The following is excerpted from a talk given by the Vidyadhara at the 1974 Vajradhatu Seminary held at Snowmass Village, Colorado.

I thought we’d discuss the notion of tulkus. It is basically connected with the three kaya principle as well as the idea of the guru principle, yidams, et cetera. I think basically it is very simple. The enlightened state has three levels: the dharmakaya, which is the I ultimate being, the origin of everything, formless and all pervasive; the sambhogakaya, which is the manifestation of the activities of dharmakaya into the visible level of energy, play and everything; and the nirmanakaya, which represents the sense of actual earthly connections, energy materializing on a physical plane, particularly as human beings. The good intention extends towards all the rest of the realms as well, but in general the enlightened ones find that human beings are more workable. They speak language; they have developed intelligence; they have complicated social systems; and they also experience pain more acutely than any of the other realms which are dissolved much more into their own confusion and so are more freaked out than human beings. So the human realm is the most workable situation of all.

The Tibetan translation of nirmanakaya buddha is tulku; tul means “emanation,” and ku means “body,” so tulku means “emanated body.” In this context, for instance, Gautama Buddha is a tulku.

There are several types of tulkus. The buddha on earth is one type of tulku. The images of Buddha are also known as tulkus. “tulkus of art.” Another tulku is the tulku who continues to be reborn constantly in order to help beings on various levels.

