“Schlegel believed the Germans, Greeks, and Romans inherited their religious ideas and political organization from India.“

“The new study of India would not be merely an extension of the older Renaissance. It would also bring a reversal, or at least a correction of the outcome of the exaggerated preoccupation with Greece.”

***

ABSTRACT

India and the Identity of Europe: The Case of Friedrich Schlegel

January 2006, Journal of the History of Ideas 67(4):713-734

DOI: 10.1353/jhi.2006.0029

Authors: Chen Tzoref-Ashkenazi

“If only Indian studies could find such cultivators and patrons as in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries suddenly kindled in Italy and Germany an ardent appreciation of Greek studies, and in so short a time achieved so much that the reawakened knowledge of antiquity changed and rejuvenated wisdom and science, indeed one could even say the world itself. Not less grand and universal, I dare to assert, would be the effect of Indian studies even now, if it were seized with similar force and introduced into the circle of European learning.”

These enthusiastic words were used by Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829) to recommend the study of Indian literature to the readers of his 1808 Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier.

In this book, Schlegel offered the fruits of his studies of Sanskrit and Indian literature, which began in Paris in 1803. Here he introduced to the educated public of Continental Europe the theory about the affinity of Sanskrit to Greek, Latin and German, twenty-two years after this theory, which is now called “the Indo-European relationship,” was presented by Sir William Jones to the members of the Asiatick Society in Calcutta.

The presentation of this linguistic relationship, together with a call to study languages by a historical-comparative method, comprised the first part of the book. The second part dealt with Indian philosophy, which according to Schlegel, belonged to the tradition of all Oriental philosophy. The third part suggested how the study of Indian literature might benefit the study of history in general.

“Central to this view was the speculation that Indian civilization had emigrated to Europe, supported by the linguistic affinity between Sanskrit and European languages.”

Central to this view was the speculation that Indian civilization had emigrated to Europe, supported by the linguistic affinity between Sanskrit and European languages. The recommendation in the quotation above was well received. The publication of Schlegel’s book excited the intellectual community of continental Europe, and, by 1809, large parts of the book had appeared in French translation. The most important outcome of this excitement was the arrival of Franz Bopp and August Wilhelm Schlegel, Friedrich’s elder brother, in Paris to study Sanskrit.

The excitement stirred by Schlegel’s book reflected the growing interest in India and the East among European intellectuals. This was a very complex process that was a product of Europe’s growing colonial power in Asia but was also a part of the modernization of European thought. Interest in India swelled during the last third of the eighteenth century, as the British were becoming the dominant power in the subcontinent and began collecting, analyzing, and distributing information on Indian civilization, mainly through the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, which was established by William Jones in 1783 under the patronage of the Governor-General Warren Hastings.

What interested European intellectuals most about the ancient cultures of India and other oriental countries, was what they could learn about the ancient religions of these countries. The region from Egypt to India was thought to be the “cradle of humanity,” with various thinkers believing the “Urheimat” to be in another center of oriental civilization, be it Egypt, Mesopotamia or Persia. India became popular with the publication of John Holwell’s Interesting Historical Events Relating to Bengal in 1765, which was the main source for Voltaire’s ideas on India. Statements concerning the nature of Hinduism became important arguments in theological debates in Europe and were used in the critique of Christianity both from within and from outside. Critics of established religion like Voltaire argued that the antiquity of Hinduism and its alleged Monotheism show Christianity to be a late invention. Supporters of orthodox Christianity argued, with Thomas Maurice in England and Friedrich Stolberg in Germany, that the very antiquity of Hinduism and its resemblance to Christianity prove the divine origin of the bible.

This kind of interest in India was growing fast especially in Germany during the first decade of the nineteenth century. A favorite theme for philosophers and theologians was the comparative history of mythology, which would generally compare Egyptian, Indian, Greek, Persian, Babylonian, Phoenician and sometimes Germanic mythology to Christianity and show them to be one and the same system.

India and the Identity of Europe: The Case of Friedrich Schlegel

Author: Chen Tzoref-Ashkenazi

Source: Journal of the History of Ideas , Oct., 2006, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Oct., 2006), pp. 713- 734

Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30141054

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

India and the Identity of Europe:

The Case of Friedrich Schlegel

Chen Tzoref-Ashkenazi

Israeli historian Chen Tzoref-Ashkenazi, born in 1963, studied in Tel Aviv and is currently visiting researcher at the South Asia Institute of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg.

“If only Indian studies could find such cultivators and patrons as

in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries suddenly kindled in Italy

and Germany an ardent appreciation of Greek studies, and in so

short a time achieved so much that the reawakened knowledge of

antiquity changed and rejuvenated wisdom and science, indeed

one could even say the world itself. Not less grand and universal,

I dare to assert, would be the effect of Indian studies even now, if

it were seized with similar force and introduced into the circle of

European learning.'”2

I

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel, born 10 March 1772 and died 12 January 1829, was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist and indologist.

***

This article is based on a paper presented at the second International Convention of Asian Scholars, held at the Freie Universitit, Berlin, in August 2001. The research formed a part of the Ph.D. dissertation “The Indo-Germanic Connection: Friedrich Schlegel’s Search for the Origin of the Germans from India” that was submitted to the School of History of Tel Aviv University. I am deeply grateful to my tutor, Joseph Mali, for his invaluable contribution to my work. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewer of the Journal of the History of Ideas for very useful comments.

2 “M6chte das indische Studium nur einige solche Anbauer und Begtinstiger finden, wiederen Italien und Deutschland im ftinfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhundert ftir das griechische Studium so manche sich pl6tzlich erheben und in kurzer Zeit so Grofges leistensah; indem durch die wiedererweckte Kenntnis des Altertums schnell die Gestalt aller

Wissenschaften, ja man kann wohl sagen der Welt, verandert und verjtingt ward. Nicht weniger grogf und allgemein, wir wagen es zu behaupten, wiirde auch jetzt die Wirkung des indischen Studiums sein, wenn es mit eben der Kraft ergriffen, und in den Kreis der europaischen Kenntnisse eingefohrt wurde.” Friedrich Schlegel, Kritische Friedrich

Schlegel Ausgabe (KA), ed. Ernst Behler et al. (Paderborn: Sch6ningh, 1958-), 8: 111; The Copyright by Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 67, Number 4 (October 2006)

***

![]() hese enthusiastic words were used by Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) to recommend the study of Indian literature to the readers of his 1808 Uber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier.3 In this book, Schlegel offered the fruits of his studies of Sanskrit and Indian literature, which began in Paris in 1803. Here he introduced to the educated public of Continental Europe the theory about the affinity of Sanskrit to Greek, Latin and German, twenty-two years after this theory, which is now called “the Indo-European relationship,” was presented by Sir William Jones to the members of the Asiatick Society in Calcutta. The presentation of this linguistic relationship, together with a call to study languages by a historical-comparative method, comprised the first part of the book. The second part dealt with Indian philosophy, which according to Schlegel, belonged to the tradition of all Oriental philosophy. The third part suggested how the study of Indian literature might benefit the study of history in general. Central to this view was

hese enthusiastic words were used by Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) to recommend the study of Indian literature to the readers of his 1808 Uber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier.3 In this book, Schlegel offered the fruits of his studies of Sanskrit and Indian literature, which began in Paris in 1803. Here he introduced to the educated public of Continental Europe the theory about the affinity of Sanskrit to Greek, Latin and German, twenty-two years after this theory, which is now called “the Indo-European relationship,” was presented by Sir William Jones to the members of the Asiatick Society in Calcutta. The presentation of this linguistic relationship, together with a call to study languages by a historical-comparative method, comprised the first part of the book. The second part dealt with Indian philosophy, which according to Schlegel, belonged to the tradition of all Oriental philosophy. The third part suggested how the study of Indian literature might benefit the study of history in general. Central to this view was

the speculation that Indian civilization had emigrated to Europe, supported by the linguistic affinity between Sanskrit and European languages.

