|

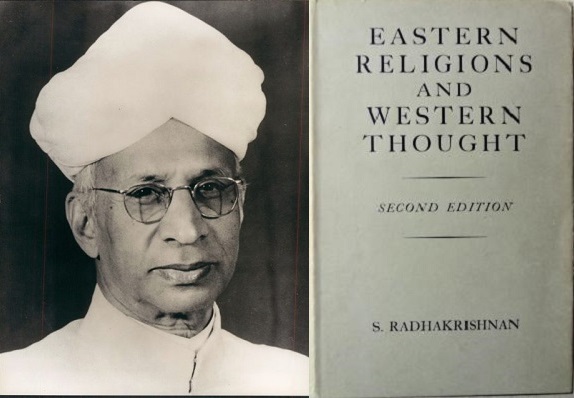

S. Radhakrishnan – Eastern Religions and Western Thought Lectures Given in 1936-1938 |

p. 252

Chapter VII

GREECE, PALESTINE, AND INDIA

![]() O what is this phenomenon of spiritual waywardness in the West due ? May it not be that it is motived by a deep instinct for self-preservation and a longing for world unity? The attraction of Eastern forms is probably due to a failure of nerve akin to what occurred at the bcgijining of the Christian era, which experienced a similar phenomenon. We seem to be vaguely aware that in spite of our brilliant and heroic achievements wc have lost our hold on the primal verities.

O what is this phenomenon of spiritual waywardness in the West due ? May it not be that it is motived by a deep instinct for self-preservation and a longing for world unity? The attraction of Eastern forms is probably due to a failure of nerve akin to what occurred at the bcgijining of the Christian era, which experienced a similar phenomenon. We seem to be vaguely aware that in spite of our brilliant and heroic achievements wc have lost our hold on the primal verities.

The instability of life is manifesting itself in many forms. The affirmation of the sovereign State, owing allegiance to none and free to destroy its fellows, itself open to a similar fate without appeal, racial and national iaolatries which deny the corporate life of the whole, the growing tyranny of wealth, the conflict between rich and poor, and the destruction of the co-operative spirit threaten the very existence of society. Insecurity of nations and destitution of peoples have always been with us, but periodic sanguinary upheavals have also been with us. The two are different sides of a social order which is really primitive in character. Greek culture was born in strife, in strife of city-States and against foreign foes.

The Roman Empire was

formed by a series of destructive and often savage wars,

though it became the home and cradle of Western civilixation. The period of the Middle Ages, when Europe had the

formal unity of a common religion, was also the period of

the most incessant war, It will not be an over-statement to

say that never a day passes but the Great Powers are engaged

in wars small or great in some part of their vast dominions.

Even now we have the struggle within for juster and better

conditions of life, and without for independence. Man has

not grown worse, In some points he is an improvement on

his predecessors, but we need not exult in it.

p. 253

When Mrs.

Rosita Forbes (Mrs. Col McGrath) rvisited the penitentiary at Sao Paulo she asked

if there were many thieves among the inmates. The warden was shocked. * 0h, no,’ he replied, ‘Brazilians are very

honest. Nearly all these men are murderers.’

Augustine

quotes with approval the reply of the pirate to Alexander

the Great, ‘Because I do it with a littfe ship, I am called

a robber, and you because you do it with a great fleet, arc

called an emperor. The final test of every social system is

the happiness and well-being of men and women.

Those

who live for economic power and for the State are not concerned with the development of a true quality of life for the

people and arc obliged to adopt war as a national industry,

Our habits of mind and our relations to our neighbours have

not altered much, but the mutual antagonisms and reciprocal

incomprehensions are turning out most dangerous in a

closely knit world with new weapons of destruction. Enormous mechanical progress with spiritual crudity, the love of

economic power, and political reaction, with all the injustice

that it involves, have suddenly startled us out of our complacency.

We are asking ourselves whether the props by

which society has hitherto maintained itself precariously arc

moral at all, whether the present order with its slave basis of

society and petty particularism is based on canons of justice,

When universsd covetousness has outstripped the means

of gratifying it; when the unnatural conditions of life demand for their defence the conversion of whole nations into

mechanized armies; when the supremacy of power-politics

is threatened by its own inherent destructiveness; when the

common people feel in their depths blessed are the wombs

which never bare, the breasts that never gave suck’; it is a

challenge to our principles and our faith. The perception

of the tr^ic humiliation of mankind must make \is think

deeply.