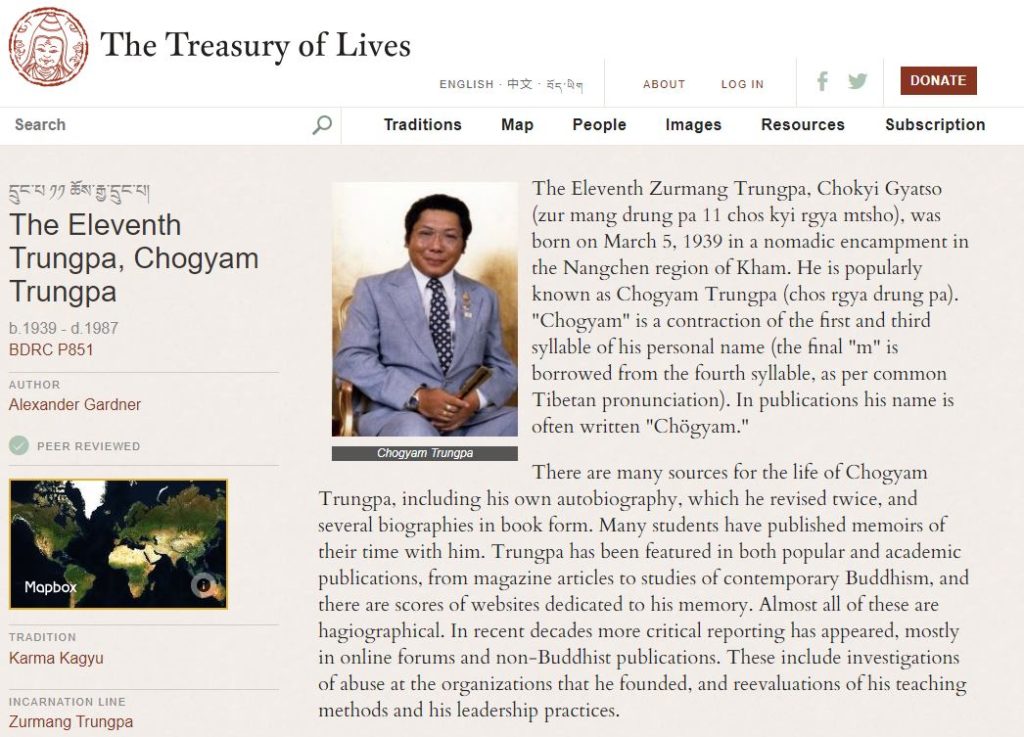

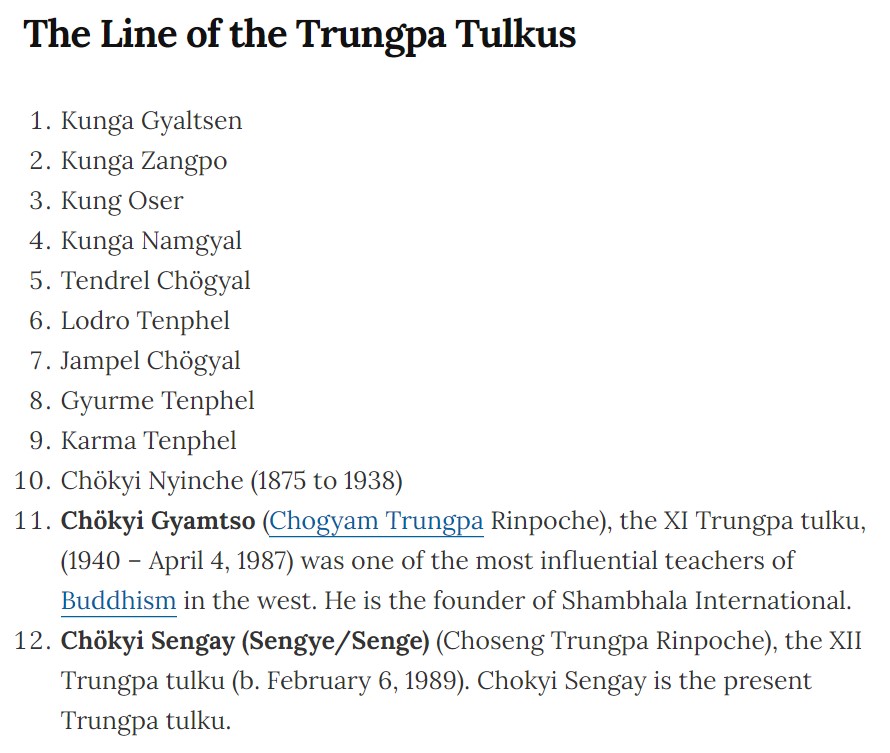

In connection with that I was thinking of discussing some of the Trungpas, who are notable as a whole lineage of incarnations. There are ten incarnated Trungpas. The first one is not an incarnation of Trungpa but Trungpa himself, which makes eleven Trungpas and ten incarnations.

The first Trungpa was one of the disciples of Trungmase, a siddha who was a disciple of the seventh Karmapa, Tesshin Shegpa. Trungmase was born in the far east of Tibet as a prince. Leaving his kingdom he became just a traveler. He renounced his kingdom. Then he arrived at Karmapa’s monastery and became a disciple of the seventh Karmapa. Karmapa sent him back to his home ground and told him to start anyplace where he could find a practicing place and teaching situation. So he came back to eastern Tibet and settled down. He practiced meditation there in a hut made out of reeds. He spent a long time there doing sitting meditation practice, something like six years, and he had very little to eat, but nobody discovered who he was. Eventually he began to feel that he was able to relate with students and that he was in a situation to do so. The story’ says that he decided to go back and ask his guru. But somehow he got a message—some merchants brought mail for him that said, “Don’t come back. Go ahead,” or something like that. He understood that to mean that he didn’t have to ask if he was okay to teach or not. So he realized the message. Then, having gotten the message, he came back to his hut again and began to teach. In particular he began to teach the six yogas of Naropa and the teachings connected with that—anuttara yoga. He was an expert on that and he gathered a large number of disciples. The local principalities also began to take an interest in his teachings and his being. He had already built that reed hut so he began to teach in that hut. Exentually he had eleven disciples. Eight of them were called the “eight realized ones,” and three of them were called “the three idiots.” [Laughter.] The first Trungpa was one of the three idiots.

