Bible Review 9:6, December 1993

How the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament Differ

An interview with David Noel Freedman 1922-2008)

Part I

HS: As you probably know, among your colleagues and friends you are thought of as both Jewish and Christian.

DNF: Right. I’ve never made a special issue about that. I have never been observant but, if I understand correctly, the basic definition of a Jew is that your mother is Jewish. That’s certainly true in my case. I have never renounced Judaism, but if it’s automatic that when you profess Christianity you’re no longer a Jew, then I’m no longer Jewish. But my own attitude is that you can be Jewish and Christian at the same time.

HS: You have spent your life in Hebrew Bible scholarship.

DNF: Right.

HS: That’s essentially a Jewish document.

DNF: It’s also a Christian document.

HS: Correct.

DNF: Which is really why I picked that, because it allows me to satisfy my own concern about my identity. If I stick to the Hebrew Bible, I can be both.

HS: You obviously study these texts from a dual perspective, from a Jewish perspective and from a Christian perspective. Are there differences in these perspectives?

DNF: Oh, a dramatic difference. It has taken me a long time to realize that there is such a difference. But there is also a basic scholarly approach to the Hebrew Bible that is neither Christian nor Jewish, where there’s a kind of common denominator, where people with different persuasions, different commitments can meet.

HS: Can you give us an example of the different perspectives?

DNF: Yes. The use made of the Hebrew Bible in the New Testament pretty much determines the Christian approach to the Old Testament. In the New Testament, the Hebrew Bible is regarded as a book of prophecy and prediction—the view that many Old Testament predictions are fulfilled and realized in the New Testament.

The writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls also used the Hebrew Bible as a collection of predictions and prophecies that find fulfillment in their own experience, according to their understanding. For example, take the Dead Sea Scroll known as the Commentary on Habakkuk, or Habakkuk pesher. The Book of Habakkuk itself is about the Chaldeans (the neo-Babylonians) who conquered the world. The prophet has a lot of things to say about them. Well, what does that mean to people 400 or 500 years later, when the Chaldeans have vanished from history? The Dead Sea Scroll people use a neat little device in the Commentary on Habakkuk and elsewhere: They assume the prophets themselves weren’t entirely aware of what their words meant. But thanks to the inspired interpreter, the Teacher of Righteousness, their leader, they could now understand the real meaning of the prophet’s words, which are, after all, the words of God. For the Dead Sea Scroll people, Habakkuk is really about the Kittim, not the Chaldeans. It’s like the joke [William F.] Albright used to tell about what Moses and Middlebury had in common. Well, you take off “oses” and add “iddlebury” and they’re the same. [Laughter] That’s exactly what these [Dead Sea Scroll] people were doing, They’re simply replacing the Chaldeans with the Kittim.

HS: Who were the Kittim?

DNF: A code name either for the Seleucid Greeks in Syria or the Ptolemaic Greeks in Egypt or possibly the Romans. They are the contemporary conquerors and invaders.

The device is easy to see: Since the Dead Sea Scroll people didn’t have a prophet of their own, the next best thing was to have an inspired interpreter. They used prophecy that everybody accepted as authoritative and adapted it. No problem with this, except that according to these people theirs is the only, the real, interpretation. This isn’t just homiletics. This describes a convergence of all the events recounted in the prophets of the past about this present eschatological moment, when everything’s going to change.

As an academic exercise, that’s very interesting and challenging. No problem. A few years pass, however, and that interpretation becomes obsolete, so you make another adjustment, with a different interpretation. And ultimately you give up the whole thing because the prophecy is equally applicable to this period, to that period, to another period, or inapplicable to any of them, because what the prophet says just doesn’t happen. Then you banish the prophecy to a distant future.

But when you say, “This is the only way, this is the real meaning and any other interpretation is invalid,” then you’re creating a problem.

When this happens, I think you have to go with the text, not with the commentary. You have to understand the text in its own historical setting, just as any scholar would do with any piece of literature.

HS: Is this the same thing that was going on in Christian texts?

DNF: Indeed, it is. One of the most famous, or infamous, passages [in the King James Version] is the passage in Isaiah 7:14: “A virgin shall conceive and bear a child.” The Gospel of Matthew [1:18–23] makes this explicit, that the prophet is talking about the birth of Jesus Christ. If you read Isaiah 7:14 in Hebrew, however, there’s a problem about the meaning of the Hebrew word almah. Does it mean young girl or virgin? In the Greek Septuagint it is translated parthenos, which is virgin. Matthew was apparently relying on the Septuagint, which may have mistranslated almah. That’s one problem. In addition, the context of Isaiah 7:14 makes it clear that the prophet is talking about his own day, something that’s going to happen within a very few years and that, in fact, has already happened, so the prophecy was fulfilled. What does that have to do with Jesus Christ 700 years later? Well, that’s the Christian perspective, the New Testament perspective. These people are convinced that Jesus is the messiah and therefore they comb the Old Testament for prophecies and anything that pertains or seems to pertain to this belief or illustrates it. And this is all brought into focus by the events surrounding Jesus.

