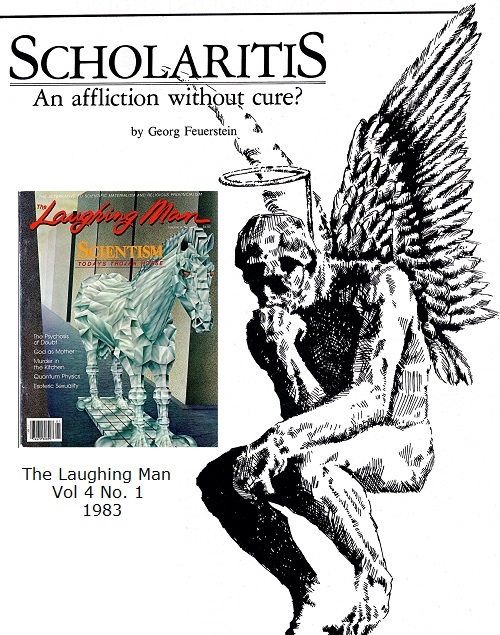

Scholaritis

An affliction without a cure?

“The world’s great men have not commonly been scholars, nor its great scholars great men. ”

Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table

“The world’s great men have not commonly been Adepts, but its Adepts have always also been great men. ”

Anonymous

Scholaritis is a malady that is peculiar to a particular type of personality. As an occupational disease it is widespread among the group of professionals who work in what is known as “the academic world.” That this ailment is not to be found in any of the medical textbooks is itself indicative of the seriousness of this chronic, epidemic-like disease.

What, then, is the symptomatology of scholaritis? First of all, it must be stated that the disease afflicts the body-mind as a whole, leading to particular cognitive and affective distortions that may be characterized as “life-alienation” and “abstract thinking.” The diseased typically tends to emotionally dissociate from, even be fearful of, the experiential building-blocks of sentient existence— touch, sound, smell, sight, taste, and higher sensory inputs. Instead, he is largely transfixed in the realm of “pure” thought, of logical thinking. He prefers concepts to feelings, abstract ideals to the chaos of experience, neat formulas to the aesthetics of the senses, mathematical precision and predictability to biological organicity, controlled experiments to real life situations, computable quantities to intangible qualities, conventionalism to creativity, and theory to practice.

This is combined with an exaggerated (irrational) belief in the salvatory power of rational knowledge through perpetual scientific progress and a paranoid attitude about the unknown or the mysterious as well as about such intangible processes of the human mind as spontaneity, belief, intuition, ESP, and the immediate apprehension of Reality.

Scholaritis, in other words, incapacitates the right cerebral hemisphere and overstimulates the left side of the brain. Thus, those who are affected by the disease not only behave as if they were disembodied minds, but even their disembodiment is limited to only one half of the brain (which they confuse with the mind itself). This self-mutilating lobotomy, which leaves intact only the verbal-logical capacities, reduces the diseased to the functional status of a robot whose rational functioning is, however, still annoyingly handicapped by irrational, redundant emotions Man the imperfect biocomputer.

The disease derives its name from the personality type and professional category with which it is commonly associated—the scholar. It is interesting to note that there are specific terms by which scholars refer to themselves and which reflect their reduction-istic model of Man (and hence self-image). Foremost among these expressions are “brain” (as in “brain drain,” or “brain trust”), “egghead,” or the collective “think tank.”

I have already indicated that scholaritis is an epidemic, even though its precise distribution throughout the world—and there is no doubt that it is rampant globally—is difficult to assess. However, the Directory of American Scholars lists over 38,000 scholars for the United States and Canada alone, which should give one an indication of the potential total spread of the disease. Moreover, there are definite signs that it is highly infectious. In a less acute but nonetheless crippling form it is manifestly present in vast numbers of non-scholars. The mechanisms of transference are primarily the educational system and the mass media.

The foregoing is obviously a caricature, but as with all caricatures, the underlying reality is clearly recognizable. What that reality is can be gleaned from any University curriculum and any of the countless publications that annually contribute to the knowledge explosion (and, incidentally, erase whole forests). More than that, the effects of “scholaritis” can be witnessed in all domains of modern life, via the impact of technology.