The word trungpa is an honorific term, which literally means “attendant.” Ideally when somebody serves their guru twenty-four hours a day, they begin to get some glimpse of the workings of his mind. They begin to get messages and reminders of awareness and things like that. So the best way to develop is to be the guru’s servant. That’s the tradition. So trung means “close,” “nearby,” and pa makes that a noun, so trungpa means “he who is close to the teacher.” Trungpa is literally an honorific word for attendant.

The first Trungpa was born in the family of one of the local lords. He was educated and raised as an educated person. In his youth, his teens, he worked with his father ruling the country, collecting taxes and fighting with the hostile neighborhoods and everything. Then he left his kingdom, his principality. He had heard the name of Trungmase so he abandoned his home and settled with him. He spent a long time, something like twenty years, practicing meditation. And he received a lot of teachings at the beginning: the various levels of studying Cakrasamvaratantra; and various sadhanas; the external sadhana. the internal sadhana, the secret sadhana and so forth. He studied and practiced the six doctrines of Naropa and everything. And then his teacher sent the first Trungpa away. He said, “Now it is time for you to go away from me; you have received enough of what I have. You should find your own monastery, your own place to stay and to teach other people.”

So he visited various places. He traveled towards eastern Tibet and came to the fort of Atoshelubum, who was the local landowner and local lord. When the first Trungpa arrived, he was repeating tne sutra of Manjusri. In it there’s a particular phrase, chokyi jetsen legpan zug, which means “Firmly plant the banner of dharma.” So he arrived with that particular verse at the door of Atoshelubum’s castle. He was well received and he became a teacher of Atoshelubum, who offered his fort and his castle as a monastery. Without very much interest, the first Trungpa accepted, but then he just continued his travels.

The second Trungpa (there are very few stories about him) was also a traveler. After the first Trungpa’s death, the second Trungpa was discovered by Karmapa. as usually happens. The second Trungpa was discovered as an incarnation of the first Trungpa. But there was no monastery, no establishment. He just became a student of Trungmase, a student of a student of Trungmase by that time.

During the time of the third Trungpa something happened. The Trungpa incarnations organized a group of Surmang monasteries, which were not actually stationed in one place. They usually camped around. In fact it was called Surmang garchen tengpa. which means, “Surmang, the great camp.” The monks traveled in caravans; their libraries were on pack mules; the shrine was a large tent; the monks’ quarters were also tents; and the abbots’ quarters were tents as well. There were supposed to have been something like 140 people traveling around. They would set up encampments. They usually traveled among the different districts of eastern Tibet; they traveled great distances. The pattern of the culture was that you traveled in the highlands during the summer when the highlands were not too cold and you traveled in the lowlands in winter because the climate there was relatively reasonable. And they set up temporary monasteries in each place they camped. So the monks had their practices developing and the student newcomers could be instructed. And in many cases, students from the local locality began to join the camp; they wanted to become novices and they were accepted. So as they went on their camp became larger. That was the pattern in Tibet at the time. Tsurphu, the Karmapas’ monastery, was itself happening in that fashion. It was called “the great camp of Karmapa.” So in most of Tibet, the Tibetan monastic system was not in permanent dwelling places but in tents.

Finally, at the end of the life of the third Trungpa, one of the Karmapas (I don’t remember exactly which generation of Karmapas it was) had a sudden insight. He sent an invitation to the third Trungpa to come and visit him. So the third Trungpa took a journey to central Tibet, which usually takes about six months, and Karmapa told him that the prophesy of the mahasiddha Drombipa had come true: “It is you. You are the incarnation of Drombipa. And the prophecy goes like this. Drombipa lived in India. One evening at the end of his life he was drinking out of his skullcup and he finally decided to transplant his mahamudra teachings somewhere other than India. He said, ‘In ten lifetimes (or something like that) I’ll be going wherever my skullcup lands.’ And then he threw his skullcup into the air and the skullcup Hew across India and landed in Surmang, on a particular little mountain. So you should establish a permanent monastery here.” And the place where the skullcup landed happened to be the castle of Atoshelubum. Since then it has been called Dudtsi-til, dudtsi meaning “amrita” and til meaning “hill.” Apart from that story about how the third Trungpa received instructions to establish a permanent monastic residence, nothing very much is known about him.

