Wisdom Goddesses : Mahavidyas and the Assertion of Femininity in Indian Thought

There exists in India a group

of strange Goddesses, ten in number. One of them

is shown holding her own freshly severed head,

which feeds on the blood flowing from her headless

torso; another holds a pair of scissors while

sitting triumphant atop a corpse;

|

|

a third is depicted as an old

and ugly widow riding a chariot decorated with

the crow as an emblem. The series continues –

an unusual assemblage to say the least.

|

|

The

The

story behind their birth is equally interesting

and paradoxically of a romantic origin:

Once during their numerous

love games, things got out of hand between Shiva

and Parvati. What had started in jest turned into

a serious matter with an incensed Shiva threatening

to walk out on Parvati. No amount of coaxing or

cajoling by Parvati could reverse matters. Left

with no choice, Parvati multiplied herself into

ten different forms for each of the ten directions.

Thus however hard Shiva might try to escape from

his beloved Parvati, he would find her standing

as a guardian, guarding all escape routes.

Each of the Devi’s manifested

forms made Shiva realize essential truths, made

him aware of the eternal nature of their mutual

love and most significantly established for always

in the cannons of Indian thought the Goddess’s

superiority over her male counterpart. Not that

Shiva in any way felt belittled by this awareness,

only spiritually awakened. This is true as much

for this Great Lord as for us ordinary mortals.

Befittingly thus they are referred to as the Great

Goddess’s of Wisdom, known in Sanskrit as the

Mahavidyas (Maha – great; vidya – knowledge).

Indeed in the process of spiritual learning the

Goddess is the muse who guides and inspires us.

She is the high priestess who unfolds the inner

truths.

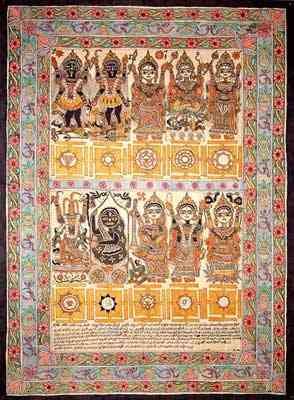

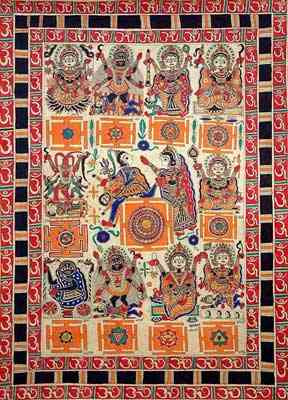

The spectrum of these ten goddesses

covers the whole range of feminine divinity, encompassing

horrific goddess’s at one end, to the ravishingly

beautiful at the other. These Goddesses are:

1) Kali the Eternal Night

2) Tara the Compassionate Goddess

3) Shodashi the Goddess who is Sixteen Years Old

4) Bhuvaneshvari the Creator of the World

5) Chinnamasta the Goddess who cuts off her Own

Head

6) Bhairavi the Goddess of Decay

7) Dhumawati the Goddess who widows Herself

8) Bagalamukhi the Goddess who seizes the Tongue

9) Matangi the Goddess who Loves Pollution

10) Kamala the Last but Not the Least

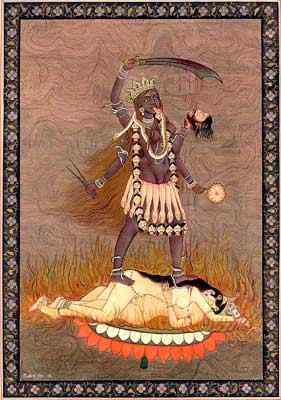

Kali the Eternal Night

Kali

Kali

is mentioned as the first amongst the Mahavidyas.

Black as the night she has a terrible and horrific

appearance.

In the Rig-Veda, the world’s

most ancient book there is a ‘Hymn to the Night’

(Ratri sukta), which says that there are two types

of nights. One experienced by mortal beings and

the other by divine beings. In the former all

ephemeral activity comes to a standstill, while

in the latter the activity of divinity also comes

to rest. This absolute night is the night of destruction,

the power of kala. The word kala denotes time

in Sanskrit. Kali’s name is derived from this

word itself, as also from the Sanskrit word for

black. She is thus the timeless night, both for

ordinary mortals and for divine beings. At night

we nestle in happiness like birds in their nests.

