FOREWORD

by

Chogyam Trungpa

The eleventh Trungpa Tulku

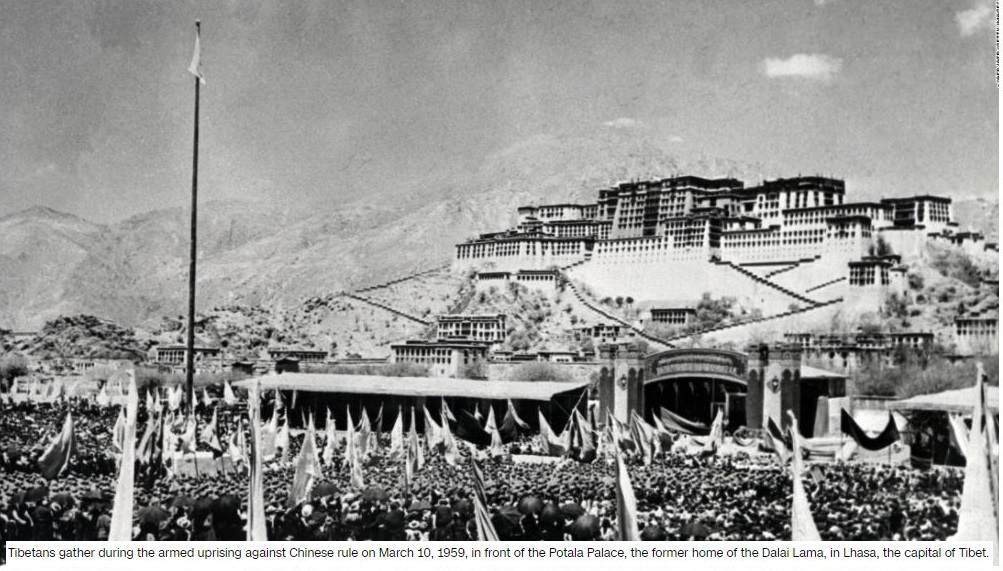

Stories of escape have always enlisted the sympathy of norma human beings; no generous heart but will beat faster as the fugitives from civil or religious persecution approach the critical moment that will, for them, spell captivity or death, or else the freedom they are seeking. The present age has been more than usually prodigal in such happenings, if only for the reason that in this twentieth century of ours, for all the talk about ‘human rights’, the area of oppression, whether as a result of foreign domination or native tyranny, has extended beyond all that has ever been recorded in the past. One of the side effects of modern technology has been to place in the hands of those who control the machinery of government a range of coercive apparatus undreamed of by any ancient despotism. It is not only such obvious means of intimidation as machine guns or concentration camps that count; such a petty product of the printing press as an identity card, by making it easy for the authorities to keep constant watch on everybody’s movements, represents in the long run a still more effective curb on liberty. In Tibet, for instance, the introduction of such a system by the Chinest Communists, following the abortive rising of 1959, and its application to food rationing has been one of the principal means of keeping the whole population in subjection and compelling them to do the work decreed by their foreign overlords. Formerly Tibet was a country where, though simple living was the rule, serious shortage of necessities had been unknown: thus, one of the most contented portions of the world has been reduced to misery, with many of its people, like the author of the present book, choosing exile rather than remain in their own homes under conditions where no man, and especially no young person, is any longer allowed to call his mind his own.

Hostile propaganda, playing on slogan-ridden prejudice, has made much of the fact that a large proportion of the peasantry, in the old Tibet, stood in the relation of feudal allegiance to the great landowning families or also to monasteries endowed with landed estates; it has been less generally known that many other peasants were small holders, owning their own farms, to whom must be added the nomads on the northern prairies, whose lives knew scarcely any restrictions other than those imposed by a hard climate and by the periodic need to seek fresh pasturage for their yaks and sheep. In fact all three systems, feudal tenure, individual peasant proprietorship and nomadism have always existed side by side in the Tibetan lands; of the former all one need say is that it naturally would depend, for its effective working, on the regular presence of the landowner and his family among their own people; in any such case, absenteeism is bound to sap the essential human relationship, bringing other troubles in its train. In central Tibet a tendency on the pan of too many of the secular owners to stop in Lhasa, with occasional outings down to India, had latterly become apparent and this was to be accounted a danger sign; further east, in the country of Kham to which the author belongs, unimpaired patriarchal institutions prevailed as of old and no one wished things otherwise. Of the country as a whole it can be said that, generally speaking, the traditional arrangements worked in such a way that basic material needs were adequately met, life was full of interest at every social level, while the Buddhist ideal absorbed everyone’s intellectual and moral aspirations at all possible degrees, from that of popular piety to spirituality of unfathomable depth and purity. By and large, Tibetan society was a unanimous society in which, however, great freedom of viewpoint prevailed and also a strong feeling for personal freedom which, however, did not conflict with, but was complementary to, a no less innate feeling for order.

