An International Congress

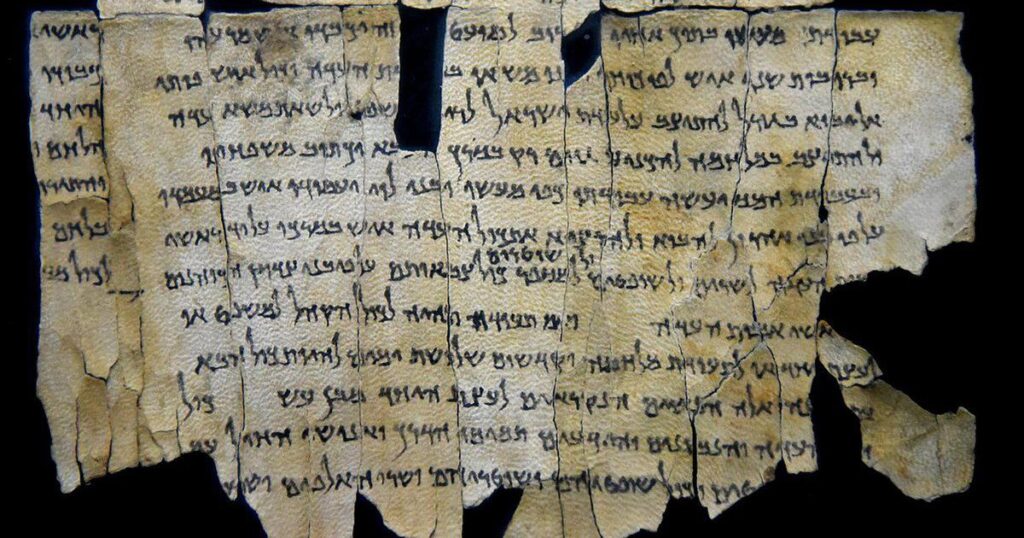

THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS

FIFTY YEARS AFTER THEIR DISCOVERY

Jerusalem, July 20-25, 1997

The closing presentation

Professor Hartmut Stegemann, Georg-August University, Gottingen outlined the challenges that awaited the scholars in the next century. He explained how research may disqualify many theories, which are presently still discussed, regarding the Qumran/Ein Feshkha settlement, the identity of its former inhabitants, or its relationship to the scrolls from the caves, and while their interpretation will be discussed well into the next century, they will surely shed light on, the Hebrew Bible, the economic and historical aspects of early and middle Temple times, and the background of the Qumran scrolls for Rabbinical Judaism and early Christianity.

***

The Dead Sea Scrolls

and the Jewish Origins of Christianity

Carsten Peter Thiede

Chapter I – What the Ancients Knew

CASE OF A STRANGE SECT AT THE DEAD SEA

Long before the caves of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the ruins of Qumran were discovered and connected with a Jewish group commonly called ‘Essenes’, it was known that a certain Jewish orthodox movement had settled near the Dead Sea, somewhere between Jericho and En Gedi. There was Pliny the Elder, the Roman statesman and natural historian who died during the eruption of Vesuvius in ad 79. He mentions the general region of their settlement and calls them ‘Essenes’. In Alexandria, there was Philo, an influential Jewish philosopher and diplomat, who died in c. ad 50. He knew at least some of their teachings – fact which seems to show the contents of the Dead Sea Scrolls were anything but secret documents for a small Jewish group of hidden desert ‘monks’. And there was Josephus, a former Pharisee and priest,

This chapter quotes, describes and analyses their statements. And it goes on to ask why these ‘Essenes’ are not mentioned in the New Testament, that other collection of contemporary Jewish, messianic documents. Or are they there, somewhere, after all?

From Pliny to Josephus

Everyone who visits the ruins of Qumran for the first time is struck by a surprising impression: the rediscovered settlement is not an isolated place of refuge in the middle of nowhere, out of reach to the ordinary traveller, surrounded by an arid desert with nothing but the Dead Sea to enliven the eye. On the contrary, it is situated on a plateau, clearly visible even from a distance on the road which links Jericho with Masada, En Gedi, Sodom and Eilat. Virtually next door, a couple of hundred yards away, there is a flourishing oasis called En Feshkha. Cattle, plants, trees and fresh water in abundance are the hallmarks of this oasis. Neither the road nor the oasis are new; they existed when those who settled at Qumran first came to this site. In fact, the habitation of this region by people who did not intend to live in excessive poverty is documented as early as the neolithicum. Qumran was not called Qumran in those days – that is a modern Arabic name given to the place when it was re-excavated near the caves as late as 1953-56, during the Jordanian occupation of the region.1 From Joshua 15:61-62, at the end of a list of the cities belonging to the tribe of Judah, we may gather that its ancient biblical name probably was Secacah: ‘And in the desert were Beth-Arabah, Middin, Secacah, Nibshan, the City of Salt and En Gedi. These are six towns with their farmsteads.’ In other words, En Feshkha would have been the ‘farmstead’ of Secacah’. And Secacah is singled out as a Dead Sea settlement in the famous Copper Scroll from Cave 3 (3Q 15). This is an inventory of priestly and community treasures clearly linked with a particular community – the one which we call Essenes – who apparently hid them from the approaching Romans before they finally occupied the area in ad 68.2