Dwellers in the villages, theirs cows and horses,

the birds of the air, men who travel on many a

business, and jackals and wild beasts, all welcome

the night and joyfully nestle in her; for to all

beings misguided by the journey of the day she

brings calm and happiness, just as a mother would.

The word ratri (night) is derived from the root

ra, “to give,” and is taken to mean

“the giver” of bliss, of peace of happiness.

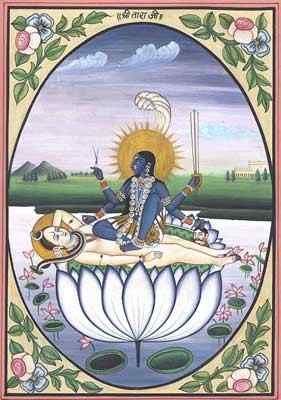

Tara the Compassionate Goddess

The similarities in appearance

between Kali and Tara are striking and unmistakable.

They both stand upon a supine male figure often

recognizable as Shiva but which may also be an

anonymous corpse.

Both wear minimal clothing

or are naked. Both wear a necklace of freshly

severed heads and a girdle of human hands. Both

have a lolling tongue, red with the blood of their

victims. Their appearances are so strikingly similar

that it is easy to mistake one for the other.

The oral tradition gives an

intriguing story behind the Goddess Tara. The

legend begins with the churning of the ocean.

Shiva has drunk the poison that was created from

the churning of the ocean, thus saving the world

from destruction, but has fallen unconscious under

its powerful effect. Tara appears and takes Shiva

on her lap. She suckles him, the milk from her

breasts counteracting the poison, and he recovers.

This myth is reminiscent of the one in which Shiva

stops the rampaging Kali by becoming an infant.

Seeing the child, Kali’s maternal instinct comes

to the fore, and she becomes quiet and nurses

the infant Shiva. In both cases, Shiva assumes

the position of an infant vis-à-vis the

goddess. In other words the Goddess is Mother

even to the Great Lord himself.

The distinguishing feature

in Tara’s iconography is the scissors she holds

in one of her four hands. The scissors relate

to her ability to cut off all attachments.

Literally the word ‘tara’ means

a star. Thus Tara is said to be the star of our

aspiration, the muse who guides us along the creative

path. These qualities are but a manifestation

of her compassion. The Buddhist tradition stresses

these qualities of this Goddess, and she is worshipped

in Tibet as an important embodiment of compassion.

Shodashi the Goddess who is Sixteen Years Old

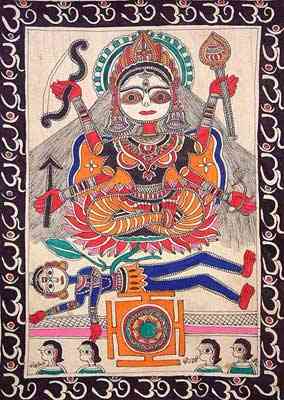

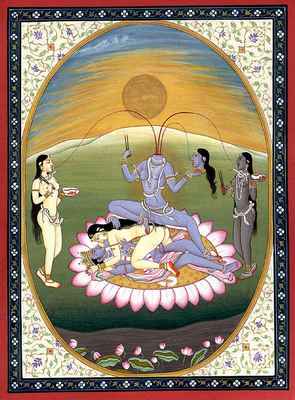

Shodashi

Shodashi

or Tripura-Sundari is believed to have taken birth

to save the gods from the ravages of a mighty

and wrathful demon. The tale begins when Shiva

burnt down Kama, the god of love, who tried to

distract Shiva from his meditation. One of Shiva’s

followers then scooped off Kama’s ashes and formed

the image of a man out of them. This man then

persuades Shiva to teach him a powerful mantra.

By the power of this mantra, one could gain half

the might of one’s adversary. But because he was

generated from the ashes of Shiva’s wrath he is

transformed into a fierce demon. Intoxicated with

his new found power he proceeded to rampage the

kingdom of the gods. Apprehending defeat and humiliation,

the gods all propitiate Goddess Tripura-Sundari

to seek her help. The goddess appears and agrees

to help them. Taking the battlefield she heaps

a crushing blow on the mighty demon, thus saving

the gods.

