Things Get Very Clear When You’re Cornered

An Interview With Chogyam Trungpa

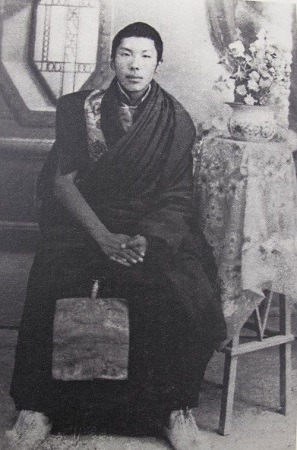

In 1938 the tenth Trungpa Tulku, abbot of Tibet’s Surmang monasteries, died. Shortly thereafter, the Gyalwa Karma pa was shown in a vision the circumstances of Trungpa’s reincarnation. The child was discovered and tested. Offered various objects, he correctly chose those used by him in his previous life. At thirteen months, Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche (“Precious One”) was installed as the new Surmang supreme abbot. After the Communist invasion of Tibet and his escape to India in 1959, Trungpa Rinpoche attended Oxford and founded a Buddhist center in Scotland.

In 1970 he came to the United States and established Nalanda Foundation, which now consists of The Maitri Space Awareness Training Center in Connecticut, the Mudra Theatre Group and Naropa Institute in Colorado, and Vajradhatu, an association of Tibetan Buddhist meditation and retreat centers in nine states and Canada.

Trungpa Rinpoche is a very busy man. After waiting several months for an opportunity to interview him, I received a phone call from his secretary on December 8, 1975, indicating that I could interview him before he left for Vermont on the 12th. Two days later, I was in his office in Boulder setting up tape recording equipment.

Trungpa Rinpoche entered the room so casually it seemed as though he were already in it. There was nothing contrived about him. He wore a Western business suit with a tie and greeted me openly, in a most ordinary and understated way. The only thing that belied his modest manner was a humorous, almost waggish smile. Speaking very softly, he seemed supremely relaxed. His face never showed a trace of concern. As I directed a series of often complex questions to him, Trungpa Rinpoche never became academic or theoretical. He responded directly to the point, and not from memory. His answers seemed to me to be a spontaneous expression of the centuries-old Tibetan wisdom he represents. – Crane Montano

***

THE LAUGHING MAN: What liabilities do Americans, as typical spiritual materialists, face over against a Tibetan’s more natural talent for practicing the Tantric path?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: All Buddhist countries are having political and spiritual difficulties, so practice becomes less important. Some corruptions are taking place. Despite the fact that our country has been completely desecrated, we Tibetans have been very fortunate. A few of us have survived with hot blood, a training and spiritual understanding which will allow Tibetan Buddhism to carry on. Otherwise the whole affair would become slow death. Here in America we are not concerned with adapting across cultural barriers but with handling the teaching here in a skillful way. When Tibetans began to present Buddhism in this country, we did it in keeping with the people’s mentality and language. As people understand it more and more, it begins to take a real traditional form. If we were to present all the heavy traditional stuff at the beginning, then all sorts of fascination with Tibetan culture and enlightenment would take place, and the basic message would be lost. So it is good to start with a somewhat free form and slowly tighten it up. This way people have a chance to absorb and understand.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In your book, Born in Tibet, you described how when you made your own cultural adaptation, taking off the monastic robes and so forth, there were devastating karmic effects in your own life, represented particularly by your severe automobile accident. Do you see any such liability in your continuing work?