The recommendation in the quotation above was well received. The publication of Schlegel’s book excited the intellectual community of continental Europe, and, by 1809, large parts of the book had appeared in French translation.4 The most important outcome of this excitement was the arrival of Franz Bopp and August Wilhelm Schlegel, Friedrich’s elder brother, in Paris to study Sanskrit. The excitement stirred by Schlegel’s book reflected the growing interest in India and the East among European intellectuals. This was a very complex process that was a product of Europe’s growing colonial power in Asia but was also a part of the modernization of European thought. Interest in India swelled during the last third of the eighteenth century, as the British were becoming the dominant power in the subcontinent and began collecting, analyzing, and distributing information on Indian civilization, mainly through the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, which was established by William Jones in 1783 under the patronage of the Governor-General Warren Hastings.

—————

5 aesthetic and miscellaneous works of Frederick von Schlegel, trans. Ellen J Millington (London: Bohn, 1860), 427.

3 Schlegel, Uber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier: ein Beitrag zur Begriindung der

Altertumskunde, nebst metrischen Uebersetzungen indischer Gedichte (Heidelberg: Mohr

und Zimmer, 1808).

4 J. Magnet, Essai sur la premiere formation des langues, et sur la difference du genie des

langues originales et des langues composees; Trad. de l’anglais … Avec des notes ; Suivi

du premier livre des Recherches sur la langue et la philosophie des Indiens. Extrait et

traduit de l’allemand de F. Schlegel (Geneva: Manget et Cherbuliez, 1809).

P5 . J. Marshall, “Introduction,” in The British Discovery of Hinduism in the Eighteenth

Century, ed. P. J. Marshall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

“Critics of established religion like Voltaire argued that the antiquity of Hinduism and its alleged Monotheism show Christianity to be a late invention”

What interested European intellectuals most about the ancient cultures of India and other oriental countries, was what they could learn about the ancient religions of these countries. The region from Egypt to India was thought to be the “cradle of humanity,” with various thinkers believing the “Urheimat” to be in another center of oriental civilization, be it Egypt, Mesopotamia or Persia. India became popular with the publication of John Holwell’s Interesting Historical Events Relating to Bengal in 1765,6 which was the main source for Voltaire’s ideas on India.7 Statements concerning the nature of Hinduism became important arguments in theological debates in Europe and were used in the critique of Christianity both from within and from outside. Critics of established religion like Voltaire argued that the antiquity of Hinduism and its alleged Monotheism show Christianity to be a late invention.8 Supporters of orthodox Christianity argued, with Thomas Maurice in England9 and Friedrich Stolberg in Germany,10 that the very antiquity of Hinduism and its resemblance to Christianity prove the divine origin of the bible.

This kind of interest in India was growing fast especially in Germany during the first decade of the nineteenth century. A favorite theme for philosophers and theologians was the comparative history of mythology, which would generally compare Egyptian, Indian, Greek, Persian, Babylonian, Phoenician and sometimes Germanic mythology to Christianity and show them to be one and the same system. Such were Othmar Frank’s Das Licht vom Orient (1808), Johann Arnold Kanne’s Erste Urkunden der Geschichte oder allgemeine Mythologie (1808), Joseph G6rres’ Mythengeschichte der asiatischen Welt (1810) and Friedrich Creuzer’s Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Vdlker (1810-12). These books, which relied on an extensive use of etymologies, drew on a tradition that went back to the seventeenth century’1 but they made reference to the more reliable information gathered by British Sanskritists in Calcutta, although unlike Schlegel, those authors did not have direct access to Sanskrit sources. The growing interest in the Orient was also reflected by the establishment of journals dedicated to information on Asian cultures. Such were Julius Klaproth’s Asiatisches Magazin, which appeared in Weimar in 1802, and the Fundgru- ben des Orients, established by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall in Munich in 1807.

6 John Zephaniah Holwell, Interesting historical events, relative to the provinces of Bengal, and the empire of Indostan. With a seasonable hint and perswasive to the honourable the court of directors of the East India Company. As also the mythology and cosmogony, fasts and festivals of the Gentoo’s, followers of the Shastah. And a dissertation on the metempsychosis, commonly, though erroneously, called the Pythagorean doctrine, 3 vols. (London: Becket and De Hondt, 1765-71).

7 A. Leslie Willson, A Mythical Image: The Idea of India in German Romanticism (Dur-

ham: Duke University Press, 1964), 24.

8 Thomas Trautmann, Aryans and British India (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1997), 72.

9 Thomas Maurice, Indian antiquities, 7 vols. (London: Elmsley, Richardson, 1793-

1800).

10 Friedrich Leopold Stolberg, Geschichte der Religion Jesu Christi, 15 vols. (Hamburg:

Perthes, 1806-18).

“The brothers Schlegel, who asked themselves what was the essence of German and European culture, what were its sources, and what was the historical model it should look to, began seeking the answer in India.”

The publication of Jones’ translation of Kalidasa’s Shakuntala in 1789,12 rendered into German by Georg Forster in 1791,'” was received with great enthusiasm by many German intellectuals, including Herder, Goethe, and Schiller. For Herder, India represented the childhood of humanity, an age of innocence, religiosity and closeness to nature, all of them features that later became prominent in the image the Romantics had of India.14 For the Early Romantics, India was a promising source for literary and cultural regeneration. Thinkers such as Novalis saw it as a counter-image to Enlightened and rationalist Europe.’5 As early German nationalism developed, so grew the attraction of an alternative course of the history of civilization to that beginning with Greece and Rome. German intellectuals such as the brothers Schlegel, who asked themselves what was the essence of German and European culture, what were its sources, and what was the historical model it should look to, began seeking the answer in India. At the same time, while looking for cultural inspiration in ancient India, they shared with the British Orientalists in Calcutta the feeling of superiority over contemporary Indians. While in England this brought the decline of the appreciation of Hindu civilization, most effectively through the Utilitarian criticism of James Mill and the Evangelist criticism of Charles Grant,16 in Germany admirers of India almost exclusively concentrated upon ancient India, with the rare exception of the Halle historian Matthias Christian Sprengel who studied the political history of contemporary India.17

11 Frank Manuel, The Eighteenth Century Confronts the Gods (Cambridge, Mass.: Har-

vard University Press, 1959), 115.