Iconographically this Goddess

is shown seated on a lotus that rests on the supine

body of Lord Shiva, who in turn lies on a throne

whose legs are the gods Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva,

and Rudra.

This is a direct and hard-hitting

portrayal of the Goddess dominating the important

male deities of the Hindu pantheon, a central

belief of the Mahavidya ideology. She is the savior

of all, the Last Refuge.

She holds in her hands a pair

of bow and arrows. The bow significantly is made

of sugarcane, a symbol of sweetness. Her darts

thus are sweetness personified. One of her epithets

is ‘Tripura-Sundari,’ meaning ‘One who is beautiful

in the three realms.’ Another of her names ‘Lalita’

implies softness. These two qualities give rise

to images that depict her as ravishingly beautiful

and of unsurpassed splendor.

The word ‘Shodashi’ literally

means sixteen in Sanskrit. She is thus visualized

as sweet girl of sixteen. In human life sixteen

years represent the age of accomplished perfection

after which decline sets in. Indeed sixteen days

form the completed lunar cycle from the new moon

to the full moon. The full moon is the moon of

sixteen days. This girl of sixteen rules over

all that is perfect, complete, beautiful. Her

supreme beauty too has an interesting story behind

it:

Once upon a time Shiva referred

to Kali (his wife) by her name in front of some

heavenly damsels who had come to visit, calling

her “Kali, Kali” (“Blackie, Blackie”)

in jest. This she took to be a slur against her

dark complexion. She left Shiva and resolved to

rid herself of her dark complexion, through asceticism.

Later, the sage Narada, seeing Shiva alone, asked

where his wife was. Shiva complained that she

had abandoned him and vanished. With his yogic

powers Narada discovered Kali living north of

Mount Sumeru and went there to see if he could

convince her to return to Shiva. He told her that

Shiva was thinking of marrying another goddess

and that she should return at once to prevent

this. By now Kali had rid herself of her dark

complexion but did not yet realize it. Arriving

in the presence of Shiva, she saw a reflection

of herself with a light complexion in Shiva’s

heart. Thinking, that this was another goddess,

she became jealous and angry. Shiva advised her

to look more carefully, with the eye of knowledge,

telling her that what she saw in his heart was

herself. The story ends with Shiva saying to the

transformed Kali: “As you have assumed a

very beautiful form, beautiful in the three worlds,

your name will be Tripura- Sundari. You shall

always remain sixteen years old and be called

by the name Shodashi.”

Bhuvaneshvari

Bhuvaneshvari

the Creator of the World

A modern text gives the legend

of origin of Bhuvaneshvari as follows:

‘Before anything existed it

was the sun which appeared in the heavens. The

rishis (sages) offered soma the sacred plant to

it so that the world may be created. At that time

Shodashi was the main power, or the Shakti through

whom the Sun created the three worlds. After the

world was created the goddess assumed a form appropriate

to the manifested world.’

In this form she came to be

known as Bhuvaneshvari, literally ‘Mistress of

the World.’

Bhuvaneshvari thus remains

un-manifest until the world is created. Hence

she is primarily related with the visible and

material aspect of the created world.

More than any other Mahavidya

with the exception of Kamala (mentioned later),

Bhuvaneshvari is associated and identified with

the energy underlying creation. She embodies the

characteristic dynamics and constituents that

make up the world and that lend creation its distinctive

character. She is both a part of creation and

also pervades it’s aftermath.

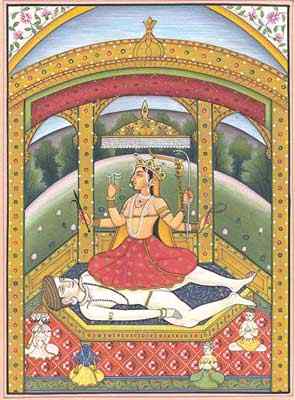

Bhuvaneshvari’s

Bhuvaneshvari’s

beauty is mentioned often. She is described as

having a radiant complexion and a beautiful face,

framed with flowing hair the color of black bees.

