‘So then, brethren, we are not children of the bond-woman, but of the free.

‘So then, brethren, we are not children of the bond-woman, but of the free.

Epistle to the Galatians, IV. 31.

***

This is a shortened (and highlighted) version – Read the Full Discourse

***

……Relying on the candor which I need from my present auditory, I address myself more particularly to the design of our coming together.

A manner of address calculated to inflame the passions would neither become my station, nor be respectful to an audience well acquainted with the rights of men and citizens, educated in principles of liberty.

The Africans belong to the families for whom heaven designed a participation in the blessing of Abraham. We need not discuss the question, what the state of those, whom the Europeans have enslaved, was antecedently to such their slavery. It is more proper to enquire when and how the African slave-trade commenced—what nations have engaged in it—in what manner they have carried it on —what the probable numbers they have reduced to slavery—in what condition these slaves are held—and what reasons are offered in vindication of the trade.

A zeal for the discovery of new territory marked the fifteenth century.

The first navigations of the Europeans for this purpose were concerted and directed by prince Henry, fourth son of John I. king of Portugal. He was born 1394. His valor in the assault and capture of the city Ceuta in Africa, A.D. 1415, presaged the fame he afterwards acquired. From this period he devoted himself to naval expeditions for the discovery of unknown countries.

The ships he sent out subjected divers parts of Africa, and the neighbouring islands, to the dominion of Portugal. After the success in doubling cape Bojador, he gave to his father and his successors all the lands he had discovered, or might discover, and applied to pope Martin V. to ratify the donation. He engaged, that in all their expeditions the Portuguese should have mainly in view the extension of the Roman church and authority of its pontif. Martin granted the prince’s request. In his bull of ratification, which was about the year 1430, it is declared, that “whatever might be discovered from the said cape to the utmost India, should pertain to the Portuguese’ dominion.”

Edward, brother to prince Henry, succeeded to the throne of Portugal 1433, on the death of John I. Pope Eugene IV, by his bull in 1438, ratified to Edward the grant made by Martin V. A bull of Nicholas V. dated January 8, 1454, refers to the aforesaid bulls of his predecessors, Martin and Eugene. It recites the declaration prince Henry had made of his achievements —

“that for 25 years he had not ceased to send annually almost an army” of Portuguese, “with the greatest dangers, labors and charges, in most swift ships, to search out the sea and maritime provinces towards the southern parts and antarctic pole”

—that these ships “came at length to the province of Guinea, and took possession of some islands, havens and sea adjoining”—that “sailing further, war was waged for some years with the people of those parts, and very many islands near thereunto were subdued and peaceably possessed, and still were possessed, with the adjacent sea”—that “many Guineans and other negroes were taken thence by force, and some by barter.”

The bull describes prince Henry as “a true soldier of Christ, a most courageous defender and intrepid champion of the faith, aspiring from his early youth with his utmost might to have the glorious name of Christ published, extolled and revered throughout the world.”

It recogniseth the exclusive right of Portugal to the acquisitions and possessions aforesaid, in virtue of the letters of Martin and Eugene, which granted to the king of Portugal and prince Henry “free and ample faculty to invade, search out, expugn, vanquish and subdue all pagans and enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and their persons to reduce to perpetual slavery, and all their kingdoms, possessions and goods to apply and appropriate,” &c.

Pope Nicholas’s letter then goes on to “decree and declare, the acquests already made, and what hereafter shall happen to be acquired, after that they shall be acquired, have pertained, and forever of right do belong and pertain, to the aforesaid king and his successors, and not to any others whatever.”

It forbids, on the severest penalties, all Christian powers from settling in the countries discovered by the Portuguese, or any way molesting them in their expeditions for the discovery and conquest of unknown countries. It speaks of prince Henry’s plan and his prosecution of it as “a most pious work, and most worthy of perpetual remembrance, wherein the glory of God, with the interest of the commonwealth of the universal church are concerned.”

