The First 100 Years

by Richard Leviton

WE’VE FINALLY OUTDONE OURSELVES.

In a burst of precelebratory enthusiasm, we decided last spring to commemorate the 15th anniversary of our inception by commissioning a comprehensive took at hatha yoga in America, from its introduction in Chicago back in 1893 to its contemporary proliferation across heartland U.S.A.

Writer Richard Leviton, whose homeopathy cover story garnered so much praise just a year ago, courageously agreed to undertake the voluminous research and cross-country travel required to capture not only the spirit, but the remarkable moments, that have characterized yoga’s hundred-year efflorescence in this country. The result, all 20,000 words of it, promises to be the most authoritative coverage of the yoga movement for years to come.

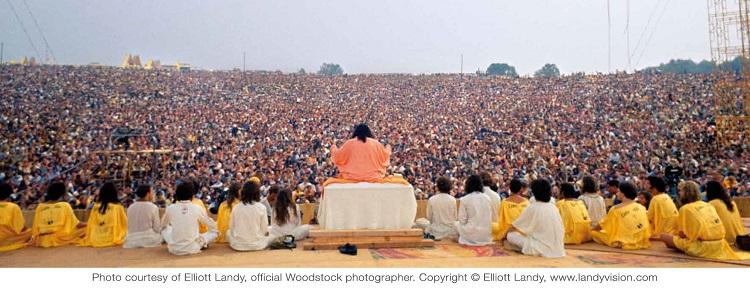

Part one, “How the Swamis Came to the States” tells the captivating tale of how Indian teachers and their diligent students have established yoga in a nation where, three quarters of a century ago, it was still considered a Hindu abomination even in liberal urban centers like Boston and L.A. All the major teachers and lineages have been covered, from Swami Vivekananda, whose talk at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893 galvanized his largely American audience, to Swami Satchidananda, whose benediction at the Woodstock rock festival invoked the spirit of a generation. We’ve also taken advantage of our expanded color capabilities to bring you yoga photos shot at sunrise against the sand dunes of California’s Death Valley.

Part two, “From Sea to Shining Sea,” is a documentary sampling of six yoga centers (and as many styles) in various regions of the country, including a small studio by the sea in Maine, a sweaty refuge for athletes and busy executives in downtown Manhattan, a junior college in Texas’ big sky country, and centers in urban San Francisco and suburban Atlanta and Chicago. Author Leviton, traveling with his yoga-teacher-wife Alonssi, has managed to recreate the unique ambiance of each venue. We think you’ll be fascinated to see how many guises yoga wears, and how many accents it speaks, as it takes to the mats in different parts of the country.

We hope you find this 15th anniversary special issue as enjoyable to read as it was for us to compile. We think it captures some of the variety and vitality that mark the American brand of hatha yoga – and we trust you’ll want to save it as a resource for future reference.

A comprehensive history of yoga in the U. S., from Swami Vivekananda in 1893 to Prospects for hatha yoga in the 1990’s

In the autumn of 1861 Lahiri Mahasaya, 34, a government accountant in the Indian military, a family man, and a yogi, sat in a cave in the Himalayas. He was about to receive an initiation from his deathless guru, the reputed avatar Babaji, that would one day help make yoga a household word in America.

Babaji, though immortal, had a distinct flair for the correct setting. He materialized “a vast palace of dazzling gold” to satisfy a secret wish of his young disciple, and then instructed Lahiri through the night in the ancient science of kriya, “the indestructible yoga,” which Babaji had rediscovered for this epoch. He told Lahiri it was the same spiritual science that Krishna had imparted millennia ago to Arjuna.

A deep purpose underlay the fact that Lahiri took his Himalayan initiation as a married householder, Babaji told him. His city life would make him a model of the ideal householder yogi. “The millions who are encumbered by family ties and heavy worldly duties will take new heart from you, a householder like themselves. You should guide them to understand that the highest yogic attainments are not barred to the family man.”

Lahiri’s initiation ended, and Babaji with his golden palace vanished. But the next morning as Lahiri made his way down the mountain, “consoled by his wondrous promise and rich with the newly found gold of God-wisdom,” his footsteps in essence were taking this spiritual treasure West, to America. There, with the birth of the 20th century, Babaji’s revelation of kriya yoga, in confluence with other powerful spiritual practices transmitted by other Indian teachers, would introduce a new impulse, a new orientation, that would transform the spiritual lives of millions.

In the past 129 years, many hands have planted and tended the tree of yoga in America. Today in 1990, as thousands of Americans of all ages – not renunciates, but householders with jobs – practice their asanas and pranayama each day and fold their legs for meditation, the tree of yoga is clearly flourishing in new soil. America, after all, though one of the world’s most materialistic countries, is also one of the most pragmatic. Yoga has burgeoned here because it works: It brings health, changes lives, even spiritualizes and liberates, depending on one’s level of engagement.

But as we settle down to practice, we can’t help but wonder, How did yoga ever come to this pluralistic, Christian country? The history of the yoga transmission from India to America reveals a continuous series of waves of influence, beginning in 1893. Each decade has brought another lineage of teachers, a new set of practices, another deepening of the yogic impulse – a multiplicity of practical ways to adapt and individualize this ancient Indian spiritual science to an ultra contemporary, secular America.

So Lahiri Mahasaya went back home to Benares, glorious as a rose of heaven, and quietly started a spiritual renaissance, according to Paramahansa Yogananda in Autobiography of a Yogi. Lahiri instructed students in kriya until his death in 1895, advising them that the image of the wandering ascetic was no longer appropriate. Instead, he told them, the yogis of the new age

should earn their own living, not be dependent on a hard pressed society for their support, and practice yoga in the privacy of their homes. Surely he had America in mind.

HOW THOREAU’s WALDEN POND MIXED WITH THE GANGES AND YOGA CAME TO AMERICA WITH SWAMI VIVEKANANDA

Peter Malakoff

EMERSON, THOREAU, AND THE TRANSCENDENTALISTS

Strictly speaking, the Eastern impulse arrived first by hearsay, through a handful of Indian sacred texts that made their way to an intellectual enclave in Concord, Massachusetts. There, beginning in 1841, such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott read, talked about, and wrote about the Bhagavad Gita. Although they may at times have mistaken the Gita’s religion – Emerson called it that “much renowned book of Buddhism” – they seem to have understood its spirit.

The contemplative Thoreau studied the Gita every morning at his Walden hermitage. “The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges,” he wrote. In 1849 he boasted to a friend: “Depend on it that, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.” Most probably Thoreau’s Headstands were strictly mental, but the Oriental impulse was registered in Concord and to a large extent disseminated throughout intellectual circles in America like a tiny spring flower poking through the thinning snow.

In 1878 William Henry Charming, another member of the Concord circle, persuaded Bronson Alcott, director of the Concord Summer School of Philosophy, to get his son-in-law’s new book published. This was The Light in Asia by Edwin Arnold, a Victorian-flavored biography of Gautama Buddha, which would soon go through 80 editions and sell half a million copies.

The next step in preparing the American soil for yoga came in September 1875 with the founding in New York City of the Theosophical Society. Helene Blavatsky, a free-wheeling, cigar smoking Russian emigre and occultist, and Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, a prominent New York lawyer, founded the society to promote Eastern esotericism in the West, allegedly under the direct guidance of Indian adepts. Blavatsky published two massive tomes – Isis Unveiled in 1877, The Secret Doctrine in 1888 – which put secret teachings from the Vedas and Puranas into the hands of American readers. By 1891 the Society had 54 U.S. branches, and the whole operation was being directed from India.

(Also see: Women in Yoga – A short history below)

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA, 1893

It would take the physical presence of an Indian teacher, ‘ however, to shift the involvement with Eastern spirituality from something intellectual to something practical and daily. This occurred in September 1893 with the arrival in Chicago of Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), all of 30, whose speech to the World Parliament of Religions ignited the largely American audience. He was kept busy for the next two years lecturing and teaching raja yoga in Detroit, Chicago, Boston, and New York.

Vivekananda was India’s ideal ambassador, observed Christopher Isherwood, British playwright/agnostic and a supporter of the Ramakrishna Order in 1940s America. “There was much in his nature which was akin to the American spirit,” said Isherwood. Vivekananda was college educated, a skeptic, yet deeply spiritual. His teacher had been Ramakrishna (1836-1886) of Dakshineswar (outside Calcutta), acknowledged throughout India as a saint of celestial proportions. Just before he died, Ramakrishna empowered his young disciple “to do great things in the world. Very soon he’s going to shake the world with his intellect and his spiritual power.”

At the end of a three-year pilgrimage through India, Vivekananda paused at Cape Comorin in the south and had a vision of a fruitful exchange of values between a religious India and a materialistic West. “In America is the place, the people, the opportunity for everything new,” he noted. “The Americans are quick, but they are somewhat like a straw on fire, ready to be extinguished.”