The world is a moral Invalid surrounded by quacks

and charlatans, witch-doctors and medicine men who are interested in keeping the patient in the bad habits of centuries.

The patient requires drastic treatment. His mind must be

led out of the moulds in which it has been congesting and

set free to think in a wider ether than before. Ultimate reality

cannot be destroyed. Moral laws cannot be mocked.

p. 254

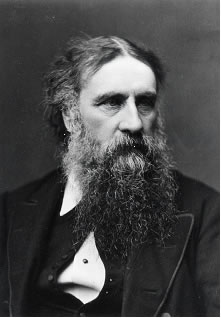

George

Macdonald has a parable In which a strong wind tried to blow

out the moon, but at the end of it all she remained ‘motionless miles above the air’, unconscious even that there had been a tempest. It is because we have not developed the spiritual

equipment to face facts and initiate policies based on truth

and tolerance that we have to secure our injustices by the

strength of arms. The alternatives are either a policy of

righteousness and a just reorganization of the world or an

armed world. That is the issue before us. It is of the utmost

seriousness and greatest urgency, for it is even now upon us.

It is a fact of History that civilizations which are based on

truly religious forces such as endurance, suffering, passive

resistance, understanding, tolerance are long-lived, while

those which take their stand exclusively on humanist elements like active reason, power, aggression, progress make

for a brilliant display but are short-lived.

Compare the

relatively long record of China and of India with the eight

hundred years or less of the Greeks, the nine hundred years

on a most generous estimate of the Romans, and the thousand

years of Byzantium. In spite of her great contributions of

democracy, individual freedom, intdleccual integrity, the

Greek civilization passed away as the Greeks could not combine even among themselves on account of their loyalty to

the city-Scates. Their exalted conceptions were not effective

forces, and, except those who were brought under the mystery

religions, the Greeks never developed a conception of human

society in spite of the very valuable contributions of Plato,

Aristotle, and the Stoics. The Roman gifts to civilization

are of outstanding value, but the structure of the Empire

of Rome had completely ceased to exist by a.d. 500.

Empires have a tendency to deprive us of our soul. Extension

in space is not necessarily a growth in spirit. Peace prevailed

under the Roman rule, for none was left strong enough to

oppose it. Rome had conquered the world, and had no rival,

none to struggle with or struggle for. The fax Romana reigned, but it was the peace of the desert, of sullen acquiescence and pathetic enslavement. The cement of the whole

structure was the army. The head of the army was the head

of the State, the Imperator, answering to our ‘Emperor’. In

the middle of the third century all manner of upstart soldiers

who were able to gather a few followers took over the

governments, each in his own region and over his own

troops. With the weakening of the Imperial government, moral anarchy increased. With the raids of pirates on the

coast and of marauding bands on the frontiers, insecurity

was rife. At the end of the third century, Diocletian attempted a reorganization of the whole State, but nothing

could arrest the decline in standards.

p. 255

There are some scholars of the Renaissance who attribute

the fall of Rome to the spread of the ‘superstition’ of Chris-

tianity, thus echoing the cry of the Chronicler of the pagan

reaction under Julian the Apostate, ‘The Christians to whom

we owe all our misfortunes . . ” Possibly the appeal of

Christianity grew stronger as outward fortunes sank lower.

The fall of Rome is not to be explained solely by the barbarian invasions. Treason from within was its cause quite

as much as danger from without.^ Greed and corruption,

growth of vast fortunes and preponderance of slaves threw

society out of balance. It was a period of disorder, the collapse of the higher intellectual life and the decline of

righteousness. European civilization had fallen so low that

many thought that the end of the world was near.

‘The

whole world groaned at the fall of Rome’, said Augustine.

‘The human race is included in the ruin ; my tongue cleaves to

the roof of my mouth and sobs choke my words to think that

the city is a captive which led captive the whole world’, wrote

St. Jerome from his monastery at Bethlehem. To Christian

and pagan alike it seemed that the impossible, the unthinkable, had happened. Rome, the dispenser of destiny, the

eternal city whose dominion was to have lasted for ever, fell.

The Empire was broken up into two parts, the Western

with Rome for its capital and the Eastern with Constantinople. By the end of the fifth century the whole of western

and north-western Europe was in the hands of the barbarians.

Italy had fallen to the Ostrogoths; Gaul and a large part of what is now Germany to the Franks; northern Africa to the

Vandals; and Spain to the Visigoths.