Thus were prince Henry’s views and operations sanctioned by the highest authority at that time acknowledged in Christendom. A right derived from a source so venerable was then undisputed. The Roman pontif bound princes at his pleasure; and, as vicar of Christ, was allowed to have at his disposal all the kingdoms of the earth. This grant of Nicholas was confirmed by his successor, Calixtus III. August 6, 1458.

On the death of Edward, his son Alphonsus, then in his minority, succeeded to the throne of Portugal 1438, and died 1481. Prince Henry died 1460, or 1463. At his death the spirit of discovery languished; but revived with the accession of John II. son of Alphonsus. John, the year after his accession (1482), sent an embassy to Edward IV. of England, to acquaint him with the title acquired, by the pope’s bull, to the conquest in Guinea; and requested him to dissolve a fleet which some English merchants were fitting for the Guinea trade.

The king of England shewed great respect to the ambassadors, and granted all they required. The king of Portugal assumed, and the king of England gave him, this style, Rex Portugalice et Algarbiorum citra at ultra mare in Africa. Pope Sixtus IV. not long before his death, which was August 12, 1484, confirmed all the grants made by his predecessors to the kings of Portugal and their successors.*

“In 1481 John II. sent 100 artificers, 500 soldiers, and all necessaries, to build a fort in Guinea. The large kingdoms of Benin and Congo were discovered 1484, 1485”; and the cape of Good-Hope 1486. The Portuguese built forts and planted colonies in Africa; “established a commercial intercourse with the powerful kingdoms, and compelled the petty princes by force of arms to acknowledge themselves vassals.” At this period, and by these means, the power and commerce of the Portuguese in Africa were well established.

The wholesome decrees of five successive Roman pontifs granted, conveyed and confirmed to the most faithful king a right to appropriate the kingdoms, goods and possessions of all infidels, wherever to be found, to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, or destroy them from the earth, for the declared purpose of bringing the Lord’s sheep into one dominical fold, under one universal pastor.

Succeeding kings of Portugal have not forfeited the large grant by any undutifulness to their holy father. Portugal long enjoyed the trade to Africa and the East-Indies without the interference of any European power. For more than half a century before she exported any Negroes from Africa, she made and held many of them slaves in their native country.

The Portuguese first imported slaves into Hispaniola, A.D. 1508, and into their Brazilian colonies 1517.$ Their sugar works were first set up in these colonies 1580. Their union with Spain at that time was most unfortunate for them. Hence the Dutch became their enemies, who took from them their East-India and Brazilian conquests, and part of their African colonies. They recovered Brazil, and their African establishments 1640; but have never recovered the riches of India. It is observable, that the island which first received slaves from Africa, suffers at this time (October 1791) the most exemplary and threatning vengeance from them. How perilous such property!

* Plantation of colonies, part I. sect. 26.

$ Brazil was discovered A.D. 1500, by Cabral’s fleet, fitted out by John II. king of Portugal.

After the Dutch quitted Brazil, and the gold mines were discovered, the trade of Portugal improved, and a great importation of slaves took place. “They carry yearly from Loango to the Brazils 25,000.” At Goango “they get abundance.” At Cape Lopos they “get a great many.” They themselves say, “that they carry over to Brazil 50,000 and more every year from Melinda” on the Mozambique coast. Such hath been the increase of their Brazilian and African colonies for about a century past, that they “have taken off since the year 1700 more English goods annually than Portugal and Spain had before done.”[*] From their greater dominions, and greater extent of territory, in Africa, than any other European power, this quarter of the world “is not of less consideration to them, perhaps, than to all the other powers of Europe unitedly comprehended—It supplies them with Negroes in abundance, to carry on their sugar works, mines, and planting business in the Brazils.t They are said to bring annually from the Brazils £.5,000,000 sterling in gold, coined and uncoined.”$

t Postlethwait, assiento.

$ Anderson’s commerce, vol. II, p. 156:

* Postlethwait, vol. II. p. 766.