At the same time, it must not be supposed that the Tibetans had developed—or had any occasion to develop—an ideology of liberty of the type familiar in the West: a Tibetan experiences freedom (like any other desirable state, moreover) ‘concretely’, that is to say through his being rather than through its conceptual image in his thinking mind. The presence or absence of interference in his life tells him how far he is or is not a free man and he feels little need to call in abstract criteria for the sake of defining his own condition. By nature and habit he is ‘down to earth’, hence also his preference for an almost material phraseology when trying to express the most subtle metaphysical and spiritual truths; that is why our word ‘philosophy’ is but rarely appropriate in a Tibetan context. Whatever a Tibetan undertakes, he will do it wholeheartedly and when the wish to do that thing leaves him he will banish it just as completely from his thoughts. The same holds good for the religious life; by comparison with many of us, an average Tibetan finds contemplative concentration, with its parallel exclusion of irrelevant thinking, easy: the reader need not be surprised, when he comes to the description of the author’s early training under various teachers, at the unswerving single-mindedness shown by one so young. In Tibet this is a normal attitude for one of his kind.

Another characteristic common to Tibetans of all types, not unconnected with the ones already mentioned, is their love of trekking and camping. Every Tibetan seems to have a nomadic streak in him and is never happier than when moving, on ponyback or, if he is a poor man, on foot through an unpeopled countryside in close communion with untamed Nature; rapid travel would be no travel, as far as this quality of experience is concerned. Here again, one sees how a certain kind of life helps to foster the habit of inward recollection as well as that sense of kinship with animals, birds and trees which is so deeply rooted in the Tibetan soul.

Tibetans on the whole are strangers to the kind of sophistry that in one breath will argue in favour of human brotherhood and of the irresponsible exploitation of all Man’s fellow-beings in order to serve that interest reduced to its most shortsightedly material aspect. As Buddhists they know that all are in the same boat, tossed together on the ocean of Birth and Death and subject to a selfsame fatality. Therefore, for those who understand this truth, Compassion is indivisible; failure in one respect will, unfailingly, instil poison into everything else. This is not some abstruse idea reserved for monks or Lamas; people of the humblest degree are aware of it, though the Saints exemplify it more brightly. It is one of the great joys of being in Tibet to witness the results of this human attitude in the lack of fear displayed by bird and beast in all parts of the country. Admittedly most Tibetans, though averse to hunting or fishing, are meat eaters and could hardly be otherwise in a land of such prolonged winters where in any case the range of available foodstuffs is very limited. Nevertheless this fact is accounted a cause for regret; no one tries to prove that it is completely innocent and devoid of spiritually negative results. It is a common practice for people to abstain from the fruit of slaughter on certain days, as a kind of token of intent; while anyone who succeeds in keeping off meat altogether, as in the case of certain Lamas and ascetics, will invariably earn praise for doing so.

It is hard to believe that if such an attitude were more general the prospects of peace on Earth would not be that much brighter. If one wishes to pull up the taproot of war one has to seek it at a level for deeper than that of social or political events. Every Tibetan faithful to his tradition know’s this plainly; it is only when he adopts the ways of our civilisation that he will begin to forget this truth, together with many other things.

* * *

It may perhaps now help the reader to be told something about the historical background of the present story, with particular emphasis on such events as affected conditions in eastern Tibet during the period just prior to the time when the author’s personal narrative starts.

