“The conventions of our sense experience habituate us to the idea that light is always generated from a defined source, specific locus, or point in space. It is this presumption that permits us to perceive and conceive of defined or differentiated objects, space between objects, relative degrees of illumination, and also shadows. But, truly, all space, all locations, all objects are equally pervaded by true, original, or fundamental Light, Universal Energy, or Transcendental Radiance.”

Adi Da Samraj

***

SIX LECTURES ON

LIGHT

DELIVERED IN THE UNITED STATES

in 1872-1873

BY

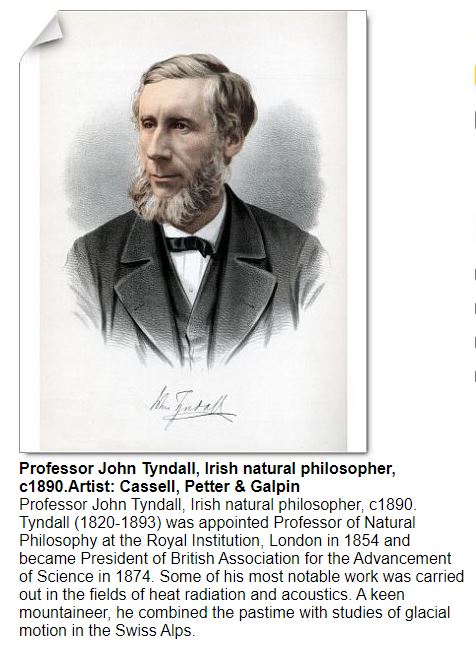

JOHN TYNDALL, D.C.L., LL,D., F.R.S.

LATE PROFESSOR OF NATURAL PHILOSOPHY IN THE ROYAL INSTITUTION OF GREAT BRITAIN

Summary and Conclusions

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

My desire in these lectures has been to show you, with as little breach of continuity as possible, something of the past growth and present aspect of a department of science, in which have laboured some of the greatest intellects the world has ever seen. I have sought to confer upon each experiment a distinct intellectual value, for experiments ought to be the representatives and expositors of thought—a language addressed to the eye as spoken words are to the ear. In association with its context, nothing is more impressive or instructive than a fit experiment; but, apart from its context, it rather suits the conjurer’s purpose of surprise, than the purpose of education which ought to be the ruling motive of the scientific man.

And now a brief summary of our work will not be out of place.

Our present mastery over the laws and phenomena of light has its origin in the desire of man to know. We have seen the ancients busy with this problem, but, like a child who uses his arms aimlessly, for want of the necessary muscular training, so these early men speculated vaguely and confusedly regarding natural phenomena, not having had the discipline needed to give clearness to their insight, and firmness to their grasp of principles. They assured themselves of the rectilineal propagation of light, and that the angle of incidence was equal to the angle of reflection. For more than a thousand years—I might say, indeed, for more than fifteen hundred years—the scientific intellect appears as if smitten with paralysis, the fact being that, during this time, the mental force, which might have run in the direction of science, was diverted into other directions.

The course of investigation, as regards light, was resumed in 1100 by an Arabian philosopher named Alhazen. Then it was taken up in succession by Roger Bacon, Vitellio, and Kepler. These men, though failing to detect the principles which ruled the facts, kept the fire of investigation constantly burning. Then came the fundamental discovery of Snell, that cornerstone of optics, as I have already called it, and immediately afterwards we have the application, by Descartes, of Snell’s discovery to the explanation of the rainbow. Following this we have the overthrow, by Roemer, of the notion of Descartes, that light was transmitted instantaneously through space. Then came Newton’s crowning experiments on the analysis and synthesis of white light, by which it was proved to be compounded of various kinds of light of different degrees of refrangibility.

Up to his demonstration of the composition of white light, Newton had been everywhere triumphant—triumphant in the heavens, triumphant on the earth, and his subsequent experimental work is, for the most part, of immortal value. But infallibility is not an attribute of man, and, soon after his discovery of the nature of white light, Newton proved himself human. He supposed that refraction and chromatic dispersion went hand in hand, and that you could not abolish the one without at the same time abolishing the other. Here Dollond corrected him.