THE LAUGHING MAN: In your book, Born in Tibet, you described how when you made your own cultural adaptation, taking off the monastic robes and so forth, there were devastating karmic effects in your own life, represented particularly by your severe automobile accident. Do you see any such liability in your continuing work?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Tibetans generally have to break through the cultural fascinations and mechanized world of the twentieth century. Many Tibetans either hold back completely or try to be extraordinarily cautious, not communicating anything at all. Sometimes they just pay lip-service to the modern world, making an ingratiating diplomatic approach to the West. The other temptation is to regard the new culture as a big joke and to play the game in terms of a conception of Western eccentricities. So we have to break through all of that. I found within myself a need for more compassion for Western students. We don’t need to create imposing images but to speak to them directly, to present the teachings in eyelevel situations. I was doing the same kind of thing that I just described, and a very strong message got through to me: “You have to come down from your high horse and live with them as individuals!” So the first step is to talk with people. After we make friends with students they can begin to appreciate our existence and the quality of the teachings. Later, we can raise the eye-level of the teacher in relation to the students so that they may appreciate the teaching and the teacher as well.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Your writings seem to provide a progressive description of the Guru from a spiritual friend to a more and more intense confrontation with a very high form of function, the Buddha-Mind itself. What is that relationship to the Guru?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: There seem to be traditional approaches at three levels. At the beginning the Guru is known simply as a wise man, a teacher. At that level the student regards the Guru as a kind of parental figure. It is the toilet-training stage; the student is just learning to handle life. Then a relationship develops and the Guru becomes a spiritual friend. At this level he offers encouragement rather than criticism.

In the Vajrayana relationship the Guru is more like a warrior who is trying to show you how to handle your problems, your life, your world, your self, all at the same time. This function of the Guru is very powerful. He has the majestic quality of a king, but at the same time, the power he generates is shared with the student. It is not as if the king is looking down on his subjects as dirty and unworthy peasants. He raises the student’s dignity to a level of healthy arrogance, so to speak. But the most important point is to develop an appreciation of the teachings and not to allow any kind of doubt or hesitation to prevent putting them into practice.

THE LAUGHING MAN: You have indicated that it might take twenty to thirty years before the advanced Vajrayana visualizations could be done in the West. In what practical ways are the foundations of Tantric sadhana established in your present work with students?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Vajrayana is very easy to understand. It is very straight-forward and direct, and it actually speaks to your heart. But just because of its simplicity and directness and power, it might be difficult for people to understand without some kind of preparation. Hinayana practice is valuable because it constantly raises people’s sense of mindfulness. They become more aware and appreciative of the world around them. At the Mahayana level a sense of generosity and warmth is developed. People begin to relate to the world with openness rather than fear. This is necessary preparation for the Vajrayana level. Even in Theravadin countries where Vajrayana is not incorporated into Buddhist teachings, highly accomplished Theravadin students and teachers may also go through a similar kind of journey. We can say that the student of Buddhism is being led ultimately to Vajrayana, whatever form of Buddhism he is practicing.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Are any of your students involved in Vajrayana practice at this time?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: People have to pass through many hours of sitting practice before they are ready for that. But much more important is a sense of dedication and total development in their state of being. At the moment we have something like four hundred committed members here in Boulder, out of which there are about a hundred Tantric students. Those hundred are still at the beginning of the beginnings, so you can’t really call them Tantric practitioners yet.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Is it possible for an American student to pass through the various stages of spiritual development as quickly as someone who is born into the tradition?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Yes and no. Sometimes people born in native Buddhist countries encounter a different kind of cultural obstacle. Either they form a lot of preconceptions about spirituality as they grow up, or the language has become so technical that they have difficulty relating to it. So in some ways I think Americans are more fortunate. The language I use had to be created specifically to translate Buddhist ideas into English in a way that makes real sense to people. So Americans can be free of cultural preconceptions. On the other hand, it is much easier to be led astray if you have no idea where your practice is leading, and you feel completely at the mercy of the teaching or the teacher. So it can be somewhat difficult and tricky.

***

The View of Vajrayana

The essence of the mind of all beings

Is primordially the essence of buddhahood.

Its empty essence is the birthless dharmakaya.

Its clear distinct appearances are the sambhogakaya.

Its unceasing compassion is the variegated nirmanakaya.