The principle [of interpretation of scripture] is the same as in the Dead Sea Scroll texts. Now obviously Jews don’t have the same perspective.

HS: What’s the Jewish perspective?

DNF: Well, that varies. After all, the methods we’ve just described were invented and practiced by Jews. The idea of using the Hebrew Bible in this way is a Jewish way; it’s not non-Jewish.

HS: But Jews don’t seem to use this method of interpretation.

DNF: Not anymore. They got burned by all this in two ways: One was the final collapse of all of this eschatological, apocalyptic expectation. When the Romans suppressed the Second Jewish Revolt, the Bar-Kokhba Revolt [132–135 A.D.], the Jews finally abandoned this expectation of the immediate apocalyptic moment. Some thought that Bar-Kokhba was the messiah. He proved not to be. So the Jews adapted to the situation in other ways. The second factor was the incredible rise of Christianity, which in a way took their [the Jewish] scriptures and turned the Bible against them; I think this cured the Jews of this kind of speculation—until the Middle Ages when there were other messianic movements and some parts of this got revived again.

HS: What is the alternative Jewish approach to the Hebrew Bible?

DNF: The major concern of traditional Judaism has been the Torah and halakhah [Jewish religious law]. In other words, how to interpret and understand the teachings and the rules of the Bible so that people can practice them. This is an entirely different orientation.

As you know, the Bible itself is not always clear or entirely consistent. The Bible can seem to say one thing at one place and something different at another. So how do you actually practice what it teaches? Answering that is almost the whole history of rabbinic interpretation.

There is much more flexibility in Jewish interpretations of prophecy and predictions [than in the legal sections of the Hebrew Bible] because these things aren’t decided in a legal way. You’re not determining practice.

Of course there’s a great variety between Orthodox Judaism and Reform Judaism.

But my concern is entirely with scholarship. I’m concerned with the underlying requirements of scholarship. You have to be faithful and true to questions of language, grammar, vocabulary and you have to deal with historical and other contexts and simply try to recover the meaning of the original. This is a common endeavor everybody can get into, but they have to leave some of these prior convictions and commitments outside.

HS: I was going to ask you about these prior convictions. Does your interpretation of the Christian approach to the Old Testament imply a literal belief in the Gospels, for example, that interpret the Hebrew Bible in this predictive stance?

DNF: There are at least two separate questions here. One is the way in which the Old Testament is used. And certainly we can describe that.

HS: You did a moment ago.

DNF: This has little or nothing to do with real history or the intention of the prophet. On the other hand, the Gospels constitute a narrative and they are subject, just like the narratives of the Old Testament, to questions of historicity and evidence and reasonability. It’s really the same.

I don’t believe that the Old Testament was ever meant to support the narrative in the Gospels. The conviction about Jesus’ messiahship and resurrection had very little to do with the Old Testament. But once these things became the basis of Christian profession, then the Old Testament was used to demonstrate or to enhance belief. When it comes to the historical question about the Gospels, I adopt a mediating position—that is, these are reliable records, close to the sources, but they are not in accordance with modern historiographic requirements or professional standards. In all ancient writings, you find elements of naivete or credulity. Even Josephus and classical historians like Herodotus and Eusebius include a lot of material that we can’t accept as rigorous historical inquiry.

HS: I take it the biblical text can still be used for inspirational and theological purposes.

DNF: And also for historical purposes. But we have to accept somewhat looser standards. In the legal profession, to convict the defendant of a crime, you need proof beyond a reasonable doubt. In civil cases, a preponderance of the evidence is sufficient. When dealing with the Bible or any ancient source, we have to loosen up a little; otherwise, we can’t really say anything.

HS: Your personal background is very secular. How did you become interested in the Bible, in biblical scholarship?

DNF: That relates to my conversion and that arose out of personal experience. My concern at the seminary was to find a way to adjust to this new life. I turned out to be a little more academic than I thought I was. The Bible has a fascination all its own, partly because of its antiquity, but mainly because of its literary character. Catholics, Protestants and Jews, as you know, have different Bibles. The one thing they have in common is the Hebrew Bible. I call it the Common Bible. This Bible that’s common to everybody is the foundation. I had a naive notion that the Hebrew Bible could provide a basis for not only dialogue, but also for some kind of reconciliation among religious communities.

The Hebrew Bible is the one artifact from antiquity that not only maintained its integrity but continues to have a vital, powerful effect thousands of years later.

I believe that, in its present form, the Hebrew Bible is a product of a very carefully worked-out plan to achieve symmetry, totality, even perfection. There’s a deliberate effort made to pool together all the heterogeneous elements in the Jewish tradition and make a single whole. This book was intended to reflect what they believed about the perfection of God, more especially about the importance of his word. It was to reflect in written form the activity of God in the world and the link between members committed to this word. Just as God created the universe and rules the universe and directs history through the word spoken, here in the Bible is the word written. It’s the equivalent of the word spoken. This makes the Bible something even more special, not just another relic from antiquity. It has a unique quality. My brother, who is a professed atheist, says the Bible is the richest source that he knows for human experience.

HS: This has been an abiding concern of yours, to explore the overarching connections within the entire text of the Hebrew Bible. Your most recent book is called The Unity of the Hebrew Bible.

DNF: That’s correct. Actually I have published another book since then with Sara Mandell, The Relationship between Herodotus’ History and Primary History. It’s a comparison between the Primary History in the Bible (Genesis through Kings) and Herodotus, who is often called “the father of history.” We try to show that if there’s any priority here, it belongs to the Bible. Moreover, the Primary History in the Bible achieves greater unity, greater focus, is more of a history than Herodotus.

But, to return to the unity of the Hebrew Bible, I’ll give you my view on that. It might help first to identify a real chasm between Jewish and Christian belief here.

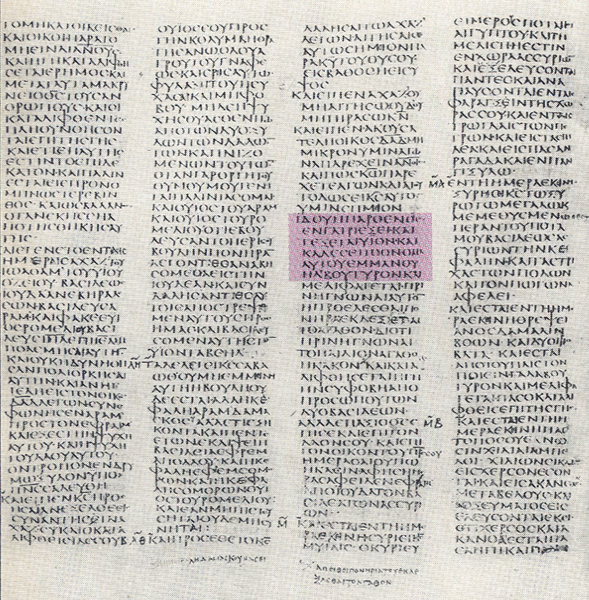

As is well known, the arrangement of the books is very different in Christian Bibles and Hebrew Bibles. The Christian order is based on the Old Greek Bible, the Septuagint. Originally, this was a Jewish translation, but all the copies of it that have survived—from the fourth century on—were preserved by Christians. The last section of Christian Bibles, following the order in the Septuagint, contains the literary prophets, ending with the prophet Malachi.

The order in the Jewish tradition is different from the order in the Christian tradition. Both begin with what I call the Primary History—the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses) plus Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. The Christian tradition varies here only by the insertion of Ruth between Judges and Samuel.

In the Jewish tradition, the Primary History is followed by the literary prophets—the three major literary prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel) and the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets.

Not so in the Christian tradition. In the Christian tradition, these four books of the literary prophets plus the Book of Daniel are placed at the end. Malachi, the last prophet in the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets, leads directly into the Gospels, which are supposed to be the fulfillment of these prophecies.

For Christians, the Old Testament is a book of prophecy and prediction of the coming of the Messiah that is fulfilled in the New Testament. Basically, with the coming of Jesus Christ the predictive factors in the Old Testament are fulfilled or, if not fulfilled, are largely fulfilled with others yet to come.

Now what is the Jewish view of the Hebrew Bible?

From the Jewish perspective, the Bible is divided into two halves. The first half is the story of the fall of Israel (Israel and Judah, after the kingdom divides), how they lost the land, lost their city, lost their Temple, everything. It’s the fall of Israel.

HS: Ending with the Babylonian destruction in 586 B.C.E.?

DNF: Correct.