But Newton committed a graver error than this. Science, as I sought to make clear to you in our second lecture, is only in part a thing of the senses. The roots of phenomena are embedded in a region beyond the reach of the senses, and less than the root of the matter will never satisfy the scientific mind. We find, accordingly, in this career of optics the greatest minds constantly yearning to break the bounds of the senses, and to trace phenomena to their subsensible foundation. Thus impelled, they entered the region of theory, and here Newton, though drawn from time to time towards truth, was drawn still more strongly towards error; and he made error his substantial choice. His experiments are imperishable, but his theory has passed away. For a century it stood like a dam across the course of discovery; but, as with all barriers that rest upon authority, and not upon truth, the pressure from behind increased, and eventually swept the barrier away.

In 1808 Malus, looking through Iceland spar at the sun, reflected from the window of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, discovered the polarization of light by reflection. As stated at the time, this discovery ushered in the darkest hour in the fortunes of the wave theory. But the darkness did not continue. In 1811 Arago discovered the splendid chromatic phenomena which we have had illustrated by the deportment of plates of gypsum in polarized light; he also discovered the rotation of the plane of polarization by quartz-crystals. In 1813 Seebeck discovered the polarization of light by tourmaline. That same year Brewster discovered those magnificent bands of colour that surround the axes of biaxal crystals. In 1814 Wollaston discovered the rings of Iceland spar. All these effects, which, without a theoretic clue, would leave the human mind in a jungle of phenomena without harmony or relation, were organically connected by the theory of undulation.

The wave theory was applied and verified in all directions, Airy being especially conspicuous for the severity and conclusiveness of his proofs. A most remarkable verification fell to the lot of the late Sir William Hamilton, of Dublin, who, taking up the theory where Fresnel had left it, arrived at the conclusion that at four special points of the ‘wave-surface’ in double-refracting crystals, the ray was divided, not into two parts but into an infinite number of parts; forming at these points a continuous conical envelope instead of two images. No human eye had ever seen this envelope when Sir William Hamilton inferred its existence. He asked Dr. Lloyd to test experimentally the truth of his theoretic conclusion. Lloyd, taking a crystal of arragonite, and following with the most scrupulous exactness the indications of theory, cutting the crystal where theory said it ought to be cut, observing it where theory said it ought to be observed, discovered the luminous envelope which had previously been a mere idea in the mind of the mathematician.

Nevertheless, this great theory of undulation, like many another truth, which in the long run has proved a blessing to humanity, had to establish, by hot conflict, its right to existence. Illustrious names were arrayed against it. It had been enunciated by Hooke, it had been expounded and applied by Huyghens, it had been defended by Euler. But they made no impression. And, indeed, the theory in their hands lacked the strength of a demonstration. It first took the form of a demonstrated verity in the hands of Thomas Young. He brought the waves of light to bear upon each other, causing them to support each other, and to extinguish each other at will. From their mutual actions he determined their lengths, and applied his knowledge in all directions. He finally showed that the difficulty of polarization yielded to the grasp of theory.

After him came Fresnel, whose transcendent mathematical abilities enabled him to give the theory a generality unattained by Young. He seized it in its entirety; followed the ether into the hearts of crystals of the most complicated structure, and into bodies subjected to strain and pressure. He showed that the facts discovered by Malus, Arago, Brewster, and Biot were so many ganglia, so to speak, of his theoretic organism, deriving from it sustenance and explanation. With a mind too strong for the body with which it was associated, that body became a wreck long before it had become old, and Fresnel died, leaving, however, behind him a name immortal in the annals of science.

One word more I should like to say regarding Fresnel. There are things better even than science. Character is higher than Intellect, but it is especially pleasant to those who wish to think well of human nature when high intellect and upright character are found combined. They were combined in this young Frenchman. In those hot conflicts of the undulatory theory, he stood forth as a man of integrity, claiming no more than his right, and ready to concede their rights to others. He at once recognized and acknowledged the merits of Thomas Young. Indeed, it was he, and his fellow-countryman Arago, who first startled England into the consciousness of the injustice done to Young in the ‘Edinburgh Review.’

I should like to read to you a brief extract from a letter written by Fresnel to Young in 1824, as it throws a pleasant light upon the character of the French philosopher. ‘For a long time,’ says Fresnel, ‘that sensibility, or that vanity, which people call love of glory has been much blunted in me. I labour much less to catch the suffrages of the public, than to obtain that inward approval which has always been the sweetest reward of my efforts. Without doubt, in moments of disgust and discouragement, I have often needed the spur of vanity to excite me to pursue my researches. But all the compliments I have received from Arago, De la Place, and Biot never gave me so much pleasure as the discovery of a theoretic truth or the confirmation of a calculation by experiment.’