The oldest non-Jewish source is provided by Pliny the Elder. He was an uncle of that other Pliny, conveniently called the Younger. The younger Pliny was a Roman governor in Pontus and Bithynia (the area addressed in Peter’s first letter) between c. ad 111 and 113 and became famous for his published correspondence with Emperor Trajan about the legal niceties of anti-Christian trials. Uncle Gaius, the Elder, was an army commander and procurator in several provinces, and a skilled observer of nature and natural life. His Naturalis Historia or History of Nature (NH) is an invaluable collection of information about practically everything known in these fields at his time. The only detailed description of papyrus and its production which has survived from antiquity can be found in Book 13 of this compendium, and there are many similar gems. We can safely date the conclusion of this work to ad 79, for in this year, he died in an eruption of the Vesuvius volcano, during a valiant attempt to observe the effects of the eruption on the seashore, with a pillow on his head to protect him against the stones. And it was certainly written after ad 70, the year of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans, because he calls Jerusalem and En Gedi ‘heaps of rubble’. Pliny describes the Essene settlement at the Dead Sea. He says:

To the west the Essenes fEsseniJ… had settled at a distance from the harmful shores [of the Dead Sea], a group of people [gens] which was unique in the whole world, more praiseworthy than others, without any women, having abandoned all sexual love,3 without money,4 in the society of palm trees.5 Thanks to many new arrivals, they are daily reborn in equal numbers: considerable numbers of people who have been worn down by the vagaries of fortune have come and accepted their customs. Therefore, and although it may sound incredible, this eternal people, into which no one has besen born, has existed for thousands of years. So fruitful is for them the penitence which others express for their lives. Below [south of] them was the town of En Gedi [Engada] which was second only to Jerusalem in fertility and palm tree groves, but now is merely another heap of rubble.

We may wonder how much Pliny really knew about the Essenes and their rites. Those ‘thousands of years’ may be nothing more than a rhetorical exaggeration. As we shall see in the next chapter, Qumran/Secacah was inhabited at least from the eighth century bc. After an interruption, probably in the early sixth century bc, it was reinhabited by new settlers – commonly called Essenes – during the reign of John Hyrcanus (135-104 bc). The settlement may have been destroyed by an earthquake and an ensuing fire in 31 bc, or by the Parthians in c. 39 bc, or during the skirmishes between Herod the Great and the Hasmonean Antigonos (c. 37 bc). Whatever the cause may have been, we are talking about the same period, and about the fact that Qumran was destroyed. It was rebuilt, apparently by the same people who had lived there before, during the reign of Archelaus (4 bc-ad 6), a ruler also mentioned in the New Testament (Matthew 2:22). If Herod did favour the Essenes, as Josephus claims (Antiquities 15, 373-78), it is certainly noteworthy that they did not live at Qumran during his reign. It seems this period coincides with the Essene establishment of a major centre in Jerusalem, supported by Herod the Great, on the south-west hill which today is called Mount Zion. And it should not be overlooked that some of the literature which was used by the Essenes (like the Book of Jubilees which was found in Caves 1, 2, 3, 4 and 11) existed long before the movement which we may identify as the Essenes of Pliny, Philo and Josephus, split from the Sadducean temple priesthood and went into ‘exile’ as the faithful few of Israel. According to the chronology of a very central text, the so-called Damascus Document, this happened in 196 bc. Twenty years later, in 176 bc, the ‘Teacher of Righteousness’, whom we shall encounter again in this book, rose from among the group as their charismatic leader. The Damascus Document was written, it seems, not long after the Teacher’s death in c. 150 bc, during the reign of the High Priest Jonathan (160-142 bc) who may or may not have been the ‘Wicked Priest’ attacked in the scrolls. It looks as though the Teacher guided the movement before it settled in Qumran, and perhaps the decision to move to Qumran, probably from the ‘Land of Damascus’ in the Yarmuk region – closer to Jerusalem but still in the ‘wilderness’ – was inspired by his death. In any case, all we can say at this stage is this: it kind of Essenism taken on and developed by the Qumran/Jerusalem iriiiivs may have existed a considerable time prior to the rise of the movement which lived in Qumran and Jerusalem until these places uric destroyed by the Romans in ad 68 and 70 respectively. This does not give us ‘thousands of years’, but a considerable period of develop- ilieiil before Pliny set pen to paper.6