The fourth Trungpa was very well known as a teacher throughout the Kagyu tradition. He was the only person who actually received what’s called the shije tradition of one of the contemplative schools of Tibetan Buddhism, that is, the teachings of cho [rnchod]. The basic philosophy of cho is that instead of asking for protection from the mahakalas or your guru, you give up your negativities and your security and ask the enemies or the demons, whoever they are, to consume you. That particular technique is very revealing to a lot of people, particularly in dealing with death and dealing with life, sickness and chaos. That particular practice is actually, something that the contemplative tradition extracted, so to speak from the prajhaparamita sutras. There is a touch of tantric outrageousness, stepping on your problems, stepping on your threat, as well. That particular practice is called cho and it usually takes place in the evening or at night. The fourth Trungpa made retreat centers, something like 108 retreat centers, supposedly in haunted places. And at the age of twenty-four he actually left his monastery. He bestowed the ruling of his monastery into his brother’s hands and he traveled around the country. He had a white yak without any horns, which is the most domesticated type of yak so that it wouldn’t be temperamental. And it had a ring through its nose so you could lead it wherever you wanted. He rejected any services from the monastery and decided to travel by himself. We used to have in our monastery the ring that went through his yak’s nose, a wooden loop. And he had a thighbone trumpet, which we also used to have in the treasury of the monastery. He used to call the haunting evil spirits to eat you up.

The fourth Trungpa was also one of the great teachers of the subsect of the Kagyupa tradition called the nendro [ngog?] Kagyu. That is one of the schools which is not included in the four great and the eight lesser schools. But it is another subsect which developed based on the idea of the pure land school. That particular sect is just like the pure land school in Japan; enormous emphasis is made on the worship of Amitabha and so forth.

So from that time onward the fourth Trungpa actually sat in a particular cave in Dudtsi-til. Just north of Dudtsi-til in a valley he found a cave, and he sat and meditated in it for six years. According to the story he fainted many times, but he regained consciousness and still continued to practice. He rejected any kind of hospitality from his monastery.

I think one of the outstanding aspects of the fourth Trungpa is that he was a great scholar. He wrote a three volume commentary on mahamudra, each volume probably having about a thousand pages in it. At that time nobody had ever written a commentary on mahamudra in the Kagyu lineage except for various manuals on visualization and other things. But this particular manual of mahamudra was straightforward; anything else like it had never been written. And according to the stories, one of the Karmapas was very shocked that the fourth Trungpa could say so many things about mahamudra, a three thousand page book. He said, “The fourth Trungpa’s skull must be bursting,” or “He must be just about to explode his skull if he has so much to say about mahamudra, if he has so much things to say about it.”

The rest of the Trungpas, apart from the eighth one are rather mellow and seem to be very ordinary, very domesticated people. The fifth Trungpa received an official title from the emperor of China. He was given seals and various official things, because that was the time of the Mongol invasion of Tibet. He was made into what’s called a hutoktu, which is a particular title of “royal imperial teacher” or “imperial guru.” or something like that. But apart from that, there isn’t very much known about him.

And I think the seventh Trungpa actually died very young. He was about eighteen years old when he died. When he was an infant his mother accidentally dropped him on the floor, which caused a concussion in his head. And that sickness continued throughout his life. But nevertheless he was supposed to be a very bright kid. He composed a lot of poems. If his life had been prolonged, he could have written many more. He could have become a great poet-saint. But he died at the age of eighteen.

The eighth Trungpa is known to have been a very great artist, particularly good at painting. He had a goatee and he used to love drinking a very thick tea. And he was very kind and gentle. He spent a long time practicing meditation, something like ten years. He locked himself in the top part of his castle, which had been given to him and his lineage earlier on.