1. M. Renan says that ‘Christianity was a vampire which sucked the life-

blood of ancient society and produced that state of general enervation against

which patriotic emperors struggled in vain’ {Marc Aurih^ p. 589).

2 Mr, Stanley Casson writes: ‘The barbarian intrusions were more the

consequence than the cause of her sickness. What had happened was that

standards had fallen. Elements wholly alien to Roman rule and Roman freedom had emerged. In the letters of Sidonius we hear of censorship, of political

murder disguised as accident, of bribery and corruption in high places, and

evien of the persecution cf the Jews’ {Progress and Catastrophe p. 203),

p. 256

The Eastern Empire

was called the Byzantine, as its capital, Constantinople, was

founded by Constantine on the site of the ancient Byzantium, a town formed by nature to be the centre of a great

empire. From its seven hills it commanded the approaches

to both Europe and Asia. Its narrow straits joined East

and West. In all this darkness the single ray of light which

remained to kindle civilization once again was preserved

within the narrow walls of Byzantium. Theodosius built the

great fortress, and Justinian, who succeeded him, rebuilt its

institutions. But the fear of attack by barbaric hordes from

every part of the world was constantly present,^ and the

values of spirit could not be fostered in an atmosphere of

constant fear and imminent catastrophe. Philosophy failed,

literature languished, and religion became rigid and superstitious.

Before Byzantium fell to the Turks in a.d. 1453

she had succeeded in spreading in the Western world the

light of civilization and culture derived from Greece and

Rome. And modern civilization, which took its rise after

the fall of Byzantium, seems to have worked itself out, for

it is exhibiting today all the features which are strangely

similar to the symptoms which accompany the fall of civilizations: the disappearance of tolerance and of justice; the

insensibility to suffering; love of ease and comfort, and

selfishness of individuals and groups; the rise of strange

cults which exploit not so much the stupidity of man as his

unwillingness to use his intellectual powers; the wanton

segregation of men into groups based on blood and soil.

A world bristling with armaments and gigantic intolerances,

where all men, women, and children are so obsessed by the

imminence of the catastrophe that streets are provided with

underground refuges, that private houses are equipped with

gas-proof rooms, that citizens are instructed in the use of

gas-masks, is conclusive evidence of the general degradation. Through sheer wickedness, by advocating disruptive

forces, not co-operative measures, by allegiance to the ideals of power and profit, man is preparing to destroy even the

little that his patient ingenuity has built up. Instead of progress in charity we have increase of hostilities. In order to

live we seem to have lost the reason for living. World peace

is a wild dream, and modern civilization is not worth saving

if it continues on its present foundations.

There were attacks by the Persians and the Arabs in a.d. 616, 675,

717, b7 the Bulgarians in a.d. 813, b7 the Russians in a.d. 866, 904, 936,

1043.

p. 257

The Chinese and the Hindu civilizations are not great in

the high qualities which have made the youthful nations of

the West the dynamic force they have been on the arena

of world history, the qualities of ambition and adventure, of

nobility and courage, of public spirit and social enthusiasm.

We do not find their people frequently among those who risk

their lives in scientific research, who litter the track to the

North or the South Pole, who discover continents, break records, climb mountain heights, and explore unknown regions

of the earth’s surface. But they have lived long, faced many

crises, and preserved their identity. The fact of their age

suggests that they seem to have a sound instinct for life, a

strange vitality, a staying power which has enabled them to

adjust themselves to social, political, and economic changes,

which might have meant ruin to less robust civilizations.

India, for example, has endured centuries of war and invasion, pestilence, and human misrule. Perhaps one needs a

good deal of suffering and sorrow to learn a little understanding and tolerance. On the whole, the Eastern civilizations are interested not so much in improving the actual

conditions as in making the best of this imperfect world, in

developing the qualities of cheerfulness and contentment,

patience and endurance. They are not happy in the prospect

of combat. To desire little, to quench the eternal fires, has

been their aim. ‘To be gentle is to be invincible’ (Lao Tze).

The needs of life are much fewer than most people suppose.

If the Eastern people aim at existence simplified and self-

sufficient and beyond the reach of fate, if they wish to develop gentle manners which are inconsistent with inveterate

hatreds, we need not look upon them as tepid, anaemic folk,

who are eager to retreat into darkness. While the Western

races crave for freedom even at the price of conflict, the

Easterns stoop to peace even at the price of subjection. They

turn their limitations into virtues and adore the man of few longings as the most happy being.