[*] Postlethwait, vol. I, tit. Brazil.

t Ibid. vol. II. p. 521-524.

Beawes saith (Lex mercatoria), that the trade for slaves at Senegal “amounts to 15,000 in a common year.” (p. 726.) At Sierra Leona “the trade in slaves is not a little.” (p. 728.) At Des Trois Pointes the Dutch trade for “many slaves.” In the kingdom of Ardres, &c. between three and four thousand are annually purchased, (p. 729.) On the coast of the kingdom of Benin, at Sabe, the English, French, Dutch and Portuguese “export annually above 20,000.” (p. 730.) “The number sent from Congo by the Portuguese is surprizingly great.” (Ibid.)

“Of all the African coasts, Angola furnisheth the Europeans with the best negroes, and commonly in the greatest quantities. Though the Portuguese are extremely powerful in the interior parts of this kingdom, yet the negro trade on the coast is free to other nations. The English, French and Dutch send yearly a great number of vessels, who carry off many thousands for their American settlements, and for sale in those of the Spaniards. There is hardly any year that the Portuguese do not ship off 15,000 for Brazil. The villages of Cambambe, Embaco and Missingomo furnish most slaves to the Portuguese merchants”—the negro trade at Longo, Malindo and Cabindo, on the Angolian coast, is not one of the least considerable that the English and Dutch are concerned in, whether for the number, strength or goodness of the slaves—the inhabitants of the American colonies always give for them an higher price, as more able to sustain the labours and fatigues of the culture and manufacturing of sugar, tobacco, indigo, and other painful works.” (p. 731.)

“It is difficult to ascertain the number of slaves, which the Portuguese residing in Africa have in possession. Those who are least rich have fifty, an hundred, or two hundred belonging to them, and many of the most considerable possess at least three thousand. A religious society at Loanda have of their own 12,000 of all nations.” (Beawes, lex mercatoria, p. 790, 791.)

Spanish America hath successively received her slaves from the Genoese, Portuguese, French and English. A convention was made at London between England and Spain, A.D. 1689, for supplying the Spanish West-Indies with negro slaves from Jamaica.[†] The French Guinea company contracted, in 1702, to supply them with 38,000 negroes, in ten years; and if peace should be concluded, with 48,000. In 1713 there was a treaty between England and Spain for the importation of 144,000 negroes in thirty years, or 4,800 annually.! If we include those whom the Portuguese have held in slavery in Africa, with the importations into Sou th-America, twelve millions may be a moderate estimate from the commencement of the traffic to the present time.

[†] Anderson’s commerce, vol. V. p. 120.