But what are we supposed to make of those masses (turba) of newcomers who flocked to the site and adopted the Essene lifestyle? Taken in its narrowest sense, Pliny’s statement is plainly wrong. The size of the settlement did not allow for more than 60-100 inhabitants. But the archaeology of the area has shown many more settlers were living nearby, on the outskirts, and particularly at the oasis of En Feshkha which was (and is) literally only a stone’s throw away, bulging by remains found at graveyards, whole families with children may have lived there, people who – in the terminology of Christian communities might be alled ‘tertiaries’. Pliny’s description could therefore be an accurate reflection of this evidence: single people and families, fed up with their previous lives, ‘escaped’ to Qumran and settled in the vicinity of the main settlement. But even so, we are not given any details. Whatever source Pliny used for his information, he did not quote from Essene literature, nor did he explain why so many people felt attracted to their lifestyle. Celibacy alone does not sound sufficiently persuasive for multitudes including men with wives and ichildren. Philo and Josephus will provide us with further information. As for the centre at the Dead Sea, there is one other early author who confirmed Pliny’s description of the site and its inhabitants. He was a man called ‘Gold-Mouth’ (Greek Chrysostomos) by his contemporaries: Dion, born in Prusa (modern Bursa), a city in the district of Bithynia which is mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1. He lived from c. 40 to c. 115 ad, opposed Emperor Domitian, was sent into exile, but was eventually rehabilitated and appreciated as an outstanding philosopher and orator by Domitian”s successors Nei va and Trajan. During his years in exile, in the 90s of the first century, Dion travelled widely throughout the empire and met other travellers whose impressions he used at leisure. Since Qumran was occupied by the Romans in ad 68, it is doubtful whether he saw the site himself when it was an Essene settlement, but it is quite possible that his knowledge was derived from first-hand information. Synesius of Cyrene, who preserved Dion’s statement in his biography of the gold-mouthed one, had this to say:

Elsewhere, he [Dion] praises the Essenes who have their own prosperous city [polin] near the Dead Sea, in the middle of Palestine, not very far from Sodom.7

We are not told what Dion praised them for. Like Pliny, he situates them near the Dead Sea. The reference to Sodom is neither here nor there; in those days, some people thought it was at the southern tip of the Dead Sea, where the modern town of S(o)dom is situated, and others located it in the north. If Dion was one of those who preferred the northern site – like Philo, for example,8 – his description would agree with that of Pliny. And like Pliny, who presupposes it indirectly, he seems to have known about the relative affluence of the Essenes. If the oasis of En Feshkha was seen as part of the Essene settlement, or, as Dion calls it, their ‘polis’, then indeed there is no reason to suppose the hallmark of life down there was poverty, attrition, hunger and thirst in a less-than-splendid isolation. A consciously frugal lifestyle may be all the more convincing if it is exercised within eyesight of fish, flesh and fowl in abundance. In any case, the fame of the Essenes must have spread to distant regions of the Roman empire – where men such as Pliny and Dion lived and wrote – to such an extent that their praiseworthiness was recorded even after they had ceased to exist.

Pliny and Dion were non-Jewish compilers. They focused on the Dead Sea. Others painted a broader canvas and emphasized that this habitation at the Dead Sea was the centre, but not the only settlement, village, town or city associated with the Essenes. This, in .my case, is presumed by two contemporary authors – and unlike Pliny and Dion, Jewish ones at that – Philo of Alexandria and Josephus. Philo, perhaps the greatest Jewish philosopher of the late Second Temple period, a diplomat who led a delegation to Emperor Gaius (Caligula) and protested against anti-Jewish events in his city (and wrote a moving essay about it), saw Judaism in Galilee, Judea and Samaria from a distance – geographically and also, to a certain extent, culturally. It seems that he, like many Jews in the diaspora, did not know Hebrew and depended entirely on the Greek translation of the Bible, the so-called Septuagint.9 He duly cut the Gordian knot of Hebrew versus Greek scripture by calling the Septuagint equally inspired by God.10 Thus, we may safely assume the only Essene writings of which he could have had first-hand knowledge were those written in Greek. And there were indeed a few, some of them rediscovered in Caves 4 and 7; those from Cave 4 may even have been known outside Qumran before the death of Philo, in c. 50 ad. Indeed Philo wrote about Essene community settlements all over the Jewish homeland:

Certain among them [the Jews in Syrian Palestine], to the number of over four thousand, are called Essaeans [EssatoiJ. Although this word is not, strictly speaking, Greek, I think it may be related to the word ‘holiness’. Indeed these men are utterly dedicated to the service of God; they do not offer animal sacrifice, judging it more fitting to render their minds truly holy. For it should be explained that, fleeing the cities because of the ungodliness customary among town-dwellers, they live in villages; for they know that, as noxious air breeds epidemics there, so does the social life afflict the soul with incurable ills. Some Essaeans work in the fields, and others practise various crafts contributing to peace; and in this way they are useful to themselves and to their neighbours. They do not hoard silver or gold, and do not acquire vast domains with the intention of drawing revenue from them, but they procure for themselves only what is necessary to life. Almost alone among mankind, they live without goods and without property; and this by preference, and not as a result of a reverse of fortune. They think themselves thus very rich, rightly considering frugality and contentment to be real superabundance.” In vain would one look among them for makers of arrows, or javelins, or swords, or helmets, or armour, or shields; in short, for makers of arms, or military machines, or any instrument of war, or even of peaceful objects which might be turned to evil purpose. They have not the smallest idea, not even a dream, of wholesale, retail, or marine commerce, rejecting everything that might excite them to cupidity.12 There are no slaves among them, not a single one, but being all free they help one another.13

Philo goes on for several more pages, but they are about the ‘philosophy’ and other aspects of Essenism, and to this we shall return later. In another writing, a kind of ‘apology’ of Judaism written for non-Jewish readers, he takes up the thread and sheds some additional light on their lifestyle. Towards the end, he offers a curious and lengthy diatribe against the dangerous and subversive flattery of women which we have preferred to omit from the following quote:

They live in a number of towns in Judea, and also in many villages and large groups. Their enlistment is not due to race (the word race is unsuitable where volunteers are concerned), but is due to zeal for the cause of virtue and an ardent love of men… There are farmers among them expert in the art of sowing and cultivation of plants, shepherds leading every sort of flock, and bee-keepers. So they have to suffer no privation of what is indispensable to essential needs, and they never defer until the morrow whatever serves to procure them blameless revenue. When each man receives his salary for these different trades, he hands it over to one person, the steward elected by them, and as soon as the steward receives his money, he immediately buys what is necessary and provides ample food, as well as whatever else is necessary to human life. Daily they share the same way of life, the same table, and even the same tastes, all of them loving frugality and hating luxury as a plague for body and soul… Shrewdly preparing themselves against the principal obstacle threatening to dissolve the bonds of communal life, they banned marriage at the same time as they ordered the practice of perfect continence. Indeed no Essaean takes a woman because women are selfish, excessively jealous, skilful in ensnaring the morals of a spouse and in seducing him by endless charms… The life of the Essaeans is indeed so enviable that not only individuals but even great kings are seized with admiration before such men, and are glad to pay homage to their honourable character by heaping favours and honours upon them.14

A slightly younger observer of the scene was Josephus. He has been described as one of the most fascinating characters of his time. Born in c. ad 37, he was a trained Pharisee and priest, went to Rome with a Jewish delegation in c. 64, secured the release of some priests who had been sent to the capital on a false charge by procurator Felix (the same Felix who held Paul captive at Caesarea), was persuaded to join the zealots who revolted against the Romans between 66 and 74, became a commander of their forces in Galilee, fought on horseback in battles near Bethsaida, was captured and was a candidate for execution when he had a brilliant idea: he predicted that his captor, t he Roman general, Vespasian, would become emperor. It was a fair chance, fifty-fifty. Without this wager, the likelihood of his survival would have been zero. To almost everyone’s surprise, Vespasian did ecome emperor in ad 69 and left his son Titus to finish the job of estroying Jerusalem and the Temple and of mopping up the Jewish isurgents. Josephus become the emperor’s adviser on Judaism, a iampered courtier who lived mainly in Rome until his death in c. ad 98. osephus, who assumed the name of the imperial family of the Flavians and was henceforth called Josephus Flavius, wrote a series of listorical and semi-autobiographical books, among them the Jewish War and the Jewish Antiquities. Both these writings contain enumerable details about Jewish life, culture, politics and religion rom ancient days to his own time. Even people from the pages of the few Testament play a role in the Antiquities: John the Baptist, laiaphas, Pontius Pilate, the Herodians, Jesus, and his brother ames.15 Josephus, it seems, knew the Essenes quite well – in any case, he claimed he had spent some time with them before he decided to join the Pharisees instead:

When I was about sixteen, I wanted to gain first-hand experience of our different movements. There are three: first the Pharisees, second the Sadducees, and third the Essenes – as I have noted frequently. 1 thought that I would be able to choose the best, by learning about all these schools. Thus I steeled myself for the task and studied the three courses with some effort.16

In spite of this personal acquaintance – and Josephus is the only contemporary author who claims to have spent time with the Essenes – his portrayal of their theology is tinted by his own position in the eligio-political power game before and during the Jewish revolt. Like ’Philo, he mentions a number of approximately 4,000 male Essenes, and says their dwelling places were to be found in the whole country.17 Such camps and quarters are mentioned in the Damascus Document,18 and a Qumran text which has only survived as a fragment,, 4Q 159 (‘Ordinances’, fragments 2 4), refers to at least one settlenient outside Qumran for which it provides legal advice. A movement called the ‘Therapeutae’, active mainly in Egypt, is also linked with the Essenes, and there were commercial and cultural links between both parts of the Roman empire.19 In fact, Essene or near-Essene groups or offshoots may have continued to exist in Egypt long alter their disappearance from the Holy Land. It may not be an accident that an early medieval copy of the archetypally Essene Damascus Document was found in the genizah, the storage room for damaged or discarded manuscripts, at the Ben Ezra synagogue of Old Cairo in 1897. There is no reason why individual Essenes should not have reached other centres of the empire, Athens and Rome among them, and why they should not have developed nuances within the hamework of Essene rules and regulations, which were reflected in different scrolls.20 But this question, tantalizing as it may be, is beyond the scope of this chapter. If the number of ‘mainland’ Essenes given by Josephus is even remotely correct, it follows that these people simply had to settle in other places outside Qumran as well; the number of houses and the size of the dining hall at Qumran did not allow for more than 60 to 100 – some scholars would say up to 150 – inhabitants at a time.21 Here is one of the relevant passages from Josephus:

The Essenes renounce pleasure as an evil, and regard continence and resistance to the passions as a virtue. They disdain marriage for themselves, but adopt the children of others at a tender age in order to instruct them; they regard them as belonging to them by kinship, and condition them to conform to their own customs. It is not that they abolish marriage, or the propagation of the species resulting from it, but that they are on their guard against the licentiousness of women and are convinced that none of them is faithful to one man. They despise riches and their communal life is admirable. In vain would one search among them for one man with a greater fortune than another. Indeed, it is a law that those who enter the sect shall surrender their property to the order, so neither the humiliation of poverty nor the pride of wealth is to be seen anywhere among them. Since their possessions are mingled, there exists for them all, as for brothers, one single property…