Diogenes annoyed

Plato with the taunt that if he had learned to live on rough

vegetables he would not have needed to flatter despots. The

future is hidden from us, but the past warns us that the

world in the end belongs to the unworldly.

A spiritual

attitude to life has nourished the Eastern cultures and given

them an unfailing trust in life and a robust common sense

in looking at its myriad changes. A purely humanist civilization, with its more military and forceful mode of life like

the modern, faced by the risk of annihilation, is turning

to the East in a mood of disenchantment.

In Greek mythology, young Icarus was made to fly too high until the wax

of his wings melted and he fell into the sea, while Daedalus,

the old father, flew low but flew safely home. This is not

a mere whim. The qualities associated with the Eastern

cultures make for life and stability; those characteristic of

the West for progress and adventure.

The Eastern civilizations are by no means self-sufficient.

They seem today to be chaotic, helpless, and incapable of

pulling themselves together and forging ahead. Their peoples,

unpractical and inefficient, are wandering in their own lands

lost arid half-alive, with an old-fashioned faith in the triumph

of right over might. They suffer from weaknesses which

are the symptoms of age, if not senility. Their present listless

and disorganized condition is not due to their love of peace

and humanity but is the direct outcome of their sad failure

to pay the price for defending them. What they have gained

in insight they seem to have lost in power. They require to

be rejuvenated. So much goodness and constructive endeavour are lost to the world by our partial philosophies of

life.

If modern civilization, which is so brilliant and heroic,

becomes also tolerant and humane, a little more under-

standing, and a little less self-seeking, it will be the greatest

achievement of history.

East and West are both moving out of their historical

past towards a way of thinking which shall eventually be

shared in common by all mankind even as the material

appliances are. We can speak across continents, we can

bottle up music for reproduction when desired, animate

photographic pictures with life and motion; but these do not touch the foundations of culture, the general configuration of life and mind.

These are cast in the old moulds

which have never been broken, though new materials have

been poured into them. They are now beginning to crack.

The rifts which first made their appearance decades ago

have now become yawning fissures. With the cracking of

the moulds, civilization itself is cracking. Further growth

in the old moulds is not possible. We need to-day a proper

orientation, literally the values the world derived from the

Orient, the truths of inner life. They are as essential for

human happiness as outer organization. The restlessness

and self-assertion of our civilization are the evidence of its

youth, rawness, and immaturity. With its coming of age,

they will wear off. The fate of the human race hangs on

a rapid assimilation of the qualities associated with the mystic

religions of the East. The stage is set for such a process.

Till this era, the world was a large place, and its peoples

lived in isolated comers. Lack of established trade-routes

and means of communication and transportation and primi-

tive economic development helped to foster an attitude of

hostility to strangers, especially those of another race. There

has not, therefore, been one continuous stream into which

the whole body of human civilization entered. We had a

number of independent sprin|;s, and the flow was not con-

tinuous. Some springs had dried up without passing on any

of their waters to the main stream. To-day the whole world

is in fusion and all is in motion. East and West are fertilizing

each other, not for the first time. May we not strive for

a philosophy which will combine the best of European

humanism and Asiatic religion, a philosophy profounder and

more living than either, endowed with greater spiritual and

ethical force, which will conquer the hearts of men and com-

pel peoples to acknowledge its sway.?

II

It may be asked whether Western civilization is not also based on religious values. Greek art and culture, Roman law and organization, Christian religion and ethics, and scientific enlightenment are sid to be the mouulding foreces of modern civilization. It will be useful if we consider the exact nature of the religious life of the West and the extent

of its influence on Western civilization.

At the risk of over-

simplification, which is inevitable when we describe the

development of centuries in a few paragraphs, it may be

said that in the Western religious tradition three currents

which frequently cross and re-cross can be traced. We may

describe them for the sake of convenience as the Graeco-

Roman, the Hebrew, and the Indian.

The Graeco-Roman has for its chief elements rationalism,

humanism, and the sovereignty of the State. The spirit of

speculation which questioned religious ideas and sought to

follow truth regardless of the discomfort it might cause us

started with the Greeks. Xenophanes fought hard to emancipate his people from superstition and lies. He preached

against belief in gods who could commit acts which would

be a disgrace to the worst of men. Democritus found the

self-existent in the atom and Heraclitus in fire. The latter

said: ‘The world was made neither by one of the gods nor

by man ; and it was, is and ever shall be an ever-living fire,

in due measure self-enkindled and in due measure self-

extinguished.’ Nothing is, everything is becoming.

For

Protagoras, man is the measure of all things, and as for God,

He cannot be found even if He exists. He says : ‘Concerning

the gods I can say nothing, neither that they exist nor that

they do not exist; nor of what form they are; because there

are many things which prevent one from knowing that,

namely, both the uncertainty of the matter and the shortness

of man’s life.’

For Critias, “nothing is certain except that

birth leads to death and that life cannot escape ruin”. According to Gorgias, every man was free to fix his own

standard of truth. Unless Plato is wholly unfair, certain of

the Sophists were prepared to justify philosophically the

doctrine that might is right. The orthodox suspected even

Socrates and accused him of impiety and corrupting the

youth of Athens. Doubts run through the poetry of Euripides, the rationalism of the Stoics, the schools of the

sceptics, and the materialism of the Epicureans. In spite of

a different tendency, both the Stoics and the Epicureans

adopted physical explanations of the universe. They treated

the world, including man’s soul, as something material.

Epicurus revived the atomic view of Democritus. He aimed

at constructing a world on scientific principles to free men’s

minds from fear of the gods and the evils of superstition.

Man’s soul at death dissolves again into the atoms which

made it. He conceded to popular beliefs when he admitted

the existence of the gods, but they did nothing except serve

as models of ideal felicity. They are indifferent to human

affairs and so prayers to them are futile. Faith in gods could

not last when gods were being made before men’s eyes.

The

Ptolemies of Alexandria were freely spoken of as gods. In

an inscription at Calchis as early as 196 b.c. Quinctius

Flamininus was associated in inscriptions with Zeus,

Apollo, Heracles, and the personified Roma. Julius Caesar

received divine honours even in his life; and the day after

his death, the Senate decreed that he should be treated as a

god; in 44 b.c. a law was passed assigning him the title of

divus and the great Augustus dedicated in 29 b.c. the new

temple of Divus Julius in the Forum.* All this confirmed

the scepticism of Euhemerus that the gods were only great

men deified.

Though classical Rome was far less speculative than

Greece, it produced one of the greatest sceptics of antiquity,

Lucretius. With the fervour of a religious enthusiast he

attacked religion and hurled defiance and contempt on it.

Through his poem De Rerum Natura he tried to free men’s

minds from the fears which beset and haunted them. He

accustomed men to the idea of complete annihilation after

death. In the early days of the Roman Empire even such an

austere Stoic as Marcus Aurelius looked upon the Chris-

tian religion with fear and contempt. Independent thought

was efficiently suppressed by the tyranny of the Church till the

period of the Renaissance, though in the thirteenth century

the Emperor Frederick II declared, if the story be true,

that the world had been deceived by three impostors, Moses, .

Jesus, and Mohammad. Roger Bacon was a definitely

sceptical thinker. Machiavelli in his Prince revived the old

conception that religion is an instrument for keeping the

people in subjection. He did not disguise his intense dislike

of Christianity. Rabelais (1690) was impatient with asceticism and conventional religion.

* See Cyril Bailey, Phases in the Religion of Ancient Rome (1932)1

pp. 138-40.

Science in the Middle Ages

was largely occultism and magic; nature was full of spirits

and to meddle with it was to risk damnation. Friar Bacon

was imprisoned as a sorcerer. The scientific movement of

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with such names as

those of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Harvey, and Newton,

discouraged the supernatural explanations of natural phenomena and led to the conception of the universe as a great

machine working by rigidly determined laws of causation.

The thrill of new discoveries and mental activities raised

great expectations. Men seemed to be on the eve of surprising the last secrets of the universe and building a stately fabric of enduring civilization. They seemed to become the

Lords of creation, though not the heirs of heaven. While

some of the leading representatives of the scientific movement, like Descartes and Boyle, Bacon and Newton, were not

anti-religious, the movement as a whole encouraged free

thinking.

The religious conflicts which followed the Reformation contributed to the growth of scepticism and wars.

The Church was split up into a number of sects and disputes; persecutions and wars became more frequent. Montaigne (1533-92) was nominally a Catholic but was really

an Agnostic. He says; ‘Death is no concern of yours either

dead or alive: alive because you still are\ dead because you

are no longer.’ Leonardo da Vinci rejected every dogma

that could not be tested and was a complete sceptic. Shakespeare was no better. J. R. Green writes: ‘The riddle of

life and death he leaves a riddle to the last, without heeding

the theological conclusions around him.’ For Francis Bacon ‘the mysteries of the Deity, of the Creation, of the Redemption’ are ‘grounded only upon the word and oracle of Grod,

and not upon the light of nature’.^ Hobbes’s scorn of super-

naturalism and revealed religon is undisguised. All that we

can legitimately say of God is that He is the unknown cause

of the natural world, and so our highest duty consists in

implicit obedience to the civil law. He reduced religion to

a department of State and held that the sovereign power was

absolute and irresponsible.* Locke defended theism more on pragmatic grounds. It was necessary for social security.

* Advancement of Learning, \i. * See further, p. 388.

His

work on The Reasonableness of Christianity aims at proving

that the tenets of the Christian religion are in accordance

with reason. It is assumed that their rationality is what

makes them worthy of acceptance. So for him reason is a

completely reliable source of knowledge and an infallible

guide in the quest for certainty. But the materials on which

reason works are provided not in a rational intuition which

penetrates into real being but in sensation and reflection on

sense data. If these are the only material for knowledge, it

follows that religious truths lie beyond the scope of man’s

reason. Locke admits the reality of revealed knowledge,

though he himself would prefer rational knowledge even in

the realm of religion. He believes that the central concep-

tions of religion can all be proved rationally.^ Toland,

Locke’s young Irish disciple, defends the deistic position

and finds support for it in the Gospels.^ ‘All men will own

the verity I defend if they read the sacred writings with that

equity and attention that is due to mere humane works, nor

is there any different rule to be followed in the interpretations of scripture from what is common to all other books.’

The Deists contend that all the truths necessary for a religious life could be gained rationally and such a natural

religion is the only one worthy of the respect of men. ‘All

the duties of the Christian religion’, says Archbishop Tillotson, ‘which respect God, are no other but what natural light

prompts men to, excepting the two sacraments, and praying

to God in the name and by the mediation of Christ.’ ‘And

even these’, Anthony Collins observes, ‘are of less moment

than any of those parts of religion which in their own nature

tend to the Happiness of human Society‘. We cannot be

sure that Christianity is a revealed religion, when no one

seems to know what is revealed or perhaps everybody seems

to know that his own version of the faith is the true revelation and everything else a deadly error.

Since the precepts of natural religion are plain, and very intelligible to all

mankind, and seldom seem to be controverted; and other revealed traths which

are conveyed to us by books and languages, are liable to the common and

natural obscurities and difficulties incident to words: methinks it would be-

come us to be more careful and diligent in observing the former, and less

magisterial, positive and imperious in imposing our own sense and interpreta-

tions on the latter’ {Essay Concerning Human Understanding, m. k. 23).

* Christianity not Mysterious, ii. iii. 22 (1696).

3 Discourse of Free-thinking {I’ji’i’jt’p. 136.

The fact that the

Bible is an inspired document has not prevented its official

interpreters from disagreeing on all fundamentals. Deism

developed, and the Deists are rationalists with a feeling for

religion. Their rationalism took them away from orthodoxy

and their religion kept them from atheism. According to

some seventeenth-century Nonconformists a clergyman

answered their demand for the scripture texts on which

the Thirty-nine Articles were based by quoting 2 Timothy

iv. 1 3 : ‘The cloak I left at Troas, . . . bring with thee, and

the books, but especially the parchments.’ If Timothy had

not been remiss in executing St. Paul’s command we would

have had the parchments which provided the missing

authority. When Anthony Collins was asked why, holding

deistical opinions, he sent his servants to churches, he answered: ‘That they may neither rob nor murder me!’