After the Chinese revolution of 1912, when the Manchu dynasty fell, the suzerainty the Emperor had exercised in this country (since 1720) was repudiated by the Tibetans; Chinese influence in Tibet had in any case been dwindling all through the nineteenth century. Not long before the fall of the Manchus, their last viceroy in the westerly Chinese province of Szechuan, Chao Erfeng, a hard and ambitious man, made an attempt (the first of its kind) to bring Tibet under direct Chinese administration; his troops occupied Lhasa in 1910. When the empire collapsed, however, giving way to a republic, the Tibetans rose and drove out the Chinese garrisons from the two central provinces of U and Tsang; Tibetan national independence in its latest phase dates from that time. Moreover, a further extension of the territory governed from Lhasa took place in 1918, when Tibetan forces succeeded in occupying the western part of Kham which thenceforth remained as a province of Tibet with its administrative centre at Chamdo, a place often referred to in the pages to follow.

The new Sino-Tibetan boundary consequently ran through the middle of the Khamba country, with people of Tibetan race, that is to say, dwelling on both sides of it; but paradoxically it was those districts that remained nominally under China that enjoyed the most untrammelled independence in practice. Occasional interference from neighbouring Chinese ‘war-lords’ apart, the local principalities, akin to small Alpine Cantons, which provided the typical form of organisation for a valley, or complex of valleys, in this region were left so free to manage their own affairs that people there must have been practically unconscious of, and equally indifferent to, the fact that, in the atlases of the world, their lands were coloured yellow as forming part of greater China. Under these conditions, which went back a long time, the Khambas had developed a peculiar sense of local independence which needs to be understood if one is to grasp the significance of many of the events mentioned in this book.

By comparison with the districts still attached to China, the part of Kham governed by Lhasa-appointed officials felt, if anything, less free; which does not mean, however, that the Khambas were lacking in loyalty to the Dalai Lama, as spiritual sovereign of all the Tibetan peoples: they were second to none in this respect. Only they did not see why an unbounded devotion to his sacred person need implv any willingness to surrender jealously treasured liberties at the bidding of others acting in his name. In their own country the Khambas much preferred the authority of their own chieftains (‘kings’ as the author describes them), personally known to everyone; laws or levies imposed from a distant centre was not a thing of which they could recognize the necessity, for their own valleys had always run their own affairs quite successfully on the basis of a self-contained economy and from their point of view nothing was to be gained, and much lost, by exchanging the old, homely arrangements for control by the nominees of a capital that lay in another province far to the west. Besides, some of the governors sent to Chamdo made matters worse by extorting from the local inhabitants more perquisites than what long established custom would sanction. When the Chinese invaded Tibet in October 1950 they were at first able to exploit these discontents in their own favour by saying they would put an end to the exactions of the Tibetan officials. It was not till afterwards that the clansmen of those parts realized, too late, that the change from capricious harassment to a meticulously calculated squeezing had not worked out to their advantage. It is hardly surprising that when eventually popular exasperation at Communist interference broke out in armed revolt it was the Khambas who bore the brunt of the patriotic movement and provided its most daring leaders.

It is hoped that enough has now been said by way of setting the stage for the Lama Trungpa’s reminiscences: these are given with typically Tibetan matter-of-factness; he neither tries to feed the reader with opinions nor does he, for the sake of logical coherence, introduce information gathered after the event; the inevitable gaps in one man’s experience are left, just as they were, unfilled. All the author does is to relate whatever he himself saw, heard and said; as each day brought its fresh needs and opportunities, he describes how he tried to act, adding nothing and omitting nothing—the Lama obviously has a most retentive memory for detail. Surely this way of presenting facts makes the documentary value of such a chronicle all the greater, illustrating, as it does, all the hesitations and uncertainties of a situation no one was prepared for, the doubts, the changes of plan, the conflicts of advice, out of which gradually grows the firm resolve, carrying out of which forms the second and most dramatic part of the book.

The first appearance of the Communists on what previously seemed like an idyllic scene is typical, it occurs almost casually: when they turn up one day people ask themselves what this means, but when nothing very unpleasant happens—none of the expected looting by the soldiers, for instance—everyone soon settles down again to his usual preoccupations. The soldiers pass on; the incident is half forgotten. It is only some pages later that one discovers them again, first just across the Tibetan frontier at Chamdo, and long afterwards in occupation of Lhasa, but how they got there one is not told. After a time one guesses that Tibet has capitulated, but is given few details simply because those actually involved in these events were often too cut off in their own locality to obtain a bird’s eye view; we in England, watching the international scene from afar were, in some respects, better able to build up a general picture.