The Vedanta fires lit by the swamis of the Ramakrishna Order in America burned brightly for several decades, mostly on the two coasts. Vivekananda made a second tour of America in 1899, founded the New York Vedanta Society (still open), and gave group instruction in raja yoga. Four of his colleagues, who were direct disciples of Ramakrishna, arrived at the turn of the century. They would open two ashrams near Los Angeles, Shanti (1902) and Ananda (1923), and America’s first Hindu Vedanta temple, in San Francisco (1906). One hundred years later, the Vedanta spark thrives in America, with 17 centers throughout the country and a publishing house in Hollywood, California.

Hatha was “probably” not part of the formal practices taught by the Ramakrishna swamis, speculates Bob Adjemian, Vedanta Press publisher. “Privately they were given little exercises like a certain posture for stopping a cold.” Vedanta emphasizes the intellectual (jnana), meditative (raja), service (karma), and devotional (bhakti) elements, says Adjemian. “But certainly individuals practice the asanas for health purposes. In India hatha was more like physical education is here, not so special.”

Yet hatha continues to flourish, if modestly, within the Vedanta movement. Although not formally in the American Vedanta fold, the N.U. Yoga Center of Chicago, organized in 1972, is based on the teachings of Swami Narayananda (1902-1988), a disciple of Swami Shivananda (not to be confused with Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh), one of the dozen original students of Ramakrishna.

EARLY 20TH-CENTURY PIONEERS

The early missionary work of the pure Vedanta stream of the Ramakrishna Order prepared the ground in America. The seed of yoga had been planted. Meanwhile, other important contributory factors from the Orient were at work.

The California Gold Rush of 1848 brought 63,000 Chinese to California by 1870, and by 1900 there were 400 Chinese temples on the West Coast. The first Zen master ever to visit America, a Japanese named Soyen Shaku Roshi, spoke at Chicago’s World Parliament in 1893, and his student, Nyogen Sensaki, opened the country’s first Zen center in 1926 in San Francisco. Thus, while the Hindu tree of yoga was sprouting in America, a parallel, century-long transmission of Buddhism was also under way. And a few daring Americans followed the example of Blavatsky and Olcott and headed East in the early 1900s for some serious sadhana.

A stressed-out lawyer named William Warren Atkinson went to India in the early decades of the 20th century, studied with a guru named Baba Bharati, then returned as Swami Brahmacharaka. He published about 20 books and taught a modified hatha yoga system. Another American, renamed Pandit Acharya, abandoned a career as a New York playwright, somehow took initiation in yoga, lectured, wrote, and founded the Yoga Research Institute in Nyack, New York, in the 1920s. And on the West Coast, a yoga ashram was established in southern California’s San Marcos Pass by Rishi Singh Grewal, an Indian, whose numerous books on yoga and kundalini were published by the J. F. Rowney Press.

But the early history of how yoga came to America would have remained veiled in obscurity had not comparative American religions scholar Jay Gordon Melton drawn on the resources of his 30,000-volume library (including 5,000 books he inherited from the now-defunct Rowney Press) and an unflagging curiosity to put the story together. Among 15 books written by Melton, who since 1969 has directed the Institute for the Study of American Religions in Santa Barbara, California, is the Encyclopedia of the New Age (Gale Research, 1990). The “History of Hatha Yoga” entry alone is based on more than 100 yogi biographies and practice books.

“Hatha yoga in India had fallen by the wayside in the 19th century,” explains Melton. “But by the beginning of the 20th century and peaking in the first two decades, a revival had begun. It was part of the overall Hindu revival centered in Calcutta, which had been stimulated by the continual pressure of British thought and culture.” At that time a very well-preserved Paramahansa Madhavadasaji (1798-1921) organized a small circle of hatha practitioners in Bombay to reformulate the ancient yogic practices around more modern, scientific principles.

“What made them different,” says Melton, “was they tried to be scientific. They taught and sold hatha on its benefits to the body, rather than through its religious trappings.” Madhavadasaji’s remarkable longevity itself would surely have been a good marketing point. He was born in East Bengal into a family devoted to Vaishnaivism (Vishnu worship), was a disciple of Sri Gauranga Mahaprabhuji, and was versed in English.

T.K.V. Desikachar (left), whose Viniyoga emphasizes yoga therapy and individual instruction, studied for many years with his father, Sanskrit scholar and yoga master Sri Krishnamacharya (right).

Madhavadasaji had three principal disciples. The first was Sri Gopaldas, who was held in high esteem in India. The second, Swami Kuvalayananda (1883-1966), met Madhavadasaji in 1918 and trained with him until the great teacher’s mahasamadhi (death) in 1921. In 1921 Kuvalayananda founded the Kaivalyadhama Ashram and Research Institute and YogaMimamsa, its technical journal, at Lonavla, near Pune.

Kuvalayananda is regarded as one of India’s pioneers in physical education. By 1937, working through his numerous governmental administrative positions, he had developed an integrated program of scientific yoga and physical education. He conducted some 84 scientific experiments of yogic practices (such as the effects of pranayama on cardiorespiratory function and muscle tone), and he wrote several practice texts. In 1932 Yale University dispatched K. T. Behanan to train in yoga under Kuvalayananda, and some of his firsthand information made its way back to America’s academic cloisters via his book Yoga: A Scientific Evaluation.

It was Madhavadasaji’s third student, Yogendra Mastamani, 22, who would bring the fruits of Kaivalyadhama’s scientific yoga to America. In 1919 he landed in Long Island, where he would remain until 1922, establishing the first American branch of Kaivalyadhama. “Yogendra moved among the medical community, particularly the alternative physicians, teaching hatha yoga,” comments Jay Gordon Melton. “He introduced hatha as a discipline to northeastern America.”

During that period, in New York City, Yogendra met Benedict Lust, the founder of naturopathy. This was a watershed meeting because in the next decades hatha yoga would be introduced to America largely as an adjunct to the multiplicity of alternative healing techniques advocated by naturopaths.

In 1922 Yogendra returned to India, planning to revisit America. But in 1924 the U.S. restructured its immigration laws, setting a quota of only 200 Indian immigrations per year. Yogendra couldn’t return. “So what little hatha yoga there was then, grew out of the people Yogendra had influenced,” explains Melton.

One of these was Pierre Bernard, who began teaching tantric and hatha yoga to the “rich and famous” of Long Island. He was also associated with the yoga group upstate at Nyack. Theos Bernard, his nephew, studied with Pierre, then journeyed to Bombay in the 1930s to study directly with Yogendra. In the late 1930s Theos Bernard returned to America, took a master’s degree at Columbia University in Eastern studies, and in 1947 published Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience, which described yoga’s eightfold path and explained its asanas. “It became a major hatha sourcebook [in the 1950s],” says Melton.

The Madhavadasaji lineage returned to America in 1971 when Vijayendra Pratap, a student of Kuvalayananda, a researcher at Kaivalyadhama, and a Yoga-Mimamsa managing editor, accepted an invitation by yoga teachers to teach in New Jersey. In 1972 he established SKY Foundation in Philadelphia to propagate “classical yoga” – postures, breathing, relaxation, concentration, and meditation. Today about 300 students train every week at SKY yoga classes, and since 1973 the foundation has cohosted an annual conference (with the Yoga Research Society) on contemporary themes of yoga and world health, science, fitness, stress management, and parapsychology.

Pratap’s hatha style involves a gradual progression of asana, pranayama, mudra, then sound. “We base our practices on less energy expenditure, lower metabolic rates. We go slowly. We choose only certain practices – some postures, kriyas, bandhas, breathing, and meditation. The process of going into the posture is slow. You stay there a while, then come out slowly. The breathing in the posture is as natural as possible.” After the asana is mastered, breathing techniques are taught, then posture and pranayama are combined in “a complete body mudra,” says Pratap, followed by work -with chanting and “searching for the inner sound.” The SKY style is “strictly nondenominational, suitable for all ages and backgrounds, with the only requirement a personal commitment to self-improvement.”

It might surprise many people to learn that yoga has a long history in the United States. For a lot of Americans, their knowledge of yoga may only date back to the 1960s, when the concepts of spiritualism and meditation were embraced by the country’s counterculture.

But it may surprise some people to learn that yoga in the U.S. has a history that dates back to the late 1800s.

In 1883, Swami Vivekananda made an appearance at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago where he greeted his “sisters and brothers of America”, a salutation that brought a standing ovation from the large audience in attendance. His idea that all of the religions of the world are merely separate parts of a larger religion was a new concept to those hearing him speak about the mind, body and spirit.

Swami Vivekananda was followed by Yogendra Mastamani, also from India, who arrived in the U.S. and settled on Long Island, N.Y. in 1919 and established the American version of Kaivalyadhama, an Indian organization that made major strides in the scientific exploration of yoga. Mastamani introduced Hatha Yoga to the United States.

One year later, one of the most popular yogis of all time, Paramahansa Yogananda, arrived in Boston to introduce kriya yoga to the U.S. He created the Self-Realization Fellowship, which now has its headquarters in Los Angeles. Yogananda also wrote the world-famous best seller, “Autobiography of a Yogi”, a book that is still an inspirational resource for many yoga instructors and students.

In the 1930s, Jiddu Krishnamurti brought the yogi to new level of awareness in the U.S. thanks to this popular, eloquent speeches on Jnana-Yoga yoga, which is the yoga of discernment. His talks earned him the admiration of a number of celebrities of the time, such as writers Aldous Huxley and George Bernard Shaw and actors Charlie Chaplin and Greta Garbo.

In 1924, the U.S. imposed a restriction on the number of Indians it would allow to move to the U.S., meaning students who sought the teachings of yogis had to travel to India. One of these students was Theos Bernard, who traveled to India and came back in 1947 to write the book “Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience”, an influential book which is still widely today.

The same year that Bernard penned his examination of Hatha Yoga, Russian-born yogi Indra Devi opened one of the first Hatha Yoga studios in Hollywood and earned the title “First Lady of Yoga”. Devi was admired by housewives across the U.S., as well as Hollywood stars such as Gloria Swanson, Jennifer Jones and Robert Ryan. Devi died in her home in Buenos Ares in 2002.

But the man who is generally credited with introducing yoga to middle America is not even a native of India. Richard Hittleman, who studied in India for a number of years and returned to the States in 1950 to become a yoga instructor in New York, introduced a non-spiritual-based yoga to the United States and forever changed the way yoga was thought of and taught in America. It was Hittleman who placed emphasis on the physical side of yoga, letting a Western audience focus on the bodily aspects of yoga and not just the mind. Hittleman’s goal was to teach American students to gradually embrace the spiritual side of yoga, which many people have.

As Hittleman worked to expand yoga on the East, Walt and Magana Baptiste were working to increase yoga’s scope on the West Coast when they open a studio in San Francisco in the 1950s. Both of the Baptistes were students of Yogananda and Walt brought the influence of Vivekananda to the practice, creating an entirely new approach to yoga. Their yoga influence is being continued by their daughter and son, Sherri and Baron.

Elsewhere in San Francisco, Swami Vishu-devananda immigrated from India in 1958 and created “The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga” with famed artist and designer Peter Max. The book has become a go-to manual for yoga instructors and students. Vishu-devananga would later go on to create the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta yoga centers, which has become one of most prominent yoga school franchises in the entire world.

When the counterculture began to take hold in the 1960s, the idea of yoga and its emotional effects caught the interest of many people, and one of the most famous groups to explore the meditative possibilities of yoga were The Beatles, whose relationship with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was famous around the world. He created the Transcendental Meditation school of yoga that today employs more than 40,000 instructors and approximately 4 million followers worldwide.

In the late ’60s, Professor Richard Albert of Harvard took a journey into India and came back with the name Ram Dass and gave talks to college students around the nation in support of his blockbuster book “Be Here Now”, which set thousands of young people on a journey of discovery through yoga. The book continues to be source of inspiration for many people in their quest for spirituality through yoga.

In the 1970s, yoga continued to grow as studios began popping up all over the nation. The Mount Madonna yoga school, founded by Baba Hari Dass, gave residential yoga to the inhabitants of Santa Cruz, California. Shrila Prabhubada began the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, which led to the international spiritual study of Bhakti Yoga. Ashtanga-vinyasa Yoga was brought to the U.S. by Pattabhi Jois in the mid ’70s and made yoga popular with new groups of people. Swami Satchitananda was probably the most famous non-musician to appear at Woodstock. Swami Sivananda Radha is the female yogi credited with first investigating the link between the spirituality and psychology of yoga. And the teachings of Swamii Chidananda, who himself was a student of yoga master Swami Sivananda, were delivered to the world by one of his former students, instructor Liliias Folan through her landmark PBS television series “Lilias, Yoga and You” which aired on the network from 1970 to 1979 and made yoga available in every home in the U.S.

Yoga has continued its influence across America with classes and studios in cities all over, from the smallest town to the major metro areas. In addition, the advent of digital media, including CDs, DVDs and streaming Internet video, yoga can go anywhere, further giving it a foothold in the United States.

By: Linda Adams

Article Directory: http://www.articledashboard.com

PARAMAHANSA YOGANANDA, 1920

The next stage in the transmission of kriya yoga from Babaji through Lahiri Mahasaya to the West came in January 1894 in Allahabad, during the Kumbha Mela, India’s great religious festival. There Sri Yukteswar (1855-1936), Lahiri’s disciple, encountered the elusive Babaji. “Some years hence I shall send you a disciple whom you can train for yoga dissemination to the West,” Babaji told him. “The vibrations there of many spiritually seeking souls come floodlike to me. I perceive potential saints in America and Europe, waiting to be awakened.”

That disciple was Paramahansa Yogananda (1893-1952). In October 1920 Yogananda began to fulfill Babaji’s prophecy when he was invited to address the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, Massachusetts. His speech on “The Science of Religion” was well received and widely reprinted, and he spent the next three years in Boston. In 1924 Yogananda began a national tour, calling in at all major American cities, and in 1925 he founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles. “During the decade of 1920-1930 my yoga classes were attended by tens of thousands of Americans,” he wrote. A nonplussed Los Angeles Times called him “a Hindu invading the United States to bring God in the midst of a Christian community.”

That Hindu invasion has survived well on American soil. Today SRF has about 800,000 members worldwide, some 300 ordained nuns and monks, 250 affiliate U.S. groups, and nine temples in California and Arizona. Kriya yoga, explains SRF’s Bruce Mars, is “an advanced raja yoga technique that reinforces and revitalizes subtle currents of life energy in the body. As a result, consciousness is drawn to higher levels of perception, gradually bringing about an inner awakening.” Kriya yoga is an instrument through which human evolution can be quickened, explained Yukteswar. A half-minute of kriya equals one year of natural spiritual unfoldment.

“Hatha has a presence in the SRF kriya practices,” says Mars, but not a big one. “Our members mostly do hatha practice on their own to strengthen the body for meditation. We offer hatha classes in five of our temples. When Yogananda came in 1920 he taught hatha minimally as a great energizer for the body.”

ANANDA WORLD BROTHERHOOD

Hatha practice gained much greater prominence in the H kriya system through the efforts of one of Yogananda’s American disciples, Swami Kriyananda. James Donald Walters (b. 1926) became a direct disciple in 1948 and often publicly demonstrated Yogananda’s approach to yoga postures. He became a swami in 1955, ascended to the SRF vice presidency in 1960, then left the organization two years later over doctrinal disputes. Kriyananda founded Ananda World Brotherhood Village in 1968, a 700-acre residential community near Nevada City, California, where he formulated his hatha approach into a system called Yoga Postures for Higher Awareness.

“Each pose is an expression of a particular, spiritually helpful and uplifting state of consciousness,” explains Kriyananda. Yoga’s true purpose is not only “greater flexibility, radiant health, and other physical benefits, but heightened self-awareness – an invaluable preparation for meditation.” The practitioner should never strain into a posture, but seek “progressively deeper relaxation.” A distinctive feature of Kriyananda’s hatha is the recitation of an affirmation in each asana. In Matsyasana one says, “My soul floats on waves of cosmic light.” In Bhujangasana, “I rise determinedly to meet all obstacles.” The yoga postures, says Kriyananda, “are not only a series of physical positions, but exercises in mental awareness.” Following Yogananda, Kriyananda also emphasizes a series of energizing exercises (vigorous “double breathing”) and the importance of energy (prana) control in spiritual development.

Ananda has been offering a yoga teacher’s training certification program for over a decade, explains program administrator Valerie O’Hara. “Hatha for us is the physical branch of raja yoga,” says O’Hara, “and is practiced here as a preparation for meditation – to release physical and emotional tensions so that one can go more deeply into meditation. Students practice postures with an inward focus, a concentration on the breath, and an awareness of releasing energy blocks. Yoga postures are a tool for the expansion of self-awareness into Selfawareness gained by exploration, observation, and experience of the present moment.”

(see: Women in Yoga – A short history below)

Berlin-born Canadian Swami Sivananda Radha (Sylvia Hellman), a concert dancer by training, gesticulates at the feet of her guru, Swami Sivananda Saraswati, in the 1950’s

The Yogananda impulse eventually took different forms in a few other corners of America as well. In 1953 Kriyanandaji, another direct American disciple, began teaching kriya yoga, and by 1983 his Temple of Kriya Yoga in Chicago was offering instruction for students outside his inner circle. Roy Eugene Davis, ordained by Yogananda in 1951 and a kriya teacher since 1954, founded the Center for Spiritual Awareness in Lakemont, Georgia. Davis has written or published some 20 books and is still very active leading retreats and seminars.