This, then, is the core of the whole matter as regards science. It must be cultivated for its own sake, for the pure love of truth, rather than for the applause or profit that it brings. And now my occupation in America is well-nigh gone. Still I will bespeak your tolerance for a few concluding remarks, in reference to the men who have bequeathed to us the vast body of knowledge of which I have sought to give you some faint idea in these lectures. What was the motive that spurred them on? What urged them to those battles and those victories over reticent Nature, which have become the heritage of the human race? It is never to be forgotten that not one of those great investigators, from Aristotle down to Stokes and Kirchhoff, had any practical end in view, according to the ordinary definition of the word ‘practical.’ They did not propose to themselves money as an end, and knowledge as a means of obtaining it. For the most part, they nobly reversed this process, made knowledge their end, and such money as they possessed the means of obtaining it.

We see to-day the issues of their work in a thousand practical forms, and this may be thought sufficient to justify, if not ennoble, their efforts. But they did not work for such issues; their reward was of a totally different kind. In what way different? We love clothes, we love luxuries, we love fine equipages, we love money, and any man who can point to these as the result of his efforts in life, justifies these results before all the world. In America and England, more especially, he is a ‘practical’ man. But I would appeal confidently to this assembly whether such things exhaust the demands of human nature? The very presence here for six inclement nights of this great audience, embodying so much of the mental force and refinement of this vast city, is an answer to my question. I need not tell such an assembly that there are joys of the intellect as well as joys of the body, or that these pleasures of the spirit constituted the reward of our great investigators. Led on by the whisperings of natural truth, through pain and self-denial, they often pursued their work. With the ruling passion strong in death, some of them, when no longer able to hold a pen, dictated to their friends the last results of their labours, and then rested from them forever.

Could we have seen these men at work, without any knowledge of the consequences of their work, what should we have thought of them? To the uninitiated, in their day, they might often appear as big children playing with soap-bubbles and other trifles. It is so to this hour. Could you watch the true investigator—your Henry or your Draper, for example—in his laboratory, unless animated by his spirit, you could hardly understand what keeps him there. Many of the objects which rivet his attention might appear to you utterly trivial; and if you were to ask him what is the use of his work, the chances are that you would confound him. He might not be able to express the use of it in intelligible terms. He might not be able to assure you that it will put a dollar into the pocket of any human being present or to come. That scientific discovery may put not only dollars into the pockets of individuals, but millions into the exchequers of nations, the history of science amply proves; but the hope of its doing so never was, and it never can be, the motive power of the investigator.

I know that some risk is run in speaking thus before practical men. I know what De Tocqueville says of you. ‘The man of the North,’ he says, ‘has not only experience, but knowledge. He, however, does not care for science as a pleasure, and only embraces it with avidity when it leads to useful applications.’ But what, I would ask, are the hopes of useful applications which have caused you so many times to fill this place, in spite of snow-drifts and biting cold? What, I may ask, is the origin of that kindness which drew me from my work in London to address you here, and which, if I permitted it, would send me home a millionaire? Not because I had taught you to make a single cent by science am I here to-night, but because I tried to the best of my ability to present science to the world as an intellectual good. Surely no two terms were ever so distorted and misapplied with reference to man, in his higher relations, as these terms useful and practical. Let us expand our definitions until they embrace all the needs of man, his highest intellectual needs inclusive. It is specially on this ground of its administering to the higher needs of the intellect; it is mainly because I believe it to be wholesome, not only as a source of knowledge but as a means of discipline, that I urge the claims of science upon your attention.

But with reference to material needs and joys, surely pure science has also a word to say. People sometimes speak as if steam had not been studied before James Watt, or electricity before Wheatstone and Morse; whereas, in point of fact, Watt and Wheatstone and Morse, with all their practicality, were the mere outcome of antecedent forces, which acted without reference to practical ends. This also, I think, merits a moment’s attention. You are delighted, and with good reason, with your electric telegraphs, proud of your steam-engines and your factories, and charmed with the productions of photography. You see daily, with just elation, the creation of new forms of industry—new powers of adding to the wealth and comfort of society. Industrial England is heaving with forces tending to this end; and the pulse of industry beats still stronger in the United States. And yet, when analyzed, what are industrial America and industrial England?