In fact, as the book shows, it was by no means easy for people in those remote districts immediately to form clear ideas about the nature of the new order in China. Moreover this also partly explains why the Tibetan Government itself, while the Communist threat was developing, was rather hesitating in its reactions; a temporizing policy, so often resorted to by small nations facing pressure from a great Power, may well have seemed preferable to crying Tibet’s wrongs from the housetops regardless of consequences. The Lhasa government has been criticized, with a certain justice, for lack of initiative in face of a danger calling for swift decisions; but it is only fair to make considerable allowance for circumstances, material and psychological, that were inherent in the situation from the very start of the crisis.

The above remarks have somewhat anticipated on the sequence of events. The point I am trying to make is that it necessarily took some time before the author, young as he was, or his senior advisers were able to gather any precise impressions of what was to be expected under Communist rule. As the story unfolds we see an initial bewilderment gradually giving way to acute discomfort which in its turn becomes a sense of impending disaster. We hear that fighting has broken out in a certain valley, yet the adjoining valley may still be seemingly in enjoyment of its habitual calm, with everyone there intent on peaceful tasks—adding a wing to the local temple perhaps or preparing for the reception of a revered Spiritual Master. Eventually, however, the more wide-awake characters in the book begin to realize that this is no passing crisis: Tibet and its cherished way of life are facing a catastrophe without parallel in the past, one that no policy of ‘wait and see’ will enable one to live down. It is a time for far-reaching decisions if certain values, as well as one’s own life, are to be preserved: here again, one is allowed to see into the conflict of outlook between those who cling to the belief that this trouble, like others before it, will blow over if only people will have the patience to sit tight and those others who think that their imperative duty is to carry whatever they can of Tibet’s spiritual heritage to some place where the flickering spark can be rekindled in freedom; flight to India, the Buddha’s native land, seems the only remedy left to them. These two much canvassed points of view become focussed, in this story, in the persons of the author himself and his elderly bursar, a well meaning man not wanting in devotion, but typical of the mentality that is for ever fighting shy of any solution that looks like becoming irrevocable. There is much pathos to be gathered from these repeated encounters between youthful virility ready to take the plunge and inbred caution for which ‘stick to familiar ways and wait’ is the universal maxim to fit every unprecedented emergency.

About the actual escape there is no call to speak here, except by remarking that at least one reader, while following this part of the story, has been repeatedly reminded of those young British officers of the late nineteenth century who found themselves launched by fate into positions of unusual responsibility at remote outposts of the Empire: one meets here the same readiness to take crucial decisions time and again, the same light-hearted spirit maintained over long periods of suspense and danger and, in more critical moments, a similar capacity for instilling courage into the timid and endurance into the weakly by the well turned appeal, the timely sally—all these qualities were displayed by the chief actor in this drama in a completely unselfconscious manner.

But after making this comparison, one still has to admit a certain difference, itself due to a very great difference in the respective backgrounds. This can be summed up in the fact that in the one case, aptitude for leadership rests on an acceptance of what are predominantly ‘Stoic’ loyalties and values—Marcus Aurelius would have shared them gladly—whereas in the other, it is from the heart of Contemplation that this strength is drawn forth; the centre of allegiance lies there, thus endowing whatever action has to be taken under pressure of necessity with an unmistakable flavour of‘inwardness’. It is the Lama who, speaking through the man, delivers his message and that is why, over and above its human and historical interest, this book has also to be treated as a Buddhist document in which much may be discovered by those who have the instinct to read between the lines. It is noticeable that whenever a pause in the action occurs there is an almost automatic withdrawal back into contemplation; the mind wastes no time in dwelling on its anxieties but finds within its own solitude, as well as in the stillness of Nature, the means of refreshment and renewal.

