The following is from

Fall 1996

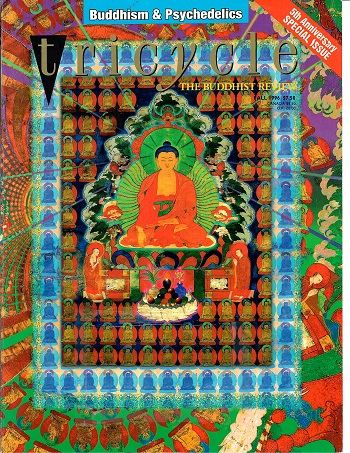

Psychedelics & Buddhism

A High History of Buddhism

by Rick Fields

Rick Field’s books include How the Swans Came to the Lake (Shambhala Publications), The Code of the Warrior (Harper Collins), Instructions to the Cook, and mostly recently before his death, Fuck You Cancer. He was the editor of Yoga Journal for many years. He died in 1999 in Fairfax, California and is survived by his wife Marsha Cohen, who gave me this article first published in Tricycle Review.

This issue of Tricycle can be ordered by going to: http://www.tricycle.com/

That practice can be helpful. even lifesaving, to the strung out is of course good news. But there is another sort of good news, for some unreformed heads at least. There is something of a psychedelic revival going on these days – and more than a few Buddhists are taking part in it. The sacramentals are partly the old familiar (LSD),the new (Ecstasy and other designer drugs), and the ancient (plant entheogens such as mushrooms, peyote cactus, and the Amazonian ayahuasca). Interestingly, it is the last category; the ancient plants used by the oldest indigenous peoples on the earth, that seems to hold the most promise for the future.

There are a number of reasons for this psychedelic revival. For one thing, psychedelics have proven to have a certain staying power. Stamped down countless times, abandoned for various reasons, they nevertheless somehow manage to pop up like mushrooms from one generation to the next. Timing is also a part of it. A dynamic back and forth relationship between psychedelics and Eastern spirituality has existed since the nineteenth century. In the fifties Buddhists and Hindu texts inspired aristocratic British exiles like the writers Gerald Heard and Aldous Huxley to seek an experiential illumination through psychedelics. In the sixties the same psychedelic experience inspired American academicians like Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) to investigate Eastern texts and practices.

During the eighties the use of MDMA (Adam, Ecstasy) became fashionable, both among psychotherapists and in the new youth culture in the rave and dance club scene. Ecstasy is not a hallucinogen or entheogen, but has best been described as an empathogen: it seems to relax the stranglehold of the individual ego and open the way to an unusually high level of intimacy and communication (hence its popularity with marriage counselors). The general calmness, serenity and spaciousness of the experience has led, in some circles, to its being called the “Buddha-drug.” If psychedelics correspond (for some at least) with Tibetan or tantric Buddhism, then Ecstasy could be seen as the Mahayana or bodhisattva drug of choice. In fact, at least one rumor tells of a serious circle of practitioners who use Ecstasy as a support for their metta (loving-kindness) practice.

During the seventies and eighties, psychedelic drug use seems to have been largely discounted in Buddhist communities, as it was in the larger culture, though it was not entirely absent from either arena. It simply went underground. Buddhist groups quite understandably were anxious to stay on the right side of the law and seemed as anxious as most organizations to separate themselves from the sixties’ drug and antiwar countercultures. And individual students were growing older, taking on the responsibilities of families and careers. For most students psychedelics were remembered as a boat that had gotten them to the other shore of real practice but was now a distraction to be abandoned.

But just as in the larger culture, a small number of students continued to experiment with psychedelics when they were off duty, in the “post meditation state.” Most of these, perhaps, fell into the post sixties fashion of using psychedelics for largely recreational reasons. A loosely floating post hippie tribe of Buddhist Deadheads, the Dead Buddhists of America, kept some thing of the old spirit alive. When Jerry Garcia died in 1995, the editor of their ‘zine, The Conch Us Times, led a meditation of Chenrezi, the bodhisattva of compassion. In the middle of the meditation, he instructed everyone to see Jerry as the bodhisattva, ‘merging with the lights of Buddha-mind in the journey through the bardos.”

Now, in the pre-millennium nineties, we may be seeing a generation who have steeped themselves in practice become inspired to take another, more mature, and more penetrating, look at psychedelics.

DURING THE SOPORIFIC FIFTIES, access to both psychedelics and Buddhism was limited to a small but influential elite. A British psychiatrist working in Canada, Dr. Humphrey Osmond. enlisted Aldous Huxley as a subject for his experiments with mescaline in Los Angeles one afternoon in the middle of May 1953. Huxley was well prepared. He and his fellow expatriate, the writer Gerald Heard, had studied Vedanta and practiced disciplined meditation for so me years, and Huxley had ransacked the world’s mystical writings for his anthology The Perennial Philosophy Sitting in his garden with Dr. Osmond, he experienced the grace and transfiguration he had read about. Remembering a koan from one of D. T. Suzuki’s essays, ‘What is the Dharma Body of the Buddha?” he found the answer: ‘The hedge at the bottom of the garden.” What had previously seemed “only a vaguely pregnant piece of nonsense” was now clear as day “Of course, the Dharma Body of the Buddha was the hedge at the bottom of the garden,” he reported in The Doors of Perception. ‘At the same time, and no less obviously, it was these flowers, it was anything that I, or rather the blessed Not I, released for a moment from my throttling embrace, cared to look at.” Of course Huxley still had his famous wits about him. ‘I am not so foolish as to equate what happens under the influence of mescaline . . . with the realization of the end and ultimate purpose of human life: Enlightenment.” he reassured his reader. “All I am suggesting is that the mescaline experience is what Catholic theologians call a gratuitous grace.’ not necessary to salvation but potentially helpful and to be accepted thankfully, if made available.” When Maria. Huxley’s wife of more than thirty years, lay dying of cancer he read to her the reminders from The Tibetan Book of the Dead, reducing them to their simplest form and repeating them close to her ear: ‘Let go, let go. Go forward into the light. Let yourself be carried into the light.” He continued after she had stopped breathing, “tears streaming down his face, with his quiet voice not breaking,” his son Matthew remembered.

A few years earlier, in July 1953, the ex banker ethnomycologist Gordon Wasson and his wife, Valentina, had reached the Mazatec village of Huautla de Jimenez, where they discovered the magic psilocybin mushrooms (teonanacatl, the ‘flesh of the gods”) and managed to take part in an all night velada. Wasson’s even handed and respectful article on his adventures was published by Life in 1957. The article was read by a Berkeley psychologist, Frank Barron, who had tried some of the mushrooms, and passed on his enthusiasm to another academic psychologist and old friend, Timothy Leary Before taking up his new job at Harvard’s Center for the Study of Personality Leary spent the summer in Cuemavaca. Naturally, he tried the mushrooms. “The journey lasted little over four hours,” he wrote. “Like almost everyone who had the veil drawn. I came back a changed man.”

Leary was now more interested in transcendence than personality assessment. As head of the Harvard Psychedelic Drug Research Project, he ran a session for MIT Professor Huston Smith, who made the experience available as a laboratory experiment for his seminars in mysticism. Next, in a now famous double blind experiment. On Good Friday in a chapel of the Boston University Cathedral. divinity students were given either psilocybin or a placebo. To no one’s surprise only those who had taken the psychedelic sacrament reported what appeared to be bona fide mystical experiences. Time published a favorable report, with reassuring quotes from Professor Walter Clark of Andover Smith, and other leading theologians. “We expected that every priest, minister, rabbi, theologian, philosopher, scholar and just plain God seeking man, woman and child in the country would follow up the implications of the study,” wrote Leary. Instead, “a tide of disapproval greeted the good news.” What followed was much worse. As use spread and the less expensive and much more powerful LSD became the drug of choice, all heaven and hell broke loose. Huxley, guest lecturing at MIT, advised discretion, keeping the drugs inside a small, charmed circle, a kind of aristocratic mystery school. Leary put forth a plan for training and certifying guides. But it was all too much, too fast, and too late. A generation gap had been blown open. The old were appalled, the young enthralled. “Some students quit school and pilgrimage eastward to study yoga on the Ganges,” Leary wrote in Flashbacks, “not necessarily a bad development from our point of view but understandably upsetting to parents. who did not send their kids to Harvard to become buddhas.”

Leary and Alpert left Harvard in 1963. Now they were but one wave, albeit a very visible and noisy one, in a counterculture transformation that had swept across America and crested in San Francisco. The center of activity was Haight Ashbury, which was just a short stroll from a Soto Zen mission, Sokoji, and its American offshoot, the San Francisco Zen Center But the spiritual atmosphere was more than Zen, it was eclectic, visionary, polytheistic, ecstatic and defiantly devotional. The newspaper of the new vision, The San Francisco Oracle, exploded in a vast rainbow that encompassed everything in one great Whitmanesque blaze of light and camaraderie. North American Indians, Shiva, Kali, Buddha, tarot, astrology, Saint Francis, Zen, and tantra all combined to sell fifty thousand copies on streets that were suddenly teeming with people. When the Oracle printed the Heart Sutra, it presented a double spread of the Zen Center version complete with Chinese characters, but also with a naked goddess, drawn in the best Avalon Ballroom psychedelic. While the beats had dressed in existential black and blue, this new generation wore plumage and beads and feathers worthy of the most flaming tropical birds. If the previous generation had been gloomy atheists attracted to Zen by iconoclastic directives, i.e., If you meet the Buddha, kill him, these new kids were, as Gary Snyder told Dom Aelred Graham in an interview in Kyoto, ‘unabashedly religious. They love to talk about God or Christ or Vishnu or Shiva.”

Snyder himself had gotten a firsthand look at the counterculture when he retimed from Japan for a short visit in 1966. He was just in time for the first Be In at Golden Gate Park, where he was joined by a number of friends from the early days. Allen Ginsberg was there, as were Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Michael McClure. Kerouac was conspicuous by his brooding absence. He wanted nothing to do with it all. (When Leary had offered him LSD back in Ginsberg’s apartment in New York he had objected: “Walking on water wasn’t built in a day.”) These new hippies horrified him. When a bunch of kids showed up at his mother’s house in Northampton, Long Island, with jackets that said “Dharma Bums” across the back, he slammed the door in their faces.