Her eyes are broad, her lips full and red, her

nose delicate. Her firm breasts are smeared with

sandal paste and saffron. Her waist is thin, and

her thighs, buttocks, and navel are lovely. Her

beautiful throat is decorated with ornaments,

and her arms are made for embracing. Indeed Shiva

is said to have produced a third eye to view her

more thoroughly.

This beauty and attractiveness

may be understood as an affirmation of the physical

world. Tantric thought does not denigrate the

world or consider it illusory or delusory, as

do some other abstract aspects of Indian thought.

This is made amply clear in the belief that the

physical world, the rhythms of creation, maintenance

and destruction, even the hankerings and sufferings

of the human condition is nothing but Bhuvaneshvari’s

play, her exhilarating, joyous sport.

Chinnamasta the Goddess who cuts off her Own

Head

One day Parvati went to bathe

in the Mandakini River with her two attendants,

Jaya and Vijaya. After bathing, the great goddess’s

color became black because she was sexually aroused.

After some time, her two attendants asked her,

“Give us some food. We are hungry.”

She replied, “I shall give you food but please

wait.” After awhile, again they asked her.

She replied, “Please wait, I am thinking

about some matters.” Waiting awhile, they

implored her, “You are the mother of the

universe. A child asks everything from her mother.

The mother gives her children not only food but

also coverings for the body. So that is why we

are praying to you for food. You are known for

your mercy; please give us food.” Hearing

this, the consort of Shiva told them that she

would give anything when they reached home. But

again her two attendants begged her, “We

are overpowered with hunger, O Mother of the Universe.

Give us food so we may be satisfied, O Merciful

One, Bestower of Boons and Fulfiller of Desires.”

Hearing

Hearing

this true statement, the merciful goddess smiled

and severed her own head. As soon as she severed

her head, it fell on the palm of her left hand.

Three bloodstreams emerged from her throat; the

left and right fell respectively into the mouths

of her flanking attendants and the center one

fell into her mouth.

After performing this, all

were satisfied and later returned home. (From

this act) Parvati became known as Chinnamasta.

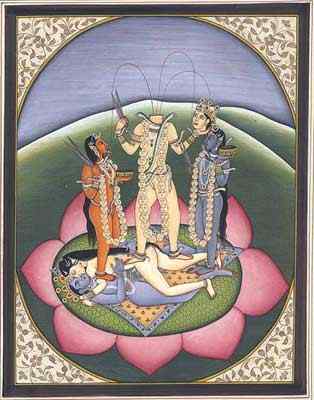

In visual imagery, Chinnamasta

is shown standing on the copulating couple of

Kamadeva and Rati, with Rati on the top. They

are shown lying on a lotus.

There are two different interpretations

of this aspect of Chinnamasta’s iconography. One

understands it as a symbol of control of sexual

desire, the other as a symbol of the goddess’s

embodiment of sexual energy.

The most common interpretation

is one where she is believed to be defeating what

Kamadeva and Rati represent, namely sexual desire

and energy. In this school of thought she signifies

self-control, believed to be the hallmark of a

successful yogi.

The

The

other, quite different interpretation states that

the presence of the copulating couple is a symbol

of the goddess being charged by their sexual energy.

Just as a lotus seat is believed to confer upon

the deity seated atop it’s qualities of auspiciousness

and purity, Kamadeva and Rati impart to the Goddess

standing over them the power and energy generated

by their lovemaking. Gushing up through her body,

this energy spouts out of her headless torso to

feed her devotees and also replenish herself.

Significantly here the mating couple is not opposed

to the goddess, but an integral part of the rhythmic

flow of energy making up the Chinnamasta icon.

The image of Chinnamasta is

a composite one, conveying reality as an amalgamation

of sex, death, creation, destruction and regeneration.

It is stunning representation of the fact that

life, sex, and death are an intrinsic part of

the grand unified scheme that makes up the manifested

universe. The stark contrasts in this iconographic

scenario-the gruesome decapitation, the copulating

couple, the drinking of fresh blood, all arranged

in a delicate, harmonious pattern – jolt the viewer

into an awareness of the truths that life feeds

on death, is nourished by death, and necessitates

death and that the ultimate destiny of sex is

to perpetuate more life, which in turn will decay

and die in order to feed more life. As arranged

in most renditions of the icon, the lotus and

the pairing couple appear to channel a powerful

life force into the goddess. The couple enjoying

sex convey an insistent, vital urge to the goddess;

they seem to pump her with energy. And at the

top, like an overflowing fountain, her blood spurts

from her severed neck, the life force leaving

her, but streaming into the mouths of her devotes

(and into her own mouth as well) to nourish and

sustain them. The cycle is starkly portrayed:

life (the couple making love), death (the decapitated

goddess), and nourishment (the flanking yoginis

drinking her blood).