They are not in one town only, but in every town several of them form a colony. Also, everything they have is at the disposal of members of the group arriving from elsewhere as though it were their own, and they enter into the house of people whom they have never seen before as though they were intimate friends. For this reason also, they carry nothing with them when they travel: they are, however, armed against brigands. In every town a quaestor of the order, specially responsible for guests, is appointed steward of clothing and other necessaries.22

These four then, Pliny the Elder, Dion of Prusa, Philo and Josephus are informants who lived while the Essenes were flourishing and whose writings are based on contemporary information. This remains true in spite of the fact that with one exception (Philo), they all wrote after the destruction of Qumran and the dispersion of the Essenes in ad 68. Even without the complexities of Essene discipline, theology and Messianism, it seems we already have a miniature painting with a few basic colours:

the Essenes had their headquarters near the Dead Sea, south of Jericho and north of En Gedi;

*they possessed a second centre in Jerusalem between the reign of Herod the Great and the destruction of the city in ad 70;

*they counted roughly 4,000 members most of whom lived in towns and settlements all over the country;

*they were a closely knit, well-organized, communitarian movement with separate branches, some of which were frightened of women and celibate at least at the priestly core of the movement, but not necessarily elsewhere.

*And, strikingly, they were admired for their lifestyle by other Jews and even by non-Jews.

Whatever the Dead Sea Scrolls and archaeology were to add to this picture after their rediscovery between 1947 and 1956, this, at any rate, is a nucleus of information which was already available for outinsiders in the diaspora before ad 50 (Philo of Alexandria), after the Roman occupation of Qumran in ad 68 and until 1947, when the first cave and its scrolls was rediscovered.

Later authors procured details of less certain origin. One of them is worth quoting, however, for he was a famous collector of source material which has not been preserved elsewhere. His name is Hippolytus, a Christian who lived from c. 170 to c. 236. He was a piesbyter in Rome and may even have been an anti-bishop or ‘pope’ to Callistus from ad 217 to 222. His most important writing, a Refutation Against All Heresies in ten books, was lost until Books 4 to 10 were rediscovered in a manuscript on Mount Athos, in the nineteenth century. It seems that Hippolytus knew the works of Josephus, since long passages look like a paraphrase of descriptions in the War and in the Antiquities; but he obviously had access to other sources about the Essenes which are no longer extant. Here is an example of the picture he draws:

They come together in one place, girding themselves with linen girdles to conceal their private parts. In this manner, they perform ablutions in cold water, and after being thus cleansed, they repair together into one apartment – no one who entertains a different opinion from themselves being with them in the house – and proceed to partake of breakfast. When they have taken their seats in order and in silence, the loaves are set out, and next some sort of food to eat along with it, and each receives from these a sufficient portion. No one, however, will taste these before the priest utters a prayer and blessing over them. After breakfast, he again says a prayer: as at the beginning, so at the conclusion of their meal they hymn God.23 Next, after they have laid aside as sacred the garments in which they have been clothed while together taking their repast within – now these garments are linen – and having resumed the clothes in the vestibule, they hasten to agreeable occupations until evening. They partake of supper, doing all things in like manner to those already mentioned. No one will at any time cry aloud, nor will any other tumultuous voice be heard, but they each converse quietly, and with decorum one concedes the conversation to the other, so that the stillness of those within appears a sort of mystery to those outside. They are invariably sober, both eating and drinking all things by measure.24

Towards the end of his depiction, he suddenly highlights an Essene teaching which the non-Jewish authors Pliny and Dion preferred to ignore (if they were aware of it, which we do not know for certain). Philo does not mention it either (for whatever reason), and Josephus, glancing at Greek mythology, plays it down with a certain sleight of hand: the Essenes’ belief in a bodily resurrection. Hippolytus writes,

The doctrine of the Resurrection has also derived support among them, for they acknowledge both that the flesh will rise again, and that it will be immortal, in the same manner as the soul is already imperishable. They maintain that when the soul has been separated from the body, it is now borne into one place, which is well ventilated and full of light, and there it rests until judgment. This locality the Greeks were acquainted with by hearsay, calling it Isles of the Blessed. But there are many other tenets of these men which the wise of the Greeks have appropriated and thus have from time to time formed their own opinions. For the discipline of these men in regard to the Divinity is of greater antiquity than that of all nations.25

Hippolytus goes on to argue that the Greeks and indeed everyone elsederived their concept of God and creation from Jewish thought. To him the Essenes were a kind of theological avant-garde, but at llie same time firmly based on ancestral teachings. More than 100 years after their disappearance from the stage of history, Hippolytus is the first Christian to regard them explicitly as kindred spirits at least in some of the central areas of the Jewish heritage which Christians and Essenes had in common. We shall see in Chapter VIII how a Qumran fragment, found in Cave 4 and numbered 4Q 521, does indeed deal with the question of the bodily resurrection, proving Hippolytus to be a trustworthy late classical source. It is one ol those fascinating cases where similarities between Essene theology and the teaching of Jesus are visible, going back to the same Old Testament passages, against the tenets of the priestly Sadducees who rejected it (Mark 12:18-27).