Another name for “scholaritis,” particularly when its mass-cultural impact is being considered, is scientism. Scientism is surrogate (ersatz) science. It is the vulgarization of the scientific enterprise which, in itself, is a valid (if limited) form of enquiry into the nature of the universe. Unlike authentic, buoyant science, scientism is not so much an approach to knowledge but primarily an ideology—the antimetaphysical metaphysics of materialism. It is a neurotic, depressive view of man and the world, and it is both partial cause and symptom of our ailing civilization. The Indian social philosopher Radhakamal Mukerjee expressed this poignantly thus:

“Modern scientism or positivism left civilization without a guide for its goals and strivings. The vacuum was filled up by mass passions, hatreds, aggressions and forces of unreason and irrationality, unleashing social movements that perpetrated cruelty and inflicted suffering, indignity and humiliation on man on a scale never previously experienced in the entire history of civilization. The role of value-free social scientism or positivism cannot be lightly treated in the contemporary tragedy of mass human rebarbarization that shocked the whole world in the present generation.” 1

1. R. Mukerjee, The Sickness of Civilization (Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1964), p. 32.

Mukerjee, who was a former Vice-Chancellor of Lucknow University (India), used the past tense to refer particularly to the savagery of Nazi imperialism. However, as is clear from the rest of his cosmopolitan book, the harmful effects of scientism reach beyond that sinister period of German history and beyond the locality of Europe. Nor is the fact of the inherent destructiveness of scientism in dispute. More than any other “ism,” it has contributed to our contemporary self-defeating cynicism and demeaning of what is noble in Man, and it informs capitalism as much as it does communism. All those who have diagnosed this fateful disease correctly are agreed that a cure must be found if mankind is to survive into the twenty-first century. What that cure might be is still regarded as an open question by most (and, as will be shown, wrongly so). Since answers that come from within the scholarly (or scientific) community are likely to be infected by the virus of scientism, they are immediately suspect, either in part or in full. (I was told once that doctors tend to be poor diagnosticians of their own illnesses.) Nor can one expect the so-called “layman” to conceive of a viable solution, especially in view of the fact that, by now, he is apt to have the disease himself.

But there is also no need to call on the layman’s commonsensical wisdom, nor do we need to entrust our destiny to the hands of scientists, although this is what they are asking us to do. A cure has already been found, an antidote to scientism is available. However, it is bound to be highly unpopular, in particular among those who are mainly responsible for the outbreak of the epidemic in the first place. No, we do not need to put an embargo on the scientific enterprise as a whole, or condemn scientists to agricultural labor. The cure is in principle very simple. Aided by corresponding institutional changes (which, I am aware, are notoriously difficult to implement), it attacks the problem at its root—the self-serving nature of scholarship or scientific work. More specifically, it concerns Man’s learned disposition of egoism. (It always comes back to this!) Now, since all men are selfish and scholars are men, therefore—prepare yourself for the shock— all scholars are selfish. The truth of the conclusion of this syllogism is dependent on the truth of the initial generalization of the premise. Are all men really selfish, then? Are there not some scholars who, like Pierre and Marie Curie, have driven themselves to benefit the whole of mankind? Were they not genuinely altruistic? What about Alfred Nobel, who bequeathed nine million dollars, the interest on which has been paying for, among others, the yearly Nobel Peace Prize since I90I? What about Louis Pasteur? Or Albert Einstein?

Without meaning to detract in any way from the magnificent contribution of these giants of science to Man’s cultural heritage, they all have a skeleton in the cupboard. Even the greatest humanist and altruist has to own up to this truth. The skeleton is of course the independent seif-sense, better known as the ego. Egotism and altruism are simply extremes on a spectrum of possible attitudes to life which are all ego-based. Popular consciousness, educated to glorify the scientist who, after all, has made today’s technological miracles possible, believes in the science-created fairytale of “objective” research. Despite plentiful evidence to the contrary, the scientist is still largely seen as a superintelligent being who, pushing aside all personal likes and dislikes, is wholly dedicated to the single-minded pursuit of knowledge. Nothing could be further from the truth. As Professor C. H. Waddington remarked:

“It is time, in fact, that scientists become willing to state explicitly that the scientific attitude is as full of passion, as much a function of the whole man and not merely of an intellectual part of him, as any other approach to human action.”2

There is no need to dwell on the failure of individual scientists, or science in general, to live up to the myth of unsullied objectivity, pure knowledge. Philosophers of science— who are yet another breed of scholars—have waxed eloquent on those particular shortcomings. If we can agree that scientists are indeed human, would it be going too far to suggest that they may also partake of the neuroses that beset the vast majority of ordinary men and women? Could the obsession with objective data, demanding in principle the scientist’s withdrawal from the observed realities into a position of experimental voyeurism, possibly be a rational dramatization of his neurotic need to inhabit a safe ivory tower?