The inseparable union of those three is the svabhavikakaya.

Its eternal changelessness is the mahasukhakaya.***

THE LAUGHING MAN: Apart from all the fascinating content, what is the real process that Tantra represents?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: The important thing is what’s known as lineage, not so much the books or traditions handed down. There must be a transformation, some actual experience that people begin to feel. And that is happening all the time. Individuals begin to pick up new experiences from a teacher who has also experienced these things. So there is a meeting of the two minds. This makes the Tantric tradition much more powerful, superior to any other tradition. Tantra doesn’t depend upon any kind of external particularity. It is a very direct experience transmitted from person to person.

THE LAUGHING MAN: A friend once told me about attending a session in which you ceremonially manifested the consciousness of your lineage. Some people had visions of Marpa and Milarepa and he personally felt a rather extraordinary force being communicated. That transmission was obviously a real event in this guy’s life. How is the transmission of the lineage communicated?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Well, I’m rather suspicious about visions of that nature. [Laughs] But in students who are committed I think it is a matter of choicelessness. Choicelessness is having no room to turn around or retrieve anything from the past. Things get very clear when you are cornered but not held captive or imprisoned. When you don’t have any choice you begin to give up. The student probably doesn’t know that he or she is giving up. but something is let go. And when letting go begins to take place there is some of that complete identification with the practice. It is not so much a matter of becoming certain of the truth of Buddhism or Vajrayana as it is the awakening of your own understanding.

At this point, perhaps for the first time in the individual’s life, he begins to realize immense new possibilities. But it is a matter of waking up. You cannot borrow it from somewhere. There is a tremendous sense of richness and power. So the individual becomes appreciative of the teachings and the teacher because they created that situation for him. Even so, it wasn’t done deliberately. It was natural, and that particular event took place.

THE LAUGHING MAN: What has to go on in a person’s life in order for this letting go to be a real event instead of a contrived effort?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: At the beginning of practice even your sitting and meditation on your zafu is a pretense of meditation rather than the real thing. Whatever you do is artificial. ‘There is no starting point except simply doing it. Then you begin to feel all kinds of restlessness. There is subconscious gossip, frustrations, and resentment. But at a certain point you find that you are no longer pretending. You are actually doing it. There is no particular moment in which this change occurs. It is just a process of growing up. You begin to realize that you are immersed in your own neurosis. You cannot really reject it. It is with you. At some point you give up hope of being able to get rid of that. You begin to accept it rather than trying to dispel it. Then something begins to happen. You just have to let go. You give in.

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: At the beginning of practice even your sitting and meditation on your zafu is a pretense of meditation rather than the real thing. Whatever you do is artificial. ‘There is no starting point except simply doing it. Then you begin to feel all kinds of restlessness. There is subconscious gossip, frustrations, and resentment. But at a certain point you find that you are no longer pretending. You are actually doing it. There is no particular moment in which this change occurs. It is just a process of growing up. You begin to realize that you are immersed in your own neurosis. You cannot really reject it. It is with you. At some point you give up hope of being able to get rid of that. You begin to accept it rather than trying to dispel it. Then something begins to happen. You just have to let go. You give in.

THE LAUGHING MAN: In order for that to take place, doesn’t there have to be a certain persistence in the ongoing basic practice?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Definitely. At this point we aren’t talking about intellectual speculation. It has to be a real thing. [Laughs] I don’t speak to people about themselves analytically. I don’t suggest what things should happen to particular people or what is wrong with them personally. In our community we make it very direct: “Get a job.’’ I ask people, “How much are you sitting? What are you studying? Where are you working?’’ I conduct occasional seminars but they do not involve much interpretation or analysis. I try to highlight what students can relate to their own experiences.