12 Kalidasa, Sacontala or, The fatal ring: an Indian drama, trans. William Jones (Calcutta,

1789).

13 Kalidasa, Sakontala, oder, Der entscheidende Ring: ein indisches Schauspiel, trans.

Georg Forster (Leipzig and Mainz: Fischer, 1791).

14 Willson, Mythical Image, 53.

1′ Wilhelm Halbfass, India and Europe (Albany: State University of New York Press,

1988), 74.

16 Trautmann, Aryans and British India, 99

Raymond Schwab, as the title of his classical book The Oriental Renaissance implies,18 viewed the Renaissance as an appropriate metaphor for the nineteenth-century awakening of European fascination with India. But in the context of Schlegel’s book, the comparison of Indian studies with the classical studies of the Renaissance raises many questions. Here I intend to concentrate upon how this comparison reflects the way Schlegel viewed the relationship between Europe and India. While the earlier Renaissance had remained within the limits of Europe, a major significance of the call for exploring Indian civilization was that Europe was to transcend its borders.

My main question will be: did Schlegel view his Oriental Renaissance as something that, like the earlier Renaissance, meant exploring a culture that was actually a part of European civilization, or did he see it as a way to expand the scope of European civilization to other civilizations? Did he have a notion of a universal community of cultures, of which both Europe and India were members?

These questions are related to the discourse that developed following the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism.19 I agree with Dorothy Figueira’s criticism of Said’s attempt to view the European attitude to the Orient as driven by a patronizing will to rule.20 According to Figueira, “the Romantic writers appropriate the Other for their own purposes, but they also rethink the Self through the Other so as to expand their own cultural boundaries and those of their society. At the same time, in trying to understand the Other, they also appropriate it and colonize it, or at least create the conditions for the colonization.” However, she makes a distinction between this combination of knowledge and power and that presented by Said.21 Schlegel’s treatment of India falls within this definition of the romantic attitude to the Orient. Schlegel was trying to understand Europe through India. He was trying to bring India and Europe together and at the same time to keep them apart. However, in her chapter on Schlegel, in rightly defending Schlegel from the charges of colonialism, racism, and anti-Semitism, Figueira underestimates the political stance that did exist in Schlegel’s book.22

17 Dietmar Rothermund, The German Intellectual Quest for India (New Delhi: Manohar,

1986), 22-24.

18 Raymond Schwab, The Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s discovery of India and the East

1680-1880, trans. Gene Peterson-Black and Victor Reinking (New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press, 1984).

19 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978).

20 Dorothy M. Figueira, The Exotic: A Decadent Quest, (Albany: State University of New

York Press, 1994), 3.

21 Figueira, The Exotic, 12-13.

German Orientalism posits a special problem for postcolonial criticism considering the importance of a tradition of scholarship of the Orient that was produced by a country with few direct colonial interests in the area. The discrepancy encourages a search for a wider definition of the political function of Orientalism that would include not only the construction of a colonial empire in the Orient. In the German case, this should include the construction of national identity and national visions.23 This is especially true for the case of German Indology. According to Sheldon Pollock, both the investment and the production of pre-1945 Germany in Indological research surpassed that of the rest of Europe and America combined. Pollock suggested the phrase ‘internal colonialism’ for understanding the way knowledge and power were linked in the construction and the production of German Indology.24 While this is certainly true when considering the role that Indology and linguistics played in the construction of the anti-Semitic

idea of the ‘Aryan Race’ from the middle of the nineteenth century onward, for the earlier period it would be more correct to speak of a German search for national identity that was dominated by an obsession for linguistic origins.25 On another level, German Indology had an obvious colonial context in that it was born out of British colonial scholarship, from which it received not only information and texts but also its analytical concepts. The emphasis on sacred texts and on reconstructing a primordial India lost in time were central for the British Orientalist project of the eighteenth century, as was the concept of the “mystical” character of Indian religion. They originated from both the Christian framework within which Indian religions were perceived, and from the contribution of Indian informants, usually Brahmins, who served as the teachers of the Orientalists and had a clear interest in promoting a view of Indian religions and culture built upon the centrality of the texts that they possessed.26 Political interests of both colonizers and colonized shaped the form in which knowledge of India was represented in Europe, including Germany, where it was immediately used in a variety of internal and external political debates.27

22 Ibid., 57-60.

23 Jennifer Jenkins, “German Orientalism, Introduction,” Comparative Studies of South

Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24, 2 (2004): 97-100.

24 Sheldon Pollock, “Deep Orientalism? Notes on Sanskrit and Power Beyond the Raj,” in Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament, ed. Carol Breckenridge and Peter Vander Veer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 76-133.

25 Kveta Benes, German Linguistic Nationhood, 1806-1866: Philology, Cultural Translation, and Historical Identity in Preunification Germany (Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Washington, 2001), 4.7

For Schlegel, thinking about India could never be separated from thinking about Europe. It was no coincidence that the time when he began to be seriously engaged with Indian studies was also the time when he was developing his conception of Europe. This period began in spring 1802, when Schlegel came to Paris. There, Schlegel established and edited the periodical Europa that, according to Ernst Curtius, was designed to introduce German readers to the best productions of French culture.28 Schlegel also tried to introduce French intellectuals to the cultural achievements of the Germans. He lectured to French intellectuals on German language and literature and even planned to establish an academy of German literature in Paris that would form the basis for an international European university.29 Henry Chelin argues that Schlegel was far from advocating the German- French partnership that Curtius and Ernst Behler attribute to him. However, he too believes that the journal reflected Schlegel’s vision for Europe: a united continent under German leadership.30

Schlegel presented his European vision for the first time in the essay Reise nach Frankreich. The essay was published in the first volume of Europa and reveals the influence of Novalis’s Die Christenheit oder Europa. Novalis’s essay has been defined as the best example of romantic cosmopolitanism, using an ahistorical image of medieval Europe to represent the ideal of a universal spiritual community.3′ Schlegel, too, constructed Europe as the whole world on a small scale.32 Europe was for Schlegel more than a continent. It was a project of spiritual harmony.33 However, Schlegel’s thinking was more historical than that of Novalis.34 Like Novalis, Schlegel expressed in Reise nach Frankreich, for the first time in his writing, a longing for the lost harmony and poetical character of the Middle Ages. He mourned the failure of Emperor Charles V to achieve the union of Germany and Spain, which would have prevented the disastrous splitting of the continent between north and south.3″ For Schlegel, the distinction between North and South corresponded to the distinction between Romantic and Classic, Modern and Ancient, Christian and Greek.36

26 Richard King, Orientalism and Religion (London: Routledge, 1999), 102.

27 Ibid., 97.

28 Ernst Robert Curtius, “Friedrich Schlegel und Frankreich,” in Kritische Essays zur Eu-

ropiiischen Literatur, ed. Curtius (Bern: Francke, 1950), 86-99, here 90-91.

29 Ernst Behler, Friedrich Schlegel in Selbstzeugnisse und Bilddokumenten (Reinbek: Ro-

wohlt, 1966), 88.

30 Henri Chelin, Friedrich Schlegels Europa (Frankfurt am Main, Bern: Lang, 1981), 107.

3′ Pauline Kleingeld, “Six Varieties of Cosmopolitanism in Late Eighteenth-Century Ger-

many,” JHI 60 (1999): 505-24.

