Re-Enchantment

Jeffrey Paine

LAMA YESHE COULD TRANSPORT the wounded figure of Tibetan Buddhism only so far. He did master new worlds, but not completely. He never fully mastered a Western language. In his one-of-a-kind English when he spoke of a warm peeling,” for example, his students felt the warmth of his feelings before they deciphered the actual words. Like his English, his whole mode of being testified to a transitional figure, made in Tibet but responsive to the West. Uncorrupted, uncompromised, untroubled by spiritual doubt, it could be said that LamaYeshe was in the West but not really of it. He commuted to America and Europe, and died in California, but he never actually experienced what it was to make a home, a life, in a modern Euro-Americanized country.

There was another lama who did, however, inhabit America, and he carried Tibetan Buddhism into the heart of its culture. He identified with America, spoke its slang, and used Made-in-USA references when teaching. He dismissed other lamas who lacked his popular appeal as those ethnic Tibetans.” Unlike LamaYeshe’s, his tale involved both good and evil, a tale in which he was both exemplar and outrage. This other Tibetan demonstrates what happens when one extricates the dharma from its traditional setting and relocates it in unheard-of and compromised realities.

Only a few years after Zina Rachevsky ferreted Lama Yeshe out of his hut in India, Chogyam Trungpa began living and teaching in America. In the story of Tibetan Buddhism in the West, 1970 is an almost prehistoric date. Had you ransacked America, you would have uncovered scant interest or materials (except for Alexandra David-Neels books) about Tibetan Buddhism. By that decade’s end, however, the religion was firmly entrenched. It was a human whirlwind who wrought this change, but at first glance Trungpa looked so unimpressive he was often mistaken for a little Chinese man in a business suit.

It all happened so quickly. In little more than a decade, Trungpa founded nearly a hundred Tibetan Buddhist centers. His books were selling hundreds of thousands of copies. He gave thousands of lectures, attended by such numbers that ah together they would populate a middle- sized city. Some in his audience went on to become his students, doing practices (e.g., the hundred thousand prostrations) once dismissed as fables from the East. He established the first, and only, accredited Buddhist university in the United States. Well-known writers and artists flocked around him, likes bees to a pungent new honey.

His contrast to Lama Yeshe could hardly have been more startling. Lama Yeshe’s vision was essentially a historical:The essence of Tibetan Buddhism was timeless and placeless, not confined to Tibet or even to Buddhism. This ancient religion, Lama Yeshe believed, if presented skillfully, could make itself happily at home in the modern world. Trungpa thought such a happy vision ludicrous: Modernity is too different, and in it true spirituality may disintegrate into inconsequentiality. One cannot stand outside modernity, he held, with a pure and monkish idea of religion, and hope to affect anything. He handed back his lama’s robes, so that no outward sign would distinguish him and no monastic safety net would cushion him from what he called the dance of life.” He would sound the pure Tibetan Vajrayana but in a new and different medium—like, say, a classical theme played on a jazz trombone.

Yet what is peculiar is that even a well-stocked library contains almost nothing written about Trungpa personally. No one accuses him of being a fraud, but the little so far in print paints him as something of a rogue. His many devoted and intelligent students could rebut the insinuations made against him or at least put them into context of his greater achievement, ^ut ^is especially peculiar—for the two decades since his early death, they have shied away from doing so.

Peculiarity is the leitmotif of his biography, running from his birth to his death. In old Tibet a few infants were selected by signs and by omens Trungpa was one such child—to be raised, from infancy on, in perhaps the most rigorous religious education ever devised. The goal of that education was to create persons as close as possible to living Buddhas: perfect in happiness, understanding, and compassion. Here, then, is a plot-idea about innocence and experience that Henry James might have relished: Shanghai someone of such understanding from that rustic world and plop him down in the mad traffic of contemporary America. Who could prophesy what would come of it? Unless, that is, Nietzsche had already predicted it: Someone today with true understanding would be like a god, Nietzsche wrote, “but a god trapped in the stomach of a beast.”

FOR ANYONE INVOLVED WITH Buddhism or spiritual matters in the 1970s, to have met Chogyam Trungpa was probably easier than not to have. He seemed to pop up everywhere.

“Hey, this Tibetan guru is speaking here tonight. Wanna go?”

The young woman, a college student, thought the offer over and then answered, “Hell, no!” For good measure she added, “That’s the last thing I’d want to do.” In her mind she pictured an obscenely (and obscene) fat

charlatan, spouting an Asiatic mumbo jumbo that was supposed to be the word of God. Or suppose he did make sense, so much the worse—then you’d have to become his devotee, and your life would never be your own again. “What’s he like, anyway?”

“They say he plays Monopoly and drinks Colt 45.”

Oh. That wasn’t too mystical or weird.The year was 1972; the city was Los Angeles; and Chogyam Trungpa was speaking that night near UCLA. The two young women arrived early to get good seats, watching the auditorium fill to capacity as folks waited to hear a wise man from the East. And waited. And waited. Trungpa habitually arrived a good hour or two tardy for his talks. When he finally showed up that evening, an almost visible shock rippled through the audience. On each of his arms hung a nymphet in a miniskirt, and he clapped a bottle of Scotch down on the lectern. Our young woman in the first row could not stop laughing. Proof, she thought, just like that, he’s exploded everybody’s image of a holy man. (If that wasn’t his goal, she reasoned, he would have told his nymphets to wait offstage and camouflaged the booze.)

Once Trungpa began speaking, the audience’s expectation of an Oriental Wizard of Oz further evaporated. His talk eschewed magic and mystery in Tibet and instead he used familiar situations recognizable from their jobs or from popular entertainments. Certain difficult Buddhist concepts (e.g., “emptiness’or “nonduality ) had proved all but impossible to present adequately to Westerners, yet most of that audience didn’t t even realize he was presenting them as he found equivalents in English slang. Nor did he repeat the standard Tibetan precept to treat all sentient beings as though they had once been your mother. Trungpa knew many Americans hated their mothers.

In rendering ancient Tibetan Buddhism into ordinary English and modern psychology, Trungpa may have performed as dexterous a feat as exists in the history of translation. Half a thousand years it had taken to transplant Buddhism from India into the old warrior society of Tibet. Chogyam Trungpa was using all his ingenuity to retransmit it to America that very evening. Over the course of many such talks, many such evenings and regardless of the controversies elsewhere in his life—his success in doing so puts ordinary dreams of triumph to shame.

LET US RETURN FOR a moment to his beginnings. As a boy Trungpa often dreamed of trucks and airplanes. That sounds hardly unusual, but he had never seen, not even in a picture, a plane or truck. He described these unheard-of contraptions to his teacher, who dismissed them: Oh, its just nonsense!” Almost everything a contemporary American knows would have seemed just that—nonsense, fantasy—to an old Tibetan. Everything we take for granted, from the moment when the alarm clock goes off and we jump into the shower, to cooking breakfast on the stove or microwave as the phone rings, until the last thing at night when we turn off the computer or TV, would have seemed a magical trick to that boy growing up in remote Tibet.

Yet his peculiar upbringing in Tibet did prepare him for the unexpected. When Chogyam Trungpa was born in February of 1939, a huge rainbow arched over his birthplace (near a tiny village called Geje). His mothers relatives all reported having the same dream, that a lama had entered their nomad s tent that night. Not long thereafter a search began to find the reincarnation of a deceased high lama, the Tenth Trungpa. The great Sixteenth Karmapa had a vision of a village that sounded like Ge-de, and the baby s parents names were . . . and here the Karmapa spelled out in his vision Chogyam’s mother and father’s names. When after months of trial and error the search party arrived in Geje, the small boy unerringly picked out objects once belonging to the Tenth Trungpa, as though they were being returned to him.