Bhairavi the Goddess of Decay

Creation

Creation

and Destruction are two essential aspects of the

universe, which is continually subject to their

alternating rhythms. The two are equally dominant

in the world and indeed depend upon each other

in symbiotic fashion. Bhairavi embodies the principle

of destruction and arises or becomes present when

the body declines and decays. She is also evident

in self-destructive habits, such as eating tamsic

food (food having a quality associated with ignorance

and lust) and drinking liquor, which wear down

the body and mind. She is present, it is said,

in the loss of semen, which weakens males. Anger,

jealousy, and other selfish emotions and actions

strengthen Bhairavi’s presence in the world. Righteous

behavior, conversely, makes her weaker. In short,

she is an ever-present goddess who manifests herself

in, and embodies, the destructive aspects of the

world. Destruction, however, is not always negative,

creation cannot continue without it. This is most

clear in the process of nourishment and metabolism,

in which life feeds on death; creation proceeds

by means of transformed energy given up in destruction.

Bhairavi is also identified

with Kalaratri, a name often associated with Kali

that means “black night (of destruction)”

and refers to a particularly destructive aspect

of Kali.

She is also identified with

Mahapralaya, the great dissolution at the end

of a cosmic cycle, during which all things, having

been consumed with fire, are dissolved in the

formless waters of procreation. She is the force

that tends toward dissolution. This force, furthermore,

which is actually Bhairavi herself, is present

in each person as one gradually ages, weakens

and finally dies. Destruction is apparent everywhere,

and therefore Bhairavi is present everywhere.

A commentary on the Parashurama-kalpasutra

says that the name Bhairavi is derived from the

words bharana (to create), ramana (to protect),

and vamana (to emit or disgorge). The commentator,

that is, seeks to discern the inner meaning of

Bhairavi’s name by identifying her with the cosmic

functions of creation, maintenance, and destruction.

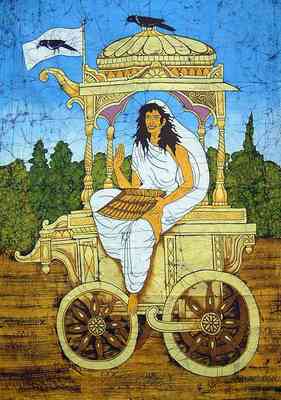

Dhumawati the Goddess

who widows Herself

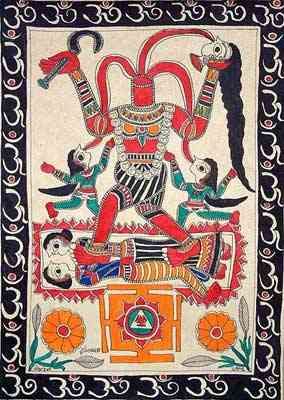

Dhumawati

Dhumawati

is ugly, unsteady, and angry. She is tall and

wears dirty clothes. Her ears are ugly and rough,

she has long teeth, and her breasts hang down.

She has a long nose. She has the form of a widow.

She rides in a chariot decorated with the emblem

of the crow. Her eyes are fearsome, and her hands

tremble. In one hand she holds a winnowing basket,

and with the other hand she makes the gesture

of conferring boons. Her nature is rude. She is

always hungry and thirsty, and looks unsatisfied.

She likes to create strife, and she is always

frightful in appearance.

The legend behind Dhumawati’s

origin says that once, when Shiva’s spouse Sati

was dwelling with him in the Himalayas, she became

extremely hungry and asked him for something to

eat. When he refused to give her food, she said,

“Well, then I will just have to eat you.”

Thereupon she swallowed Shiva, thus widowing herself.