32 Schlegel, KA, 7: xliv.

33 Behler, Selbstzeugnisse, 89.

34 KA, 20: xxxiii.

While Schlegel was concerned about the split between North and South, he was also interested in Europe’s relationship with the East. Schlegel had held a vague notion of the romantic quality of the East, and especially India, since at least 1797, when he abandoned his admiration of Greek poetry as the sole standard for poetic style and began to develop his concept of romantic poetry. Like most Romantics, and many non-romantic writers, he admired Shakuntala. In his fragments, Schlegel praised the romantic nature of Indian poetry. He wrote that the novel and the comedy are the basic forms of Indian poetry,37 and also that “the most sublime novel is Indic.””3 Schlegel believed the romantic poetry of India could inspire European poetry. In 1800 he already expressed his hope that oriental poetry would be some day as available as Greek poetry. “In the orient,” he wrote in his Rede iiber die Mythologie, “we must look for the most sublime form of the Romantic, and only when we can draw from the source, perhaps then will the semblance of southern passion, which we now find so charming in Spanish poetry, once again appear to us as occidental and sparse.39

However, it was only after his arrival in Paris that Schlegel became actively interested in the study of Indian civilization. This interest was closely connected to his hope of revitalizing European religion. In 1798 Schlegel already declared in a letter to Novalis his intention to establish a new religion that would be more mystical than Christianity.40 In his 1800 Rede liber die Mythologie he pointed to Europe’s need for a new mythology that would serve as the focus for literature, just as the old mythology had done for Greek and Roman literature.41 In his notebooks from the Athenium years he hinted at India, Iran, Egypt and the Germanic world as possible sources of inspiration for such a mythology.42

35 KA, 7: 62.

36 Heinz Gollwitzer, Europabild und Europagedanke: Beitrdge zur deutschen Geistesge-

schichte des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts (Munich: Beck, 1951), 160.

37 KA, 16: 322.

38 Ibid., 354.

39 “Im Orient mtissen wir das h6chste Romantische suchen, und wenn wir erst aus der

Quelle sch6pfen kdnnen, so wird uns vielleicht der Anschein von stidlicher Glut, der

uns jetzt in der spanischen Poesie so reizend ist, wieder nur abendlandisch und sparsam

erscheinen.” KA, 2: 320 (translation corrected); Schlegel, Dialogue on Poetry, trans. Ernst

Behler and Roman Struc (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1968), 87.

40 KA, 24: 204-208.

“Asia was the opposite of Europe: it was unified, whereas Europe was fragmented; it was religious, whereas Europe was secular”

In Reise nach Frankreich Schlegel expressed his belief that only Asia could cure Europe from its tendency towards fragmentation.43 Schlegel believed the political unification of Europe could only be a part of a spiritual revolution that would make Europe a harmonious spiritual community. India should be the source of this spiritual revolution: “One would advise anyone who wishes to see religion to travel to India for this purpose, just as one would go to Italy to study art. In India, he can be sure to find at least fragments of that which in Europe he would certainly seek in vain.”44 He also believed India was the source of all the spiritual tendencies of Europe.4s Thus, the study of Indian literature for Schlegel involved both going out of and staying within European civilization. Asia was the opposite of Europe: it was unified, whereas Europe was fragmented; it was religious, whereas Europe was secular. But at the same time Asia was the source from which Europe came.

Schlegel’s idealized projections of the sharp difference between Europe and Asia in terms of unity and fragmentation were not unique. Enlightenment thinkers stressed the uniformity of Asian social and political systems. According to Montesquieu’s doctrine of Oriental despotism, Asia had always been characterized by much greater political unity than Europe, and Asian societies had remained unchanged through time.46 Voltaire opposed Montesquieu’s theory of Oriental despotism.47 He argued that the Mughal emperor did not stand above the law.48 Of Chinese government he said: “I know from the unanimous reports from our missionaries of various sects, that China is governed by laws, and not by a single arbitrary will.”49 However, just because its administration is based on law, it enjoys a high degree

of uniformity. Voltaire also adhered to the image of the unchanging nature of Asian civilizations. He wrote of “the rites of the ancient Bramins (sic), which are still preserved.”‘ The uniformity and stability of Asian countries to which these Enlightenment authors were referred were primarily social and political. They were far from the total harmony of spirit Schlegel was talking about. But the Enlightenment image of massive, uniform, unchanging Asian societies helped the Romantic thinkers build their own image of Asia.

41 KA, 2: 312.

42 KA, 16: 349.

43 KA, 7: 76.

44 “… man m6chte demjenigen, der Religion sehen will, raten, er solle, wie man nach

Italien geht um die Kunst zu lernen, eben so zu seinem Zwecke nach Indien fahren, wo er

gewif3 sein darf, wenigstens noch Bruchstiicke von dem zu finden, wonach er sich in

Europa zuverlissig vergeblich umsehen wiirde.” Ibid., 74.

45 Ibid.

46 Charles Louis de Secondat de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, trans. Thomas

Nugent (New York: Hafner, 1949), 224.

47 Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (London: NLB, 1974), 465.

48 S. N. Mukherjee, Sir William Jones: A Study in Eighteenth-Century British Attitudes to

India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 14-15.

49 Voltaire, Political Writings, ed. and trans. David Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 97.

Schlegel used geographical directions such as North and South, East and West as moral and cultural terms. According to Ernst Behler, Reisenach Frankreich may have marked the point in the history of literature where the myth of the East became a dominant theme in the Romantic historical thinking.51 But not only the East. While “the Orient” had been a common name for Asian cultures for a long time, “the West” as a name for European civilization was much less widespread. Montesquieu often referred to the differences between northern and southern peoples and wrote of “Oriental peoples,” but Europe was for him only “Europe,” not “the West.” According to Heinz Gollwitzer, around 1500 ‘Europe’ replaced ‘the Occident’ as the usual term for the civilization that developed in what used to be the western part of the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, the Orient of this Occident included not only the Islamic world but also the Byzantine Empire.52 According to Gollwitzer, the German word ‘Abendland’ had only a purely geographical meaning until the turn of the eighteenth century. He says Friedrich Schlegel was among the first intellectuals

who gave it a cultural meaning.53

Schlegel combined East and West with the terms South and North. For Schlegel, combining all these terms had the advantage of making it possible to link Europe with Asia. North and South, East and West were for him denominations of a common totality, and Schlegel could point to the affinity between North and East. In September 1802 Schlegel wrote to Ludwig Tieck: “How about your Nordic studies? I am becoming more and more convinced that the North and the Orient are the good elements of the world in every respect, in moral and historical regard-that for once all should

become the Orient and the North.”54

50 Voltaire, The Philosophy of History (New York: Philosophical Library, 1965), 77.

51 KA, 7: xliii.

52 Gollwitzer, “Zur Wortgeschichte und Sinndeutung von ‘Europa’,” Saeculum 2 (1951):

161-172.