As the new Eleventh Trungpa, before he was six years old, Chogyam was studying from five in the morning till eight at night. By age eight he had gone on monthlong meditation retreats. By age twelve he had accomplished the preliminary practices, the ngondro, with its hundred thousand prostrations, hundred thousand mantra recitations, etc., which are said to make body and mind supple. His teachers were legendary figures in Tibet, Jamgon Kongtrul and Dilgo Khyentse—rather like a physics student having for his freshman instructors Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Jamgon Kongtrul had a premonition that darkness would soon devour his country, and Tibetan Buddhism’s survival rested on a few youth such as Trungpa. “You are like a flower in bud which must be properly looked after,” Jamgon Kontrul told him. Chogyam Trungpa was looked after: A thousand years of Tibetan learning were compressed into his education, like treasure secreted away before the enemy’s arrival.

In young Chogyam’s boyhood what was solidly there one moment might utterly vanish the next. When he was recognized as the Eleventh Trungpa, he acquired a new name and a new identity. His parents and home disappeared when he was taken to be raised in a monastery. Trungpa later wrote a prose poem “Nameless Child to describe this childhood with all the usual elements of childhood missing:

Because he has no father, the child has no family line. He has never tasted milk because he has no mother. He has no one to play with because he has no brother or sister. . . . Since there is no point of reference, he has never found a self.

If that describes Trungpa’s missing childhood, the larger world around him, indeed everything familiar and comfortable, would soon become a missing item as well. The elements that usually make up one s sense of self—such as country, class, culture, a shared first language— were whisked out from under him as the Chinese began their conquest of Tibet.

Chogyam Trungpa supplied one of the first accounts, Born in Tibet (1966), of the peaceful kingdom crushed under the invaders’ boot. Its early pages depicting his unusual education yield to tales of his hiding in the mountains after the Chinese occupied Tibet and then of his dramatic attempt to escape. He meandered the trackless Himalayas over one icy peak after another, month after month, uncertain of his direction, as his food ran scarce. It can seem almost miraculous, given the near-suicidal odds, that so many lofty eminences of Tibetan Buddhism (the Dalai Lama, the Sixteenth Karmapa, Dilgo Khyentse, Dudjom Rinpoche, etc.) survived the harrowing trek into exile, to give their religion a second chance abroad. Among those ragged majesties was Chogyam Trungpa, stumbling into India more dead than alive in late 1959.

The Chinese invasion of Tibet did not merely destroy Trungpa’s past; it also destroyed his future. Everything he was trained to do was erased from the blackboard. The Dalai Lama appointed him spiritual director of the Young Lamas School in Dalhousie, and he held that extremely modest position until 1963, when he received a scholarship to Oxford. There Trungpa became a Guiness Book of Records unto himself. He was the first Tibetan to become an English citizen, the first Tibetan to compose a book directly in English, the first to start a Tibetan Meditation Center in the British Isles, and a few years later the first to start one in America. All those firsts indicate that the old rules no longer applied and even he could not say in advance what the new ones would be.

Lama Yeshe continued to keep his monastic vows, as though he had never left Tibet. Chogyam Trungpa, however, entered into a no-holds- barred encounter with the West. As a child he had desired to learn foreign languages (and had to settle for learning Tibetan dialects like Amdo). Now in England his quick mastery of the language was an astonishment. Allen Ginsberg later praised Trungpa’s ability to talk every sort of spoken English from redneck, hippie, chamber of commerce, good citizen [to] Oxfordian aesthete slang. At Oxford Trungpa mastered more than the English language, however. If degrees were given in the “good life,” Western version, Trungpa would have earned his Ph.D, overnight. During his escape from Tibet, when no water had been available Trungpa went thirsty rather than drink Tibetan beer (chang) or fermented spirits. In the West he may never have refused a drink again. He was rarely out of control, but his sports car certainly was that evening in 1968 when he crashed it into a joke shop, full of comic novelties. The consequences were hardly humorous, though, having left him paralyzed on his left side for life.

Trungpa drew from his auto accident a valuable lesson, though not exactly the most obvious one. He decided to return his lama s robes, wishing no longer to hide behind a monk’s appearance or anything that put him at a different angle of experience from those around him. He surrendered his monastic vows but not, he declared, the intention behind them: “More then ever I felt myself given over to serving the cause of Buddhism.” He promptly celebrated this dismantling of barriers— between lama and layman, between Tibetan and Westerner by marrying a sixteen-year-old upper-class English girl named Diana Pybus. His Tibetan colleagues were outraged that Trungpa had betrayed not only his religion but also his country at the hour of her greatest need. Trungpa believed, to the contrary, that those colleagues were engaged in a more subtle betrayal, clinging to outward Tibetan forms (but not necessarily to the inner Buddhist essence) in circumstances where they no longer applied. Samye Ling, the Tibetan center he cofounded in Scotland, should be, he argued, simply a meditation center. However, Trungpa was outnumbered and abandoned; he had lost his country, and now he forfeited the regard of his fellow Tibetan exiles. In those dark days of 1969 he decided—to the relief of all concerned—to move to America. One of his colleagues predicted, “If anything, his outrageous behavior, his affront to conventions, may make him more charming to the Americans.

The prophecy proved more accurate than anyone could have guessed.

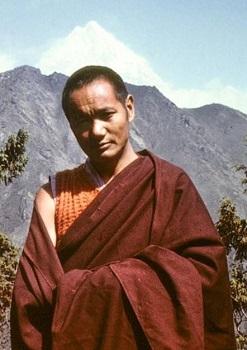

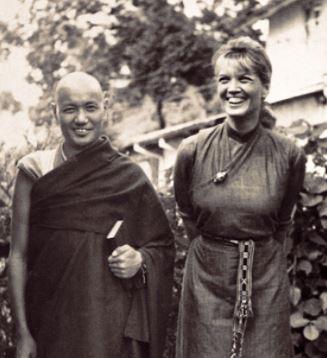

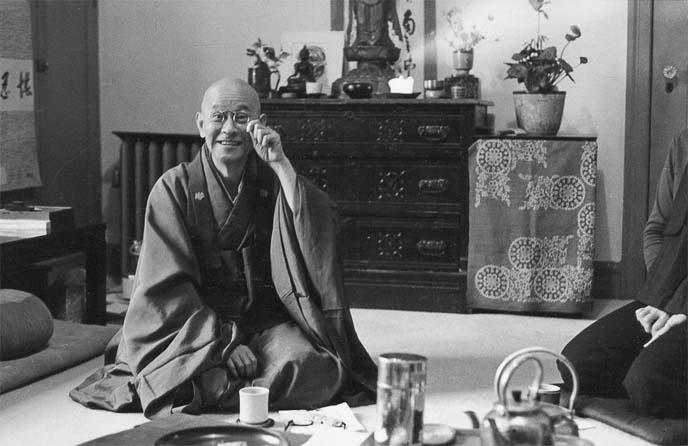

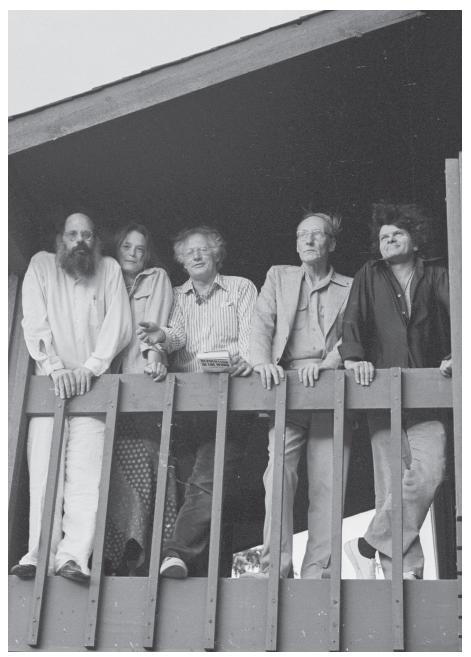

Chogyam Trungpa – Tail of the Tiger, 1971

JANUARY 1 970 — THE START of a new decade. For Chogyam Trungpa it marked his entrance into yet another new world. In leaving England, he left behind much that he valued. From their experience of empire in Asia, Englishmen of the better sort knew the protocols of respect due a gentleman from the East. Like Britain, Tibet possessed a historical civilization with its pomp and ceremonies, and Trungpa relished the formalities and the courtesies of English public life. (In America he would instruct his students how to speak proper Oxonian.) But if Englishmen understood how to treat Orientals, they also knew how to pigeonhole them. Numerous English persons expressed an interest in Trungpa but only as a fascinating curiosity—in the spirit of “Let’s go see the exotic lama at Oxford!” Few, very few, indeed, thought he might have something worthwhile to teach them.