Lord

Bolingbroke considered Christianity a ‘fable’, but held that

a statesman ought to profess the doctrines of the Church

of England.* Thomas Woolston in his six Discourses on the

Miracles of Christ (1727-9) maintained that the Gospel narratives were a ‘tissue of absurdities’. Hume declared that

miracles were impossible and accepted arguments for the

existence of God were untenable. Baron d’Holbach stood

for a materialistic conception of the universe and denied the

existence of God and the immortality of the soul. Voltaire,

Mr. Noyes tells us, was a theist, but there is no doubt that

he was a bitter critic of the Church, which he looked upon

as the instigator of cruelty, injustice, and inequality. Look

at his prayer which breathes the humanitarianism of the

French enlightenment: ‘Thou hast not given us a heart that we may hate one another, nor

hands that we may strangle one another, but that we may help each

other to bear the burden of a wearisome and transitory life; that the

small distinctions in the dress which covers our weak bodies, in our inadequate languages, in our absurd usages, in all our imperfect laws,

in all our senseless opinions, in all our social grades, which to our eyes

are so different and to thine so alike, that all the fine shades which

dififerentiate the “atoms” called “men” may not be occasions for hate

and persecution.’

Leslie Stephen in his English Thought in the Eighteenth Century writes,

referring to the later Deistic period: ‘Scepticism widely diffused through the

upper classes, was of the indolent variety, implying a perfect willingness that

the Churches should survive though the Faith should perish’ (vol. i, p. 375).

He was certainly not an orthodox churchman. During an

illness towards the close of his life he was visited by a priest,

who summoned him to confession. ‘From whom do you

come ?* inquired the sick man. ‘From God’, was the reply.

When Voltaire desired to see his visitor’s credentials, the

priest could go no farther and withdrew.

Diderot and the

Encyclopaedists had unqualified contempt for conventional

religion. Diderot cried out at the end of his Interpretation

oj Nature : ‘O God, I ask nothing from Thee; if Thou art not, the course of

nature is an inner necessity; and if Thou art, it is Thy command;

O God, I know not whether Thou art, but I will think as though

Thou didst look into my soul, I will ask as though I stood in Thy

presence. … If I am good and kind, what does it matter to any

fellow creatures whether I am such because of a happy constitution

or by the free act of my own will or by the help of Thy Grace ?’

There is little in common between Rousseau’s sentimental

theism and Christian orthodoxy. Leibniz rejoiced in the

‘religion without revelation’ of China. Kant tells us that

there can be no theoretical demonstration of the existence of

God, though we need Him for practical life. Hegelian

dialectics have no place for a God to whom we can pray and

offer worship. The Prussian State was for him ‘the incarnation of the divine idea as it exists on earth’. National Socialism continues the Hegelian tradition and looks upon, not

the Prussian State, but the Nordic race, as the ultimate and

noblest self-expression of the cosmic intelligence. Its official

philosopher, Herr Rosenberg, in his book on The Myth of

the Twentieth Century (1930), makes it clear that he has no

faith in the transcendent God of the theist. His deity is the

human spirit and the racial society. Fichte in his Addresses

to the German Nation developed at length the notion of an

‘elect race’. His doctrine is continued in the work of Gobineau and his well-known theory of the inequality of human

races. In Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s Foundations of the 19th Century the racialist legends reappears in a psyeudo-scientific setting.

Rosenberg’s Myth is the classic on the

question. Each race has its particular soul in which its most

intimate being is expressed. Its special virtues are regarded

as the specific qualities of the blood. The human species is

an abstraction : we have only a number of races determined

by differences in the hereditary composition of the blood.

Human races are not only diverse but of unequal value. The

superior race is the Nordic. Its branches are to be recognized in the Amorites of Egypt, the Aryans of India, the

Greeks of the early period, in the ancient Romans, and above

all in all the Germanic peoples, whose chief representatives

are the Germans. The spirit of this race is personified in

the god Wotan, who embodies their spiritual energies. Con-

tamination with inferior races is the great danger which

menaces the superior race in all periods of universal history.

India and Persia, Greece and Rome are witnesses to the process of racial degeneration. A religion of universalism is

foreign to the Nordic race. Catholic religion. Freemasonry,

Communism are the enemies of Nordic; superiority. The

Germanic soul will be manifested in the Third Reich with

the symbol of the Swastika in place of the Cross. The aim

of the National Socialist Party is to rescue from contamination and develop this precious Nordic element,

Lessing conceives the whole religious history of mankind

as an experiment of divine pedagogy. He declares that accidental historical truths can never be the evidence for eternal

and necessary rational truths. Hamann observes that Kant’s

moralism meant the deification of the human will and Lessing’s rationalism the deification of man’s reason. Nietzsche

drew a distinction between the morality of masters and that

of slaves. The Romans are for him the strong and the whole,

the aristocratic and the noble. Christianity is the moral

rebellion of the slaves based upon the resentment of the

weak against the strong. Their victory over Rome was the

victory of the sick over the healthy, of the slaves over

the noble. Out of a feeling of resentment the slave decided

to be the first in the Kingdom of Heaven. Auguste Comte

put Humanity in the place occupied by God. A morality of

service in a godless universe is the ideal of the positivists.