And there were still others who took notice of the Essenes. The lunatic followers of the messianic revolutionary Bar Kokhba, whose revolt led to an even more devastating destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in ad 135, had hideouts in the wadis and caves near Qumran. Looking at the ruins of the Essene settlement, they called it the ‘Castle of the Pious (toes’, or, in the original, Mezad Chasidim. As in modern Hebrew, a ‘hasid’ or ‘chasid’ (the initial letter is pronounced like the ch in Scottish Toch’) is 26 The Romans, who had occupied Qumran in ad 68,27 left this minor ‘outpost’ in the 111 ad-70s of the first century, after the fall of Masada, and about sixty years laer, some of the Essenes found refuge in their former barracks – previously the living quarters of the Essenes. The writer of the Wadi Murabba’ at letter tells his addressee he intends to go to this place and stay put. Most of his companions, he writes, had already been killed by the Romans. Seven Bar Kokhba coins were found in the settlement; but there is no trace of any attempt to reopen and use the caves.

The implicit admiration for the Essenes which can be detected in the attribute Chasidim – given the fact that Bar Kokhba himself was an orthodox, pious Jew – may have been caused by an enduring memory: the Essenes had fought valiantly against the Romans during the first revolt which ended with the destruction of their living quarters at Qumran in ad 68 and in Jerusalem in ad 70. One of them, called John the Essene, was a general in charge of the district of Thamna during that revolt – a fact which indicates that the Essenes had an accepted role to play in Jewish society, and they were no ultraorthodox fanatics who refused to have anything to do with the real world outside. John died in a failed attack on Askalon, held by the Romans, in ad 67. Josephus tells us how other Essenes suffered torture and death rather than giving in to Roman pressure to ‘blaspheme their legislator [God] or to eat what was forbidden to them [i.e. non-kosher food]’.28

end of page 28

p. 32

Can we place Jesus and his disciples somewhere among these fellow Jews? Jesus was a lifelong celibate, but most certainly not a misogynist. Women were among his followers; he encouraged them, honoured them and was honoured by them. In John’s Gospel, a woman, Mary of Magdala, was the first person to encounter the risen Christ. His decision against marriage was not a decision against the company of women. But since, in biblical terms, the purpose of marriage is the creation of a family, the Son of God was in a different category. From the point of view of sceptical onlookers, however – of people who may have accepted him as a rabbi, but not as the Son of God or the Messiah – his celibacy was unusual – still today, an unmarried rabbi would look like a walking contradiction in terms – but not impossible. The Torah, and Essene practice at his time, showed clearly it could be done. As for the disciples, they were married before they joined Jesus, left their families at his behest (Luke 18:28-29) and therefore became temporarily celibate, but returned to them in Galilee after the resurrection. As apostolic missionaries, they even took then- wives with them on their journeys (1 Corinthians 9:5). Paul later developed a personal teaching which he carefully describes as his own, and not ‘from the Lord’ (1 Corinthians 7:25-40): unmarried men and women should ideally remain unmarried, following his own example. He does not condemn marriage – far from it. But he thinks, and here he is very close to the Torah’s case in Exodus 19:15 and its interpretation by Ilie Essenes, that at a sanctified moment, at the end ‘of the world as we know it’ (1 Corinthians 7:29-31), marriage may be a distraction in one’s devotion to the Lord (7:35). Not many Jewish Christians followed his advice, it seems, in spite of his model and the Essene teaching of which quite a few Jews would have been aware. But we can see and understand it was not plainly absurd and typical of the (alleged) misogynist Paul, as critics of Paul’s attitude to women and marriage have often assumed. It had its place in contemporary Jewish thought and practice.

Encountering Essenes

Jesus, his disciples, and someone like Paul while still called Saul – or rather Sha’oul, the Pharisee – could have met Essenes anywhere, in Galilee, Samaria and Judea, in and around Jerusalem. There was certainly no need for them to go to Qumran if they wanted to find out who the Essenes were and what they taught. In Jerusalem, the ‘City of the Sanctuary’, Essenes were firmly established in New Testament times, so much so, that a small city gate on the south-west hill was called ‘Gate of the Essenes’ – a name duly recorded by Josephus.33 The gate has been re-excavated,34 and immediately behind it, on the hill which today is called Mount Zion, striking parallel purifying baths have been found, so-called mikvaoth, with further such mikvaoth, including the largest one ever found outside Qumran, in the vicinity. While purifying baths are not uncommon in Jewish towns, their number and architecture have been interpreted as typical of the Essenes who needed them for their frequent and daily self- purifications. What is more, Josephus links the Gate of the Essenes with a nearby bethso, which has been identified by historians as the latrines outside the city walls, again conforming to Essene rules.35

Josephus describes them in loving detail: he tells us the Essenes were not allowed to defecate on the seventh day and that they had to use mattocks to dig holes in the ground on the other days, at isolated sites (i.e. outside the confines of the settlement). ‘They squat there and are covered by their cloaks so that they do not offend the rays of God. Afterwards, they push back the dug-up soil into the hole… Although the evacuation of the excrements is natural, they are used to washing themselves afterwards [in purifying baths] as though defiled.’36

Concerning the gate, the mikvaoth and the bethso, recent archaeology has shown Josephus to be well informed. At the time of writing, a team led by the archaeologists James Strange and Bargil Pixner is preparing further excavations near the abbey of Hagia Maria Sion (formerly Dormition Abbey) on Mount Zion, looking for houses, further mikvaoth and other traces such as mattocks for the excrements which would provide additional evidence for the existence of an Essene quarter virtually next door to the first Christian living quarters in Jerusalem. A very recent discovery of some tombs outside the walls of the ancient city of Jerusalem, as yet unpublished, may further corroborate this link of Essenes with the city of Jerusalem: a number of male skeletons have been found which show exactly the same positioning as those found at Qumran.

