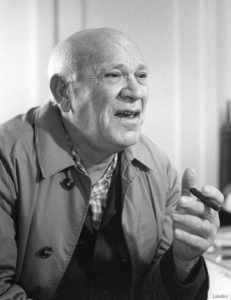

Eric Hoffer (July 15, 1902 – May 21, 1983) was an American moral and social philosopher. He was the author of ten books and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in February 1983. His first book, The True Believer (1951), was widely recognized as a classic, receiving critical acclaim from both scholars and laymen, although Hoffer believed that The Ordeal of Change (1963) was his finest work. The Eric Hoffer Book Award is an international literary prize established in his honor. Wikipedia

Eric Hoffer

“A mass movement attracts and holds a following not because it can satisfy the desire for self-advancement, but because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation.”

The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements is a non-fiction book authored by American philosopher Eric Hoffer. Published in 1951, it depicts a variety of arguments in terms of applied world history and social psychology to explain why mass movements arise to challenge the status quo. Hoffer discusses the sense of individual identity and the holding to particular ideals that can lead to fanaticism among both leaders and followers.

“Thus the differences between the conservative and the radical seem to spring mainly from their attitude toward the future. Fear of the future causes us to lean against and cling to the present, while faith in the future renders us receptive to change.”

Eric Hoffer – The True Believer

Hoffer initially attempts to explain the motives of the various types of personalities that give rise to mass movements in the first place and why certain efforts succeed while many others fail. He goes on to articulate a cyclical view of history such that why and how said movements start, progress and end is explored. Whether intended to be cultural, ideological, religious, or whatever else, Hoffer argues that mass movements are broadly interchangeable even when their stated goals or values differ dramatically. This makes sense, in the author’s view, given the frequent similarities between them in terms of the psychological influences on its adherents. Thus, many will often flip from one movement to another, Hoffer asserts, and the often shared motivations for participation entail practical effects. Since, whether radical or reactionary, the movements tend to attract the same sort of people in his view, the author describes them as fundamentally using the same tactics including possessing the rhetorical tools. As examples, he often refers to the purported political enemies of communism and fascism as well as the religions of Christianity and Islam. – Wikipedia

In 1938, Hoffer sent an article about tramps to a magazine. The magazine turned it down, but the editor kept in touch. A decade later, settled in San Francisco, Hoffer sent the woman a hand-written manuscript. She typed it, submitted it, and in 1951, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements was published. Its author was a middle-aged longshoreman hailed by the New York Times as “a genius against insuperable odds, capable of amazing insights into history.”

So who was Hoffer’s True Believer? In the age of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, he was the fresh convert to a cult of personality.

“The true believer is everywhere on the march,” Hoffer wrote. But tyrants, he cautioned, do not rule solely by coercion. True believers surrender their independence because it has gotten them nowhere. Disillusioned and defeated, they follow promises of greatness en masse. Fascism. Communism. Nationalism. Believe. Join. Trust us.

“The less justified a man is in claiming excellence for his own self,” Hoffer wrote, “the more ready he is to claim all excellence for his nation, his religion, his race or his holy cause.” Hmmm.

The True Believer made Hoffer’s name but not much money. He published more books — The Passionate State of Mind, The Ordeal of Change — but kept his job on the docks. On into the 1960s, he walked daily in Golden Gate Park, stopping to write in notebooks. Living alone in a small flat with no phone, no TV, he courted ideas. “I get the longshoremen mad when I say, ‘You know, I can’t think of anything more exciting than going to bed with a half-finished paragraph.’”

Amidst growing acclaim, Hoffer taught classes at Berkeley and wrote a syndicated column. LBJ consulted with him. Journalists sought his opinions. Finally, in 1967, Hoffer quit working and withdrew from public life. ‘I’m going to crawl back into my hole where I started,” he said. “I don’t want to be a public person or anybody’s spokesman. . . Any man can ride a train. Only a wise man knows when to get off.”

Hoffer died in 1983. He left behind nine books and 100+ notebooks now at Stanford’s Hoover Institute. But he also left a unique understanding of charismatic leaders and the followers who trade reason for blind faith. True believers, it seems, are still on the march and the longshoreman-philosopher can help us understand them.