THE LAUGHING MAN: I have read about the practice of Tumo which evidently involves higher forms of realization than simply melting snow through the generation of extraordinary body heat. Is this kind of technical, intricate, advanced, and characteristically Tibetan form of yoga something that you see taking place in the West?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: I think so. There is no particular limitation as long as the endurance and devotion of the student continues. There is no reason for the teaching to stop half way through.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Your writings indicate that the Mahamudra is not the highest form of Buddhist realization. Is this because it tends to lock into shunyata as a final experience?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Intuitive realization is the backbone of the whole thing. But intuitive realization of shunyata without any application to the world is helpless. There is no way to grow without it. So those two go hand in hand. Mahamudra is one of the first levels of Tantric spiritual understanding. It was known as the new school of Tantric tradition. We also have an old school in which there is a further understanding, which is called Ati, Maha Ati. In Maha Ati that shunyata experience is brought directly to the manifest world. So that also needs to be applied practically. Tantra is basically defined as continuity, the continuity of play within this world, the dance within this world. So those two, intuitive realization of shunyata and skillful means of application in the world are like the two wings of a bird. You cannot separate them.

THE LAUGHING MAN: The Maha Ati realization is the return to ordinary life in the world rather than relying on that intuitive realization exclusively?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Suppose you have a glimpse of the space inside a cup, and you build larger and larger cups in order to appreciate more spaciousness. Finally, you break the last cup. You know the outside completely. You don’t have to build a cup to understand what space is like. Space is everywhere.

THE LAUGHING MAN: Is this kind of breaking of the cup brought about through any specific visualization?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: The breaking through takes place all the time. There is no particular time or situation. It is like learning how to balance on a bicycle. Nobody can actually tell you how to do it. But you keep on doing it and you keep falling off. And finally you can do it. It is a stroke of genius of some kind. [Laughs]

When one talks about Non-Practice, His mind is still active;

He talks about illumination, But in fact is blind.

In the Stage of Non-Practice, There is no such thing!

—Milarepa

THE LAUGHING MAN: How would you define the ultimate realization of Buddhism?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: I think we have been talking about that, haven’t we? [Laughs] I suppose you could say that there is no such thing as ultimate realization per se. There is no final thing. It happens when you lose your reference point and stop contrasting. But you can’t really talk about it. It is not that it is a terrible thing to say, but just that there is no word for it.

THE LAUGHING MAN: But a characterization can be made. When Christianity contacts the Ultimate, it is spoken of in terms of love. In Hinduism there is Sat-chit-ananda, existence-consciousness-bliss. And within the Buddhist traditions there are various attempts to characterize or not characterize the Ultimate.

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: I think Nagarjuna says it: “I have no philosophy, therefore This is It.” The purpose is not to come to a final conclusion but to try to short-circuit the concept of conclusion altogether. And you can call it “enlightenment,” I suppose. That is a somewhat handy, safe term. [Laughs] . . . Or “awake.”

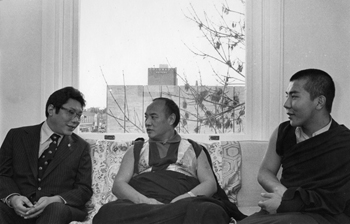

THE LAUGHING MAN: Can you comment on the recent visit of His Holiness Gyalwa Karma-pa to this country?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: His recent visit to America was a very special acknowledgment that American students can receive the teachings of Vajrayana in the fullest sense. He is very excited about the groundwork that has been prepared already. So I think it is a real historical event when a Buddhist leader begins to acknowledge the potential i of Western students. He felt that he could bless them and sow further seeds on the ground we have prepared.

THE LAUGHING MAN: The Dalai Lama has said that he saw Tibetans being reborn in the West as a part of the Dharma taking root here. Do you see Americans carrying on as Tibetans have in past centuries?

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA: Not only that. Eventually Americans can go back to Tibet and teach Buddhism in that country. A similar situation exists in certain Theravadin countries like Thailand and Sri Lanka [Ceylon] where many of the best exponents of Buddhism are Western bhik-kus. So anything is possible!