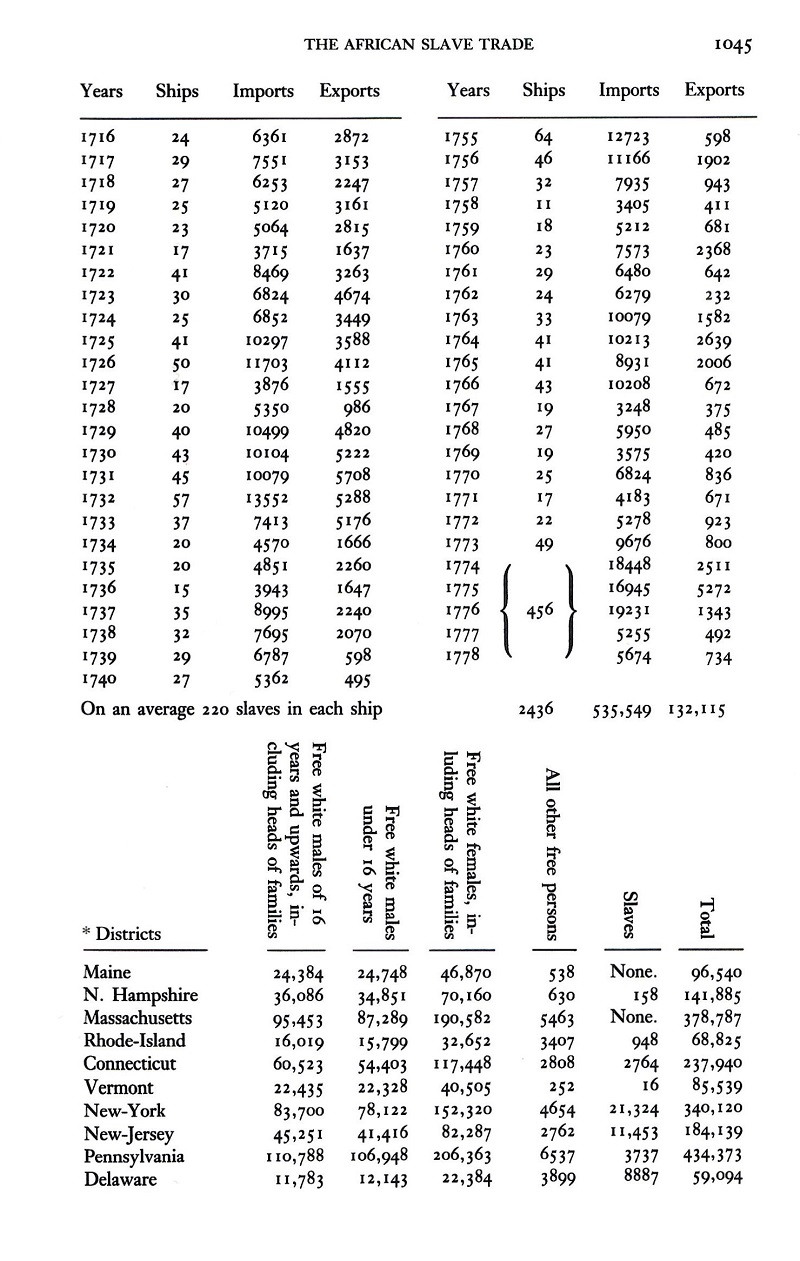

We shall now attend to the importations into the West-India islands and the United States.

The English fitted out three ships for the slave trade in 1562.$ For a full century this trade hath been vigorously pursued, without intermission, by England, France and Holland; as it had been long before, and continued to be, by Portugal.

“The trade of Barbadoes, in 1661, maintained 400 sail of ships of 150 tons one with another, and 10,000 seamen. The running cash was computed at £.200,000 at least. In 1676 this island had 80,000 negroes. In one hundred years the inhabitants of Great-Britain have received £.12,000,000 in silver by means of this plantation. On a parliamentary enquiry into the African trade 1728, it appeared that in three years only, 42,000 slaves had been imported at Barbadoes, Jamaica and Antigua, besides what were carried to their other islands.

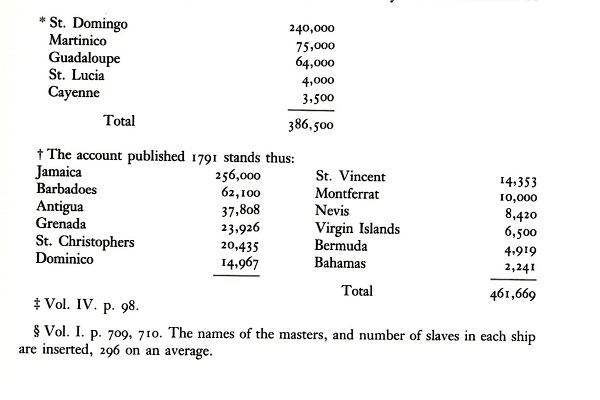

In pursuance of an order from the king of France, a survey was made in 1777, of the slaves in the French islands, when the number returned was 386,500.* The council of Paris determined, that an annual importation of 20,000 was necessary to supply the annual decrease. (Anderson, vol. V. p. 276.)

The number of slaves in the several British West-India islands is stated by Anderson at 410,000, (vol. VI. p. 921, 922.) A later account makes them 461,669.1

“Since the peace of 1763,” saith M. