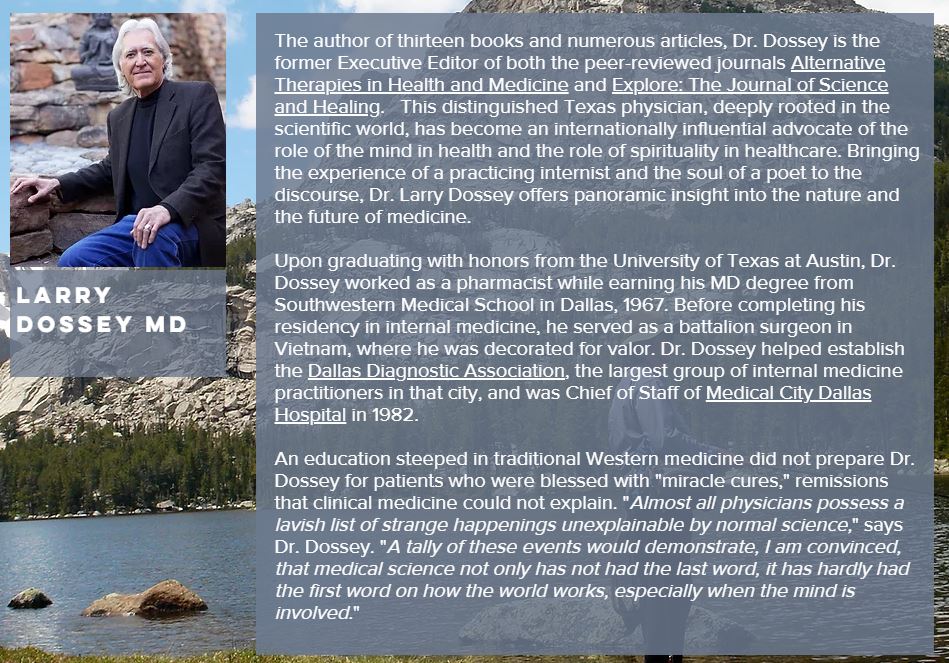

The following is a 1984 interview re-published with permissions from Larry Dossey, M.D.

(1984)

(1984)

See Larry Dossey website today

THE LAUGHING MAN: If you could formulate a goal for the medical profession, what would it be?

LARRY DOSSEY: The fundamental goal, in my judgment, ought to be to facilitate the spiritual evolution of the patient— specifically, to facilitate the felt oneness of body and mind. It should not be to prevent the stroke, heal the heart attack, or cure the cancer. All of that may indeed be possible, but if those things happen they should be viewed as a kind of grace. Cure should be regarded as a secondary issue. Consciousness, or spirit, should be viewed as the primary issue.

THE LAUGHING MAN: How do you define consciousness?

LARRY DOSSEY: My sense is that consciousness is an irreducible, fundamental aspect of the way things are. It is not contingent upon the material world, but it is certainly interrelated with the material world. To divide the world into two parts—material and unconscious and immaterial and conscious—is a distortion of the worst kind. Consciousness is a phenomenon that simply is, and one might say it leaves its tracks in matter.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Master Da Free John (Adi Da Samraj) (Adi Da Samraj) points out that the Eastern view is one of consciousness apart from objects, while the classical Western view is of a strictly material universe. But the highest realization is that there is no separation between consciousness and all that arises in it.

LARRY DOSSEY: I am very comfortable with those observations.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In Space, Time, and Medicine you make the point that on the material level, from the point of view of contemporary physics, there is no definitive separation between individuals. What about consciousness—do you consider human beings to have separate consciousnesses?

LARRY DOSSEY: I think the world is an indivisible unity and that each individual partakes of that wholeness. In that sense there is only one consciousness. But in medicine we don’t know how to communicate in a language that goes beyond the subject-object dichotomy. For instance, if a person drops dead from a heart attack after experiencing severe fright, we need to explain that outcome in terms of a limited aspect of consciousness. Such an explanation is unavoidable and we just have to bear in mind that it distorts what consciousness really is.

THE LAUGHING MAN: How is the unlimited view of consciousness practically useful in medicine?

LARRY DOSSEY: It releases us from the limitations of a strictly materialistic approach. You may remember that in Space, Time, and Medicine I referred to an experiment done with rabbits. They were all fed a diet high in fat, triglycerides, and cholesterol—in other words, the typical American fast-food diet. But one group was touched, petted, held, and talked to. That group was largely spared the ravages of coronary and arterial disease, while the other group was devastated by it.

If, instead of rabbits, you take men with high cholesterol levels, and you do such a simple thing as teach them to sit down and be quiet for fifteen minutes twice a day, their cholesterol levels fall in the magnitude of thirty percent. Such a simple practice only hints at what physiological changes might occur as one develops meditative skills, not to mention changes in one’s worldview. Commonly, that entire subject-object attitude of ordinary consciousness changes, replaced by a felt sense of one’s connectedness to the rest of existence. Another profound impact has to do with revising one’s notion about life and death. The concept of finality and of the importance of staying alive is replaced by the sense that there are no beginnings and endings; there is, rather, constant change in a universe that is in flux.

At any rate, getting back to the question of practical application, the translation of changes in consciousness into physiological changes is difficult to unravel. But there are certain discoveries associated with relaxation—such as the lower cholesterol I mentioned earlier, and also lower levels of adrenaline and cortisol. We can explain in reductionist fashion why these things happen, yet there is still that mysterious interface that nobody knows how to bridge. Scientifically, this area has barely been scratched.

THE LAUGHING MAN: It is much simpler if you are not scientifically inclined. You simply take it that love and meditation have positive effects on health and let it go at that

LARRY DOSSEY: Well, the game I am playing is, I admit, completely arbitrary. But I choose to play it this way in order to help the fields of medicine and biological sciences find something to latch on to. I am trying to make a persuasive case for the position that consciousness is an important factor in health.

THE LAUGHING man: How do you, as a physician, help the patient become aware that he is a process in space and time and not, as you say, an isolated entity?

LARRY DOSSEY: The average patient comes in with the classical Newtonian mechanistic worldview, stranded in linear time, moving towards death. My sense of how to guide him towards another perspective, after being involved in this kind of effort for almost two decades, is that it’s an ineffable process. I cannot formulate it in rigorous terms, but I know that it is possible and that it does occur. Even if I could tell you all about it, I’m not sure I would. I think there is a strong case to be made for the mysterious and indescribable.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Is it fair to say that there are two kinds of healers, those who deal with people incapable of jumping out of the mechanistic view and those who deal with people capable of making that leap?

LARRY DOSSEY: Yes. And there is an uncanny process in which those two kinds of healers and patients find each other. If you look at patient populations served by particular doctors, you can notice quite frequently that patients and physicians resemble each other in terms of behavior, attitudes, how they see the world.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Once a patient realizes he is part of an unlimited process, is there a role for the attitude of surrender?

LARRY DOSSEY: Absolutely. It is extraordinarily documentable in the biofeedback laboratory. There you see that the easiest way to sabotage success is to try hard; only through a sense of letting go can one achieve success.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In the real spiritual process, everything the disciple is holding on to in order to maintain his separate self-sense is challenged and undermined. Do you see illness serving that purpose?

LARRY DOSSEY: Most people enter illness within an egoic framework that requires conquering that specific illness, self-preservation at any cost. Yet, illness serves a great purpose when it deflates those egoic goals—it becomes a great teacher. That is why, I think, in some spiritual traditions it almost seems as if the practitioner courts illness, seemingly wishing to be tried by fire.

THE LAUGHING MAN: From the perspective of spiritual evolution, or the process of growth through stages, illness is seen as purification. Then, once the purification is complete, regeneration begins.

LARRY DOSSEY: Right, and for that reason we should be very leery of these presidential wars that are always being declared on specific diseases in order to totally eradicate them. I am not advocating disease, but in my new book, Beyond Illness, I have talked a lot about the inseparability of health and illness. Illness is a necessary element in our world for human growth and understanding. The notion of doing away with illness, which is often taken as the goal of medicine, would essentially be to do away with health as well. As Alan Watts said, there is the principle of “goes with”—one goes with the other—and they literally cannot be understood separately.

Perfect Enlightenment is perfect health.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Do you encounter people who are truly healthy?

LARRY DOSSEY: In my experience, they are extremely rare. But there is a Catch-22 here. People who are in a stable, harmonious condition under all circumstances rarely show up at physicians’ offices to announce their disposition. The average doctor thinks the entire population is a group of sick people with the outdated, mechanistic worldview, because those are the only people he ever sees.

Occasionally, however, I see patients moving beyond that mechanistic perspective in the context of illness—before my very eyes. Grave physical illness can be the progenitor of this transition, and that is when practicing medicine becomes a real joy. It is a spiritual change of a high degree, I think, and a splendid process to share with someone.

