyond human rhythm. We mold the plastic of logic into systems and then project our hopes into them. We mistake their power for wisdom. But as Goethe showed in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, power without mastery is a danger. The apprentice knows the spell but not the restraint. The broom keeps moving, the water keeps rising, and soon the house is flooded.

Whitehead warned of this in his 1925 Lowell Lectures. Science had given us more power, he said, but not more wisdom. Professionalization had sharpened technique but had not expanded direction. “We are left with no expansion of wisdom and with greater need of it.”

Whitehead warned of this in his 1925 Lowell Lectures. Science had given us more power, he said, but not more wisdom. Professionalization had sharpened technique but had not expanded direction. “We are left with no expansion of wisdom and with greater need of it.”

Bertrand Russell said the same in The Impact of Science on Society (1951). The philosophy suggested by science’s triumphs, he wrote, may itself be unwisdom, leading to disastrous results.

Which brings us to the present. What is driving all this? Why do we keep pressing forward — faster, more powerful, always searching for something better? It is not only curiosity or need. It is restlessness. A refusal to be still with what is. That restlessness has brought us medicine, technology, exploration. But it has also left us chasing knowledge as if it were an end in itself.

Knowledge without wisdom is power without guidance. And power without guidance is dangerous. If there is a task before us now, it is not to seek more knowledge but to seek the wisdom behind our quest for knowledge. Otherwise, the search itself becomes the trap. The ship moves, but appetite, not wisdom, is at the helm.

The spiral offers another way. Logic, mathematics, and machines are not wrong. They are part of the path. But they are not the whole. At their limits they dissolve, and if we let them, they can be transformed. Out of that dissolution can come something new — not more speed or power, but wisdom. Without that, we remain the apprentice, mistaking the broom for the sorcerer.

Bibliography

-

Black, Max. The Nature of Mathematics. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1933.

-

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Der Zauberlehrling [The Sorcerer’s Apprentice]. 1797.

-

Russell, Bertrand, and Alfred North Whitehead. Principia Mathematica. 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910–1913.

-

Russell, Bertrand. The Impact of Science on Society. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1951.

-

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Macmillan, 1929.

-

Whitehead, Alfred North. Science and the Modern World. Based on the Lowell Lectures of 1925. New York: Macmillan, 1925.

-

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1953.