If you can tolerate freedom of speech on my part, I will answer this question by an illustration. Strip a strong arm, and regard the knotted muscles when the hand is clenched and the arm bent. Is this exhibition of energy the work of the muscle alone? By no means. The muscle is the channel of an influence, without which it would be as powerless as a lump of plastic dough. It is the delicate unseen nerve that unlocks the power of the muscle. And without those filaments of genius, which have been shot like nerves through the body of society by the original discoverer, industrial America, and industrial England, would be very much in the condition of that plastic dough.

At the present time there is a cry in England for technical education, and it is a cry in which the most commonplace intellect can join, its necessity is so obvious. But there is no such cry for original investigation. Still, without this, as surely as the stream dwindles when the spring dies, so surely will ‘technical education’ lose all force of growth, all power of reproduction. Our great investigators have given us sufficient work for a time; but if their spirit die out, we shall find ourselves eventually in the condition of those Chinese mentioned by De Tocqueville, who, having forgotten the scientific origin of what they did, were at length compelled to copy without variation the inventions of an ancestry wiser than themselves, who had drawn their inspiration direct from Nature.

Both England and America have reason to bear those things in mind, for the largeness and nearness of material results are only too likely to cause both countries to forget the small spiritual beginnings of such results, in the mind of the scientific discoverer. You multiply, but he creates. And if you starve him, or otherwise kill him—nay, if you fail to secure for him free scope and encouragement—you not only lose the motive power of intellectual progress, but infallibly sever yourselves from the springs of industrial life.

What has been said of technical operations holds equally good for education, for here also the original investigator constitutes the fountain-head of knowledge. It belongs to the teacher to give this knowledge the requisite form; an honourable and often a difficult task. But it is a task which receives its final sanctification, when the teacher himself honestly tries to add a rill to the great stream of scientific discovery. Indeed, it may be doubted whether the real life of science can be fully felt and communicated by the man who has not himself been taught by direct communion with Nature. We may, it is true, have good and instructive lectures from men of ability, the whole of whose knowledge is second-hand, just as we may have good and instructive sermons from intellectually able and unregenerate men. But for that power of science, which corresponds to what the Puritan fathers would call experimental religion in the heart, you must ascend to the original investigator.

To keep society as regards science in healthy play, three classes of workers are necessary: Firstly, the investigator of natural truth, whose vocation it is to pursue that truth, and extend the field of discovery for the truth’s own sake and without reference to practical ends. Secondly, the teacher of natural truth, whose vocation it is to give public diffusion to the knowledge already won by the discoverer. Thirdly, the applier of natural truth, whose vocation it is to make scientific knowledge available for the needs, comforts, and luxuries of civilized life. These three classes ought to co-exist and interact. Now, the popular notion of science, both in this country and in England, often relates not to science strictly so called, but to the applications of science. Such applications, especially on this continent, are so astounding—they spread themselves so largely and umbrageously before the public eye—that they often shut out from view those workers who are engaged in the quieter and profounder business of original investigation.

Take the electric telegraph as an example, which has been repeatedly forced upon my attention of late. I am not here to attenuate in the slightest degree the services of those who, in England and America, have given the telegraph a form so wonderfully fitted for public use. They earned a great reward, and they have received it. But I should be untrue to you and to myself if I failed to tell you that, however high in particular respects their claims and qualities may be, your practical men did not discover the electric telegraph. The discovery of the electric telegraph implies the discovery of electricity itself, and the development of its laws and phenomena. Such discoveries are not made by practical men, and they never will be made by them, because their minds are beset by ideas which, though of the highest value from one point of view, are not those which stimulate the original discoverer.

The ancients discovered the electricity of amber; and Gilbert, in the year 1600, extended the discovery to other bodies. Then followed Boyle, Von Guericke, Gray, Canton, Du Fay, Kleist, Cunæus, and your own Franklin. But their form of electricity, though tried, did not come into use for telegraphic purposes. Then appeared the great Italian Volta, who discovered the source of electricity which bears his name, and applied the most profound insight, and the most delicate experimental skill to its development. Then arose the man who added to the powers of his intellect all the graces of the human heart, Michael Faraday, the discoverer of the great domain of magneto-electricity. Hans Oersted discovered the deflection of the magnetic needle, and Arago and Sturgeon the magnetization of iron by the electric current. The voltaic circuit finally found its theoretic Newton in Ohm; while Henry, of Princeton, who had the sagacity to recognize the merits of Ohm while they were still decried in his own country, was at this time in the van of experimental inquiry.