THE LAUGHING MAN: How would you define true health?

LARRY DOSSEY: I think the healthiest a person could be is when he or she is in what Da Free John (Adi Da Samraj) calls the seventh stage of life.

THE LAUGHING man: You would correlate physical health with spiritual Enlightenment?

LARRY DOSSEY: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. Perfect Enlightenment is perfect health. By that I do not mean that one is never physically sick, but that Enlightenment subsumes all the relativities we refer to as wellness and illness—functions of the flesh practically fall away into non-consideration, because highly advanced spirituality demonstrates superior physiological functioning.

It is for this reason that I do not think the medical and priestly functions can remain divorced. It seems unwise to me to farm out different regions of human functioning to narrow specialties. Eventually these arbitrary separations must fail, because there never was any separation in the first place.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In your book you related a delightful anecdote about a six-year-old boy, Mark, who discovered how to release nervousness through his feet. Would you say this was actual energy release?

LARRY DOSSEY: Mark was a pseudonym for a patient who came with a medical problem. In biofeedback therapy he learned to use breathing techniques in combination with imagery. During re laxation he would imagine that the problem was being released upon exhala tion through breathing holes in the soles of his feet. There is no known physiology to account for that. Nevertheless, I would entertain the notion that something like that actually did happen.

It is not safe to be physiologically dogmatic in medicine. We need only remember that less than a decade ago we roundly dismissed the idea that acupuncture could be anything more than a hoax. Now we have very scientifically acceptable physiological, as well as hormonal, ex planations of why what was thought to be impossible actually works.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace, Master Da Free John’s (Adi Da Samraj) book on health, he gives practical instructions for preparing for positive changes. He suggests beginning by releasing all negative conditions through the outside of your spine, the soles of your feet, or even all the parts of your body. Obviously, this young boy would make very effective use of such instructions.

LARRY DOSSEY: Exactly. And the fact that the instructions do not follow conventional physiological pathways makes no difference at all. Not having a scientific explanation is irrelevant—the measure is whether or not it works.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Don’t explanations often come after effectiveness is established?

LARRY DOSSEY: Very often. Breakthroughs often come accidentally or via a flash of intuition, and then the research goes on for years to explain why it works.

Speaking of research, there are some basic problems in medical research that we are not confronting. Practically all of medical research is flawed because of an erroneous assumption—namely, that we can replicate the initial conditions of an experiment and prove the results of the first experiment by repeating it. The physicist Eugene Wigner has pointed out that it is impossible to replicate the initial conditions of an experiment when you are dealing with conscious human beings. Conditions are always changing from experiment to experiment, if for no other reason than that no two people, and not even the same person at different times, bring the same consciousness to successive experiments. If the same people repeat the experiment, the initial conditions have changed if for no other reason than that they remember the experiment was done in the first place. Wigner’s insight points out the necessity for bringing consciousness into the experimental design.

In order to illustrate how failure to do this can create a massive problem in medicine, let me cite one example. In a group of ten thousand men who had heart disease, the incidence of angina— the pain associated with heart disease— was reduced by fifty percent in those who had loving spouses. Now suppose this group were used to judge the effects of a drug. You could give a placebo to those with loving spouses and it would appear to reduce angina by fifty percent. It would be hailed as an incredible breakthrough in the treatment of angina. Even a harmful drug that reduced the loving-spouse effect by half would appear to reduce angina by twenty-five percent and would be hailed as a breakthrough— twenty-five percent effective, while in fact being one hundred percent harmful.

Absurd as it may seem, studies are commonly conducted in this way. In no medical research are factors of consciousness, such as the felt support of love, accounted for. I think we may be sitting on some embarrassing therapeutic conclusions because medicine has not admitted to the potency of consciousness in health and illness. Potentially, it is an explosive issue. As things stand now, consciousness is considered to be either a non-factor, or a negative one, as in the old psychosomatic disease theory. But the angina study proves that consciousness can be an influence that is both enormous and positive.

THE LAUGHING man: Meditation and biofeedback are discussed in your book. Do you use them personally?

LARRY DOSSEY: I used to do biofeedback quite a lot, but as one gains skill in it one stops using the machine. At that point I’m not sure whether we should still call it biofeedback. At any rate, it is a quiet discipline I first used in medical school as personal therapy for headaches. Prior to that I had begun to meditate and as I took up biofeedback, it became clear that there is the strongest kind of corollary between the two, a great crossover in the states of consciousness occurring in them. In my mind, a crisp separation between biofeedback and meditation is impossible.

