How We Came to Call This Year 2024

Beezone, Ed Reither, and ChatGPT

magine a journey through time, beginning with the ancients who first gazed at the stars and measured the cycles of the sun. Among them were the Egyptians, brilliant innovators who crafted a calendar to keep pace with the rhythm of their lives. They noticed that the Nile’s life-giving floods coincided with the heliacal rising of the star Sirius and set their year accordingly. Twelve months of 30 days each, plus five special days, made up their 365-day calendar. It was an elegant system, though imperfect—it didn’t account for the extra quarter-day in the solar year, causing dates to slowly drift over time. Yet, this calendar became the foundation of how we understand years today.

magine a journey through time, beginning with the ancients who first gazed at the stars and measured the cycles of the sun. Among them were the Egyptians, brilliant innovators who crafted a calendar to keep pace with the rhythm of their lives. They noticed that the Nile’s life-giving floods coincided with the heliacal rising of the star Sirius and set their year accordingly. Twelve months of 30 days each, plus five special days, made up their 365-day calendar. It was an elegant system, though imperfect—it didn’t account for the extra quarter-day in the solar year, causing dates to slowly drift over time. Yet, this calendar became the foundation of how we understand years today.

Fast forward to the first century BCE, when Julius Caesar, ruler of Rome, sought to bring order to the chaos of the Roman calendar, which had fallen wildly out of sync with the seasons. In Alexandria, a city that was a beacon of learning and home to the great Egyptian astronomers, Caesar found his solution. Borrowing heavily from the Egyptian system, he introduced the Julian Calendar in 46 BCE. By adding a leap day every four years, the drift was reduced, aligning the calendar with the solar year. For centuries, this system governed the Roman Empire and later much of Europe, anchoring human lives to the natural cycles of the earth.

Marking Time by Emperors

In the early days of the Julian Calendar, years were named not by numbers but by the reigns of emperors. To say when something happened, you might declare it was “the 10th year of Emperor Augustus” or “the 3rd year of Emperor Diocletian.” This system made sense in a world where rulers symbolized the passage of time itself. Each emperor’s reign marked a chapter in history, and the continuity of their rule helped people anchor their own lives within a larger story.

Even as the Roman Empire waned, this practice endured. Early Christians, too, marked time by emperors, such as in the Gospel of Luke, which begins its account of John the Baptist by noting it was “the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar.” For centuries, the timeline of history was a tapestry woven with the names of rulers, each year an echo of their power.

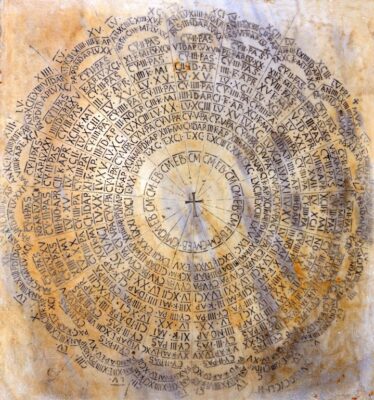

A New Way of Counting: Anno Domini

The shift from marking years by emperors to counting from a fixed point in history began with a monk named Dionysius Exiguus in 525 CE. In his effort to calculate the date of Easter, Dionysius devised a system that counted years from what he determined to be the birth of Christ, calling it Anno Domini—“the year of our Lord.” Though Dionysius’s calculation was later found to be a few years off from the actual birth of Jesus, his system introduced a new way of framing time, one rooted not in the reign of kings but in the life of a savior.

Still, the transition was slow. For centuries, the Anno Domini system coexisted with regnal years and other local methods of marking time. Yet, as Christianity spread across Europe, the practice of numbering years from the birth of Christ gained prominence. By the Middle Ages, the framework of BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domini) became the dominant way to place events on the timeline of history.

The Gregorian Revolution

The Julian Calendar, while a great improvement, was not perfect. By the 16th century, the slight miscalculation of the solar year—off by 11 minutes annually—had caused the calendar to drift by 10 days. This discrepancy was especially troubling to the Church, as it threw off the date of Easter, a cornerstone of Christian worship.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII took bold action. He introduced the Gregorian Calendar, correcting the leap year system to ensure greater precision. By omitting leap years in three out of every four century years (e.g., 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not leap years, but 2000 was), Gregory realigned the calendar with the solar year. He also advanced the calendar by 10 days, restoring the date of Easter to its intended place.

While many Catholic nations adopted the Gregorian Calendar immediately, Protestant and Orthodox countries were slower to follow. It wasn’t until centuries later that the Gregorian Calendar became the global standard. Today, it is the calendar used almost universally for civil purposes.

From Pharaohs to 2024

And so, here we are in the year 2024—a number that carries the weight of millennia. Behind this simple designation lies the story of the Egyptians and their solar wisdom, the Romans and their imperial ambitions, the Christian monks who sought to align time with the divine, and the scientists and leaders who refined our understanding of the heavens.

The year 2024 is more than a marker on the calendar; it is a testament to humanity’s enduring effort to measure and make sense of the passage of time. It connects us to the Nile’s floods, to Julius Caesar’s reforms, to the monks counting the years of Christ, and to the astronomers who perfected our clocks.

As we live through this year, may we remember the intricate web of history that brought us here and the shared human quest to anchor our lives in the vast expanse of time. After all, each year is a reminder that we are part of a story far greater than ourselves—a story written not just in numbers but in the stars, the seasons, and the enduring rhythms of the earth.