53 Gollwitzer, Europagedanke, 14

“Sanskrit was “the source of all languages”

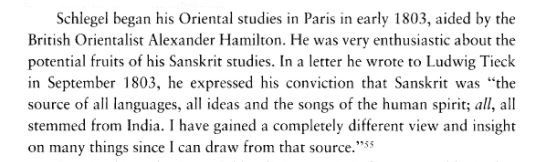

Schlegel began his Oriental studies in Paris in early 1803, aided by the British Orientalist Alexander Hamilton. He was very enthusiastic about the potential fruits of his Sanskrit studies. In a letter he wrote to Ludwig Tieck in September 1803, he expressed his conviction that Sanskrit was “the source of all languages, all ideas and the songs of the human spirit; all, all stemmed from India. I have gained a completely different view and insight on many things since I can draw from that source.””55

Despite this enthusiasm, Schlegel’s interest in India remained limited to what seemed to serve his broader theological, philosophical, literary and political fields of interest. It was significant that Schlegel showed no inclination to go to India physically, only intellectually. Further, he believed Ger- man scholars sitting in Europe could do a better job of translating Sanskrit works than the British Sanskritists in Calcutta.56 His attitude was common

to many German scholars and intellectuals. It brings to mind Johann Winckelmann, who introduced Greek art to the Germans and to Europe as a whole, but throughout a life devoted to everything Greek, never actually went to Greece itself.57 Winckelmann’s Greece was in Italy-as was Goethe’s,58 just as Schlegel’s India was in Paris. The comparison shows that Schlegel’s idealization of India was much more extreme even than Winckelmann’s idealization of Greece. Unlike Winckelmann, Schlegel had almost no visual evidence of the world he was trying to recreate, and he did not

feel he was lacking such evidence. He believed literary sources were enough, and even those were very limited. The exclusive focus on ancient literary sources meant that modern India was totally absent from Schlegel’s thought

and indeed he remarked several times on the non-consequence of modern India.59

54 “Was machen Deine nordische Studien?-Ich uiberzeuge mich immer mehr, dag der

Norden und der Orient in jeder Hinsicht, in moralischer und historischer Rucksicht die

guten Elemente der Erde sind-dagt einst alles Orient und Norden werden mug.” Ludwig

Tieck und die Briider Schlegel: Briefe, ed. Edgar Lohner (Munich: Winkler, 1972), 113.

5″ , … die Quelle aller Sprachen, aller Gedanken, und Gedichte des menschlichen Geistes;

alles, alles stammt aus Indien ohne Ausnahme. Ich habe tiber vieles eine ganz andere

Ansicht und Einsicht bekommen, seit ich aus dieser Quelle sch6pfen kann.” Lohner,

135-36.

56 KA, 2: 319.

57 Walter Rehm, Griechentum und Goethezeit: Geschichte eines Glaubens (Bern, Munich:

Francke, 1968), 6.

58 Rehm, Griechentum und Goethezeit, 141.

59 KA, 14: 26.

In his youth Schlegel wished to accomplish for Greek poetry what Winckelmann did for Greek art.60 Ernst Behler phrased this project of the young Schlegel as an attempt to become “the Winckelmann of Greek poetry.”6′ When he began his Indian studies, it appears he hoped to become what might be called ‘the Winckelmann of India.’ He hoped to be the one to show the Germans the benefits that the study of Indian literature could provide for their national Bildung. Like Winckelmann, he hoped to provide German culture with the inspiration of a civilization in which man lived in harmony with nature. The features that Schlegel sought in Indian literature-peace, harmony, totality, and attachment to nature-were very similar to those Winckelmann admired in Greek art. Schlegel himself believed in his youth that Greek literature was the ultimate model for European literature. He turned away from this exclusive admiration of Greek literature after 1796. Following Schiller’s influence, he could no longer accept Winckelmann’s call for the imitation of Greek art on German soil. Indian literature offered a good source of inspiration for Schlegel and other Romantics just because it was so little known-and therefore could not be imitated.

India had another important advantage over Greece for Schlegel in that its civilization was perceived to be essentially religious. In the Athendum fragments he increasingly stressed the mystical nature of Indian literature as opposed to the secularism and rationality of the Greeks. For Winckelmann and Goethe, Greece represented a natural and aesthetic civilization that could serve as an alternative to the dominant Enlightenment culture, whose center was Paris and whose historical model was Rome.62 Schlegel, a generation younger, was looking for a more spiritual alternative in India.

The idealized image of India formed a vital part of Schlegel’s critique of modernity. The unity and harmony which he believed he saw in India was what he thought was the most urgent need of the moderns. This need for harmony stood at the center of his thought since his youth. It points to his critical view of modernity even during his “progressive years” in the 1790s, before he began his shift to conservatism. His concept of Romantic poetry was built upon the need to make poetry harmonious with life. His call for a new mythology was meant to provide modern poetry with a focus around which it could be united. It was because fragmentation was such a distinctive feature of modern life that unity and harmony were so important to Schlegel.63 This helps to explain Schlegel’s attitude to modern India. Because India was for him the antithesis of modernity, modern India was of no interest to him. He did not believe India was immune to the general process of the degeneration of civilization, to which European civilization

was subject. On the contrary, he believed a new Europe, revitalized through the knowledge of ancient India, could bring new life to Asia.

60 Rehm, Griechentum und Goethezeit, 255.

61 Behler, Selbstzeugnisse, 29.

62 Rehm, Griechentum und Goethezeit, 24.

“What he thought of the city (Paris) outside the library drove him to the

Indian study no less than the manuscripts he found inside.”

The relationship between Schlegel’s critique of modernity and his idealized image of India was especially significant during his life in Paris. The literary sources he found there and the acquaintance with Alexander Hamilton were the external conditions that made it possible for Schlegel to become engaged in his Indian study. But it is significant that Schlegel devoted so much energy to this engagement precisely during his stay in the capital of modernity, as Paris was for him.64 Schlegel complained that he could found in Paris “no fantasy, no art, no love, no religion.” 65 He attributed this not to the national character of the French but to the degeneration of Europe as a whole, which he thought was stronger in Paris than in Germany.66 What he thought of the city outside the library drove him to the

Indian study no less than the manuscripts he found inside. When we add to this other features of Schlegel’s life in Paris: the study of medieval manuscripts, the preoccupation with old art, his social seclusion from French

people, his growing Catholicism, we can see the correlation between his reluctance to become involved with modern Paris and his interest in ancient India-and lack of interest in modern India.

Indeed Schlegel did not move from admiration of Greek poetry to a total condemnation of it. In the lectures on the history of European literature that he delivered to a small audience at his home in Paris in winter 1803-4, Schlegel presented Greek poetry as the origin of all European poetry.67 Of the Romans he wrote in 1800 that, like the French, “both nations were only evidence that there can be great nations without poetry, in spite of all effort and conceit.”68 It was indeed a common strategy among eighteenth-century German intellectuals to oppose Roman-French “Staats-

nation” to Greek-German “Kulturnation.”69 However, in these lectures Schlegel did criticize the polytheistic nature of Greek poetry that was rooted in its mythological origins. Greek mythology was pure polytheism, he said, without a trace of monotheism. In this respect, he believed that Greek mythology stood in striking contrast to Indian mythology, which was governed by the concept of the infinite and even showed knowledge of the Trinity.70

63 Hans-Christof Kraus, “Die Jenaer FrAihromantik und ihre Kritik der Moderne,” Zeit-

schrift far Religions- und Geistesgeschichte 47 (1995): 205-30.