Americans by contrast acted as though Trungpa had the alchemist’s stone or the formula for eternal youth tucked away somewhere in his baggage. During the early 1970s in America the mystical East was more in fashion than fashion was. Trungpa disappointed some spiritual seekers because he hardly looked (or acted) the part of a guru. He wore business suits, he eschewed health foods in favor of steaks, and he smoked and drank. That he was such a modernized, Americanized guru worked overall in his favor, though. In no time, it seemed, crowds attended his every movement and young people hung on his every word, willing to change their lives according to what those words were.

In an ancient fable, wherever the Buddha stepped lotus flowers grew. Wherever Trungpa set foot in America, Buddhist centers sprang up. In 1970 some of his students from Scotland purchased land in Vermont to establish Tail of the Tiger, the first Tibetan center in the United States. That summer Trungpa taught at the University of Colorado, and two centers began in Boulder. Swiftly there followed centers in Los Angeles, Boston, San Francisco, New York, and Toronto, as well as meditation lodges, a fledgling college named Naropa, an experimental therapeutic community m Connecticut, preschools, even a theatrical group. By 1973 a nationwide organization, Varjradhatu, was set up to oversee all these organizations and activities, which behind their diversity reflected a single fact: Chogyam Trungpa had learned the secret of teaching Americans.

Before 1970 the only form of Buddhism with any general appeal here was Zen, and especially popular was the roshi or master, Shunryu Suzuki (1905-71), who founded the Zen Center in San Francisco. His talks, published under the title Zen Mind, Beginners Mind (1970), sold more than a million copies.Trungpa and Suzuki were bound to detest each other. In addi tion to the enormous difference between flowery Tibetan and spartan Zen Buddhism, a generational difference separated the two men. Furthermore, Suzuki kept the traditional vows and precepts, while Trungpa broke them all. When they met in 1970, however, the rapport was instant and profound. Soon the younger man was calling Suzuki Father, and the older man calling Trungpa his “son.” They shared the experience of both being cut adrift from their Asian homelands and cast into America—and liking it.

Suzuki originally came to this country to provide middle-class Japanese-Americans some instruction, but he stayed on and started teaching ordinary Americans, because (he said) Buddhism needed some fresh opportunity, some place where people’s minds weren t made up about Buddhism.” That Americans were ignorant of Buddhist histories and hierarchies might well work out to be an advantage. It could have been Trungpa talking: For both of them the United States was Buddhism s brave new world.

When Suzuki invited Trungpa to lecture at San Francisco s Zen Center, he cautioned his students, “Someone is coming tonight. After he comes, maybe no one will be left here at the Zen Center but me. Trungpa arrived, having to be carried in on a stretcher, as he called out to Suzuki, “I am so druuuunk!” Yet that night, David Chadwick recalled in Crooked Cucumber, Trungpa “delivered a crystal-clear talk, which some felt had a quality of not only being about the dharma but being itself the dharma. Suzuki joked to the students that, if this was drunkenness, they should drink more. (Suzuki never criticized Trungpa’s excesses, but worried only that he would not live a very long life.)

What did Trungpa learn from Suzuki? Trungpa’s mind housed the equivalent of a library about Tibetan Buddhism to pass on to his students, but there was Suzuki teaching mainly one thing: meditation. Where there is practice [i.e., meditation], Suzuki said, there is enlightenment. How simple! Trungpa thought. But in Tibetan Buddhism meditation is a somewhat advanced practice, begun after one has mastered considerable instruction and discipline first. With Suztrki’s example before him, Trungpa had his American students bypass the potentially bewildering preliminary studies and dive straight into meditation immediately. Trungpa treated all the young men and women coming to him as though each was already capable of emulating the great masters of Tibet. Every hippie who came to Trungpa, simply by coming to him, took on some aspect of a noble monk. Most of them relished the elevation, even if they were not sure exacdy what was happening.

Trungpa did suffuse his students with his high estimation of their potentiality, but unlike Lama Yeshe, he did not invariably treat them tenderly or sweetly. In Cutting through Spiritual Materialism (1973) Trungpa said it was a guru’s duty to insult his students (meaning, affront their distorted egotism), and in this duty he did not fail. Some inner radar of his seemed to detect where a person’s hidden vanity lay, and he would home straight in on that sensitive spot. Consider the time when the American called Bhagavan Das—made famous in Ram Dass’s best-selling Be Here Now, where Das is portrayed wearing blond dreadlocks and walking barefoot all over India—came to pay Trungpa a visit. That night everyone drank until they passed out, and the next morning Das woke to find his long blond dreadlocks had been cut off while he slept by Trungpa. The night before Bhagavan’Das had preached that material objects do not matter, and Trungpa thus demonstrated that they did matter to Das. Fortunately for Trungpa this was the 19 7 Os, when many people imagined that being confronted would remake them for the better.

Trungpa could have taught the traditional dharma in the traditional way, and in doing so increased his students’ comfort and ease in themselves. But he preferred “to wake them up,” as he called it. His approach could mean dispensing with nicety and politeness, as his encounter with the poet Allen Ginsberg illustrates. The two of them first met in New York City in 1970 quite accidentally, when they scrambled to get into the same taxi. Ginsberg and Trungpa next bumped into each other on the other side of the continent, in a bar in Berkeley, California.

Sitting at the bar, Ginsberg complained to Trungpa how endless touring, endless planes to catch, endless lectures to give had left him exhausted. Trungpa volunteered a different interpretation: “You’re exhausted,” he told Ginsberg, “because you don’t like your poetry.” Talk about hitting a person where it hurts. “What do you know about poetry?” Ginsberg shot back at that—that obnoxious Mr. Know-it-all. Taking another sip of his Bloody Mary, Trungpa continued as though Ginsberg had not spoken: “Why do you need to depend on a piece of paper when you recite your poetry? Don’t you trust your own mind? Why don’t you do like the great poets, like Milarepa—improvise spontaneously on the spot?”

The Bloody Marys were evidendy fueling Trungpa’s criticism, which now switched to Ginsberg’s appearance. “Why do you wear a beard? he asked him “You’re attached to your beard, aren’t you? I want to see your face.” Ginsberg excused himself. He darted into a nearby pharmacy, purchased some scissors, and snip, snip, off came half of his beard. Pleased with his spontaneity, Ginsberg returned to the bar, where Trungpa looked up from his drink and noted perfunctorily, “You didn’t shave it off. All you did was cut off two inches.” Trungpa was already late for a lecture he was to deliver, but he proposed having a few more drinks while Ginsberg shaved the damned thing off. Ginsberg found himself in the unusual position of being the socially responsible person: If Trungpa would go give the lecture now, he would shave during the lecture.