The archaeology of Qumran and Jerusalem will be portrayed in a later chapter. One recent discovery, however, has to be mentioned at this stage: we have tacitly assumed that Pliny, Philo, Josephus and others knew what they were doing when they described the people living at Secacah as ‘Esseni’ or ‘Essaioi’, etc. If this word can be explained etymologically, from Aramaic hase, ‘pious’, as ‘the pious ones’, as most scholars think, it may well describe a form of outstanding devotion, much like the modern terms ‘Pietists’ and ‘Pietism’ have been used to describe a particular type of Protestant devotional life in southern Germany and some other parts of Europe. But not a single example of the use of this description has been found in long the Dead Sea Scrolls. Did the ‘Essenes’ themselves do without a proper name for themselves? Although they appear in the pages of the New Testament (see Chapter VII), we cannot identify them by name, because no name is given. In fact, those other messianic Jews, the Christians, had no group name of their own making, either, Strangers, observers in faraway Antioch, first had the idea to coin a phrase: they saw that those adherents of Jesus followed him as the Messiah, in Greek ‘the Christ’, and thus they were people ‘belonging lo Christ’, Christianoi, Christians (Acts 11:26). The Essenes, too, were named first by distant observers: by Philo and Pliny.

However, recently published fragments from Qumran may indicate that the Hebrew word was used among the Essenes, after all. They belong to a Levitic text in Aramaic from Cave 4, 4Q Levibar.37 In line 6, we read, ‘The name of the pious one(s) will for ever not be eradicated from their people.’ One might object that ‘pious ones’ is a somewhat general description in Aramaic, as in any other language – whereas ‘Essenes’ was as unique a derivative as ‘Pietists’. And indeed, in line 7, a different self-description of the movement occurs: they see themselves as the ‘holy ones from among the people’. Much like the early Christians’ self-description as followers of ‘the way’, these are communal labels, but they are not proper names. In 1996, a sensational discovery made not far from the steps to the plateau of Cave 7 presented a new possibility: a member of James Strange’s team excavating at Qumran found two ostraca (inscribed potsherds). The larger one, broken in two parts, contained fifteen damaged and fragmentary lines in a Hebrew script which paralleled the handwriting on the scrolls from the early first century ad. It mentions several people, among them a certain Honi from Jericho and his servant Hisdai. And in line 8, it appears to say that this Honi had fulfilled his oath towards the Yahad, or, in English, ‘Community’ or ‘Union’.38 The document looks like a contract transferring some of Honi’s possessions to the Yahad at Qumran. Since Yahad is a common term used in the Dead Sea Scrolls,39 it may now be possible to identify it as the proper name of the movement. After all, there is an outsider who calls them by this name in an official document. The only remaining problem is the definitive identification of line 8. Some critics have doubted that the damaged word can be read as Yahad, and the present author witnessed a heated discussion between Norman Golb and Esther Eshel (one of the editors of the ostraca) during the International Dead Sea Scrolls Congress at Jerusalem in the summer of 1997, which divided the audience. It seems that most professional palaeographers agree with Eshel’s reading – but more will be said (and published) in the foreseeable future.

Assuming that Yahad is indeed the solution to the quest for the Essene’s own proper name, we can even find its traces in the pages of the New Testament: in the Acts of the Apostles, Luke describes the first Christian community as a koinonia (Acts 2:42-44). This Greek word comes as close as any translation can to Yahad, ‘Community’ or ‘Union’. From other passages like Acts 5:1-11, which we will encounter later, it is obvious that the Christians in Jerusalem knew of Essene models of community discipline and were aware of a need to emulate those rigid standards if they wanted to convince their neighbours the Christian Yahad was the true one. Luke’s idiom, so early in this sequel to his gospel, may well contain an implicit claim: the Yahad/Koinonia must be understood as messianic. We, the Christians – still Jews – proclaim the one and only Messiah, Jesus. Therefore, our Yahad/Koinonia is the one to belong to, particularly for pious Jews. Not much later, in Acts 6:7, we may have a reference to the remarkable success of this strategy.40