64 Ingrid Oesterle, “Paris-das moderne Rom?” in Rom-Paris-London. Erfahrung und

Selbsterfahrung deutscher Schriftsteller und Kfinstler in den fremden Metropolen, ed.

Conrad Wiedemann (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1988), 375-419.

65 ” … keine Fantasie, keine Kunst, keine Liebe, keine Religion.” Georg Hirzel, “Unge-

druckte Breife an Georg Andreas Reimer,” Deutsche Revue fiber das gesamte nationale

Leben der Gegenwart, 18, IV (1893): 100.

66 KA, 7: 71-72.

67 KA, 11: 126.

68 “Beide Nationen nur ein Beweigi, dat es grotfe Nationen geben kann ohne Poesie, trotz

aller Miihe und Einbildung.” KA, 16: 322.

Somewhat less confidently, Schlegel presented the view that European civilization had originated in India. He did not say that this was the case; just that it was a well-founded assumption.71 This caution resulted from his emphasis in these lectures on the distinct nature of European literature. He sought to present all European literatures as belonging to a common civilization. He believed the distinctive character of this civilization was its diversity, but now he described this diversity in positive rather than negative terms. He claimed European literature was completely different from Asian literature and reached a higher degree of perfection due to Europe’s position and climate.72 In the manner of Montesquieu he said it was Europe’s fragmentation that contributed most to its cultural richness: “In Asia we usually see only great nations and monarchies that have almost no connection with foreign countries. In Europe we see from ancient times many smaller states that are divided and connected among themselves in the most diversified manner. This diversity of contacts and separations naturally had to bring great cultural diversity.”73 Here the fragmentation of Europe was not a fault to be cured by learning from Asia. Rather, it was something that distinguished European from Asian literature from the very beginning. In this sense, it was the contrast between European and Asian literature that gave Europe its distinctive quality.

69 Conrad Wiedemann, “Rom, Athen und die germanischen Wailder. Ein vergleichender

Versuch iiber nationale Ursprungsmythen der deutschen Aufklirung,” in Searching for

Common Ground: Diskurse zur deutschen Identitit 1750-1871, ed. Nicholas Vazsonyi

(K61n: B6hlau, 2000) 195-207.

70 KA, 11: 25.

71 Ibid., 15.

72 Ibid.

73 “In Asien treffen wir meistens nur grotie Nationen und Monarchien, die mit auswdirti-

gen Laindern beinahe in gar keiner Verbindung stehen. In Europa treffen wir schon in

ilteren Zeiten eine Menge kleiner Staaten an, die, wie schon gesagt, unter sich wieder auf

das mannigfaltigste geteilt und verbunden sind. Diese Mannigfaltigkeit von Trennungen

und Verbindungen mutate nattirlich eine ebenso grole Mannigfaltigkeit in der Bildung

hervorbringen.” Ibid., 16-17

“Reason, which caused the original error of this universal tradition, brought the further degeneration of European philosophy as well, until it became centered on utility and rationalism.”

The time between 1802 and 1808 was a transitional period in Schlegel’s life. During this time, the liberal, cosmopolitan literary critic, with pantheist sympathies, became a conservative, patriotic, Catholic theologian, philosopher, and historian, who was to join the service of Metternich as a writer of Austrian propaganda and as a member of the Austrian delegation to the Congress of Vienna and to the Diet of Frankfurt. Already in April 1804, just before he left Paris for Cologne, Schlegel wrote to his brother about his growing unhappiness in Paris, which he explained by his hostility to Napoleon and by his sympathy for Catholicism.74 In April 1808 Schlegel converted to Catholicism together with his wife Dorothea and a few months later he left Cologne for Vienna. The turn to Catholicism and conservatism affected Schlegel’s treatment of India in two ways. First, he no longer sought spiritual inspiration in India. Rather, he tried to find evidence for the truth of Christianity in Indian mythology. Second, Schlegel pointed to a direct connection between India and the Germanic part of Europe The religious change was manifested in the second part of Uber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier. Here Schlegel presented his doctrine of the degeneration of Indian thought from the Original Revelation towards a philosophy based on reason. Schlegel divided Indian philosophy into four schools, beginning with the doctrine of emanation, according to which all

phenomena are manifestaions of Divinity, followed by the materialist cult of nature, then dualism, and finally pantheism. He believed these schools represented a continuous degeneration. This degeneration began with the

system of emanation, which he said was the first system to replace the pure light of truth. It arose from the distortion of the original revelation by reason, which was incapable of understanding the divine message.75 The errors grew worse with the materialist cult of nature that had developed out of it.76 The degeneration culminated with pantheism, which was the first system based purely on reason: “All the other Oriental doctrines are founded

on divine wisdom and revelation, as much as they are clouded in legend and error. Pantheism is the system of pure reason.”77 Schlegel believed that these doctrines were common to all Oriental civilizations. They had developed out of the system of emanation.78 Pantheism represented the last phase of Oriental philosophy and the passage to European philosophy.79 Reason, which caused the original error of this universal tradition, brought the further degeneration of European philosophy as well, until it became centered on utility and rationalism.

74 Krisenjahre der Fraihromantik: Briefe aus dem Schlegelkreis, ed. Joseph K6rner (Bern,

Munich: Francke, 1969), 1: 74.

75 KA, 8: 207.

76 Ibid., 219.

77 “Alle andre orientalische Lehrbegriffe griinden und berufen sich noch auf g6ttliche

Wunder und Offenbarung, so entstellt auch alles durch Fabel und Irrtum sein mag. Der

Pantheismus ist das System der reinen Vernunft.” Ibid., 243.

78 Ibid., 1997.

“Schlegel believed all of these languages belonged to one family, with Sanskrit being the oldest of the group and the one from which the others grew.”

The religious motivation for the study of Indian mythology ceased to be the reconstruction of the Indians’ ancient spirituality. Schlegel’s main concern with the Indian study now was to present an argument against the

belief in moral and spiritual progress. So Schlegel’s doctrine was in fact a critique of modern rationalism and skepticism, calling for a return to reliance upon the Word of the Scriptures. According to Ernst Behler, it represented a critique of philosophical pantheism as it was represented by Schelling and of Schlegel’s own philosophical past as a radical thinker and a sympathizer of Pantheism.”8

At first sight, this is a doctrine that eliminated the opposition between Europe and Asia. Philosophy in Asia and Europe was merely one chain of continuous degeneration. The difference between the two was only relative: European philosophy was more degenerated than Oriental philosophy simply because it was younger, but the same principle of gradual degeneration ruled in both. This unity was supported by the affinity between Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and German. Schlegel believed all of these languages belonged to one family, with Sanskrit being the oldest of the group and the one from which the others grew.82

Schlegel described India as the origin of the oldest Oriental doctrine, the system of emanation and metempsychosis.83 He believed this system later spread not only to Greece through Egypt or west Asia but also as far as the Celtic Druids and the far north.84 The second system he mentioned, the cult of nature, was even more widespread and could be found with the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, the Germans, the Armenians, the Arabs, the

Greeks and the Romans.8″ According to Schlegel, the system of dualism was found not only in India and Iran but could also explain many Roman, Greek and Nordic legends.86 Pantheism, the youngest Oriental system, could be found in China, India and Iran.87 The spread of ancient mythology from India to other countries was not confined to those with a linguistic connection to India.

79 Ibid., 243.

80 Ibid., 193.

8′ Ernst Behler, “Das Indienbild der deutschen Romantik,” Germanisch-Romanische Mo-

natsschrift 49 (1968): 21-37.

82 KA, 8: 115.

83 Ibid., 199.

84 Ibid., 215.

85 Ibid., 223.

86 Ibid., 235

87 Ibid., 247.

Europe had an interesting position in Schlegel’s historical scheme. On one hand, ancient European nations shared the ancient mythology that Schlegel called ‘Oriental’. He said his general description of this mythology “can explain the European legends and the poetry of the mythologies of the Celts, the Romans, the Greeks, the Germans and the Slavs.””88 However, when Schlegel said pantheism represented the passage from Oriental to European philosophy he indicated something else by the attribute “European”-not a geographic expression but a phase in history. He meant that the European era of history was fundamentally different from the Oriental one. The European era was different in that it marked the beginning of a philosophy based on pure reason, which replaced the philosophy based on the Revelation. To this we can add his remark that under pantheism, mythology could only remain as an allegory.89 European thought was characterized by the lack of mythology-a reminder of his 1800 claim that Eu-

rope needed a new mythology.

In comparing the study of India with the study of classical antiquity during the Renaissance, Schlegel was calling on scholars to adopt the methods of that comprehensive study. He hoped to reinitiate the thorough study of antiquity that he believed had “deteriorated into futile scholarship.”90 Like scholars of the Renaissance who had rediscovered the historical chain that linked their own culture with that of ancient Greece, so the explorers of India would unveil the true origin of European civilization. The new study of India would not be merely an extension of the older Renaissance. It would also bring a reversal, or at least a correction of the outcome of the exaggerated preoccupation with Greece. Schlegel warned that “a too one-sided occupation with Greece drove the spirit too far away from the origin of all sublime wisdom. A new knowledge of oriental antiquity would bring us back to knowing the divine and to that noble power that gave life to all arts and knowledge.””91 He believed that such knowledge of the divinity and

nobility of the arts and sciences had existed during the Middle Ages. In his lectures on universal history in Cologne in 1805-1806, Schlegel said that the Middle Ages surpassed in morality and politics any other period in history.92 We cannot ignore, he said, the resemblance between the division of European society into estates and the division into castes in India. He added that the religious constitution of the Middle Ages could be compared to the finest institutions of the Orient, especially the Indians and the Egyptians.93 He considered the goal of politics to be bringing back the constitution of the Middle Ages and making it perfect.94

88 ” … man betrachte nach derselben Ansicht auch die europiischen Sagen und Dich-

tungen der keltischen, r6mischen, griechischen, germanischen und slavischen Mytholo-

gien.” Ibid., 261.

89 Ibid., 259.

90… zu einer in der Tat sehr schalen und unfruchtbaren Buchstabengelehrsamkeit her-

abgesunken.” Ibid., 30

“The Renaissance did not prevent the continuous decline of philosophy. The fault lied with the Reformation and the events following it that destroyed the unity of Europe”

Schlegel did not say that the Renaissance had put an end to the Middle Ages. This was rather the result of the Reformation that broke up the European commonwealth of the Middle Ages. However, he did say that the close

connection the Italians had always had to antiquity had negative political consequences because of their attempt to revive the ancient republics.95 The Renaissance had a deeper impact on European culture than on its politics. The enthusiasm for writing in Latin damaged the national literatures of Italy and Germany.96 Schlegel believed Europe’s encounter with ancient knowledge during the Renaissance did not prevent the continuous decline of philosophy. The fault lied with the Reformation and the events following it that destroyed the unity of Europe.97 Schlegel was hoping for a new spiritual revolution that would undo the evils of the Reformation and reunite Europe under one confession, a new, Oriental Renaissance that would make right the excesses of the old Renaissance.

Avoiding the excesses of classical studies also meant reorganizing the cultural hierarchy among European nations. An important contribution of Indian studies, for Schlegel, was to sever the old scheme according to which European civilization was the daughter of classical antiquity. By 1805 Schlegel transferred the center of medieval culture from northern France to Germany. He believed now that romantic poetry had originated from the poetry of the ancient Germanic tribes. Its spirit was the spirit of Germanic mythology.98 The Germanic tribes, he argued, were not the brutal barbarians who destroyed the civilization of the Roman Empire, as they were described in French history books.99 Rather, they were free people who were oppressed by the despotic Romans.100 They had a developed civilization of their own. They had cities, kingdoms, trade, a literature and a good constitution, from which feudalism developed.h11 Their civilization was the basis on which the culture of the Middle Ages was built. But what was the

basis of the civilization of the ancient Germanic tribes? Here Schlegel assigned a special role to India. The Germanic mythology that was the basis for the romantic spirit of the Middle Ages was part of the ancient mythology that had a share in the Original Revelation and had its origin in India.

91 “Und wenn eine zu einseitige und blof3 spielende Beschaftigung mit den Griechen den

Geist in den letzten Jahrhunderten zu sehr von dem alten Ernst oder gar von der Quelle

aller h6hern Wahrheit entfernt hat, so diirfte diese ganz neue Kenntnis und Anschauung

des orientalischen Altertums, je tiefer wir darin eindringen, um so mehr zu der Erkenntnis

des G6ttlichen und zu iener Kraft der Gesinnung wieder zurickftihren, die aller Kunst

und allem Wissen erst Licht und Leben gibt.” Ibid., 317.

92 KA, 11: 166.

91 Ibid., 167.

94 Ibid., 256.

95 Ibid., 178.

96 KA, 6: 220.

97 KA, 6: 259-60.

Schlegel believed the Germans, Greeks, and Romans inherited their religious ideas and political organization from India. This political organization was based on the caste system of India. Schlegel was convinced that the division of European society into priests, a warring nobility, peasants, and artisans had originated in India.102 Unfortunately, while the Germans improved their ancient constitution-feudalism was better than the caste system-in Greece, the original constitution deteriorated into republic, anarchy, and tyranny.103

Schlegel here broke away from the image of the continuous chain of European civilization that stretched from Asia to Greece, from Greece to Rome, and from there to northern Europe. The metahistorical picture he painted was of a two branched path by which civilization had moved from Asia to Europe-one which went through Greece and Rome and another that went to northern Europe. In this way Schlegel reaffirmed European unity-the civilizations of north and south Europe did not come from different sources. He also gave the civilization of the north an important ad- vantage over the south-its civilization had remained truer to its sources.

These ideas were reflected in Uber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier. Indeed Schlegel believed all of the civilizations of the world had originated in India-but not all peoples were civilized. Among civilized nations, there was a difference in the way they received their civilization. Those who had a language that was related to Sanskrit, such as the Germans and the Greeks, had immigrated from India and brought their civilization from there. For Schlegel, these were ‘organic’ languages (in which the root was internally modified, and were considered superior) and derived from a divine origin. Those who had an unrelated language, which he called “mechanical” (that is, used particles that were external to the root and were regarded as inferior), such as the Egyptians, received their civilization in an indirect way, through colonies of Brahmins.104 Faced with the difficulty of explaining why the Germans emigrated from “the most fertile part of Asia to the furthest Skandinavian North,”1’s Schlegel said that “in the Indian mythology there is something that can explain this orientation to the north. This is the legend of the wonderful mountain Meru, where Kuvero, the god of richness, rules.”106 Another wave of Indian migration led to the foundation of the civilizations of Greece and Rome.107

98 KA, 7: 152.

99 KA, 14: 106.

100 Ibid., 104.

101 Ibid., 112-16.

102 Ibid., 28.

103 Ibid., 63.

The peoples who had migrated from India did not show the same truthfulness in keeping their ancient traditions. According to Schlegel, when Alexander the Great reached India, he found there great monarchies, with the power of the crown limited by the rights of the priesthood and the nobility. This was the kind of government for which Schlegel admired medieval Germany. However, the Greeks by this time could no longer comprehend this kind of estates-based (stdindische) constitution, and mistook it for a republican form of government.108 The Germans emerge from this description as the modern European nation with the most direct connection to the ancient Indian civilization. Schlegel could now claim that German culture was purer than French culture without being more primitive. Thus, far from presenting a unified world civilization, Schlegel actually presented a complex hierarchical framework. At the bottom were savage peoples with no connection to ancient civilization. Above them stood civilized peoples who did not originate in India, but received their civilization indirectly through priestly colonies. Still higher were all peoples with an “organic,” Sanskrit-related language, who had emigrated from India. These were mostly European peoples. Even among these, the Germans were the ones closest to the Indian source and the ones best fit to lead the others to a regeneration of the old spirit.

104 KA, 8: 279.

105 “. . . wie eine V1lkerschaft aus dem fruchtbarsten und gesegnetsten Erdstriche Asiens

bis in den iufgersten skandinavischen Norden hinauf habe wandern m6gen.” Ibid., 291.

106 “In der indischen Mythologie findet sich etwas, was diese Richtung nach Norden voll-

kommen erklaren kann; es ist die Sage von dem wunderbaren Berg Meru, wo Kuvero, der

Gott des Reichtums, thront.” Ibid., 291-93.

107 Ibid., 287.

10s Ibid., 289.

“In recent years, these ideas have been criticized for being at least potentially racist.”

In recent years, these ideas have been criticized for being at least potentially racist. Sebastiano Timpanaro characterizes Schlegel’s linguistic typology as “a construct that would exercise heavy influence on a great part of 19th-century ethnography, which, even when repudiated its Romantic and mystical spirit, would retain and develop its budding colonialist and racist inclinations.”109 [Author: I have added ‘it’ in Timpanaro’s passage. Please check the original.] Leon Poliakov writes that Schlegel gave the Germans a myth of an Aryan race, although he acknowledged Schlegel’s support for Jewish emancipation.110 Jeffery Librett interprets U(ber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier as an argument whose aim is the total absorbtion of a dead Judaism into a living Christianity.”1′ Manuel da Rocha Abreu recently linked Schlegel’s conception to the racist ideas of late eighteenth-century German anthropologists Samuel Soemerring and Christoph Meiners.”12 However, this view has its critics, such as Konrad Koerner”d and Tod Kontje,114 who warn against drawing a historical teleology from the Romantics to the Nazis.

“German nationalism was at its inception. Its development was related to the opposition to Napoleon.”

Schlegel’s view should be examined in the context of early German nationalism. During the first decade of the nineteenth century, German nationalism was at its inception. Its development was related to the opposition to Napoleon. This opposition could be either from the left or from the right. Accordingly there were progressive nationalist views, calling for the fulfillment of the ideas of the French Revolution through a unified German state, and conservative nationalist views, linked to the idea of Restoration. Conservative thinkers like Joseph Gorres and Adam Miiller shared Schlegel’s idealization of the political and spiritual conditions of the Middle Ages. They viewed the culture of the Middle Ages as an essentially German culture. They sought to restore “Ancient German Liberty,” which was synonymous with feudalism, and the “Christian Community,” which was necessarily unified under one Catholic confession. These two parts of the vision of political romanticists – the restoration of ancient German liberty and of the Christian community – were reflected in Schlegel’s views about India. He sought to show that these were the true origins of European civilization. Just as ancient mythology was actually a distorted offspring of the original revelation, so was the politics of the ancients a distorted form of the political institutions that were carried by the migrants from India. In this way Schlegel tried to present a counter-image to the political images of Napoleonic France that were based on the historical models of Greece and Rome.

109 Sebastiano Timpanaro, “Introduction,” Friedrich Schlegel, Uber die Sprache und die

Weisheit der Indier: ein Beitrag zur Begriindung der Altertumskunde, ed. E.F.K. Koerner

(Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1977), xxxviii.

10 Leon Poliakov, Der Arische Mythos: zu den Quellen von Rassismus und Antisemi-

tismus, trans. Margarete Venjakob (Hamburg: Junius, 1993), 217.

11 Jeffery Libbrett, “Figuralizing the Oriental, Literalizing the Jew: On the Attempted

Assimilation of the Letter to the Spirit in Friedrich Schlegel’s Uber die Sprache und Weis-

heit der Indier,” The German Quarterly 69 (Summer 1996) 260-76.

112 Manuel da Roch Abreu, “Die Schule des Vorurteils. Friedrich Schlegels Sprachver-

gleich und die zeitgenissische vergleichende Anatomie in Deutschland,” kultuRRevolu-

tion. Zeitschrift far angewandte Diskurstheorie, 45/46 (2003): 109-15.

13 E. F. K. Koerner, “Linguistics and Ideology in 19th and 20th Century Studies of Lan-

guage,” in Language and ideology, vol. 1: Theoretical and cognitive Approaches, ed. R.

Dirven et al. (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 2001), 253-76, here 259.

114 Todd Kontje, German Orientalisms (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004),

109.

While Schlegel modeled the study of India on the humanistic project of the Renaissance, what he in fact intended was a reversal of that project, which in his mind was a part of the process that put an end to the spiritual and creative temper of the Middle Ages. In order to do that he searched for the origins of Europe in a place that he viewed as fundamentally different from Europe. By showing that both the north and the south of Europe originated from India, he hoped to enhance the unity of all European nations-and make it a unity centered around the Germanic culture of the north rather than the Latin culture of the south. He tried to change the identity of Europe from one that focused on the Greek heritage to one that derived from an Oriental heritage, common to both the Germans and to the French. However, unlike the admirers of Greece, and unlike himself a few years earlier, he did not wish to bring the oriental heritage itself back to Europe. He only meant to teach the Europeans what they should focus upon from the cultural wealth that they already possessed: that is, Christianity, feudalism and medievalism.

University of Heidelberg.