THE LAUGHING MAN: What do you think the fruits of those pursuits have been?

LARRY DOSSEY: One sequence of meditation led to an openness toward oriental teachings, preparing me for the literature of modern physics. Another fruit is probably the development of an intuitive sense about the way life works, an experiential approach rather than a strictly logical and discursive one. This is illustrated by the way Space, Time, and Medicine came about. I did not make a list of catchy ideas and then set about researching them. Rather, over time my worldview had developed, and I became aware of statements flowing from modem science that were coherent with my sense of things. There was the greatest kind of joy in seeing things come together.

THE LAUGHING MAN: You wrote about the anthropic principle in your book. Would you explain that briefly?

LARRY DOSSEY: The basic idea is that our being here and thinking the way we do places certain constraints on the evolution of the universe. There is, in other words, a strong correlation between the fact of our existence and what we perceive to be the state of existence.

TflE LAUGHING MAN: Master Da Free John (Adi Da Samraj) asserts that this physical universe is strictly an arbitrary product of consciousness. There are other universes, unavailable to our cognition or perhaps dreamlike, that are just as real.

LARRY DOSSEY: Yes, that is another way of stating the anthropic principle. It reminds me of Chuang Tzu’s aphorism about the man dreaming he was a butterfly. He awoke asking, “Am I a man dreaming I am a butterfly, or am I a butterfly dreaming I am a man?” A logical answer is elusive.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Why insist on an either-or logic? They are both true.

LARRY DOSSEY: I agree entirely. As long as you think those distinctions are mutually exclusive, you are always struggling to find out what is true.

THE LAUGHING MAN: The Way of Radical Understanding or Divine Ignorance is critical of that struggle. It is complete recognition of the egoic tendency to seek knowledge, whereas Enlightenment is not a matter of knowing anything more about anything. Ultimately, we do not know what anything is.

My feeling is that the messages of science during

this century have the most profound spiritual significance.

LARRY DOSSEY: Yes, if Enlightenment were a matter of knowledge, all the scholars would be Enlightened. If it were something to be attained, it would lie beyond the present, and if it did not include the present, it would be something other than the Ultimate and the Whole. There are inherent inconsistencies in the idea that one can attach any characteristics at all to the Ultimate. If it is given attributes, dualities are set up, one defines Spirit in terms of what it is not; then it becomes less than the Ultimate and Whole.

THE LAUGHING man: Yet, science is all about the search for knowledge. Is this compatible with a spiritual way of life?

LARRY DOSSEY: My feeling is that the messages of science during this century have the most profound spiritual significance. For the most part, though, mainstream scientists despise the idea of mixing science and values, ethics, or religion.

THE LAUGHING MAN: The notion that science can serve spiritual life is also despised by many religious people.

LARRY DOSSEY: Yes, because of the profoundly distorted idea about what science is. Even most scientists still entertain the classical view that the world is out there, we are separate from it, time is linear—all the old mechanistic concepts.

THE LAUGHING MAN: The few scientists who are not subject to the classical limitations are the sources of everything remarkable and wonderful about modem science.

LARRY DOSSEY: Yes, and also frequently under fire from the establishment for their views—people like Eugene Wigner, who is severely criticized for suggesting that consciousness must be considered in physics. John Wheeler, who hypothesized the existence of black holes, was accused of being senile. Even Einstein, when he began to talk about God and the mystical qualities of the world, was accused of being senile.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Have you written about the primacy of consciousness in human health in your new book?

LARRY DOSSEY: Since my first book, my primary thrust has been to question exactly what health and illness are, how they interrelate, and what role they play in the evolution of human lives.

If you look at illness from an evolutionary point of view, I think we owe our existence as a species to the occurrence of illness periodically down through the ages. Our immune system evolved due to encounters with offending agents, accompanied by many casualties along the way. In other areas of science we see the idea that chaos is the progenitor of order. Parallel to that is this idea that illness is the progenitor of health.

THE LAUGHING MAN: How might this change the attitude of the healer?

LARRY DOSSEY: I think basically we can say that healing is an illusion. There is a deep and profound sense in which health and illness, like mind and matter, are unified in what Bohm calls the implicate domain. We flatter ourselves as healers if we think we can really set things right. There is this seriousness about ourselves that is especially misplaced in healing endeavors. It is based, at least in part, on the failure to understand that at some crucial level, health and illness come together and that they partake of a common reality. ■