In the works of these men you have all the materials employed at this hour, in all the forms of the electric telegraph. Nay, more; Gauss, the illustrious astronomer, and Weber, the illustrious natural philosopher, both professors in the University of Göttingen, wishing to establish a rapid mode of communication between the observatory and the physical cabinet of the university, did this by means of an electric telegraph. Thus, before your practical men appeared upon the scene, the force had been discovered, its laws investigated and made sure, the most complete mastery of its phenomena had been attained—nay, its applicability to telegraphic purposes demonstrated—by men whose sole reward for their labours was the noble excitement of research, and the joy attendant on the discovery of natural truth.

Are we to ignore all this? We do so at our peril. For I say again that, behind all our practical applications, there is a region of intellectual action to which practical men have rarely contributed, but from which they draw all their supplies. Cut them off from this region, and they become eventually helpless. In no case is the adage truer, ‘Other men laboured, but ye are entered into their labours,’ than in the case of the discoverer and applier of natural truth. But now a word on the other side. While practical men are not the men to make the necessary antecedent discoveries, the cases are rare, though, in our day, not absent, in which the discoverer knows how to turn his labours to practical account. Different qualities of mind and habits of thought are usually needed in the two cases; and while I wish to give emphatic utterance to the claims of those whose position, owing to the simple fact of their intellectual elevation, is often misunderstood, I am not here to exalt the one class of workers at the expense of the other. They are the necessary complements of each other. But remember that one class is sure to be taken care of. All the material rewards of society are already within their reach, while that same society habitually ascribes to them intellectual achievements which were never theirs. This cannot but act to the detriment of those studies out of which, not only our knowledge of nature, but our present industrial arts themselves, have sprung, and from which the rising genius of the country is incessantly tempted away.

Pasteur, one of the most illustrious members of the Institute of France, in accounting for the disastrous overthrow of his country, and the predominance of Germany in the late war, expresses himself thus: ‘Few persons comprehend the real origin of the marvels of industry and the wealth of nations. I need no further proof of this than the employment, more and more frequent, in official language, and in writings of all sorts, of the erroneous expression applied science. The abandonment of scientific careers by men capable of pursuing them with distinction, was recently deplored in the presence of a minister of the greatest talent. The statesman endeavoured to show that we ought not to be surprised at this result, because in our day the reign of theoretic science yielded place to that of applied science. Nothing could be more erroneous than this opinion, nothing, I venture to say, more dangerous, even to practical life, than the consequences which might flow from these words. They have rested in my mind as a proof of the imperious necessity of reform in our superior education. There exists no category of the sciences, to which the name of applied science could be rightly given. We have science, and the applications of science, which are united together as the tree and its fruit.’

And Cuvier, the great comparative anatomist, writes thus upon the same theme: ‘These grand practical innovations are the mere applications of truths of a higher order, not sought with a practical intent, but pursued for their own sake, and solely through an ardour for knowledge. Those who applied them could not have discovered them; but those who discovered them had no inclination to pursue them to a practical end. Engaged in the high regions whither their thoughts had carried them, they hardly perceived these practical issues though born of their own deeds. These rising workshops, these peopled colonies, those ships which furrow the seas—this abundance, this luxury, this tumult—all this comes from discoveries in science, and it all remains strange to the discoverers. At the point where science merges into practice they abandon it; it concerns them no more.’

When the Pilgrim Fathers landed at Plymouth Rock, and when Penn made his treaty with the Indians, the new-comers had to build their houses, to cultivate the earth, and to take care of their souls. In such a community science, in its more abstract forms, was not to be thought of. And at the present hour, when your hardy Western pioneers stand face to face with stubborn Nature, piercing the mountains and subduing the forest and the prairie, the pursuit of science, for its own sake, is not to be expected. The first need of man is food and shelter; but a vast portion of this continent is already raised far beyond this need. The gentlemen of New York, Brooklyn, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington have already built their houses, and very beautiful they are; they have also secured their dinners, to the excellence of which I can also bear testimony. They have, in fact, reached that precise condition of well-being and independence when a culture, as high as humanity has yet reached, may be justly demanded at their hands. They have reached that maturity, as possessors of wealth and leisure, when the investigator of natural truth, for the truth’s own sake, ought to find among them promoters and protectors.