BISHNU CHARAN GHOSH, 1938

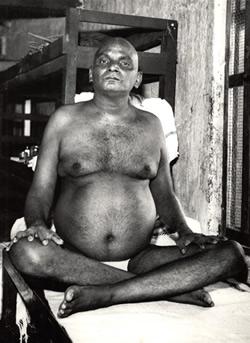

In his autobiography Yogananda is laconic about his childhood. He had four sisters and three brothers, the youngest being Bishnu Charan Ghosh (1903-1970). After Yogananda founded his Yogoda-Satsanga, a kriya initiation and practice school in Ranchi, India, Ghosh joined the faculty. Later he founded his own College of Physical Culture in Calcutta, which had an enrollment of 6,000 students and gained him an international reputation. In 1938, accompanied by his best student, Buddhabose, Ghosh headed west and for the next two decades traveled continually through Europe and America. He lectured on yoga, bodybuilding, weight lifting, and all aspects of physical culture and gave public performances of his own considerable prowess, strength, and muscular control. Columbia University professors were “amazed by demonstrations of the power of the mind over the body,” reported Yogananda.

Ghosh’s primary U.S. disciple is Bikram Choudhury (b. 1945), who declares with evident pride, “My guru was the highest authority on physical culture in America.” Dubbed the “Siddhartha of Hollywood” and the “Yogi Star of Beverly Hills,” Choudhury came to Los Angeles from Calcutta in 1970, after directing yoga schools in Germany and Japan since 1963, and immediately opened the first of many branches of his Yoga College of India.

In the past 20 years, the energetic Choudhury has opened an estimated 150 branch centers in 50 countries, and he claims his college has instructed three million students. It’s remotely possible. His Hollywood center alone has received 50,000 admissions since opening, and his current personal teaching load is 36 hours a week with large classes.

When Choudhury left India, Ghosh’s burgeoning center had a staff of 500 instructors. Ghosh individually prescribed asana sets for students, then the instructors showed them how to do the postures. “This is how yoga is practiced throughout India,” says Choudhury. “It’s individualized.” Lacking Ghosh’s prodigious staff, the inventive disciple reasoned that the American body is pretty much “a Xerox copy” throughout the culture. “Everybody’s joints are stiff, the spine is terrible, nobody can do backbends. Everybody’s shoulders are frozen like concrete. They all have a rabbit posture.”

So Choudhury choreographed a 26-asana sequence with which a student can reach “100 percent of a pure, internal body.” He claims that it’s very important to perform the 26 postures in his prescribed order. “Now in one class I can teach 50 students who have the same average physical problems with just these 26 postures.”

Choudhury’s asana sequence is really preventive medicine, he suggests. “It’s a vaccination for the average healthy person and an antibiotic for the patient. All people must have a healthy body first, then a healthy mind, always under their control. This is yoga for the householder. You don’t have to give up everything.”

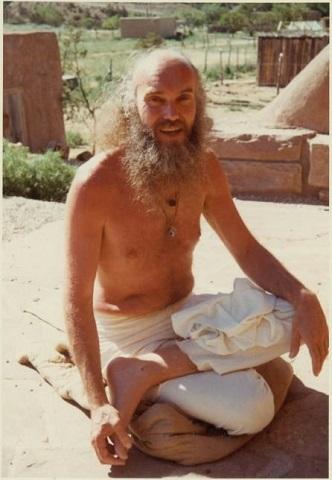

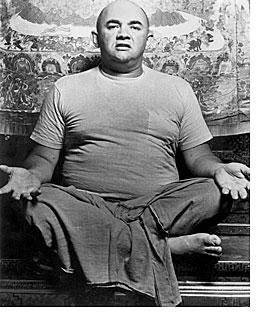

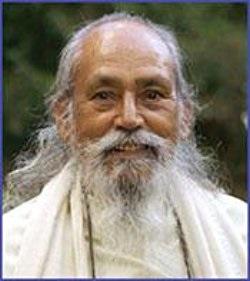

Swami Satchidananda came to the United States for “two days” in 1966 and ended up staying permanently. His Integral Yoga Institute includes an ashram in rural Virginia and over 40 branch centers worldwide.

SRI KRISHNAMACHARYA

Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1891-1989) was the wellspring of several major currents of American hatha yoga. His lineage was brought here by four of his principal students: Indra Devi (1947); his brother-in-law, B.K.S. Iyengar (1973); Pattabhi Jois (1975); and his son, T.K.V. Desikachar (1976).

Krishnamacharya began his yoga studies at age five under his father’s tutelage. Then as a grown man, he received the Indian equivalent of a Ph.D. in Sanskrit, Indian philosophy, ayurveda, and Vedic religion. In 1919 he traveled to the vicinity of Mount Kailash in Tibet, where he remained for seven and a half years studying with Rama Mohana Brahmacari. “My father was instructed in the use of asana and pranayama for people with sickness by this great yogi,” recounts Desikachar. Here Krishnamacharya also learned the vinyasas, the flowing sequences of movements and jumping-through style of yoga practice.

His austere Tibetan apprenticeship was immediately acknowledged and put to public use. In 1930 the Maharaja of Mysore, a learned Indian prince, appointed Krishnamacharya as his personal yoga teacher and in 1934 asked him to preside over his yogashala (yoga academy) at the royal palace, a position that lasted until 1950. In this capacity, Krishnamacharya gained a wide reputation as a yoga therapist who could help people with a range of physical problems – asthma, deafness, liver and heart complaints, even paralysis. He stressed that asanas must be individually adapted to students and that the programs must always be open to modification. Krishnamacharya also pioneered the use of various yoga props, such as chairs, stools, and bars, to help students prepare for the more stressful asanas. In the 1950s he moved to Madras and took on students, then in 1976 he founded the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, a state-certified yoga health care center with 20 teachers. By 1988 the center had taught over 7,000 students.

Krishnamacharya’s spiritual lineage goes back to the great 10th-century yogi Nathamuni, a preceptor of Vaishnavism. Nathamuni is credited with authoring two key texts – Yoga Rahasya (“Secret Doctrine of Yoga”) and Nyaya Tattva, both of which Krishnamacharya memorized. “I have been very fortunate,” says Desikachar, “because my father was kind enough to explain four sections of the Yoga Rahasya that he had learned by heart. Many of the features of Krishnamacharya’s teaching seem to be rooted in this text, for example, the use of breathing in asana.”

Sometime during the period 1934-1950, while at the Maharaja’s yogashala in Mysore, Krishnamacharya and his student Pattabhi Jois (b. 1915), also a Sanskrit scholar, discovered an ancient manuscript in a Calcutta library. It was printed on leaves, written in rhyming, metered sutras, and called Yoga Korunta, with an authorship attributed to a seer named Vamana Rishi. He described a complete system of yoga – several hundred asanas linked by flowing-through movements, or vinyasas, and done with breathing and bandhas. Krishnamacharya incorporated the Yoga Korunta into his own yoga methodology, and today the teaching styles of Jois, in particular, and Desikachar, to a lesser extent, include these techniques.

INDRA DEVI, 1947

The transmission of Krishnamacharya’s yoga to the West began with Indra Devi, popularly called the First Lady of Yoga in America. In 1947 she returned to Hollywood after studying with Krishnamacharya and opened her own yoga studio. Her epic biography reveals her immense contribution to the progress of yoga worldwide.

Born in Russia in 1899, Devi went to India in 1927 and in 1939 opened the first yoga school in China, in Shanghai. She introduced yoga to the Kremlin in 1960 and to Bulgaria in 1979, founded the Yoga Teachers Training Center in Tecate, Mexico, in 1961, and since 1982 has lavished her unflagging energies on Argentina, through her Indra Devi Foundation in Buenos Aires.

Devi has also taught and influenced a great many American yoga teachers. One of the best-known is Renee Taylor, a Belgian emigre and Hollywood scriptwriter, who taught with Devi in her Hollywood studio beginning in 1953. In the 1960s Taylor gained international fame for her books and films on the Hunzas, the long-lived, peaceful people of the Himalayas. Since 1964 she has maintained her Redondo Beach, California, yoga studio, where, with her staff and 20 branch centers, she teaches 600 students weekly.

The Indra Devi influence also made its way to Fresno, California, where Yogi Shalom (Charles Schoelen) has been teaching the Yoga of the Old Masters since 1964. According to Shalom, his method harkens back to the original purpose for doing postures: to slow down the brain pulse in preparation for the deeper aspects of yoga. Shalom studied yoga breathing with Selvarajan Yesudian (b. 1916), an Indian yogi based in Switzerland, then took asana instruction from Devi in 1964. In 1968 he opened the Yoga Center of Fresno, introducing his system of 80 postures in a sixpart yoga session.

B.K.S. IYENGAR, 1973

Probably the name most often associated with yoga in America today is Iyengar. B.K.S. Iyengar (b. 1918) studied with Krishnamacharya for several years in the 1930s, but his yoga career spans more than 50 years and many countries. He gained world prominence in 1954 when he left his native Pune, India, with one of his promising Western students, a violinist named Yehudi Menuhin, who brought him to teach in Switzerland. In the 1960s Iyengar trained Western students at European workshops; in 1964 his widely read Light on Yoga appeared, followed by Light on Pranayama – “a precious gem in the firmament of yoga,” declared Krishnamacharya – and his stature was secured. In 1973 Iyengar visited America (Ann Arbor, Michigan) for the first time, then in 1974 he came to California, and the American love affair with “the lion of Pune” began.

As with any movement, Iyengar had his early key supporters. One was Rama Vernon, who in 1974 became a lynchpin in the Iyengar transmission to America. With her San Francisco colleagues, Vernon laid the foundation for what would soon become the Iyengar Yoga Institute, the epicenter of one of the country’s largest, or at least most visible, yoga organizations. Today there are 100 U.S. Iyengar centers, 25 Canadian, and a “minimum” of 500 U.S. Iyengar teachers (100 in Canada), estimates Patricia Layton, Iyengar Institute director. Some 500 students a week take classes at the San Francisco studio alone, “the hub of Iyengar yoga in the U.S.” The 1990 Iyengar convention in San Diego (the third in North America; the first, in San Francisco in 1984, drew delegates from 17 countries) will have to set a lid on attendance at 750.

“I think Iyengar is the most visible yoga system today mainly because the teachers are extroverted, energetic people,” explains Layton. “They’re tied into using the body as a vehicle, working on the here-and-now plane. We’ve offered yoga more as a psychophysical discipline. Our idea is that life and yoga are one and that the purpose of yoga is to put you into contact with the most concrete things in life, to expand your awareness in this reality. So when we work with the body, it’s something concrete that everybody can relate to. This makes Iyengar yoga more accessible. Although the style is yang and tends to attract more males than other yoga systems, we still have six women for every man in class.”

The Iyengar style, generally speaking, emphasizes the development of stamina, strength, flexibility, balance, and concentration. A variety of props – benches, ropes, pelvic swings, sandbags, mats, blocks, chairs – are a mainstay of the practice. Precision in the execution of postures and meticulous anatomical alignment are particularly important, and here the physical ministrations of the instructor are often experienced. Iyengar has a reputation for skillfully `jumping” on students whose bodies haven’t achieved the maximum expression of asanas. The postural precision helps students dissolve “stubborn musculoskeletal blocks,” explains Layton.

Many well-known American yoga teachers have come out of the Iyengar camp: Arthur Kilmurray, Judith Lasater, Donald Mover, and Ramanand Patel in California, John Schumacher in Maryland, Mary Dunn in New York, and Karin Stephan and Patricia Walden in Massachusetts, among numerous others.

PATTABHI JOTS, 1975

Meanwhile, back in Mysore, Pattabhi Jois took up the development and mastery of the Yoga Korunta system. He formulated it into a set of 240 postures in six successive series and called the whole business Ashtanga Yoga. Jois had been head of the yoga philosophy department at the Sanskrit College of Mysore for 36 years, but after he “retired,” he continued teaching yoga classes six days a week (first class, 4:30 a.m.) at his yogashala, the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute. This center is also a highly regarded ayurvedic healing clinic. Then in October 1975 Jois and his son Manju, a teacher, made their first tour of America. Since then he’s been back six times, focusing on teaching students in Colorado, Hawaii, and California. Manju never left America and maintains a small teaching practice near San Diego.

In Jois’s Ashtanga, the six series of asanas are mastered sequentially. The primary series is called yoga chikitsa (therapy) with 75 postures; next comes the intermediate set, nadi shodana (nerve purification); then stira bhaga, which cultivates strength but requires great endurance. Very few of Jois’s Western students have mastered even the intermediate series, however. If there is an essential kernel to Jois’s Ashtanga, surely it’s this command from Yoga Korunta: “0 yogi, don’t do asanas without vinyasa.”

Vinyasa are flowing physical movements, “jump-through” connecting exercises that link every asana. The vinyasa most resemble an abbreviated Sun Salutation, which makes the 75posture set very demanding. Each movement is coordinated with ujjaya breathing, a special, forceful, throaty exhalation. Students lock their perineal and abdominal muscles (bandhas) in each posture to move vital energy upward in the body. The locks tone the body, control the breath, and direct prana, and it is imperative to “keep the heat up.”

The Jois Ashtanga system works when the body is hot and sweaty from the unceasing vinyasa movements. There is no pause in a typical 90-minute class because the overriding intention is to purify the body through heat. “Practice is most valuable when one maintains a continued progression of asanas,” says Jois, “so that the body rises to a crescendo of heat, then gradually cools down. Ashtanga Yoga is 99 percent practice, one percent theory. At times the practice can be painful, but it is very sweet pain. You will create the compact, strong, light body of a lion.”

Jois’s energetic yoga is only beginning to take root in America. Possibly this is because it takes “about a decade” to master, as some practitioners have wearily observed. In the early 1970s three Americans – Norman Allen, Clifford Sweet, and David Williams – took the full Jois teachings in India and, while they may have developed the bodies of lions, they aren’t teaching today. About a dozen Jois teachers are presently available in the U.S., including Beryl Bender and Tom Birch in New York, Brad and Linda Ramsay in Hawaii, and Jane MacMullen in San Francisco.

T.K.V. DESIKACHAR, 1976

The Krishnamacharya lineage sent another major taproot into American soil beginning in 1976 through the Viniyoga tradition of T.K.V. Desikachar (b. 1938). From 1961 until Krishnamacharya’s death in 1989, Desikachar worked with his father at the Yoga Mandiram in Madras. However, he didn’t start out as a yoga aficionado.

In his youth, Desikachar apparently found hatha yoga so “boring” he once climbed a coconut tree to avoid practicing. He took a degree in structural engineering in 1960, then a job with a Danish engineering firm, but five years into his career his father asked him to teach yoga to the renowned philosopher J. Krishnamurti. By this time the formerly bored Desikachar had become an engaged yoga teacher. He traveled with Krishnamurti to his centers in Switzerland and England in 1966-1969, then in January 1976 he gave his first American yoga course at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. Since 1986 Desikachar has made annual summer teaching visits to the U.S.

In a sense Desikachar never gave up his engineering background, explains longtime student Martin Pierce of Atlanta. “Partly because of his training as a structural engineer, Desikachar has a unique gift for looking at students’ bodies and seeing exactly what their problems are and what the exercises are doing for them. He sees bodies in terms of stress, leverage, torque, and fulcrum.” Or, as Desikachar puts it, “Yoga is basically a program for the spine at every level – physical, respiratory, mental, and spiritual.”

Like his father, Desikachar emphasizes the one-to-one interaction between teacher and student, and the individualization of technique, explains U.S. disciple Richard Miller, a founding member of Viniyoga America. “Viniyoga is the adaptation of yoga techniques such as asana, pranayama, textual study, meditation, counseling, imagery, prayer, chanting, and ritual to meet the needs of the individual.” Conscious breathing is precisely integrated into asana practice so that “extension occurs within the spine with each breath.” This sense of extension and adaptability to circumstance and student lies at the heart of Viniyoga and was reiterated in his July 1989 U.S. program, “Yoga and the Dynamics of Change.”

The silent master Baba Hari Dass, pictured here with children from the orphanage he founded in India, teaches a traditional version of eightlimbed (ashtanga) yoga at his Mount Madonna Center in California.

The continual adaption of asanas to the unique requirements of students – health, age, occupation, life-style, beliefs – is what Sonia Nelson, president of Viniyoga America and a Desikachar student since 1975, finds “so very exciting. The applications always follow the needs. Rather than imposing the form, in Viniyoga the form follows from the particular use of the asana by the student. The relationship of teacher to student, often in private classes, is strongly emphasized. That’s what makes the individual applications possible.”

Viniyoga America, with headquarters in Ojai, California, has 125 active members and a board composed of some of Desikachar’s core American students – Yan Dhyanski, Gary Kraftsow, Larry Payne, Martin and Margaret Pierce, Mary Louise Skelton.

SWAMI SIVANANDA SARASWATI

In his influence on American yoga, Swami Sivananda (1887-1963), the jagatguru of Rishikesh, is unarguably a pillar of equal stature to Krishnamacharya. Since 1954 the Sivananda wave has been cresting through America, with Yogi Gupta, Swamis Chidananda, Vishnudevananda, Satchidananda, Sivananda Radha, Vignanananda, and several other key lineage holders.

Sivananda was a spiritual polymath: medical doctor, teacher, prolific author, guru, indefatigable initiator of new projects. Born Kuppuswami Iyer in Pattamadai, South India, he took a medical degree, practiced in Malaysia, and from 1909 to 1913 published Ambrosia, a medical journal. Kuppuswami’s parivrajaka (the traditional period of ascetic wandering) took him to Himalayan Rishikesh in 1924, where he received initiation into the Sringeri line of Shankaracharya (one of Shankara’s 10 swami orders) from his guru, Swami Viswananda Saraswati. In 1933 Sivananda founded his Swarg Ashram Sadhu Sanga, then in 1939 his Divine Life Society, which in 1986 had 400 worldwide branches.

Sivananda’s zeal for initiating projects continued in 1948 when he established the Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy in Rishikesh, a formal yoga training center on the edge of the sacred Ganges, whose “whole object,” according to its founder, was to “make mankind spiritually vibrant. It will be a center for the generation of spiritual energy, whose currents are to reach kindred souls all over the globe.”

Sivananda was an exacting but benevolent taskmaster, as many of his older swamis now teaching in North America (Satchidananda, Vishnudevananda) will attest. “Yoga is a perfectly practical system of self-culture,” said Sivananda. “You attain a harmonious development of your body, mind, intellect, and soul by the practice of yoga. It is an exact science. It imparts to every practitioner definite practical knowledge of the means to enjoy fine health, longevity, strength, vim, and vitality. Yoga is the secret master-key that unlocks the realm of Elysian bliss and deep abiding peace.”

Sivananda also made a statement, possibly with America in mind, as he was about to dispatch several of his disciples westward. “Hatha yoga is not the goal. It is only a means to an end.

Take to raja yoga after possessing good health.”

The Sivananda Forest Academy currents began to waft to America in 1954. The first of his graduates to arrive was Yogi Gupta, aka Swami Kailashananda Jee Majaraj. Accepting an invitation to speak at a health convention at Chicago’s Morrison Hotel in August 1954, he left for the West as a Divine Life missionary with Sivananda’s blessing. “Now the time has come for you to go abroad and teach those in poor health and an unhappy state of mind,” Sivananda told him.

Yogi Gupta debuted in America as a practitioner of “authentic Raja yoga,” and his teaching was received with “immense interest,” as he stated in Yoga and Long Life (1958). This book, and its sequel, Yoga and Yogic Powers, were among the primary hatha practice texts for the late 1950s. Gupta went on to found the Yogi Gupta New York Center and the Yoga Foundation of America.

The next representative of the Sivananda lineage was Swami Chidananda, who undertook an extensive North American tour in 1959 as part of a three-year journey through Europe and the Americas on behalf of the Divine Life Society, of which he was then general secretary. While in Montreal, Chidananda called in at the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Society, directed by Sylvia Heck, 23, and Sita Frenkel, 20. Both young women had recently returned from solo trips to Rishikesh to study with Sivananda.

“Sivananda was extremely kind in taking care of me, like a father,” says Frenkel. “His personality was unbelievable: joyous, forceful, powerful. He took care of everybody.” After studying with Dr. Ramamurti Mishra at his Ananda Ashram in Monroe, New York, Frenkel and her husband, Hans, founded their own branch of the Divine Life Society in Harriman, New York, in 1964. There they received Chidananda on his subsequent American visits. In the late 1970s the Frenkels moved to the Washington, D.C., area and founded their Yoga Sadhana Mandir. Recently Sita Frenkel started a quarterly newsletter called Heart of Sivananda.

The Chidananda impulse took a different turn in the Pacific Northwest through Ralph and Lois Mitchell, who founded their Academy of Yoga and Psychical Research in Seattle in 1964 for “body, mind, and soul integration through hatha, raja, tantra, ancient wisdom teachings, ESP, and meditation.” In 1959 the Mitchells received Chidananda in Seattle, and their infant organization became a Divine Life Society branch.

Yogi Amrit Desai’s Kripalu Yoga is a spontaneous flow of postures directed by the “innate intelligence of prana (energy or breath).” Here Yogi Desai himself demonstrates his approach.

Certainly the most popular of Chidananda’s American students is the effervescent Lilias Folan, 54, the amiable yogini of PBS. Folan, married and the mother of grown children, began her yoga studies in 1964 with J. B. Rishi in Chicago and Swami Vishnudevananda in Montreal, then in 1973 she traveled to Rishikesh and studied with Chidananda.

Folan’s first PBS-TV series, Lilias, Yoga & You, was launched in 1970 through WCET TV in Cincinnati, and by 1977 over 200 stations carried it. So popular did it become that Time quipped, “Lilias promises to become the Julia Child of yoga.” The original series ended in 1979 after 500 installments, but in January 1989 Lilias returned to PBS with a new offering, Lilias! Alive With Yoga.

“Teaching on television is like having a yoga class with thousands of students,” says Lilias today. The core of her teaching, she says, whether on TV, in books, or in workshops, is “service and universal love. I have only the burning desire to communicate yoga. The outer body before the TV is very tight. When people begin to move, to breathe, to relax, there is a soft inner body that begins to awaken. There is more in my new PBS series of tuning in to a contented silence. It’s daring to be silent on television. But a relaxed state is a humble, loving state, releasing all our self-concepts.”

SWAMI VISHNUDEVANANDA, 1958

T he next Sivananda wave came in 1958 with the arrival in San Francisco of Swami Vishnudevananda (b. 1927). Perhaps “tsunami” would be a better way to describe it, because if nothing else – and he is many things – Vishnudevananda is a fabulous yoga businessman who has found alluring, innovative ways to market the yoga experience – yoga camps, exotic vacations, conferences, teacher training courses. Through these programs, he has introduced many thousands of Westerners to the fundamentally spiritual principles of the Divine Life Society. “Swami Sivananda revolutionized yoga, both in the East and West, in recent times,” says Vishnudevananda, but the same can equally be said of him. “Swami Vishnu was a man with a push,” says his colleague, Swami Chidananda.

In 1946, after two years in the Indian army, the young Thankaswamy arrived at Sivananda Ashram in Rishikesh. There he remained for 10 years, training in all aspects of yoga. In 1949 he became a swami, and in the 1950s he was the principal hatha instructor at the Forest Academy, India’s only center for formal, systematic yoga training. Everyone spoke English because Sivananda knew that “English was going to be the future world language in the coming century. One day in 1949 he said to me, `Swami, you go to the West.’ I protested, but in December 1957 I did come.” After a brief residency in New York City, Vishnudevananda established his headquarters in Montreal, and in the past 23 years his Canadian organization has mushroomed.

Founder of the Himalayan Institute in Honesdale, PA, Swami Rama teaches the philosophy and practice of raja yoga. Instructors at the institute offer hatha yoga as a preparation for meditation.

When Vishnudevananda discovered that his Montreal students flocked 50 miles north in the summertime to the cool Laurentian Mountains to escape the urban heat, he followed them, founding his first Sivananda Ashram Yoga Camp in Val Morin, Quebec, in 1961. Today the 350-acre facility offers hatha classes, meditation, vegetarian meals, mantra chanting, a swimming pool, a sauna, picnics, nature walks, sophisticated conferences. It’s “a place to relax, renew, contemplate, and tune in to the stillness within.” By 1977 Vishnudevananda had opened more camps in Kerala, India; Woodbourne, New York; Grass Valley, California; and Nassau in the Bahamas, birthplace of the yoga vacation.

Nassau is a favorite location for Vishnudevananda’s fourweek teacher training course, as well as special Easter and Christmas programs. The training program curriculum, in practice since 1969, and from which some 5,100 students have graduated at the current rate of about 300 per year, includes instruction in asanas, pranayama, mantra, japa chanting, cleansing, kriyas, scriptural study, anatomy and physiology, yoga and Vedanta study, and daily selfless service.

The 1989 summer training program generated some interesting demographic data, according to Swami Padmapadananda at the Val Morin headquarters. “We found the people taking up yoga are health care professionals, psychologists, nurses, artists, householders, and college students.” At one session of 103 students drawn from 14 countries, 16 percent were Americans, 12 percent Canadians, 15 percent Spanish, 13 percent French, and 56 percent women. The average age for 81 percent of the students was 20 to 49, of which 50 percent were single, 25 percent married, 14 percent divorced, and 26 percent without children. Half the students had outside employment, but 26 percent were self-employed; leading professions included education (27 percent), health (17 percent), and business (11 percent).

Five essential principles are always emphasized in any Vishnudevananda program. “Yoga is a complete science of self-discipline,” says Vishnudevananda, and it’s based on proper exercise, breathing, relaxation, diet, thinking, and meditation. “By following these points, yogis discover the real goal of life – God realization.”

“The list of prominent yoga instructors who began their training with Swamiji would fill a mini yoga teachers guide,” comments Karen Minsberg of the Val Morin office. One of these prominent yogis is Ganga White, who studied with Vishnudevananda in 1967, opened his own Center for Yoga in Los Angeles, and since 1983 has directed the White Lotus Center in Santa Barbara, California.

For five years White was vice president of the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Society in Val Morin and received various yoga teacher honorifics (Yoga Acharya, Yogiraj) from the Yogi Niketan and Sivananda Ashram in India. Kudos notwithstanding, White was never a company man. His true preference, he admits, is an eclectic, nondogmatic synthesis of classical and contemporary techniques drawn from the best major systems today, including Iyengar, Jois, and Krishnamurti.

“Everything we do at White Lotus Foundation is meant to empower the individual, not to make him or her conform to dogma,” states White. “We aim to awaken the fire of yoga within each student. The majority of people come here with the intention of learning asanas. They leave thinking in terms of transformation.”

Another American Sivananda pioneer, Sylvia Hellman (b. 1911), studied with Sivananda in Rishikesh in the mid-1950s, then returned as Swami Sivananda Radha in 1957 and opened her Yasodhara Ashram in Burnaby, near Vancouver, British Columbia. She was the first Western woman to take sannyasa initiation from Sivananda.

Born in Berlin to wealthy parents, Swami Radha had from childhood “a sensitiveness, an extrasensory awareness, which brought occasionally happy, but most often, sad revelations.” It was through her innate clairvoyance that Radha first met her guru, who was able to “project himself to me in Canada,” she recounts in her autobiography, Radha: Diary of a Woman’s Search.

Radha, a successful concert dancer, had emigrated to Montreal in 1951 and was ethereally beckoned east by Sivananda in 1955. In 1963 she relocated Yasodhara to its present location on Kootenay Bay, an 83-acre retreat in the Canadian Rockies – “the Himalayas of the West,” she calls it. In 1981 Radha began establishing five Shambhala Houses (four in Canada, one in California) “to provide a connection to the teachings, which helps to keep the initiative going.”

Since 1969 Yasodhara has trained students in Radha’s distinctive hidden language approach to yoga. Here the physical aspects of an asana are combined with the inherent symbolism, the secrets, and the metaphorical connotations. In Tadasana, for example, the student reflects, “What does a mountain mean to me?” Possible responses: standing up, standing still, upright. Each asana becomes an invitation for deep psychological reflection, even visual, symbolic participation. Radha’s asana sequence groups the contemplative postures according to structures, tools, plants, fish/reptiles/insects, birds, animals, and ends with Savasana.

“As Westerners we have to start within our own culture and go as far as we can with Western psychology, using some of the yogic approach,” says Radha. “Even yoga psychology is not sadhana; it is a preparation.” Other elements of Radha’s pedagogy include kundalini, prayer dance, divine light invocation, mantra, dream interpretation, and “intensive self-investigation.”

SWAMI SATCHIDANANDA, 1966

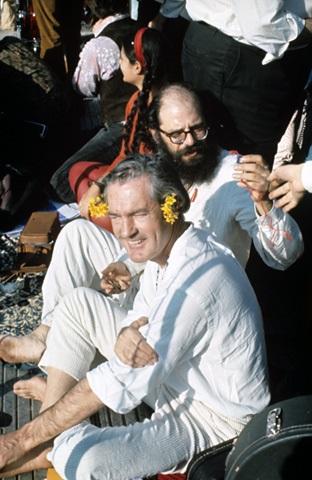

The year that saw Swami Radha teaching Hidden Language Yoga in British Columbia, 1969, also witnessed a pivotal moment in American cultural history on a Catskill farm in New York State – Woodstock. About 500,000 young, mostly stoned Americans gathered for the communal rock epiphany of a generation. Opening this muddy, euphoric, psychedelic love-fest with a brief talk and blessing was a tall, bearded, longhaired man in orange robes. To the assembled multitudes, he must have looked like an a radiant, aging hippie.

“My beloved sisters and brothers,” he began, recalling Vivekananda’s egalitarian invocations of 76 years earlier in Chicago to an earlier generation of Americans. “I am overwhelmed with joy to see the youth of America gathered here in the name of the fine art of music. The future of the whole world is in your hands. The entire world is going to watch this. The entire world is going to know what the American youth can do for humanity.”

The guru of Woodstock was Swami Satchidananda (b. 1914), whose appearance helped midwife the 1960s psychedelic hippies’ rite of passage into the 1970s of sadhana, spiritual communities, and yoga.

Satchidananda had only meant to visit America for two days when he accepted the invitation of two American artists (Conrad Rooks and Peter Max) in 1966. Instead, he ended up staying permanently, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1976. In his 24 years in America, Satchidananda has helped transform Woodstock into Yogaville. Born in South India as C.K. Ramaswamy, he took his sannyasa initiation from Swami Sivananda in 1949. After a successful All India lecture tour in 1951, which saw the creation of numerous new Divine Life Society branches, Satchidananda went south to Kandy, Ceylon, where he remained from 1953 to 1966, when the filmmaker Rooks lured him out of his sedate ashram into the uncharted wilds of America.

Satchidananda responded with maturity and quickly converted the natives. In 1968 he opened his first American Integral Yoga Institute branch (IYI) in Manhattan, with a yoga ashram upstate in Port Jervis, and by 1973 he had established lYI’s country ashram in Pomfret, Connecticut. In 1979 IYI acquired nearly 1.000 acres in rural Buckingham, Virginia, and July 1986 saw the ecumenical dedication of lYTs $2 million Lotus Temple complex, graced by a 110-acre lake. Yogaville was thereby set deep into the subsoil of American life. Today it offers a holistic health clinic, a publishing company, pilgrimages, conferences, training programs, retreats, and oversees 40 branch IYI centers around the world.

The two adjectives that best describe Satchidananda’s teaching are “integral” and “ecumenical.” Integral Yoga is virtually a yogic formula, a uniform prescription observed throughout the 40 centers involving asanas, pranayama, selfless service, concentration, meditation exercises, mantra, devotion to God, and ceaseless self-inquiry. Typically a hatha class follows a standard, tested procedure, lasting 75 minutes and including, if only in small portions, all of the IYI elements. Integral yoga means “the entire yoga – yogic living, yogic thinking,” explains Satchidananda. For him, the essence of yoga is “easeful physically, peaceful mentally, and useful in life.”

Part of that usefulness takes a very ecumenical, diplomatic turn. Ecumenicism has been foremost in Satchidananda’s mission, from his reconciliation work in Ceylon and his pioneering visits to the Soviet Union as a spiritual ambassador since 1985, to the architecture, iconography, and liturgy of the Lotus temple, which honors all world religions. “Over the past 10 years a global spirituality has been emerging,” he observed in 1985. “Now it is visible everywhere. That universal, ecumenical spirituality is what we call yoga. “

The tumultuous year 1969 also saw the arrival, with less fanfare, of another Sivananda disciple, in Miami, Florida – Swami Jyotirmayananda (b. 1931). He became a swami in 1953 at Rishikesh and remained there until 1962 as a professor of yoga and Vedanta philosophy at the Divine Life Society. From 1962 to 1969, Jyotirmayananda taught yoga in Puerto Rico, then came north to Florida, where he established his two-and-a-half-acre urban ashram, the Yoga Research Foundation, in a commercial district of the city. The institute publishes the monthly International Yoga Guide, distributes Jyotir- mayananda’s numerous books and tapes, and offers a home study course, seminars on the scriptures, teacher training seminars, and daily hatha-pranayama classes.

“The Americans are quick, but they are somewhat like a straw on fire, ready to be extinguished.”

“Our classes emphasize stress management and balancing pranic flows,” says Michael Phillips, spokesman for the foundation. “Hatha is great for getting the body into shape for meditation. Our hatha program does not have a beginning or an end. It’s simply ongoing. We use the same exercises to keep the body in shape and the spine flexible.”

Out in Berkeley, California, a younger Sivananda representative started using the same exercises but with a new twist. In 1973 Swami Vignanananda (b. 1932) added a new, vital element into the execution of each asana: pranayama.

“As the postures are held, we breathe with precise, deep, rhythmic techniques at various rates and depths,” explains Saraswathi Devi, vice president of the Prana Yoga Ashram, which has 50 branch centers worldwide and a rural ashram in Lower Pottsgrove, Pennsylvania. “Sometimes it’s a strong, forceful, nostril breath, what Swamiji calls ‘a deep, speedy breath.’ Sometimes we use a bellows breath, or a long, slow, smooth breath; and occasionally we hold the breath. We find the mind becomes focused. There’s a tremendous feeling of lightness, peace, and energy, along with an enhancement of the explusion of toxins from the body.” Students are encouraged to work their own way into the postures and to avoid forcing a mental notion of what the technique ought to be, adds Devi. “We try to foster a sense of growing from within.”

The Berkeley ashram offers 14 hatha classes every week, and about 200 people take advantage of the morning and evening sessions. The style is relaxed and noncompetitive, and students receive individual attention while they work at their own level.

SRI BRAHMANANDA SARASVATI, 1955

Before he came to America in late 1955, Dr. Ramamurti Mishra was a chief physician, neurosurgeon, and professor of medicine in Bombay. Born into a wealthy Benares family, he had earned a degree in Sanskrit studies, followed by his medical diploma with a specialty in endrocrinology and psychiatry. Mishra’s fluency in Eastern spirituality and Western allopathy is evident in his two important texts, published in the late 1950s: Fundamentals of Yoga and The Textbook of Yoga Psychology. Three years after coming to the U.S. he founded the Yoga Society of New York; in 1964 he established the 100-acre Ananda Ashram in upstate Monroe and in 1972 the Yoga Society of San Francisco. .All three continue today, teaching hatha, Sanskrit, and Mishra’s yoga of knowledge, traditionally called samkhya yoga, which means “complete, exact, and positive knowledge.”

Mishra’s own exact, positive knowledge of the spiritual path convinced him to don the orange robes of the sannyasin in 1983, when he took on the name Sri Brahmananda Saraswati. He credits many teachers and initiators in his spiritual preparations, but perhaps the guru most prominent in his sadhana was a mystery yogi named Bhagwandas (c. 1857-1957), who was almost a century old when Mishra met him in Bombay. He came from the north, from what is now Pakistan. “He was fully enlightened and certainly transmitted something real that we can feel in our teacher,” observes Bharati, Sanskrit specialist and spokeswoman for Ananda Ashram. Bhagwandas disdained publicity, accepting only a small circle of hand-picked students, but for Mishra, who had encountered his fair share of Indian luminaries, Bhagwandas’s light was “full enough.” Throughout its 26-year history, Ananda Ashram has been a watering hole and spiritual salon for many of America’s well-known gurus. “Our ashram became the host for many teachers who came to the East Coast from India,” says Bharati. Swami Satchidananda kept a guest cottage on the grounds, and between 1966 and 1971 he used the ashram for weekly yoga retreats. Yogi Vithaldas came up often from Manhattan. “This was an open place,” says Bharati. “We’d have everybody stay and give lectures. We gave them a platform. We weren’t sectarian. The original scriptures – Bhagavad Gila, Vedas, Upanishads – came long before any sectarianism. You can get in touch with the universal true spirit of yoga. We’ve had the privilege through Sri Brahmananda of direct access to the Sanskrit teachings.”

Hatha classes at the Ananda network are offered five times a week at all three U.S. locations, and have been, ever since their respective foundings. Ananda’s main emphasis, says Bharati, is raja yoga: direct Sanskrit classes, including chanting, grammar, conversation, and “the direct approach” to the scriptures. For Sri Brahmananda, the true purpose of yoga and all healing is to gain access to “the absolute, perfect, and limitless Reality, to get beyond the prison of body and mind, time, and space. That is the real healing. Otherwise there is no meaning in any discipline.”

RICHARD HITTLEMAN, 1961

The yoga movement started entering the American mainstream in the 1950s through a major new impulse from a Westerner trained in India. Nearly a decade before Lilias Folan’s PBS debut, Richard Hittleman (b. 1927) began presenting hatha yoga to a national TV audience through his Yoga for Health series, which first aired in Los Angeles in 1961. But Hittleman’s debut had a great deal of momentum and preparation behind it.

An inestimable number of Americans began their hatha practice after watching Hittleman on TV or reading any of his mass market yoga texts, which by 1990 have sold over 10 million copies. To a considerable extent, Hittleman’s pioneering of forthright, nonreligious hatha yoga, beginning in 1957 when he opened his first Florida yoga studio and continuing through 1990 with the release of new instructional videos, ushered in the great hatha boom of the 1970s.

Today, at 63, Hittleman lives at the Yoga Universal Ashram in Scotts Valley, California. He took his first hatha class in 1936 from a middle-aged Hindi who worked as a handyman at his family’s upstate New York home. This man taught the aspiring young yogi breathing, meditation, and asanas. But what most remained with Hittleman in years afterward was what he said about prana. “He described the nature of prana, the life force that is in the air; he told me it sustains our lives and how we can change our lives by changing our breathing.” With his first eye-opening lesson, Hittleman’s life trajectory was set in motion. He took a master’s degree at Columbia University Teacher’s College and while there in the late 1940s gave yoga and meditation classes. Then he went to India and immersed himself in the dar- shan of various gurus, including his principal teacher, the sage of Arunachala, Sri Ramana Maharshi (1880-1950). Maharshi, although self-awakened, without teacher or lineage, was of the advaita vedanta temperament.

When Hittleman returned to America, he realized he’d have to couch his yoga insights in terms and practices acceptable to Eisenhower Americans. It was a pragmatic tone that would virtually set the teaching style for hatha yoga for the next two decades. Hittleman decided to emphasize yoga’s physical, health benefits and its contribution to flexibility, stress reduction, stamina, coordination, weight regulation, muscular firming, and emotional quieting.

“Few people in the Western world are more subject to the anxieties, tensions, and physical and mental ailments that are integral to a computerized, technological society,” Hittleman said in 1968. “Hence the attraction of yoga – with its promise of relief from physical and spiritual malaise. As we therefore proceeded to present yoga primarily in a physical context, interest in it began to grow.” Hittleman reasoned that eventually Hatha’s health benefits would be so pronounced that the student “would then desire to learn more of the philosophy and to practice the meditation techniques. These were, after all, the entire ‘essence’ of the subject.”

YOGA IN THE SIXTIES

The number of Americans exposed to yoga in the early 1960s was quite small, says Hittleman. But in 1965 the lifting of the 40-year lid on Indian immigration dramatically changed all that. Suddenly Indians and other Asian nationalities could immigrate freely, and a remarkable wave of gurus began to surge through 1970s America, fulfilling, perhaps, that “Hindu invasion” a baffled Los Angeles Times had announced in 1925. Indian admissions for 1965 were 6,000, a figure that soared to 14,000 the next year and to 30,000 by 1969.

Other factors with major sociological impact were also in motion. America was, after all, in the throes of the ’60s, that tumultuous decade of psychedelic drugs, be-ins, radical politics, civil rights marches, and Vietnam war protests. At the turn of the decade, in 1970, Baba Ram Dass (formerly Richard Alpert of Harvard, born 1932, fired 1967) made his apocalyptic college campus tour, a Pied Piper with stringy gray beard, beads, white clothes, sitar, and spiritual revelations from beyond the pall of LSD. Ram Dass came back from India with a Ph.D. in bhakti yoga, and for North Americans he turned the spiritual quest into a life-style.

Ram Dass even provided new recruits with the cookbook for a sacred life, “dedicated to those who wish to get on with it,” Be Here Now, published in 1971 and widely distributed. Here Ram Dass extolled the glories of sadhana, gave practical instructions for pranayama and hatha yoga, and outlined the complete path of raja yoga.

While Ram Dass and his traveling sadhu road show illumined for many the range of Eastern spirituality available to post-1960s survivors, another event, just five years earlier, had already introduced the key words. This was the publication in 1965 of Jess Steam’s best-selling narrative, Yoga, Youth & Reincarnation. Here he described his three-and-a-half-month 1964 immersion in the yoga ashram of Marcia Moore in Concord, Massachusetts. After approximately 115 years yoga had returned to the Concord of Emerson and Thoreau, but this time somebody was actually doing Head- stands.

“In Marcia Moore I would have a distinctly American guru, often Goddesslike in posture, who would consider the Occidental temperament at every learning level,” wrote an adulatory Stearn. Moore’s family owned the Sheraton hotels and had lots of money, so after her graduation from Radcliffe in the 1950s it was not an acute financial burden for the young Moore to travel through Kashmir, Kalimpong, and Shantiniketan in India, nor to rent a commodious 10- room house as a base camp. She studied hatha yoga with Roman Datta, an English-speaking Calcutta businessman and Theosophist, and then with Vish- nudevananda, Yogi Vithaldas, and Rama- murti Mishra.

Back in Concord, Moore turned her home into a yoga studio and taught regular classes with her husband, Louis Acker. “I tell women that yoga is the best beauty course they can get,” said Moore, not altogether impishly, for she knew well that many of Hollywood’s celebrities – Garbo, Gloria Swanson, Olivia de Havilland, even Israel’s prime minister, David Ben-Gurion – recognized that Shoulderstands enhanced vigor and wellbeing.

Stearn dutifully practiced asanas through his 100 lessons and left Concord a changed man. He felt himself “trained in a new style Yoga for the 20th century, for the volatile Westerner” – not to mention his introduction to Moore’s other specialties of astrology, past lives, and psychism. “For the first time in my life I felt myself in harmony with the universe around me. It was a good feeling.” Millions of Americans heeded his sincere, inspiring report, and the hatha boom received another boost forward.

BHAGAWAN NITYANANDA

The year 1958 saw a significant early presence in America of Kashmir Shaivism. This religion of Shiva is possibly India’s oldest and may predate Vedanta and the Aryan invasion. Its principal carrier to the U.S. was a plump, ebullient American Jew and Oriental art dealer from New York City named Rudi – short for Albert Rudolph (1928-1973) and Swami Rudrananda. Although Rudi was schooled in Kashmir Shaivism, in a deeper sense his teaching was “a spontaneous transmission arising without lineage,” as Dingo Khyentse Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher, described it.