That a mind so attuned should harbour no enmity in return for injuries received seems only logical; in this respect the present history may well be left to speak for itself. Buddhism has always had much to say, not only about ‘Compassion’ as such, but also about what might be called its ‘intellectual premisses’, failing which that virtue can so easily give way to a passional benevolence that may even end up in hatred and violence; this has been the persistent weakness of worldly idealists and of the movements they promoted. For Compassion (or Christian Charity for that matter) to be truly itself it requires its intellectual complement which is dispassion or detachment: a hard saying for the sentimentalists. Though feeling obiously has as a place there too, it can never afford to bypass intelligence—as if anything could do that with impunity! This is a point which Buddhism brings out with implacable insistence: from its point of view Compassion must be looked upon as a dimension of Knowledge; the two are inseparable, as husband and wife. All this belongs to the basic tenets of the Mahayana or ‘Great Way’, of which the Tibetan tradition itself is an offshoot; Tibetan art is filled with symbolical delineations of this partnership. It is important for the reader to be made aware of the fact that these ideas pervade the entire background of the author’s thinking, otherwise he will miss many of the finer touches.

It would be ungrateful to terminate this introduction to a remarkable book without some reference to the lady who helped the Lama Trungpa to put down his memories on paper, Mrs Cramer Roberts; in fact, but for her encouragement in the first place, the work might never have been begun. In interpreting what the Lama told her of his experiences she wisely did not try and tamper with a characteristically Tibetan mode of expression beyond the minimum required by correct English; in all other respects the flavour of the author’s thought has been preserved in a manner that will much increase the reader’s ability to place himself, imaginatively, in the minds and feelings of those who figure in the narrative; a more inflected style, normal with us, could so easily have covered up certain essential things. For the fine sense of literary discernment she has shown we all have to thank Mrs Cramer Roberts, as also for the unstinting devotion she brought to her self-appointed task.

MARCO PALLIS

Marco Pallis (1895-1989) was a Renaissance man: a gifted musician, composer, mountaineer, translator, and a widely respected author on Tibetan Buddhism and the Perennial Philosophy. Pallis was a regular contributor to the British journal Studies in Comparative Religion and was a distinguished member of the “Traditionalist” or “Perennialist” school of comparative religious thought. His eloquent writings focus on Buddhist doctrine and method, but are noteworthy for their universalist outlook.

Marco Alexander Pallis was born in Liverpool, England, in 1895, the youngest son of wealthy and cosmopolitan Greek parents. He was his mother’s favorite child—different, more sensitive than his other siblings—and from an early age was interested in religion. While studying at the exclusive all-boys school Harrow, he asked the chaplain to give him special Bible lessons. As a young man studying at Liverpool University he became deeply attracted to Roman Catholicism, though this met with strong disapproval from his Greek Orthodox parents. While Pallis’ life seemingly began far removed from the land of Chenrezig, Vajrayana, and Tantra, there was one exception: his parents, who had lived in India for several years, decorated the house in which the young Marco was raised with works of Indian and Oriental craftsmanship. For an artistic and receptive youth, it was a subtle first beckoning from the East.

Still young during the Great War, Pallis, after having briefly aided the Salvation Army in Serbo-Croatia, enlisted in the British Army. His first commission was in 1916 as an army interpreter in Macedonia. Malaria and a severe inflammation of his right eye cut short his Macedonian service. After a forced, lengthy convalescence in Malta, Pallis applied and was accepted to the Grenadier Guards. He first received basic training, then advanced training as a machine-gunner. In 1918, as a second lieutenant, he was sent to fight in the trenches of the Western Front. During the battle of Cambrai, in a charge that killed his captain and first lieutenant, Pallis was shot through the knee; for Pallis the war was over.

Following the war, in addition to family duties, Pallis occupied himself with what were then his two loves: mountaineering and music. He climbed and explored whenever and wherever he could, and this despite the fact that doctors had told him that he might never walk on his injured knee again. He went on expeditions to the Arctic, Switzerland, and the Dolomites, while Snowdonia, the Peak District, and the Scottish Highlands provided him with opportunities closer to home. At the same time Pallis studied music under Arnold Dolmetsch, the distinguished reviver of early English music, composer, and performer.[1] Under Dolmetsch’s influence, Pallis soon discovered a love of early music—in particular chamber music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—and for the viola da gamba. Even while climbing in the region of the Satlej-Ganges watershed, he and his musically-minded friends did not fail to bring their instruments. Dolmetsch also influenced Pallis intellectually, through pointing the way to the writings of the traditionalist metaphysician and critic of the modern world René Guénon, and the great Indologist and historian of sacred art Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. These authors helped Pallis to see the indispensable role tradition plays in perpetuating the transcendent and foundational ideals of a civilization. This understanding of tradition per se, was to inform Pallis’ later writings on Tibet and its traditions