We used to have the eighth Trungpa’s handwriting and his calligraphy and the thangka paintings that he did. It was similar to the thangkas we saw of the kings of Shambhala, that type. He actually did like thangkas of the eighty-four siddhas. They were very beautiful Gardri school paintings and fantastic works of art. And he compiled the library of Surmang, which was destroyed at the time of the tenth Trungpa.

The ninth Trungpa was supposedly a very shameful person, not in the sense of being wild or anything like that, but he just spent his life sitting around outside in the sun, chatting with people and taking anise snuff. He was very peasant-like and uneducated, actually. The only thing he composed in his life was four lines of a puja-type thing to Mahakala which we used to chant in our monastery and which doesn’t say very much. He was very ordinary. I think at the time there was not very much learning or very much intellectual work going on and there w as also not very much practice going on. And he just existed. His death w as supposed to be a quite interesting one. He kept saying, “Tomorrow I’m going to die. Since I’m going to die tomorrow, at least I’m going to die in a dignified way.” He called his attendant to come and take off his old clothes and put on his yellow robe. Then he sat up and he was gone—in the crosslegged vajra posture. That was the only testimonial that he knew what he was doing.

And then there is the tenth Trungpa. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you too much. If you like you can read about him in Born in Tibet, in which there are detailed stories. He was a great politician. He won lots of court cases which had been initiated against our monastery by various Gelugpa monasteries in our district. They were in league with the central Tibetan government, which actually finally invaded our monastery and sacked it. There was a court case going on afterwards and the tenth Trungpa was great, a very good politician. And he was also a great scholar. He had studied with Jamgon Kongtrul for a long time. Supposedly in his early life, when he was with Jamgon Kongtrul, he couldn’t get hold of butter to make a butter lamp. So he used incense to create a glow on the text just to be able to read a little bit. Then he would memorize what he had read.

And when he meditated he sat in a meditation box, which is a traditional thing. You have a little box that you sit in. You lean back at night and sleep in it. To get up you just lean forward. So you get up and you meditate all the time. And he supposedly tied his hair to the ceiling during sitting meditation so that if he nodded his hair would wake him up. He did that for about six years, actually. And sometimes he found that even that wasn’t effective enough, so he had stinging nettles arranged around the rim of his meditation box so that if he leaned over he would get stung by stinging nettles. He was a very tough person and once he set his mind to something, it never changed. He was born into the family of a local lord of the Surmang district. And he was very much into austerity. When he was searching for his guru he abandoned his monastery; he gave up riding on horseback, eating meat, wearing leather or leather products apart from wool, and so forth.

I think that’s most of the Trungpas.

Q: In something that I read recently, giving an account of the various Kagyu sects, it said that one of the small divisions was the Surmang Kagyii. I don’t know if that is true or not. But it said that there’s a separate sect, called the Surmang Kagyii, of which the Trungpas are the head. I wonder if that’s true and, if so, what characterizes this particular division of the Kagyii order.

R: Well, the interesting point is that the eighth Trungpa incorporated a great deal of Nyingmapa teachings, like Rangjung Doije’s role. He incorporated a lot of Nyingma teachings and be actually adopted Ekajata as the protector of Surmang monastery. Actually the Kagyiis didn’t ! have Ekajata. And earlier, the fourth 1 Trungpa’s characteristic teaching was that particular cho teaching, which made him very special. And we also have the Surmang version of the complete mandala performance of the Cakrasamvara sadhana, which was translated into a form of dance. That was the discovery of the teacher of the first Trungpa. Trungmase. Other characteristics of the Surmang Kagyu were that there was more research work done on the six yogas of Naropa and there were definitely more studies made on mahamudra by the Trungpas, particularly the fourth Trungpa’s commentary. Based on that the Surmang people had a great deal of information about mahamudra. They were experts on that. And in fact the fifteenth Karmapa, the predecessor of the present Holiness, actually invited Tenzin Rinpoche to teach him the Surmang Kagyu’s ideas about mahamudra.