Midway through the talk a clean-shaven Allen Ginsberg emerged from the men’s room, and Trungpa shouted from the stage, “He took off his mask!” That evening Ginsberg mounted that stage and recited poetry— not the old-fashioned poetry you find in books—-but poetry he made up on the spot, full of awful rhymes like “moon” and “June” and “dear” and “beer.” “It was the first time I ever got onstage without a text and had to improvise,” Ginsberg recalled. “And it was really awkward and unfinished, but it was … so liberating when I realized I didn’t have to worry if I lost a poem anymore, because I was the poet, I could just make it up.” He also discovered that he liked sporting about sons beard. With the beard, he was a recognized, labeled media personality; without it he could be anybody, or nobody, whoever he pleased. Upon reflection, Ginsberg was thunderstruck that a mere couple of hours’ contact with Trungpa had altered radically both the way he looked and the way he wrote. Then and there Ginsberg decided to ask Trungpa to be his teacher and, please, insult him some more.

Whenever he encountered Trungpa, Ginsberg thought, how fresh and unexpected he (Ginsberg) became, even to himself. Is that what having a guru was like—to be in a state of continuous productive upheaval? Ginsberg called the quickened sense of being he felt around Trungpa (this was the early ’70s, after all) “love”: “The reason I wound up with Trungpa was because I loved him.” In 1970 and 1971 many others were also falling in love—or fascination, or hope—with this recent arrival to America.

WHAT TUNE WAS TRUNGPA playing on his enchanted flute that so beguiled his audiences in the 1970s? Unlike other Tibetan lamas in exile, who tossed off the customary pearls ofTibetan Buddhism before western students, Trungpa realized that what a teacher might teach today was a real problem. All the beautiful religious truths of all the sacred traditions had already been repeated over and over ad museum.

Yet Tibetan Buddhism did possess certain insights, about the nature of human existence, about the relation of life to death, which were hardly common currency in America. The difficulty, the great doubt, was whether they could ever be rendered to a contemporary audience in the West.Trungpa had suddenly to speak in a language invented by daily journalists, Dale Carnegie, and Hollywood scriptwriters. Could he render Tibetan mysticism not only into novel English but into secular sentiments? That would be something new in the world. He intended to try: Trungpa introduced his key work Shambhala (1984), with the words “This book is a manual for people who have lost the principles of sacredness.”

Item number one in that “manual” wasTrungpa’s insistence that the principle of sacredness may be, actually, quite a good principle to lose.

Back in the ’70s, almost everyone attending Trungpa’s talks had already toured the spiritual bazaar, donned and discarded one self-help and quasireligious fad after another. Trungpa opposed this quest for salvation; he criticized Americans for using “spiritual techniques” to become even more egotistically preocuppied with themselves. Saying mantras or wearing robes or even religion itself, he added, was not going to save you. Which raises the question What then will?

In Henry James’s The Ambassadors the character Strethers repeatedly tells himself, “Only let go,” and in various ways “only let go” was what Trungpa told his students. Only let go of your search for salvation, and you may discover that letting go was what you were searching for. When Trungpa climbed onstage with his nymphs and Scotch, he cut through his audience’s preconceived ideas of spirituality; he quite literally cut through Bhagavan Das’s, when he cut off his dreadlocks. Once when Trungpa lectured in Vermont, Ram Dass (or Richard Alpert—not to be confused with Bhagavan Das) came and sat on the stage below him, as though indicating that he was just beneath Trungpa in spiritual attainment. Trungpa said nothing but throughout the lecture dropped the ashes from his cigarette into Ram Dass’s hair. At another retreat Trungpa’s senior students, at his prompting, rushed into a serious discussion with peashooters and turned the room into a hullabaloo of pillow forts and play fights. Is that the way serious-minded Buddhists behave? Perhaps. For nobody in the room wgis now daydreaming or bored or lost in intellectual argument any longer, but all were, well, cutting through spiritual materialism.

Item number two in Trungpa’s manual concerns what happens when you stop striving after the way you think things should be. If you surrender your sense of limitations and your need to redeem them, you may find yourself, he suggested, already living in an uncontrived, happier condition. Needless to say, a good American therapist would not agree. Freudian psychology holds that beneath the layers of cultural accretion is still a stratum of troubled personal identity, composed of identifiable complexes and leftover childhood neuroses. In Tibetan Buddhism, however, pare down a personality far enough and you reach, beyond childhood s wrong beginnings, into pure luminous being, no different from what the Buddha experienced upon enlightenment. Trungpa could hardly tell his initial American audiences that they were all secretly Buddhas, for they would either dismiss him as a mystic or their egos would inflate like balloons. Trungpa’s challenge was to smuggle in this “prepsychological, religious way of looking at things under the cover of ordinary American talk.

He thus talked about buddha-nature without appearing to, by alluding instead to a person’s basic goodness. In Trungpa-speak, “basic goodness does not mean, despite its sound, niceness and decency. One disciple recalls telling Trungpa that she was basically a nice person, and he winced, as though he had just bitten into something truly nasty. He wasn’t interested in niceness.” Nor was he a psychotherapist who would either support or correct people’s vested notions of themselves. When his students expressed their convictions with great earnestness, he would some- times look out the window and yawn.

Trungpa thus attempted his end run around psychotherapy. Psychiatry and psychoanalysis, he knew, can be powerful tools for dealing with personal problems, but sometimes one cannot even know what the problem is. By contrast, awakening one’s basic goodness (a/k/a buddha- nature) may make some problems dissipate or recede to inconsequence without any analysis at all. You may be already all right, if only you will allow yourself to be. His task was to jolt people into realizing this latent potency, this healing (or actually already healed) aspect within themselves. Cheer up, Trungpa would exhort audiences at his talks. “Cheer up right now!”

Item number three in Trungpa’s manual is for those who have cheered up. If your own moody self-obstacles don’t get in the way, you won’t need religious principles, for then everything will appear sacred. Once you experience your own basic goodness then everything, and not just what you previously liked, may begin to seem good; whatever you encounter may now interest you. In Chogyam Trungpa: Sa vie et son oeuvre (2002) the French writer Fabrice Midal catalogued Trungpa’s own interests, and their range is staggering. His enthusiasm for the arts might be expected, since they appeal to the same imaginative faculty that religion does. But in addition to art, Trungpa considered that daily life, cooking, speaking, the way you drank your tea, the way you shopped for clothes, all can be—for the person who has “cheered up”—an excellent way to practice Buddhism. A few critics objected that the arts, as Trungpa envisioned them, did hot really produce art. The goal of the “spontaneous poetry” that he encouraged Ginsberg to write was not great poetry but an intenser awareness in the poet (or poet-manque). The “arts” Trungpa himself practiced—spontaneous poetry, calligraphy, ikebana flower arrangement, the zen of archery, etc.—were like the cooking and elocution he taught, activities that demand single-minded concentration and avoid complexities of thought. That greater art made from irony, contradiction, and thought doubling back on itself—Shakespeare’s plays, James’s novels, Yeats’s poetry, Cezanne’s painting—lies outside Trungpa’s canon. But such art may come at too high a price, he thought, since complex reasoning and second thoughts so often trap people within their own psyches and cut them off from their spontaneous goodness.

The challenge was How could Trungpa coax people into realizing their elusive “basic goodness”? Trungpa was no longer a monk, and he dismissed religion, yet he did what Tibetan lamas have always done: He encouraged his students to meditate. (Meditation is so empty of content that it’s hard to turn it into spiritual materialism or appropriate it for egotistical purposes.) Meditation completes Trungpa’s “manual for people who have lost the principles of sacredness,” which, if the truth be told, was a manual for reintroducing those principles, albeit incognito or in disguise. Trungpa’s principle of “letting go” resembles sunnyata (or emptiness); his “basic goodness” is the Buddhist principle of compassion; and appreciating or accepting whatever happen? begins the Tibetan practice of nonduality. Thus through a roundabout back entrance Trungpa led his students into something rather like Tibetan Buddhism, without the name.