G. H. Romanes (1848—94) in his A Candid Examination of

Theism writes : ‘It is with the utmost sorrow that I find myself

compelled to accept the conclusions here worked out: I am

not ashamed to confess that, with the virtual negation of God,

the universe has lost to me its soul of loveliness.’ He later

abandoned this position.^ Even the Christian thinkers themselves tried to reinterpret Christianity. Schleiermacher reduced religion to a feeling of dependence on God. Ritschl

meant by redemption the belief that God has revealed an ideal

for man to work towards.* To many Christians their religion

meant only love of man and unselfish service, Even though

the orthodox may use the old terminology of grace, communion, and redemption, they stress only pure morality or

humanitarian ethics. The works of Strauss and Renan, Karl

Marx and Nietzsche, and the scientific doctrines of evolution

have made atheism popular. A general tendency to irreligion

is in the air. Unbelief is aggressive and ubiquitous.

The strain of scepticism has been a persistent feature of the

Western mind. It takes many forms, modernism in religion,

scientific humanism, or naturalism. Modernism is not confined to movements which assume that name. All those who

wish at the same time to be traditionally religious and rational-minded are modernists in different degrees. In the Introduction to the Report of the Commission on Christian Doctrine

in the Church of England the- Archbishop of York writes : ‘In view of my own responsibility in the Church I think it right

here to affirm that I wholeheartedly accept as historical Acts the Birth

of our Lord from a Virgin Mother and the Resurrection of his physical

body from death and the tomb. But I fully recognise the position of

those who sincerely affirm the reality of our Lord’s Incarnation without accepting one or both of these two events as actual historical

occurrences, regarding the records rather as parables than as history,

a presentation of spiritual truth in narrative form.’* What we accept of revelation depends on our piety and

intellectual conscience. The issue, however, relates not to this or that item of belief but the way in which any part of

the content of religion is arrived at and justified. It is not

a question of the articles of belief but of the intellectual habits

and methods.

See p. 389.

* ‘By the Kingdom’, according to Dr. A. E. Garvie, Ritschl means ‘the

moral ideal for the realization of which the members of the community bind

themselves to one another by a definite mode of reciprocal action’ {Encyclo-

paedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. x, pp. 8 1 2—20).

* Doctrine in the Church of England (1938), p. 12.

There is only one method for ascertaining

fact and truth, the empirical method. While modernism

and humanism are more or less compromises, dialectical

materialism is its boldest expression. It has its own cos-

mogony, its own interpretation of the origin and nature of

man, its own economic and social scheme, and its own reli-

gion. It proclaims a passionate plea for the spread of light

steady and serene which will help us to get out of the dark-

ness and barbarism of a monkish and deluded past, to shake

oflF the imbecility of blind faith with its fogs and glooms,

and get on to the broad highway of sanity, culture, and

civilization. When we speak of heaven and God we ‘give

to airy nothing a local habitation and a name’. They are

outworn superstitions, subjects of antiquarian interest. Reli-

gions have rendered a useful service in that they have

exhausted all the wrong theories in advance. Everything

can be explained in terms of matter and motion. Marx

accepts the Hegelian view of an immanent reality unfolding

itself by an inner dialectic. But he substitutes matter for

Hegel’s immanent spirit. Matter is invested with the power

of self-movement, auto-dynamism. A self-determining movement whose highest expression is human personality is

regarded as material, and the self of man is denied freedom and responsibility. Criminals and sinners who were

once upon a time consigned to eternal damnation are capable

of being turned into healthy and moral citizens, not by the

grace of God, but by a supply of iodine to the thyroid. Hell

or heaven depends on the twist of heredity or proportion of

phosphorus. Even though man is a product of material

•forces, he is still deified. As the individual man is obviously

too small to be deified, human society gets the honour.

With the Greeks, we reaffirm that the true line of progress

lies in positive action, concrete reasoning, and public spirit.

We oppose nature to custom and repudiate the latter as a

fraud and an imposture. The elaborate framework of cus-

toms which we call morality, which we have built up in our

rise from savagery, and to which we attribute an absolute