The Conference of the Birds or Speech of the Birds (Persian: منطق الطیر, Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr, also known as مقامات الطیور Maqāmāt-uṭ-Ṭuyūr; 1177)[1] is a Persian poem by Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar, commonly known as Attar of Nishapur.

Abū Ḥamīd bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm (c. 1145 – c. 1221; Persian: ابو حامد بن ابوبکر ابراهیم), better known by his pen-names Farīd ud-Dīn (فرید الدین) and ʿAṭṭār of Nishapur (عطار نیشاپوری, Attar means apothecary), was a Persian[3][4][5] poet, theoretician of Sufism, and hagiographer from Nishapur who had an immense and lasting influence on Persian poetry and Sufism. He wrote a collection of lyrical poems and number of long poems in the philosophical tradition of Islamic mysticism, as well as a prose work with biographies and sayings of famous Muslim mystics. Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr [The Conference of the Birds] and Ilāhī-Nāma [The Book of Divine] are among his most famous works.

The title is taken directly from the Qur’an, 27:16, where Sulayman (Solomon) and Dāwūd (David) are said to have been taught the language, or speech, of the birds (manṭiq al-ṭayr). Attar’s death, as with his life, is subject to speculation. He is known to have lived and died a violent death in the massacre inflicted by Genghis Khan and the Mongol army on the city of Nishapur in 1221, when he was seventy years old.

In the poem, the birds of the world gather to decide who is to be their sovereign, as they have none. The hoopoe, the wisest of them all, suggests that they should find the legendary Simorgh. The hoopoe leads the birds, each of whom represents a human fault which prevents human kind from attaining enlightenment.

The hoopoe tells the birds that they have to cross seven valleys in order to reach the abode of Simorgh. These valleys are as follows:[3]

1. Valley of the Quest, where the Wayfarer begins by casting aside all dogma, belief, and unbelief.

2. Valley of Love, where reason is abandoned for the sake of love.

3. Valley of Knowledge, where worldly knowledge becomes utterly useless.

4. Valley of Detachment, where all desires and attachments to the world are given up. Here, what is assumed to be “reality” vanishes.

5. Valley of Unity, where the Wayfarer realizes that everything is connected and that the Beloved is beyond everything, including harmony, multiplicity, and eternity.

6. Valley of Wonderment, where, entranced by the beauty of the Beloved, the Wayfarer becomes perplexed and, steeped in awe, finds that he or she has never known or understood anything.

7. Valley of Poverty and Annihilation, where the self disappears into the universe and the Wayfarer becomes timeless, existing in both the past and the future.

Sholeh Wolpé writes, “When the birds hear the description of these valleys, they bow their heads in distress; some even die of fright right then and there. But despite their trepidations, they begin the great journey. On the way, many perish of thirst, heat or illness, while others fall prey to wild beasts, panic, and violence. Finally, only thirty birds make it to the abode of Simorgh. In the end, the birds learn that they themselves are the Simorgh; the name “Simorgh” in Persian means thirty (si) birds (morgh). They eventually come to understand that the majesty of that Beloved is like the sun that can be seen reflected in a mirror. Yet, whoever looks into that mirror will also behold his or her own image.”[3]:17–18

If Simorgh unveils its face to you, you will find

that all the birds, be they thirty or forty or more,

are but the shadows cast by that unveiling.

What shadow is ever separated from its maker?

Do you see?

The shadow and its maker are one and the same,

so get over surfaces and delve into mysteries.[3]

Commentary

Attar’s use of symbolism is a key, driving component of the poem. This handling of symbolisms and allusions can be seen reflected in these lines:

It was in China, late one moonless night,

The Simorgh first appeared to mortal sight-

Beside the symbolic use of the Simorgh, the allusion to China is also very significant. According to Idries Shah, China as used here, is not the geographical China, but the symbol of mystic experience, as inferred from the Hadith (declared weak by Ibn Adee, but still used symbolically by some Sufis): “Seek knowledge; even as far as China”.[5] There are many more examples of such subtle symbols and allusions throughout the Mantiq. Within the larger context of the story of the journey of the birds, Attar masterfully tells the reader many didactic short, sweet stories in captivating poetic style.

Sholeh Wolpé, in the foreword of her modern translation of this work writes:[3]

The parables in this book trigger memories deep within us all. The stories inhabit the imagination, and slowly over time, their wisdom trickles down into the heart. The process of absorption is unique to every individual, as is each person’s journey. We are the birds in the story. All of us have our own ideas and ideals, our own fears and anxieties, as we hold on to our own version of the truth. Like the birds of this story, we may take flight together, but the journey itself will be different for each of us. Attar tells us that truth is not static, and that we each tread a path according to our own capacity. It evolves as we evolve. Those who are trapped within their own dogma, clinging to hardened beliefs or faith, are deprived of the journey toward the unfathomable Divine, which Attar calls the Great Ocean.

Wolpé further writes: “The book is meant to be not only instructive but also entertaining.”

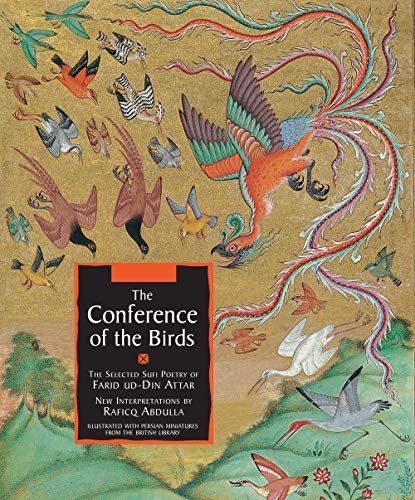

The Conference of the Birds