HS: And beginning with creation?

DNF: Right. That’s the Primary History—from creation to the destruction of the Temple—the five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy—of course they have different names in Hebrew) plus Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. That’s the first half. The first half is tragic. If that’s all they were interested in, that would be the end. But what the Hebrew Bible is really all about—in Jewish tradition—is how they came back. That’s the last half, the story of the return.

Both parts are equally important. This is really a quasi-legal brief on behalf of Israel and its claim to the land. The contention is that even though the original grant of land to them was conditional—provisional—and they failed to maintain the conditions—they didn’t fulfill the requirements of the covenant and they lost the land—nevertheless, over-riding this historical truth is the original commitment made by God to Abraham in Genesis 15 (and repeated elsewhere to Abraham and his descendants). There it’s spelled out. God committed himself by oath to give the land to Abraham and his descendants. According to their understanding, even if they deserved to lose it and lost it, they still have this claim because the original commitment was unconditional, irrevocable—“To your offspring, I give this land” [Genesis 15:18]—and there’s no way it can be reversed.

HS: And this is the story of the second half of the Hebrew Bible?

DNF: Yes, especially Chronicles. In Jewish Bibles today the last book is Chronicles, after Ezra-Nehemiah. This actually makes no sense, because it is in reverse chronological order. Chronicles begins with creation and takes the story up to a certain point and then Ezra-Nehemiah takes it from there. Nevertheless Chronicles is the last book.

But in the best and oldest copies of the Hebrew Bible—the Aleppo Codex around 900 C.E. and the Leningrad Codex shortly after 1000—the arrangement is different. Chronicles appears immediately after the literary prophets, and Ezra-Nehemiah is the last book of the whole Hebrew Bible. This section from Chronicles to Ezra-Nehemiah is known in Jewish tradition as the Writings [Ketuvim]. It is the third major section of the Hebrew Bible. The first is the Torah, the Pentateuch. The second is the Prophets (Nevi’im), which in Jewish tradition includes the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (the four books of literary prophets). In the Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad Codex, the Writings begin with Chronicles and end with Ezra-Nehemiah. These two historical narratives (Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah) form an envelope around the Writings, what we call an inclusio.

Chronicles begins with the word “Adam.” This is clearly an echo of Genesis, obviously recapitulating the whole story. But this time it is the story, not only of how they lost the land, but also how they got it back.

HS: How is that conveyed?

DNF: At the end of the story—Ezra-Nehemiah—they’re back in the land, the Temple has been rebuilt, they’ve reoccupied Jerusalem and Nehemiah has put in the last piece of the puzzle—the walls. Jerusalem is once again a walled city. This has great significance; her integrity has been restored.

The only thing missing is that they’re not entirely free; they don’t have their own king. But that’s for the future. Because this is history and not fiction, it can’t be a complete circle, because that isn’t the way things really happened. That’s going to happen later, however. That’s the reason the Book of Daniel was added, to bring the story up to date 250 years later. The Book of Daniel is the odd man out.

But the point is that the Hebrew Bible in its totality is a quasi-legal brief for Israel’s right to be on that land. The whole story is how it was promised by divine grant, how they occupied it, how they lost it and how they got it back. And finally, there is a messianic future. That remains yet to be fulfilled.

The literary prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets) form a kind of connecting link between the Primary History, which I’ve already described, and the Writings. The literary prophets are called the Latter Prophets in Jewish tradition, as opposed to the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings), which form part of the Primary History. The Primary History ends when they lose the land and they are carried into captivity. The Latter Prophets overlap with this story. They start before the end of that story but go beyond it, with the return and the imminent rededication of the Temple at the end of First Zechariah (chapters 1–8).c In other words, that gives us the transition. And then the Writings are a heterogeneous collection, enclosed in an envelope, with Chronicles at the beginning and Ezra-Nehemiah at the very end, tying the whole thing together within this context of the promise of the land, the occupation of the land and then the loss and the resettlement.

HS: How do you account for the fact that in Jewish tradition you have the Former Prophets and the Latter Prophets? In your division, you put the Former Prophets with your Primary History.

DNF: There is a symmetry here, a bilateral symmetry that we see again and again. There are four Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings—1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings are each regarded as single books in Jewish tradition.) Ruth is not in the former prophets but in the Writings, where it is grouped with the four other Megillot [Scrolls: Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Esther]. And there are four Latter Prophets (the literary prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Book of the Twelve). The Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets is always one book. That’s an artificial way to establish symmetry.

I divide it somewhat differently. I believe that the Primary History was one unit and that the Torah was then separated from the Primary History.