Among the many problems before them they have this to solve, whether a republic is able to foster the highest forms of genius. You are familiar with the writings of De Tocqueville, and must be aware of the intense sympathy which he felt for your institutions; and this sympathy is all the more valuable from the philosophic candour with which he points out not only your merits, but your defects and dangers. Now if I come here to speak of science in America in a critical and captious spirit, an invisible radiation from my words and manner will enable you to find me out, and will guide your treatment of me to-night. But if I in no unfriendly spirit—in a spirit, indeed, the reverse of unfriendly—venture to repeat before you what this great historian and analyst of democratic institutions said of America, I am persuaded that you will hear me out. He wrote some three and twenty years ago, and, perhaps, would not write the same to-day; but it will do nobody any harm to have his words repeated, and, if necessary, laid to heart.

In a work published in 1850, De Tocqueville says: ‘It must be confessed that, among the civilized peoples of our age, there are few in which the highest sciences have made so little progress as in the United States. He declares his conviction that, had you been alone in the universe, you would soon have discovered that you cannot long make progress in practical science without cultivating theoretic science at the same time. But, according to De Tocqueville, you are not thus alone. He refuses to separate America from its ancestral home; and it is there, he contends, that you collect the treasures of the intellect, without taking the trouble to create them.

De Tocqueville evidently doubts the capacity of a democracy to foster genius as it was fostered in the ancient aristocracies. ‘The future,’ he says, ‘will prove whether the passion for profound knowledge, so rare and so fruitful, can be born and developed as readily in democratic societies as in aristocracies. For my part,’ he continues, ‘I can hardly believe it.’ He speaks of the unquiet feverishness of democratic communities, not in times of great excitement, for such times may give an extraordinary impetus to ideas, but in times of peace. There is then, he says, ‘a small and uncomfortable agitation, a sort of incessant attrition of man against man, which troubles and distracts the mind without imparting to it either loftiness or animation.’ It rests with you to prove whether these things are necessarily so—whether scientific genius cannot find, in the midst of you, a tranquil home.

I should be loth to gainsay so keen an observer and so profound a political writer, but, since my arrival in this country, I have been unable to see anything in the constitution of society, to prevent a student, with the root of the matter in him, from bestowing the most steadfast devotion on pure science. If great scientific results are not achieved in America, it is not to the small agitations of society that I should be disposed to ascribe the defect, but to the fact that the men among you who possess the endowments necessary for profound scientific inquiry, are laden with duties of administration, or tuition, so heavy as to be utterly incompatible with the continuous and tranquil meditation which original investigation demands. It may well be asked whether Henry would have been transformed into an administrator, or whether Draper would have forsaken science to write history, if the original investigator had been honoured as he ought to be in this land. I hardly think they would. Still I do not imagine this state of things likely to last. In America there is a willingness on the part of individuals to devote their fortunes, in the matter of education, to the service of the commonwealth, which is probably without a parallel elsewhere; and this willingness requires but wise direction to enable you effectually to wipe away the reproach of De Tocqueville.

Your most difficult problem will be, not to build institutions, but to discover men. You may erect laboratories and endow them; you may furnish them with all the appliances needed for inquiry; in so doing you are but creating opportunity for the exercise of powers which come from sources entirely beyond your reach. You cannot create genius by bidding for it. In biblical language, it is the gift of God; and the most you could do, were your wealth, and your willingness to apply it, a million-fold what they are, would be to make sure that this glorious plant shall have the freedom, light, and warmth necessary for its development. We see from time to time a noble tree dragged down by parasitic runners. These the gardener can remove, though the vital force of the tree itself may lie beyond him: and so, in many a case you men of wealth can liberate genius from the hampering toils which the struggle for existence often casts around it.

Drawn by your kindness, I have come here to give these lectures, and now that my visit to America has become almost a thing of the past, I look back upon it as a memory without a single stain. No lecturer was ever rewarded as I have been. From this vantage-ground, however, let me remind you that the work of the lecturer is not the highest work; that in science, the lecturer is usually the distributor of intellectual wealth amassed by better men. And though lecturing and teaching, in moderation, will in general promote their moral health, it is not solely or even chiefly, as lecturers, but as investigators, that your highest men ought to be employed. You have scientific genius amongst you—not sown broadcast, believe me, it is sown thus nowhere—but still scattered here and there. Take all unnecessary impediments out of its way. Keep your sympathetic eye upon the originator of knowledge. Give him the freedom necessary for his researches, not overloading him, either with the duties of tuition or of administration, nor demanding from him so-called practical results—above all things, avoiding that question which ignorance so often addresses to genius: ‘What is the use of your work?’ Let him make truth his object, however unpractical for the time being it may appear. If you cast your bread thus upon the waters, be assured it will return to you, though it be after many days.