Harvey Cox, the Harvard theologian and author of the bestseller The Secular City (1965), took to the road in the early 1970s in search of “an authentic contemporary form of spirituality.” All such roads then led to Trungpa’s Naropa Institute in Colorado. (In the early 1970s, Naropa metamorphosed from a mere idea—that of combining meditation with academic study into a college almost overnight, thanks toTrungpa’s ability to combine the visionary and fund-raising. Today, Naropa is the only fully accredited Buddhist university in the United States.) Cox went to Boulder to scoff, but he stayed to sit. Skeptical about the fad of meditation and half intending to expose it, Cox experimented with meditation himself. He was astonished:

From the very outset, from the first hour-long meditation, I sensed that something unusual was happening to me. My level of internal chatter went down. I .did not invest situations with so many false hopes and fantasies. I walked away from the sitting feeling unruffled and clear-headed. I could teach with more precision and listen to people more attentively, [etc.]

Besides meditation, what Trungpa taught was himself or through himself, Cox surmised, so you almost had to be there. Some teachers write so well, you need never encounter them personally, while others depend upon eye contact, a gesture, or a knowing look to give their message substance. Trungpa was neither of these types of teacher—neither a book, nor an exemplar—Cox believed, but one whose value emerged fully only in the teacher-student or master-apprentice relationship. In that relationship Trungpa could be offensive, or be tenderly kind, as he keyed himself to the needs (if not the wishes) of the particular student. Being with him, his students said, could feel so ordinary—rather like being in the weather—but an uncanny sense of something more kept stealing in, when one wasn’t looking.

He seemed less a saint than a provocateur, whose genius was to make every encounter exciting, fun. If it doesn t have a sense of humor, Trungpa would say, “it’s not Buddhism.” His own humor could sink to childish levels: He might stand behind a door and when someone entered jump out and yell Boo! Once after his lecture, a woman announced she was a vegetarian and demanded to know how Tibetan lamas could eat murdered meat. Instead of pointing out that Tibet did not grow enough edible crops, Trungpa paused, and finally said in a tiny voice, “Well, you are what you eat.” The audience burst out laughing, though no one knew for sure what he meant. It was typical of Trungpa not to solve people’s puzzles but to return them to them, which oddly kept them returning to him. The introduction of Tibetan Buddhism into America became, in his hands, not a matter of soul-anguish or dour proselytizing but playful as a theater piece.

THE YEAR 1974 SAW Trungpa change his manner of teaching. That year His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa first visited the United States. It was the Karmapa who, some thirty-odd years before, had had the vision that led to the infant Trungpa’s recognition. In Tibet the Karmapa was treated as a king of kings and considered little short of divine, afterwards, in exile, he lived like a poor peasant at first, and he enjoyed that equally, joking with Indians in the bazaar. In hosting his visit, Trungpa might heal the rupture that had estranged him from the Tibetan community ever since his marriage. The Karmapa s visit thus represented the homecoming to the Tibet that Trungpa could never go home to in person.

Trungpa announced to his students that His Holiness the Karmapa would honor them with a visit in Boulder. Their response was: Groovy. “Let’s show him a great time,” one student suggested. We can take him out for steak and then to a disco.”

Second student: “He can sleep on the water bed.”

Third student: “Do we have to vacuum the floor?”

Boulder back in the ’ 7 Os was a groovy little city. Car bumper stickers proclaimed, “Visualize Using Your Turn Signal,” and Boulderites voted marijuana their favorite cure for a hangover. Trungpa suffered a revulsion: Such casualness was not the proper response to a prospective visit from His Holiness. Imagine a Catholic, ecstatic about the Pope’s imminent visit, who suddenly hears someone next to him say, “As long as we don’t have to clean the toilet.” Trungpa felt a similar disgust at his students’ reaction to the arrival of the holy of holies.

Trungpa’s first American students were in the main hippies, and secretly he didn’t much care for hippies (whereas a “Tibetan hippie” is what Lama Yeshe sometimes called himself). A poster of that era showed a longhaired youth meditating naked in the woods, and its caption read, “Milarepa Lives!” Trungpa considered the poster near-blasphemy. Milarepa was Tibet’s great ascetic yogi (circa 1025—1 135), but his asceticism entailed more than shedding his underwear and gazing vacant-eyed at his navel. Milarepa belonged to a venerated and formal tradition of learning. It was time, Trungpa decided, for these students to learn veneration and formality. For the Karmapa’s visit they borrowed good china and silver and polished that silver to its brightest sheen. Many of the young men bought their first suits, and the young women learned that the height of fashion was not the tie-dyed dress.

Theirs would be no brief flirtation with respectability. Prior to the Karmapa’s visit, Trungpa would go to give his talks wearing whatever he happened to be wearing, perhaps khaki pants and a plaid shirt, and following his talk he might stop at Arbie’s to grab a quick bite. Subsequent to the Karmapa’s visit, be began wearing suits at his talks, and he expected his audience to dress respectably too, to honor what was being taught. Those audiences were hippies fleeing their own traditions, but it was time they acknowledged they had landed, in fact, in another tradition. Trungpa took the declining hippie patient into his clinic and sent him forth a robust bourgeois. One student of his reminisced about the “makeover”:

Everybody [in the early ’70s] was ready to do anything. Anything!

We got into this, and it seemed fantastically radical and profound.

Fifteen or twenty years later, we all look like Presbyterians. . . .

There’s a kind of normalcy, which is very much the direction

Trungpa Rinpoche pushed us in.

The videotapes of his early talks show a wild-eyed audience, minimally clothed and maximally hirsute; the late ’70s ones, sedate folks who might have ambled over from a Rotary Club or PTA meeting. Trungpa repeatedly addressed his audience as “ladies and gentlemen,” which may sound quaint, but he was reminding these refugees from respectability that they had become the “ladies and gentlemen” of a great tradition. Trungpa did for the counterculture what Bill Clinton later did for the Democratic Party: he escorted it from the excitable, idealistic margins and relocated it in the supposedly durable center, which had hitherto been deemed too conservative for habitation.

Trungpa had at first lived informally with his students, but he now set up a kind of court around himself. How do you, in fact, organize a large group, so that many people can relate to a central figure? At first he copied the predominant model on offer in America—the corporate organization—with its divisions and departments and hierarchy of officers, but he came to dislike that model as too impersonal, too mechanical. He hit upon an inspiration, albeit almost a millennium out of date: A medieval court would be nobler, a reminder to his students of their heroic capabilities. Other American Buddhists poked fun at Trungpa’s pretensions, but Trungpa liked fun. Sometimes when he traveled in America and Canada, he went incognito—as the Prince of Bhutan. Doubtless a joke, since few Americans would know where on earth Bhutan was, if it was. But as Freud said, our jokes unconsciously reveal ourselves … in this case, revealed that Trungpa was redonning the ceremonial regalia of the spiritual prince he’d once been in Tibet. The students traveling with him grew a trifle weary every evening of having to dress up in tails and long dresses and white gloves, in a charade of royalty. Tie-dyed dresses and tattered jeans had come a long way.

Harvey Cox, returning to Naropa after the Karmapa’s visit, remarked on the new regime there. He was greeted upon his arrival with polite courtesy: “How long can you stay with us this summer?” Previously there had been no you/us, Buddhist/non-Buddhist distinction. As a Christian,’ Cox was relieved that Trungpa was now emphasizing his Buddhism ecause, before, it had so blurred into generic spirituality that how could one know he was not a Buddhist.

After the Karmapa’s visit, Trungpa started instructing his students in the ngondro, the hundred thousand prostrations, mantra recitations, visualizations, mandala offerings, etc. Up and down, up and down, they performed the prostrations, fearing that their knee joints might calcify and their muscles petrify. But the longer they persevered, the more supple t eir bodies became and some claimed even their acrid sweat doing these exercises turned sweet tasting. Such advanced techniques should be imparted, he believed, only in the close supervision of the teacher-student relationship. His talks (and the books made from them) therefore remained general for a general audience. Whoever wished to delve deeper and do the hard work, could come study with him, and thousands did’ Trungpa thus created two “tracks” of Buddhism in America-one public and quasi-secular, the other private and religious—and by the early 1980s both appeared to be alive and thriving.