But soon, you know, the fifteenth Karmapa died and Tenzin Rinpoche also died, so there was no chance to do that. So mahamudra seems to be one of their specialities, in which they are expert. And also bringing in the Nyingma tradition. The tenth Trungpa was very emotional about the Nyingmapa tradition. He visited Sechen monastery, he and Gyaltsap i Rinpoche, who was Jamgon Kong-trul’s teacher. They had sort of a spiritual love affair; the tenth Trungpa would say, “I wish I was born in your monastery,” and vice versa. There was a very moving experience before they left, before their parting. They went up to the roof and they sat together and chanted this tune of invocation to Ekajata, so that Ekajata would keep an eye on them after they departed and they would still be together. I think that not in a particularly flashy or extraordinary way, but in a very subtle way, the Surmang people have managed to maintain their intelligence somehow, and wisdom.

I think we should close our happening. It is twenty-five to three. Thank you everybody for coming to this seminary. I hope you will still keep continuing—somewhat. 1 think it certainly was a good idea. You’ve been good students, I must say. In spite of ups and downs.

Good-bye.

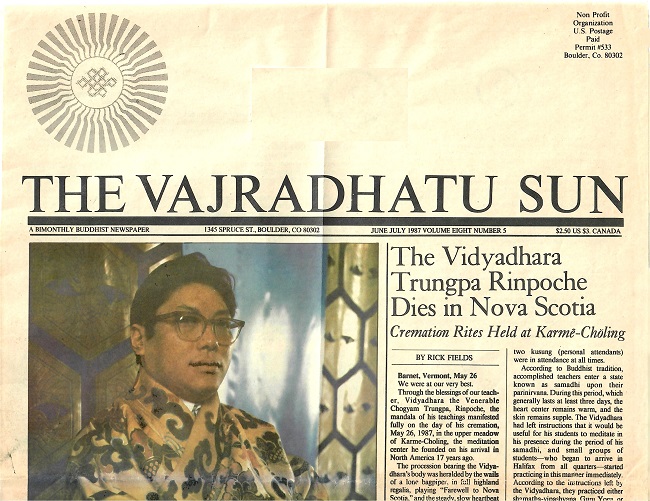

VAJRADHATU SUN JUNE JULY 1987

“The first Trungpa was a student of the siddha, Trungmase (fifteenth century), who was a close disciple of the fifth Karmapa, Teshin Shekpa (1384-1415). When Naropa transmitted the teachings of Vajrayogini to Marpa, he told him that these teachings whould be kept as a transmission from one teacher to one student for thirteen generations, and then they could be propagated to others. This transmission is called chig gyu, the “single lineage” or “single thread” transmission. Because of this, the Kagyu lineage is frequently called the “hearing lineage. Trungpase received the complete teachings on Vajrayogini, Chakrasamvara, and the Four Armed Mahakala, and these became a special transmission that he was to hold. Since Trungmase belonged to the thirteenth generation, he became the first guru to transmit this particular lineage of mahamudra teachings to more than a single dharma successor, and in fact he taught it widle. The first Trungpa, Kunga Gyaltesen, was one of Trungpase’s disciples who received this transmission. As the eleventh Trungpa Tulku, I received the Vajrayogini transmission from Rolpe Dorje, the regent abbot of Surmang and one of my main tutors.

Since 1970, when I arrived in America, I have been working to plant the buddhadharma, and particularly the Vajrayana teachings, in American soil. Beginning in 1977 and every year since then, those of my students who have completed the preliminary Vajrayana practices, as well as extensive training in the basic meditative disciplines, have received the abhisheka of Vajrayogini. There are now (1980) more than three hundred vajrayogini sadhakas (practitioners of the sadhana) in our community, and there are also many Western students studying with other Tibetan teachers and practicing various Vajrayana sadhanas. So the Vajrayogini abhisheka and sadhana are not purely part of Tibetan history; they have aplace in the history of Buddhism in America as well.”

Trungpa Rinpoche “Sacred Outlook”