HS: The Torah being the five books of Moses?

DNF: Right. Normal scholarship holds that the Torah came first and the Former Prophets were added to make the Primary History. I think the Torah was extracted from the whole Primary History for a reason—to create a legal constitution, a document that would be the law of the land. The Primary History is a story. The Torah is intended to be a law. In fact, neither quite fills the bill because the Primary History has a great deal of legislation in it. The Torah is laws, but it has the Book of Genesis, which isn’t law. Most scholars agree that Deuteronomy goes with the Former Prophets to form the Deuteronomic History. Deuteronomy is really the introduction to the Deuteronomic History.

The only analysis that makes literary sense is that the entire Primary History is a unit. Any other division produces anomalies. For example, if you divide the first four books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, the so-called Tetrateuch—from Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic History, you’re in trouble because you end up at the end of Numbers where you’re not supposed to be, in Transjordan. The Israelites haven’t made it to the Promised Land, the land promised in Genesis. You’re stopping in the middle because the fulfillment of Genesis, with all its promises, can only come in Joshua. It doesn’t come in Numbers or Deuteronomy.

HS: Is that why the Samaritan canon includes Joshua and that’s all?

DNF: Well, that’s yet another story. In classical critical analysis we talk about the Hexateuch—the Pentateuch plus Joshua.

HS: In Joshua they take possession of the land?

DNF Yes. The west bank of the Jordan, not the east bank, because the west bank is what was promised to Abraham. The conquest of the east bank, which is in Numbers, is more or less an accident. So, that can’t be the literary connection.

HS: According to common scholarly belief, the Pentateuch was canonized by Ezra and Nehemiah, or in that period when they from the Exile.

DNF: Right.

HS: But you are saying that they canonized more than that, that they canonized the entire Primary History?

DNF: More than that, the whole Bible.

HS: So it all must have been written by then.

DNF: Yes, I think it was, all except Daniel. The way I see it is this: Ezra is the one who establishes the authority of the law in the restored community, We are told this quite dramatically; in our last image of Ezra, in Nehemiah 8:13, he is reading from the Torah to the people. I believe Ezra is responsible for the formation of the Torah out of the Primary History, which already existed. That’s how the division after Deuteronomy occurred. Practically all the laws are contained in the first five books, and the law is what Ezra is trying to get the people to commit themselves to do, to live by the words of this document.

Then I believe Ezra wrote his own memoirs (the Book of Ezra) and died. The overall work, however, was done by Nehemiah; he has the last word in the Hebrew Bible. And what is it? “Remember me, oh my God, for good.” Nehemiah is like King James; he’s the executive (i.e., the Governor) who sponsored this. He put up the money, and he’s unhappy because he didn’t get enough credit, His book is about putting everything together. The words with which the Hebrew Bible (that is, Nehemiah) ends are “Zochrah li Elohay l-tovah” “Remember me, oh my God, for good.” The two key words are Elohay, simply a form of Elohim—God, and tovah, the feminine form of tov—good. The dominant words in the first chapter of Genesis are Elohim and tov, “God” and “good.” After every day’s work, God says, “It’s good.” I think in Nehemiah, which according to the most reliable witnesses (the Aleppo and Leningrad codices) ends the Hebrew Bible, we have an echo of the very beginning of the Hebrew Bible. The word Elohim is repeated, while the pair tov and tovah form a merismus or totality. It’s as if to say at the very end, very deliberately, “Now we are done.”

HS: When Ezra-Nehemiah put the whole thing to-gether (except for Daniel), was the Primary History already in existence?

DNF: Yes.

HS: When was that done?

DNF: Well, my answer is based on the axiom, the simpler the better. When dose the Primary History end? It ends with the Exile, following the Babylonian destruction in 586 B.C.E. There’s no hint in the entire Primary History of the actual return from Exile.

HS: You think the Primary History was put together somewhere in Babylonia during the Exile?

DNF: Definitely. What else did they have to do? And the two people who could produce an authoritative work like that—the king and the high priest—were both in exile in Babylon. They could give it the imprimatur, the stamp of authority, the prestige that are required.

I think that’s what happened, because if they had the faintest notion of what was going to happen 20 years later (the return from Exile), it would have been included, just as the Chronicler includes it. For the biblical people, the return was the most important event after the destruction. I think the Primary History was written in anticipation of the return from Exile, but before it happened. The Persian king Cyrus, who conquered the Babylonians, issued an edict allowing the Jews to return to their land. No-body predicted that. Afterward, they all claimed to have, but we know it was a total surprise.