OR SO IT APPEARED. Skeptical outsiders began to express reservations. Could this be the same Chogyam Trungpa about whom the evotee relates an inspirational success story and the hostile critic reports misconduct leading up to tragedy? .

Both sides agree that Trungpa hardly comported himself according to The Lives of the Saints. There was the little matter of, well, sex. An Oriental pasha might have envied Trungpa as he selected the female devotee who would enjoy his favors that evening. In certain periods the Boulder center

had a sign-up list, to which women added their names who wanted to sleep with him, and Trungpa would scroll down the list, so that each night a new beauty materialized in his bed. There was nothing sly about it: Trungpa believed that sex, defanged of possessiveness, was as natural as in the Garden of Eden. He never assumed that a cloistered, desexualized atmosphere was the best context for spreading the dharma—or even if it was, it was hardly the atmosphere prevailing in 1970s America. The inspiring’ teacher Trungpa thus gained a second reputation: Give a free-association test to an American Buddhist, and the first association upon hearing Trungpa’s name may not be dharma or enlightenment but fucking.

And the second word association might be booze. Erotic activity, even for the enthusiast, uses up only a few hours on most days, but Trungpa appeared able to drink all the time. Eventually the beer bloated his body and had to go; the whiskey corroded his innards and had to go; and so he settled upon the gentle Japanese liquor, saki. Ginsberg had seen hooch lay waste to Jack Kerouac, and he attempted to rescue Trungpa from the same fate.Trungpa remained unfazed, saying that Ginsberg’s confusing him and Kerouac was more muddled than any drunkenness. In an essay “Alcohol As Medicine or Poison,” Trungpa proposed there is a right and wrong way to drink; “Conscious drinking—remaining aware of one’s state of mind— transmutes the effect of alcohol.” To his young admirers their teacher, fueled by such mindful drinking, winged into the furthest reaches of mind and thought, where man had scarcely trod before. Others disagreed. When the poet Robert Bly was giving a reading in Boulder, an inebriated Trungpa stumbled onstage and started banging a gong. Bly could barely contain his fury, demanding; “Your drunken behavior—is it just you, or is this a traditional manner, or what?” Trungpa answered, “I come from a long line of eccentric Buddhists.” As his students emulated him—perhaps they were drinking in the wrong way—Trungpa’s Boulder center became the only Buddhist sangha in the world to have its own chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Trungpa saw little benefit in being bound by ordinary constraints.

“I’ll do anything to wake people up,” he repeatedly said. In fact, he expanded the Catalog of Anything. One of his attendants daydreamed continuously, so Trungpa willfully tripped going down the stairs to startle him into being more alert. The attendant apologized profusely, but soon his daydreaming resumed. The next time Trungpa threw himself past his dozy attendant down the stairs he wound up in the hospital. Another time Trungpa had his driver drive his Mercedes into the water on the beach, from which sea burial it had to be laboriously extracted. Some marveled: See the complete freedom of the guru! Others countered, What do you expect of an uninhibited five-year-old? (Still others like Allen Ginsberg thought an adult five-year-old the best guru imaginable.) Trungpa was certainly an enfant terrible, or genius, at shocking people out of their complacency. Perhaps he was successful nineteen times out of twenty at rousing his students from their comfortable self-deceptions. “Guru” may be the one profession, however, where a 95 percent success rate equals failure.

Ginsberg enjoyed having his status quo turned upside down. But others like the poet W S. Merwin wanted to learn about Buddhism, without stepping onto a roller coaster zooming off the rails. In 1975 Merwin and his Hawaiian girlfriend, Dana Naone, applied, late, to participate in Trungpa’s three-month retreat in Snowmass, Colorado. Merwin had done none of the preliminary courses, however, and he was unfamiliar with Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom” manner of teaching. Three out of four applicants for the seminary in Snowmass were refused, but a famous writer in attendance added luster, and so Trungpa accepted Merwin’s late application regardless.

That Snowmass retreat coincided with Halloween, and Trungpa, as the master mixer of the sacred and the profane, decided a Halloween party might be just the ticket. Instead of donning masquerades, the guests would have their normal egotistical masks stripped off (and, Trungpa intimated, the stripping might not stop there). As the revels accelerated, Trungpa realized that Merwin and Naone were missing from the spirit-bacchanalia. When they refused to be coaxed from their room, Trungpa ordered his guards to break down their door. Merwin, a pacifist, panicked and greeted the intruders waving a broken bottle. After they were forced downstairs, Trungpa yelled at Naone, “You might be playing slave to this white man, but you and I know where it’s at. We’re both Oriental.” Then he demanded, “Are you afraid to show your pubic hair?” At Trungpa’s command, Merwin and Naone were forceably undressed, as Naone screamed at Trungpa “Fascist,” “Bastard,” “Hitler,” and (if those weren’t damning enough) “Cop.” They were then allowed to slouch back to their room, while a seemingly drunk Trungpa ordered everybody else to undress.

As orgies go, the one in Snowmass hardly compares with the Sodom and Gomorrah of a Saturday-night frat party. Surprisingly, Merwin and Naone decided to remain for the duration of the retreat, reasoning that, despite his excess, they could learn from Trungpa things then not taught anywhere else in America. But the gossip mills were churning, and rumors of the debauchery filtered into various poetry circles, where denunciations of Trungpa became the order of the day. Ginsberg judged this righteous indignation pure hypocrisy: “[William] Burroughs commits murder, Gregory Corso borrows money from everybody and shoots up drugs for twenty years but he’s ‘divine Gregory’ but poor old Trungpa, who’s been suffering since he was two years old to teach the dharma, isn’t allowed to wave his frankfurter!”

The brouhaha appeared to be dying out, when Harper’s magazine ran an article, “Spiritual Obedience,” which gave the incident national coverage. The writer of the piece, Peter Marin, professed horror not at the shenanigans but that later neither Trungpa nor his disciples would admit to his having done anything wrong. Some students, so Marin reported, converted the debacle into a teaching or morality play in which the unclad Merwin and Naone were the naked Adam and Eve (and by inference Trungpa must be God expelling them from Eden). Then in November 1978, the Reverend Jim Jones led the infamous mass suicide of his

People s Temple group in Guyana, and some critics barely familiar with Trungpa worried that in Boulder, at Naropa, another Jonestown cult was in the making. Boulder s local newspaper, the Daily Camera, editorialized about Trungpa s guards, his limousines, and his drinking, “To avoid being called a cult, it might help not to act like one.” One man’s guru is another man s fascist, which is what poets like Bly and Kenneth Rexroth now took to calling Trungpa. Rexroth pronounced, “Chogyam Trungpa has unquestionably done more harm to Buddhism in the United States than any man living.”

A de-facto harem at one’s beck and call, a bar pouring drinks nonstop, and a following to humor one’s every whim may seem a formula for any man s downfall. But Trungpa didn’t fall down, not then anyway. Tibetan Buddhism views reality as a kind of magic show, and perhaps Trungpa was a magician, with a sleight of hand making vanish the consequences of his excesses. He was so inspiring a teacher that his students lived in the inspiration; so fascinating that criticism gave way to wonder. In the early ’80s he surprised his followers by announcing that they needed to relocate their headquarters, and after scouring and rejecting half the globe (Bermuda, New Zealand, etc.), he astounded them further by choosing a geographical “nowhere”—Nova Scotia. Shortly after moving to Nova Scotia himself in late 1986, he performed the ultimate magic trick, the final vanishing act.