He persuaded her to disgorge him, and when she

did so he cursed her, condemning her to assume

the form of the widow Dhumawati. This myth underlines

Dhumawati’s destructive bent. Her hunger is only

satisfied when she consumes Shiva, her husband

and who contains within himself the whole world.

Ajit Mookerjee, commenting on her perpetual hunger

and thirst, which is mentioned in many places,

says that she is the embodiment of “unsatisfied

desires.” Her status as a widow itself is

curious. She makes herself one by swallowing Shiva,

an act of self-assertion, and perhaps independence.

The

The

crow, which appears as her emblem atop her chariot,

is a carrion eater and symbol of death. Indeed,

she herself is sometimes said to resemble a crow.

The Prapancasarasara-samgraha, for example, says

that her nose and throat resemble those of a crow.

The winnowing basket in her

hand represents the need to discern the inner

essence from the illusory realities of outer forms.

The dress she wears has been taken from a corpse

in the cremation ground. She is said to be the

embodiment of the tamas guna, the negative qualities

associated with lust and ignorance. She is believed

to enjoy liquor and meat, both of which are tamsic.

Dhumawati is also interpreted by some Tantra scholars

as “the aspect of reality that is old, ugly,

and unappealing. This is further corroborated

by the fact that she is generally associated with

all that is inauspicious and is believed to dwell

in desolate areas of the earth, such as deserts,

in abandoned houses, in quarrels, in mourning

children, in hunger and thirst, and most particularly

in widows.

Bagalamukhi the Goddess who seizes the Tongue

The legend behind the origin

of goddess Bagalamukhi is as follows:

A demon named Madan undertook

austerities and won the boon of vak siddhi, according

to which anything he said came about. He abused

this boon by harassing innocent people. Enraged

by his mischief, the gods worshipped Bagalamukhi.

She stopped the demon’s rampage by taking hold

of his tongue and stilling his speech. Before

she could kill him, however, he asked to be worshipped

with her, and she relented, That is why he is

depicted with her. She is almost always portrayed

in this act, holding a club in one hand, with

which she is about to strike her enemy, and with

the other hand pulling his tongue. In this myth,

by stopping the demon’s tongue, she exercises

her peculiar power over speech and her power to

freeze, stun, or paralyze.

The pulling of the demon’s

tongue by Bagalamukhi is both unique and significant.

Tongue, the organ of speech and taste, is often

regarded as a lying entity, concealing what is

in the mind. The Bible frequently mentions the

tongue as an organ of mischief, vanity and deceitfulness.

The wrenching of the demon’s tongue is therefore

symbolic of the Goddess removing what is in essentiality

a perpetrator of evil.

Matangi the Goddess who Loves Pollution

Once Parvati, seated on Shiva’s

lap, said to him that he always gave her anything

she wanted and that now she had a desire to visit

her father. Would he consent to her visiting her

father, Himalaya, she asked? Shiva was not happy

about granting her this wish but eventually complied,

saying that if she did not come back in a few

days, he would go there himself to ask for her

return. Parvati’s mother sent a crane to carry

Parvati back to her family home. When she did

not return for some days, Shiva disguised himself

as an ornament maker and went to her father’s

house. He sold shell ornaments to Parvati and

then, seeking to test her faithfulness, asked

that she have sex with him as his payment. Parvati

was outraged at the merchant’s request and was

ready to curse him, but then she discerned with

her yogic intuition that the ornament vendor was

really her husband, Shiva. Concealing her knowledge

of his true identity, she replied: “Yes,

fine, I agree. But not just now.”

Sometime later, Parvati disguised

herself as a huntress and went to Shiva’s home,

where he was preparing to do evening prayer. She

danced there, wearing red clothes. Her body was

lean, her eyes wide, and her breasts large. Admiring

her, Shiva asked: “Who are you?” She

replied: “I am the daughter of a Chandala.

I’ve come here to do penance.” Then Shiva

said: “I am the one who gives fruits to those

who do penance.” Saying this, he took her

hand, kissed her, and prepared to make love to

her. While they made love, Shiva himself was changed

into a Chandala. At this Point he recognized the

Chandala woman as his wife Parvati. After they

had made love, Parvati asked Shiva for a boon,

which he granted. Her request was this: “As

you [Shiva] made love to me in the form of a Chandalini

[Chandala woman], this form should last forever

and be known as Uccishtha-matangini (now popularly

known as Matangi).”