If a close relationship between the Essenes and Jerusalem can be shown, both from archaeology and literature, what finally, and without going into details left to later chapters, can be said about the relationship between the Essene settlement at Qumran and the Qumran caves? Assuming the case for the identification of Qumran/Secacah with the settlement of the Essenes referred to by ancient authors is nvriwlielmingly strong, how strong is the case for their use of the Hives? What may look like an absurd question to most visitors who h.ivr seen the area of Qumran, is a far-from-settled one. Some obscure llicories, for which there is no shred of archaeological evidence, have mi ned Qumran into a fortress or into a winter villa, with inhabitants blissfully unaware of the library caves and their scrolls. Other scholars have assumed that the caves contained the library of the Temple, taken in I he caves near the Dead Sea for safe keeping just before the Roman onslaught on Jerusalem, and while Qumran was still active – that is, before ad 68. But the Temple library must have contained at least some representative writings of the Sadducees, the priestly movement in 11 large of Temple worship. So far, however, not a single Qumran scroll could be identified as undoubtedly Sadducean. Still others have denied any link between the Essenes and the caves and have treated the scrolls as a collection of different libraries, a kind of representative cross-section of Jewish theology. But it would be practically impossible to ignore a relationship between the inhabitants of Qumran and the caves: Caves 4, 5 and 6 were within a few hundred yards of the settlement, and their entrances were visible. No one could have approached them without being noticed by the inhabitants. Cave 7, the only cave with nothing but Greek texts exclusively on papyrus, was situated underneath the northern end of the plateau of Qumran. No one could reach it without going through the inhabited area. Remnants of the ancient steps to the cave can still be seen. Caves 8, 9 and 10 are also within walking distance of Qumran. That leaves only Caves 1, 2, 3 and 11 which could conceivably have been used unnoticed by the Qumran inhabitants. And since Cave 4 is the major library cave, with two-thirds of all scrolls, the very fact of its immediate vicinity to the settlement of Qumran is in itself a decisive argument against a separation of caves and Qumran Essenes.

Needless to say, this does not mean that the Essenes wrote all the texts found in these caves, or that they are a monolithic entity. We shall see later that some texts were certainly imported for study purposes.41 Others may represent a theological development among the Essene movement from its beginnings in the mid-second century bc to the mid-first century ad, when the last Hebrew and Aramaic scrolls were written. But as a rule, we should apply what the Qumran scholar and theologian, Frank M. Cross, put in a nutshell many years ago: ‘If the people of the scrolls were not the Essenes, they were a similar sect, living in the same centre, in the same area’.42 In other words, the logical working hypothesis is still to call them Essenes and treat them as directly involved with the caves and their scrolls. Alternative theories remind one of the old joke about the works of Shakespeare written by a different person of the same name. Or, to quote Cross again, any scholars who hesitate to identify the inhabitants of Qumran with the Essenes (and the use of the caves) place themselves in an astonishing position. For, as Cross states, with the acerbic pen of a long-suffering observer, such scholars

must suggest seriously that two major parties each formed communistic religious communities in the same district of the Dead Sea and lived together in effect for two centuries, holding similar bizarre views, performing similar or rather identical lustrations, ritual meals, and ceremonies. Further, the scholarjs] must suppose that one community, carefully described by classical authors, disappeared without leaving building remains or even potsherds behind; while the other community, systematically ignored by the classical sources, left extensive ruins and even a great library!43

Recent excavations by Yizhak Hirschfeld at En Gedi, not yet published,44 have led some observers to the risky hypothesis that the true Essene settlement was discovered, and that therefore Pliny the Elder’s account should be reinterpreted. His Essenes, Hirschfeld

suggested, did not live north of En Gedi (i.e. at Qumran/Secacah), but above it.45 Hirschfeld discovered some twenty-five houses of .11 (proximately two by three metres, the type of building one might associate with resident fieldworkers at the border of the oasis. There .tie not enough of them to house a community like the Essenes. And, so I ar, no traces of the typical mikvaoth, the numerous purifying baths demanded by the Essene Community Rule (and evident in abundance .it Qumran and near the Gate of the Essenes on Jerusalem’s southwest hill) have been found at the En Gedi site. Irrespective of the lack ol any evidence to prove that these archaeological traces can be identified with the period of Essene activities – they are probably early second century, some forty to fifty years after the destruction of the Essene sites by the Romans and the end of the Essene movement – there is an historical argument which should be taken into consideration. During the Jewish uprising against the Romans, which began in ad 66 and ended with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in ad 70, followed by Roman mopping-up operations including the conquest of the fortress of Masada in ad 73/74, some Essenes took refuge on that southern fortress. Their literature was known among the zealots; fragments of their texts, including the popular Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice,46 were discovered among the scant remains of the Masada library. Josephus, however, tells us that I he Masada defenders raided the settlement at En Gedi and killed the fellow Jewish inhabitants.47 It is inconceivable that they would have done so if the En Gedi area had been the Dead Sea headquarters of the Essenes.

Our sources, fragmentary as they are, may not tell us exactly what happened at Qumran and in Jerusalem, but they have already given us a multifaceted picture of a community which evolved and spread widely, around two centres: Qumran and, in New Testament times, the south-west hill of Jerusalem, and which seems to have allowed for a certain variety of lifestyles within the law. This last

insight may still prove helpful, since it widens the potential for contacts between Jesus, the Jews who followed Jesus during his life on earth and after his death and resurrection, and the Essenes. After all, if this movement was not uniform in appearance, in spite of a ‘hard kernel’ of shared regulations, if even such essential questions as that of celibacy versus married life with children could be dealt with differently, we must step back and look at the broader canvas. The whole question of an Essene influence on early Christianity, of common interests and parallel structures, and of unbridgeable differences, acquires refreshingly new perspectives.

End of Section I

To be continued….