At the time of his death he was only forty-seven, a body worn out by alcohol: Yet he had accomplished more than most people would, given ten lifetimes. He had been a controversial figure, but the thousands attending his funeral attested to his larger triumph. The day of his funeral was dreary and rainy, and many mourners were frazzled from having driven overnight to get there in time. But as Dilgo Khyentse stepped out of his car, the sky suddenly cleared, the bluest blue, and a rainbow encircled the sun; then two distinct clouds materialized in the sky, and there arched between them another rainbow a ciel et lumicre show such as supposedly light the way as great lamas enter the bardo. Trungpa’s bones were pulverized and mixed with jewel dust, then siphoned into gold statues, to grace more than one hundred centers affiliated with him. Construction began on a mammoth stupa in his honor, which $2.7 million dollars and fourteen years later was completed, with the media and thousands of still-devoted followers attending the ten-day consecration ceremony to pay tribute to his memory. Yes, a triumph . . . had it only ended there.

JUST AS DEATH DID not quite end LamaYeshe’s story it is not the last word in Trungpa’s either. A decade before he died, in 1976, Trungpa had anointed a “dharma heir” to succeed him—one Osel Tendzin, ne Thomas Rich—a former street kid from New Jersey whom Trungpa found amusing. Trungpa put a high premium on being amused. More important, by appointing a Westerner as his dharma heir, Trungpa demonstrated that Tibetan Buddhism could become as American as apple pie—or as street kids from Jersey.

As Trungpa’s successor Thomas Rich would become the head of a whole ancient Tibetan lineage. As befitted such a dharma prince, he was indulged and cosseted, surrounded by attendants and chauffeuied about in limousines. In advanced Tibetan practices a person visualizes himself as having the unlimited potentiality of a deity, which without the proper training can result in a psychological inflation. Possessed of the position and prerogatives of a demigod on earth, Rich grew puffed up. When a venerated old lama visited Naropa, he wanted to give Trungpa’s designated successor a special teaching. Rich/Tendzin hastened to the rendezvous excited, expecting to learn occult powers, masteries that would put nothing beyond him. The old lama’s teachings were disappointingly simple, though, consisting only of: “You must always be kind.

Possibly Tendzin should have scrutinized that lesson more closely. A year after Trungpa died, a shock jolted the Buddhist communities in America. Not only did Osel Tendzin have AIDS, but he had infected several partners without telling them. Tendzin called a meeting to confront the growing scandal, but since he billed the meeting as a teaching, every one had to pay thirty-five dollars to hear his explanation. Trungpa had reassured him, soTendzin claimed, that as long as he (Tendzin) performed the Buddhist purification practices he would not infect his partners with AIDS. Everyone in that audience sat there stunned, scarcely knowing what to believe.

In The Double Minor (1994) Stephen Butterfield, a former student of Trungpa s, said he was not so sure that Trungpa would have been incapable of giving the advice Tendzin attributed to him, even while knowing full well that it was wrong.” Alexandra David-Neel had reported Tibetan yogis condoning, for the sake of enlightenment, deadly practices, and besides, Butterfield argued, in those last years Trungpa’s brains were pick- led m alcohol. Everyone else concurs, however, that Trungpa would not have advised anyone to disregard natural laws, and that Rich (who died of AIDS in 1990) was lying to save his own skin. In fact, back in 1979 when Trungpa first observed his dharma heir veering arrogandy out of control, he had summoned Rich to his house. Trungpa then picked up an enormous calligraphy brush and hurled it so furiously that black sumi ink splattered everyone there (clothes went to the laundry; walls had to be repainted), as he screamed NO: “From now onward, it’s NO! That is the Big No, as opposed to the regular no. You cannot destroy life You have to respect everybody. . . . You can’t act on your desires alone.” Afterwards, Thomas Rich became a reformed fallen angel … for a while.

Yet Trungpa cannot escape blame entirely. He had, after all, chosen as his heir someone potentially capable of wreaking such harms. As the scandal spread, Trungpa’s critics felt vindicated: What else would you expect of a defrocked lama who turned Buddhism into psychobabble and told American narcissists to think even more about themselves? Even his most devoted followers could no longer think, as they had during his lifetime, that their teacher never made a mistake. For some the Rich/Trungpa scandal uttered the last word about Buddhism’s capacity to adapt to the West, and it was an ugly word.

BUT PROBABLY THERE IS no last word about someone so complex as Chogyam Trungpa. People who met him during the 1970s either (a) became his students or (b) were outraged by him. He was outrageous. He would sometimes meet a woman by immediately placing his hand on her vulva and saying, “Hi!” From this distance, however, a third reaction to him is possible—curiosity: What was it all about? What was he up to?

Pundits labeled the 1980s the “Me Decade,” but the 1970s might be called the “God Decade.” The era was rife with religious dabbling and spiritual experimentation, and what built up Trungpa s reputation during those years caused it to unravel somewhat afterwards. His books were assembled from talks, and the impromptu period-hip rhetoric that made them appealing then now makes them read, on the cold page, dated and disjointed. The same was true of his conduct. Trungpa s drinking and womanizing made him seem in the liberated 1970s one of us. Drinking with him, and then discovering the incredible extent of his discipline and practice,” recalled one student, “convinced me Buddhism was not just for people sitting on mountaintops.” But as the hedonistic openness of the ’70s yielded to the “political correctness” of subsequent decades,Trungpa has come to seem one of them—someone whom you d think twice before entrusting with the education of your soul.

Critics censure Trungpa for his heedless example, especially in matters of sex. Yet regarding his “satyriasis, Trungpa was not a typical Don Juan. Although half crippled, he followed a grueling schedule with no privacy or days off, and women were comfort, his consolation. Sometimes when the perfumed hour of rendezvous arrived, and the lights dimmed, he only asked of his prospective lover, “Please hold me, Sweetheart. Consequently, unlike conventional Don Juans, his promiscuity did not leave in its wake a bitter succession of resentful ex-conquests. A conference of Buddhist women that met in Boulder is revealing in this regard. Some participants, breaking from the official agenda, began tearfully to tell of their sexual exploitation by Zen roshis and other Buddhist teachers. The air in the room grew tense, as everyone waited for someone to denounce Trungpa. Yet none of his former paramours, it turned out, felt ill-used by him. Some women defended Trungpa, saying that his physical intimacy was an extension of his emotional intimacy The others postulated that Trungpa was operating on some honorable but different principle, even if they weren’t sure what that principle was.

That principle, to give it a name, was William Blake’s “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” Trungpa was excessive sexually and in drinking, certainly, but he was excessive in everything: in counseling his students, in the number of talks he gave, in the variety of art projects he instigated, in building up his organization. To have behaved with temperate caution in the erotic sphere would have been, he thought, to give sex more than its due. Excess, in fact, may not be the right word but a negative label applied retroactively to behavior that at the time people thought of as rather positive—as breaking dead prohibitions and extend- ing life into an exciting new fullness. His “outrageousness” was an (almost) acceptable language’ of that era, and by speaking it he reached people even LamaYeshe could not.

Trungpa, in any case, had no desire to be a poster boy for the conventional good. He did not believe Buddhism’s mission was altering things or changing behavior, but rather bringing more awareness to whatever one did. He was not attempting to teach us right and wrong,” his disciple Pema Chodron said, but how “to relax into the insecurity, into groundlessness. He taught me how to live, so I am grateful.” Pema Chodron is an American Buddhist nun who for twenty-five years has abstained from sex and alcohol, yet she defends Trungpa: “As far as I’m concerned, if you re going to call things right and wrong you can never even talk about fulfilling your bodhisattva vows.”

Instead of preaching about right and wrong, Trungpa thus tumbled down the staircase; rather than teach morality, he drove his Mercedes into the wet sand. He handed his companions a wacky dilemma to be present to and to solve. This is the situation, he seemed to imply; give it all your awareness, figure it out. People chase around and around in theii own thoughts, Trungpa said, which gets them nowhere. If for once they can be shocked out of their mental habits, their circus of internal distractions stunned into silence, then they may discover a core of rightness and kindness and happiness that has been there all along. They will then be naturally kind, naturally alert, precise in their dealing with situations, and accurate in their relations with others. Meditation will get you out of distractions and obsessions temporarily, while you do it. Trungpa s outlandishness was meant to jolt people out of distracted states permanently, for which he was labeled, then, and even more since, an untrustworthy and immoral teacher.