The key to this legend is the

essence of the word ‘Chandala.’ The Chandalas

are believed to constitute the lowest strata of

the caste hierarchy in orthodox Hindu belief.

Associated with death and impurity they have always

survived on the fringes of mainstream society.

Derogatory in the extreme sense, The label chandala

itself has become the worst kind of slur. Thus

by disguising herself as a Chandalini, Parvati

assumes the identity of a very low-caste person,

and by being attracted, Shiva allows himself to

be identified with her. Both deities self-consciously

and willingly associate themselves with the periphery

of Hindu society and culture. The Chandala identity

is sacralized therefore, in the establishment

of Goddess Matangi. This goddess summarizes in

herself the polluted and the forbidden.

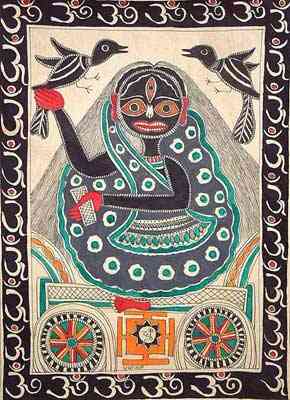

Another

Another

myth related to Matangi reinforces this belief.

Once upon a time, Vishnu and Lakshmi went to visit

Shiva and Parvati. They gifted Shiva and Parvati

fine foods, and some pieces dropped to the ground.

From these remains arose a maiden endowed with

fair qualities. She asked for leftover food (uccishtha).

The four deities offered her their leftovers as

prasada (food made sacred by having been tasted

by deities). Shiva then said to the attractive

maiden: “Those who repeat your mantra and

worship you, their activities will be fruitful.

They will be able to control their enemies and

obtain the objects of their desires.” From

then on this maiden became known as Uccishtha-matangini.

She is the bestower of all boons.

This legend stresses Matangi’s

association with leftover food, which is normally

considered highly polluting. Indeed, she herself

actually arises or emerges from Shiva and Parvati’s

table scraps. And the first thing she asks for

is sustenance in the form of leftover food (uccishtha).

Texts describing her worship specify that devotees

should offer her uccishtha with their hands and

mouths stained with leftover food; that is, worshippers

should be in a state of pollution, having eaten

and not washed. This is a dramatic reversal of

the usual protocols for the worship of deities.

Normally, devotees are careful to offer particularly

pure food or food that the deity especially likes.

After the deity has eaten it, the food is thought

of as blessed and returned to the worshipper to

partake, and is believed to contain the grace

of the deity. The ritual give-and-take in this

case emphasizes the inferior position of the devotee,

who serves the deity and accepts the deity’s leftover

food as something to be cherished. In the case

of Matangi however, worshippers present her with

their own highly polluted leftover food and are

themselves in a state of pollution while doing

so.

In some rituals she is known

to have been offered a piece of clothing stained

with the menstrual blood in order to win the boon

of being able to attract someone. Menstrual blood

is regarded as taboo in the performance of religious

functions, but in the case of Matangi these strict

taboos are disregarded, indeed, are flaunted.

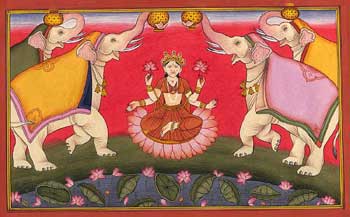

Kamala

Kamala

the Last but Not the Least

Kamala as the tenth and last

of the Wisdom Goddesses shows the full unfoldment

of the power of the Goddess into the material

sphere. She is both the beginning and the end

of our worship of the goddess.

The canonical texts are quite

specific regarding her iconography:

‘She has a beautiful and golden

complexion. She is being bathed by four large

elephants who pour jars of nectars over her. In

her four hands she holds two lotuses and makes

the signs of granting boons and giving assurance.

She wears a resplendent crown and a silken dress.’

The name Kamala means “she

of the lotus” and is a common epithet of

Goddess Lakshmi. Indeed, Kamala is none other

than the goddess Lakshmi. Though listed as the

last of the Mahavidyas, she is the best known

and most popular. Several annual festivals are

given in her honor. Of these, the Diwali festival

is most widely celebrated. This festival links

Lakshmi to three important and interrelated themes:

prosperity and wealth, fertility and crops, and

good luck during the coming year.