His love of mountains was destined to help guide Pallis to his third—ultimately all-encompassing—love: Tibet and its civilization. In 1923, for purposes of climbing, Pallis visited Tibet for the first time. He returned to the Himalayas for a more prolonged climbing expedition in 1933 and again in 1936. His best-selling book Peaks and Lamas describes these latter treks and the transformation that he underwent. “In the Tibet we visited . . . the whole landscape was as if suffused by the message of the Buddha’s Dharma; it came to one with the air one breathed, birds seemed to sing of it, mountain streams hummed its refrain as they bubbled across the stones, a dharmic perfume seemed to rise from every flower. . . . The India of King Ashoka’s time must have been something like this; to find it in mid-twentieth century anywhere was something of a wonder.” From being an outsider, sympathetic but merely looking on, he penetrated ever deeper into the heart of Tibetan life. “I never felt that I was among strangers; rather was it a return to a long-lost home.” He discarded his western clothes in favor of Tibetan dress, and furthered his study of the Tibetan language, culture, and religion. Often staying in monasteries, he received his religious education directly from lamas from within the living tradition.[2] The Second World War[3] prevented further travels until 1947, when, in what proved to be a last-minute opportunity, he and his friend Richard Nicholson were able to visit Tibet a final time before the coming Chinese invasion. Already a practicing Buddhist since 1936, while in Shigatse, Tibet, Pallis was initiated into one of the orders; he was fifty-two years old. By the time he left Tibet, one could say that Marco Pallis—now Thubden Tendzin—had completed the inward journey to his spiritual home. He continued to be a faithful practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism—and a tireless advocate for Tibet—until his death some forty-three years later.

After his 1947 journey to Tibet, Pallis lived in Kalimpong for several years, returning to England in 1952. Kalimpong was then a center of literary and cultural activity, as well as a refuge for those who were being forced to leave Tibet, including the tutor of the Dalai Lama, Heinrich Harrer, who, immediately upon his arrival in Kalimpong, began to write his Seven Years in Tibet. Pallis formed many lasting relationships during this time, including an acquaintance with the then queen of Bhutan and her family, with whom he later visited in England, and with Heinrich Harrer, with whom Pallis later collaborated in exposing the fraudulent writer Lobsang Rampa. While in Kalimpong, Pallis also met with the Dalai Lama’s Great Royal Mother, and he developed a close relationship with the elderly abbot of the nearby Tharpa Choling monastery.

A brief but informative glimpse into Pallis’ domestic life in Kalimpong is provided to us by Urgyen Sangharakshita (born Dennis Lingwood): “The bungalow was situated at the top of a flight of irregular stone steps, and what with trees looming up behind and shrubs pressing in on either side it was a sufficiently quiet and secluded place. Here Thubden La, as he liked to be called, lived with his friend Richard Nicholson, otherwise known as Thubden Shedub, the companion of the travels recorded in Peaks and Lamas. As lunch was not quite ready, he showed me around the place. Tibetan painted scrolls hung on the walls, and the polished wooden floors were covered with Tibetan rugs. There were silver butter-lamps on the altar, and massive copper teapots on the sideboard, all gleaming in the shuttered semi-darkness. In one room I could just make out the unfamiliar shape of a harpsichord.”

The overthrow of independent Tibet by the Communist Chinese marked one of the saddest events in Pallis’ life. In response, Pallis did what he could, mostly through his writings, which helped to raise public awareness of the wonder that was Tibet. It must have also given Pallis much pleasure to be able to help members of the Tibetan diaspora in England. On multiple occasions, Pallis opened up his London flat to house visiting Tibetans. He offered his help through other ways as well, such as with the young Chögyam Trungpa. Pallis traveled with and encouraged Trungpa, who had just arrived in England, and had not yet garnered the world renown he was soon to achieve. Some years later, Pallis was asked to write the foreword to Trungpa’s first, seminal book, Born in Tibet. In his acknowledgement, Trungpa offers Pallis his “grateful thanks” for the “great help” that Pallis gave in bringing the book to completion. He goes on to say that “Mr. Pallis when consenting to write the foreword, devoted many weeks to the work of finally putting the book in order.”

Born in Tibet – The Book