But morality was not a big problem, Trungpa thought; he could handle morality. When Boulder’s Protestant ministers objected to a scandalous man like Trungpa teaching youth, he sent Harvey Cox of Harvard to reassure them. After the Halloween scandal, when all its participants sank into an embarrassed silence, Trungpa couldn’t understand why nobody was talking about it. (Discussion might have even made sense of the scandal. Seeing Merwin out of step with the rest, Trungpa could have asked Mm to leave, but decided it was kinder to shock him out of his aloofness.) So long as nothing was deceitful or hidden, he thought, everything would come right in the end. Toward the end of his life Trungpa acknowledged he may have made a fatal mistake in America, but that mistake fell in an area other than morals.

HIS, GREAT FAILURE IN AMERICA, Trungpa came finally to think, was that he had undervalued the importance of psychology. When he first arrived in this country, he listened carefully to young Americans talking among themselves, and he recognized that they used psychological frames of reference. When they described their experiences in subjective, personal terms, Trungpa took it to be a cultural phenomenon, a facj—like the way, say, they decorated their rooms. With his intuitiveness and linguistic mimicry, he adapted to the fad with ease, and he became the panjandrum who translated Tibetan metaphysics into good psychological lingo. He knew, for example, that “living in samsara” was not the same as a neurosis, but if he used psychological terms, his students got it right away. And perhaps only he remained unconvinced by what he said. For Trungpa did not really subscribe to the Freudian psychological understanding of character and personality.

Many Americans at that time insisted that individuals needed to do the psychotherapeutic work on themselves first—work through their personal handicaps left over from family and childhood—and only afterwards would they have the inner clearance to attempt spiritual work. Trungpa thought that progression from psychotherapy to spirituality was pure humbug. Sadness, aloneness, depression he did not consider internal maladies in need of a psychiatrist. They were part of the human experience of being alive, and if you did not treat them as a problem, especially an insurmountable problem, they would cease to be one. The “Cheer up! ” with which he exhorted audiences made it seem easy: You can activate the potentiality for happiness within yourself simply by choosing to, by siding with something beyond mood, deep and true within yourself. As it says in the HevajraTantra:

Sentient beings are just Buddhas,

But they are defiled by adventitious stains.

When stains are removed, they are Buddhas.

Trungpa, it will be recalled, did not really have a childhood but, in effect, a long meditation period instead. And so he minimized the early traumas still causing havoc in seemingly composed adults. By discounting the importance of the individual psyche, Trungpa optimistically assumed that creating a hybrid Western Buddhism would face no large obstacles. He also could be cavalier in choosing his dharma heir: So what ifThomas Rich was scarred by his upbringing, when realizing his basic goodness would heal those scars. Only late in the day did he realize a psychological orientation belonged to America as much as does technology or vast geographical distances or mixed immigrant populations, and to plant the dharma in America required planting it in personal neuroses and postadolescent hangups. In any American contest between a person’s psychological history and his innate goodness, Trungpa finally saw, the odds were that personal history will win out. After ten years teaching in America, he told a friend that Freud was more relevant than he had realized.

Trungpa contemplated the possibility that he had failed. Americans could take to Buddhism, certainly; they would devour it and digest it, and then regurgitate it as psychobabbling New Age pablum. And what was he doing in his adopted country? Trungpa mused possibly that he was the most American of all Americans, of those people who had populated a continent by constandy uprooting themselves and resettling, uprooting and resettling. It seemed that he had experienced this restless rootlessness himself since year one, since before he could remember, when he lost one identity and became the Eleventh Trungpa. He had kept planting the dharma and then having to uproot it, in one country after another, on one continent after another, first in Tibet and then not in Tibet, then in India and then not in India, in England and not in England, and now in America, which may not be his final settling place after all. The weariness of generations overtook him. By the early 1980s his speech became slurred, long pauses interrupted his talks, he sniffled constandy he was a man visibly sick. The alcohol was killing him, yet he refused to stop drinking. Life at all costs had never been Trungpa s criterion. He had accomplished so much, and he did not care for its prolongation in the indignity of a rehab program. He summoned his inner resources, though, to make one last effort and to replant the dharma again, this time in a safe country where it could withstand the rough winds of change to come.

In Thunder and Ocean (1996) the Canadian journalist David Swick shows that the province of Nova Scotia where Trungpa transferred his organizational headquarters, despite its McDonalds restaurants and American- sounding speech, was then genuinely another country. Relocating there,

Trungpa was not hunting new worlds to conquer but a way out, out and into a less modern and more traditional manner of life. Trungpa was not thinking small: He was envisioning the next thousand years, and he now deemed a safe, protected environment necessary for entrenching Buddhism in the Western Hemisphere.

Possibly he felt by then the need for such an environment himself: The oldfangled pace of Nova Scotia might prove restful, a couch on which his body, which was visibly wearing out, could recuperate. A month after moving to Halifax, however, he suffered a heart attack, and for seven months he hung on in a “semi-coma,” though seemingly aware and at peace. On April 4, 1987, four days shy of the Buddha’s birthday, he died, age forty-seven.The master was dead, and a silence descended, with many wondering whether the whole wondrous magical show was over.

Subsequently traumatized by the Thomas Rich scandal, Trungpa’s Buddhist organization ceased its rapid expansion, some members acting as if they had a secret or wrong to hide. Yet ifTrungpa was “wrong” about anything fundamental, it was—not about psychology—but misjudging the extent and durability of his own work. He had founded nearly a hundred centers, he had attracted thousands of students, and his writings had introduced Westerners to Tibetan Buddhism by the hundreds of thousands. Despite certain reservations about his conduct, Helen Tworkov, the editor of the Buddhist magazine Tricyde, judged that “Trungpa was the most effective [religious] teacher, the greatest comet, ever to pass through America.” Even mainstream Christian churches and Jewish synagogues were emulating the Buddhist-style meditation Trungpa taught, teaching practices like mindfulness, and employing Buddhistlike approaches to direct experience. During the Merwin controversy, Allen Ginsberg had joked that Pandora’s Box “has been opened by the arrival in America of one of the masters of the secrets of the Tibetan Book of the Dead. … We might get: taken over and eaten by the Tibetan monsters.” It was meant as a joke, but was the joke coming true?

A DRAMATIST MIGHT HAVE invented Chogyam Tningpa and. Lama Yeshe as a study in contrasts. One of them lived untouched by controversy, while controversy was the very water in which the other swam. One never touched alcohol or women, and the other never stopped touching them. One went around, strikingly, in traditional lama’s robes, while the other looked more striking for having donned a business suit. Yet, as the furor of that period recedes, those two men now seem strangely akin—two unlikely brothers. At nearly the same moment they both fled Tibet, to save their faith (and their lives), and traveled to the unknown, and both insisted on all calling the unfamiliar Home. Each brought with him from Tibet—it was about all he brought—religious precedents and dogmas, yet instead of preaching them each man taught spontaneously out of himself, to meet whatever the new situations demanded. They died at nearly the same age, and during their abbreviated life spans each accomplished prodigious missions despite grave physical handicaps (a fatal heart condition in one, partial paralysis in the other). Before their deaths they had sowed Tibetan Buddhism in America and Europe on a scale undreamed of previously. Subsequendy nobody has replicated their achievements, nor needed to: Later Tibetan lamas arriving here found the soil by them already prepared.

“The

perfect among the sages is identical with Me. There is

absolutely no difference between us”

Tripura

Rahasya,

Chap

XX, 128-133