The elephants pouring nectar

onto her are symbols of sovereignty and fertility.

They convey Kamala’s association with these highly

desirable qualities.

Though equivalent to Lakshmi,

important differences exist when Kamala is included

in the group of Mahavidyas. Most strikingly, she

is never described or shown accompanying Vishnu,

who otherwise is her constant and dominating companion

in all representations.

In this

respect unlike Lakshmi, Kamala is almost entirely

removed from marital and domestic contexts. She

does not play the role model of a wife in any

way, and her association with proper dharmic or

social behavior, either as an example of it or

as the rewarder of it, is not important in the

Mahavidya context. Here a premium seems to be

put on the independence of the goddesses. For

the most part, the Mahavidyas are seen as powerful

goddesses in their own right. Their power and

authority do not derive from association with

male deities. Rather, it is their power that pervades

the gods and enables them to perform their cosmic

functions. When male deities are shown, they are

almost in supporting roles (literally as when

they are shown supporting Shodashi’s throne),

and are depicted as subsidiary figures.

Conclusion

It

It

is striking how female imagery and women are central

to the conception of the Mahavidyas. Iconographically,

they are individually shown dominating male deities.

Kali and Tara are shown astride Shiva, while others

like Shodashi sit on the body of Shiva which in

turn rests upon a couch whose legs are four male

deities! Most significantly none of the Mahavidyas

is shown as the traditional wife or consort. Even

Lakshmi, who is widely known for her position

as Vishnu’s loyal wife is shown alone. It is also

noteworthy that the severed heads that decorate

the goddess’s bodies are male, as are the corpses

that lie beneath them.

Moreover, related Tantric texts

often mention the importance of revering women.

The Kaulavali Tantra says that all women should

be looked upon as manifestations of Mahadevi (the

Great Goddess). The Nila-tantra says that one

should desert one’s parents, guru, and even the

deities before insulting a woman.

Finally the question remains:

Why would one wish to worship a goddess such as

Kali, Chinnamasta, Dhumawati, Bhairavi, or a Matangi,

each of whom dramatically embodies marginal, polluting,

or socially subversive qualities? These goddesses

are both frightening and dangerous. They often

threaten social order. In their strong associations

with death, violence, pollution, and despised

marginal social roles, they call into question

such normative social “goods” as worldly

comfort, security, respect, and honor. The worship

of these goddesses suggests that the devotee experiences

a refreshing and liberating spirituality in all

that is forbidden by established social orders.

The central aim here according

to Tantric belief is to stretch one’s consciousness

beyond the conventional, to break away from approved

social norms, roles, and expectations. By subverting,

mocking, or rejecting conventional social norms,

the adept seeks to liberate his or her consciousness

from the inherited, imposed, and probably inhibiting

categories of proper and improper, good and bad,

polluted and pure.

Living one’s life according

to rules of purity and pollution and caste and

class that dictate how, where, and exactly in

what manner every bodily function may be exercised,

and which people one may, or may not, interact

with socially, can create a sense of imprisonment

from which one might long to escape. Perhaps the

more marginal, bizarre, “outsider” goddesses

among the Mahavidyas facilitate this escape. By

identifying with the forbidden or the marginalized,

an adept may acquire a new and refreshing perspective

on the cage of respectability and predictability.

Indeed a mystical adventure, without the experience

of which, any spiritual quest would remain incomplete.

References and Further Reading

- Danielou, Alain. The

Myths and Gods of India: Vermont, 1991. - Frawley, David. Tantric

Yoga and The Wisdom Goddesses: Delhi, 1999. - Jansen, Eva Rudy.

The Book of Hindu Imagery, The Gods and their

Symbols: Holland, 1998. - Kinsley, David. Tantric

Visions of the Divine Feminine: New Delhi,1997. - Walker, Benjamin.

Encyclopedia of Esoteric Man: London, 1977

This article by Nitin Kumar – Exotic India

|

|

|

images not loading? | error messages? | broken links? | suggestions? | criticism?

contact me

page uploaded 12 July 2004