But now, at the Be In, with the sun shining through a deep blue sky and thousands of people at ease in all their finery on the meadow, Snyder read his poems and Ginsberg chanted the Heart Sutra to clear the meadows of lurking demons. Even Shunryu Suzuki Roshi of the burgeoning San Francisco Zen Center appeared briefly, holding a single flower.

Also present on the stage that afternoon were Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, the two ex Harvard psychology professors. who by now were prophetic psychedelic pied pipers. Whatever else LSD became in time, at that moment it was the messenger that led a fair number of people into the dazzling land of their own mind. What had begun as the private discovery of a few intellectuals and experimenters had spread in a flash. and for a split second of history it was as if the veil had been rent and all the archetypes of the unconscious now sprang forth.

There were those who claimed that psychedelics had changed the rules of the game, and that the mystic visions once enjoyed only by saints could now be had by anyone. In any case, it was obvious to the university researchers at Harvard, who had searched the scientific literature in vain, that the scriptures of Buddhism (and Hinduism) contained descriptions that matched what they had seen and felt. So Timothy Leary recast the verses of the Tao Te Ching in a book called Psychedelic Provers, and in 1962 Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert adapted the Bardo Thodol, The Tibetan Book of the Dead retranslated from Evans-Wentz’s Anglo-Buddhist to American Psychedelic” in The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Because the book was apparently meant to acquaint a dying person with the liberation of the Clear Light of Reality and then guide him or her through the peaceful and wrathful deities of the bardo it was fairly easy to recast it as a guide in which physical death was reconfigured as the death of the ego during a psychedelic trip. The Psychedelic Experience went through sixteen editions and was translated into seven languages.

One of the books most interested readers was Aldous Huxley, who called Leary from Los Angeles, where Huxley was now dying of cancer. When Leary flew our to see him. Huxley asked him to guide him through the bardos. Leary suggested that it would be better if Huxley’s second wife, Laura, guided the sessions. “No, I don’t want to put any more emotional pressure on her.’ Huxley replied. I plan to die during the trip, after all.’ In the end. Laura did give him the sacrament (LSD) and read him the instructions from the Tibetan Book of the Dead. And so Aldous Huxley passed peacefully into the Clear Light of Reality.

Before long, a number of the psychedelic luminaries made their way to India. In 1966. Ralph Metzner introduced Timothy Leary to the German born Lama Anagarika Govinda, who lived in Evans-Wentz’s old cottage in the Himalayan village of Nanital. “The lama had been most impressed to learn that The Psychedelic Experience contained a dedication to him.” Leary wrote in Flashbacks. Govinda had requested an LSD session which Metzner provided. For the first time, after thirty years of meditation, the lama had experienced the Bardo Thodal in its living sweating reality. According to Leary, Govinda told him that “many of the guardians of the old philosophic traditions had realized that the evolution of the human race had depended upon restoration of unity between the outer science advanced by the West and the inner yoga advanced by the East.” The teachings of Theosophy, Gurdjieff, Ramakrishna, Krishnamurti, and Evans-Wentz’s translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead had all been part of this plan. “You,” the lama told Leary, “are the predictable result of a strategy that has been unfolding for over fifty years. You have done exactly what the philosophers wanted done.” Presumably referring to Gerald Heard and Huxley, he said, “You were prepared discreetly by several Englishmen who were themselves agents of this process. You have been an unwitting tool of the great transformation of our age.

Ginsberg arrived in India that same year. Lately his psychedelic visions had become frightening, and he was wondering if he ought to continue. In Kalimpong he visited Dudjom Rinpoche, the great yogi scholar who was head of the Nyingma (Ancient Ones) lineage. “I have these terrible visions, what should I do?” he asked. Dudjom Rinpoche sucked air through his mouth, a traditional Tibetan sign of sympathy, and said, “If you see anything horrible, don’t cling to it; if you see anything beautiful, don’t cling to it.”

Leary’s partner, Richard Alpert (now known as Ram Dass), reached India in 1967, “hoping to find someone who might understand more about these substances than we did in the West.” When he met his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, Ram Dass gave him a hefty dose of nine hundred micrograms. “My reaction was one of shock mixed with the fascination of a social scientist, eager to see what would happen,” Ram Dass wrote.

“He allowed me to stay for an hour, and nothing happened. Nothing whatsoever He just laughed at me.”

Another time the old man swallowed a mind boggling twelve hundred micrograms. “And then he asked, ‘Have you got anything stronger?’ I didn’t. Then he said, ‘These medicines were used in Kulu Valley long ago. But yogis have lost that knowledge. They were used with fasting. Nobody knows how to take them now To take them with no effect, your mind must be firmly fixed on God. Others would be afraid to take. Many saints would not take this ‘And he left it at that ” (From Miracle of Love, Stories about Neem Keroli Baba, by Ram Dass.)