2. C. H. Waddington, The Scientific Attitude (West Drayton, England: Penguin Books, 1948), p. 33.

3. Da Free John, Nirvanasara (Clearlake, Calif.: The Dawn Horse Press. 1982).

My firsthand experience of the kind of personalities that tend to congregate in the halls of academia, as well as self-observation, does seem to lend itself to such an interpretation.

Scientists, scholars, academics, eggheads—whatever you may wish to call the left-brained workers of our human family— are, like all other human beings, thoroughly self-possessed. Maybe, because they are endowed with above-average verbal intelligence, they are more self-possessed than most people, though who would dare cast the first stone since we are all sitting in the same glass house?

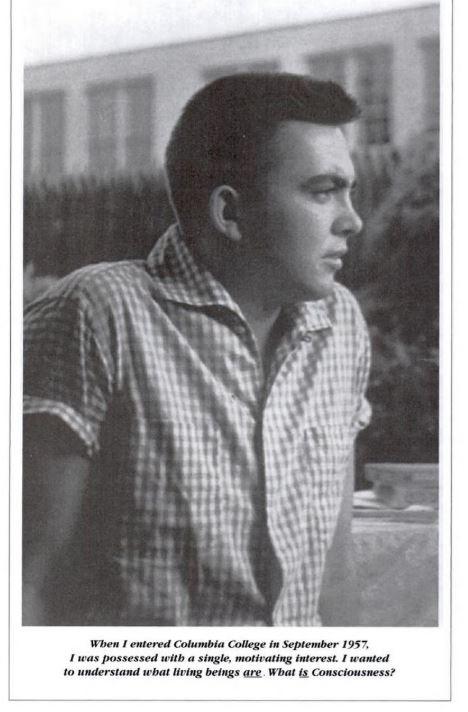

To what extent this held (and unfortunately still holds) true of myself was revealed to me within the first few months of my joining The Johannine Daist Communion. Although I did not get to meet Master Da Free John personally for many months, fairly soon after my arrival at The Mountain of Attention Sanctuary in northern California, he began to engage me in a Teaching consideration that was directly aimed at my “scholarly” approach to writing and to life itself—notably spiritual life. In reviewing my introduction to Nirvanasara? Master Da addressed in particular one cautionary comment I had made.

Considering how some of my former colleagues, who were already puzzled by my plunge into a nonobjective, “committed” way of life, might react to this extraordinary book, I feared that they would immediately question Master Da’s sophisticated style. I tried to anticipate their criticism and doubt. In all honesty, I myself found it at least surprising that an Adept should avail himself of the kind of sophisticated technical language and exposition as embodied in Nirvanasara. After all, spirituality and intellectual ability seem to be mutually exclusive. Or so the story goes.

Master Da, in his communication to me, was quick to point out that I was obviously taking far too seriously the widely-shared opinion that Adepts are incapable of sophistication. He remarked that this is purely a conceit among scholars who take their own profession very seriously and seek to protect it from interference by the Adepts. It is in the interest of scholars, he continued, to entertain the myth of the Adept as a naive country bumpkin. He commented that although some Adepts may start out illiterate, they quickly acquire such sophistication in their interaction with devotees. He cited Ramakrishna as a case in point; although he could not write, he communicated a verbal teaching that was very sophisticated. Self-Realized Adepts, he further stated, are generally very sophisticated intellectually, as can be seen in the example of Ramana Maharshi. I could only agree.

Having been born in the West and having received a university education. Master Da, moreover, brought an uncommon articulateness and fine-tuned mind to his Teaching Work from the very beginning. However, the obvious sophistication demonstrated in his written and spoken Teaching is not a product of mere intellectual learning. In this connection, Master Da remarked that in high Adepts the brain functions (literally) differently, and that Adepts operate from within a different frame of consciousness. (I am only now beginning to appreciate this fact.)

And then he made two points that struck me as so perfectly obvious and cogent that I wondered how they could not have occurred to me independently. In his own case, Master Da went on, he has appeared in a time in which the very possibility of spiritual life is being systematically undermined by a sophisticated literate culture. Therefore, in order to be of service at all, the Adept born into such a situation must be able to avail himself of the left-brain, written modes of communication. He further observed that he had no vital spiritual tradition to fall back upon and consequently the whole matter of spiritual life had to be newly argued. A second reason for his written Teaching is, he explained, the need for his Teaching to be passed on faithfully to future generations, without the risk of being modified and distorted in the process of transmission.

Around the same time I received another (to me, crucial) message from Master Da. In this communication he addressed an intellectual (and emotional) difficulty I was experiencing with his unique biography. I could not reconcile Master Da’s self-confessed Enlightenment from birth with the fact that he spent many years seeking to recover the Transcendental Consciousness that he had apparently lost during his adolescence. I sought to reinterpret these facts along lines that I considered to be more plausible and acceptable. In other words, I was engaged in a surreptitious “demythologization” program. However, as the Adept Da Free John made clear to me, I was by no means undercutting any myth, or even clarifying any possible misunderstanding about his biography. On the contrary, I was creating a myth out of the facts of his life only because they did not fit into my preconceived universe. In rectifying my mistaken assumptions about his life, he introduced me to a way of looking at the world which takes cognizance of its psycho-physical character.

He roundly criticized me for doing fieldwork rather than practicing the Way that he Teaches. Once it was pointed out to me, I could not deny that I was mightily resisting the spiritual discipline I had voluntarily chosen. I was indeed defending myself against the Adept’s demand for egotranscendence and self-surrender. My defense followed the strategy I had always employed with seeming success—to conceptualize rather than whole-bodily embrace reality or life. At the same time, I was still anxious to explain this Teaching and the Adept in terms that other scholars would find, if not acceptable, at least true to the expected norm. Again Master Da hit the nail on the head when he observed that trying to make the Adept and this Teaching acceptable to the usual round of Western scholars is “a little bit like trying to persuade the Ku Klux Klan to elect a black man to be the next Grand Wizard.” I had, he continued, that kind of egg-on-his-face self-consciousness of someone actually nominating a black person at a Ku Klux Klan convention. He said that I was attempting to paint the black person’s face white in the irrational hope that this would lead to a more positive response. He assured me that it would not have the desired effect as, in the meantime, I had the opportunity to discover for myself. Scholars operate from within a set of powerful presumptions that channel their perceptions and force them to reinterpret or deny all evidence that runs counter to their beliefs and expectations.

Master Da’s criticism of me was strong and, as always, to-the-point and compassionate. He simply reflected my dilemma back to me, to be inspected in the broad daylight of consciousness. His criticism dredged up the subconscious resistances I felt at the time. I recognized that by sheer force of habit I had been imposing unnecessary limitations on myself and my work. Thanks to Master Da Free John’s graceful and timely intervention, a new response to the Adept and the Teaching became possible.

I do not presume that I have been cured of scholaritis. The virus is undoubtedly still present in my system; lifelong habits die hard. But being aware of my susceptibilities, I have now the means of transcending my particular cast of Narcissus. And the choice is with me every single moment of my life. I can either contract into self-possession or relax into self-transcending surrender. The self-possessed individual is always fearful of surrender. Yet, as Master Da Free John made clear to me, “the real question is not whether or not to surrender, but what or whom to surrender to.” Scholars, he pointed out, are already surrendered. They have submitted to their own minds. “They are already worshippers in the style of Narcissus. So they suggest that there is something wrong with surrendering, and they do not realize that they are themselves guilty of surrendering to a false idol and already suffering the consequences of false worship.”

I did say the cure for scholaritis is simple, in principle. It is also simple in practice. However, one must be willing to “objectively” reexamine the structures that define one’s personality and ultimately shape one’s destiny. Scholars should be singularly well-equipped to embark on such “objective” research. Only thus will they ever be in a position to truly serve mankind.

THE LAUGHING MAN editors are searching for a needle in the proverbial haystack. More precisely, we are looking for a pen complete with a creative professional writer.

He or she should be acquainted with, and appreciative of, the Teaching of Master Da Free John and be willing to surrender his or her literary skills and versatile knowledge into the fire of the spiritual process.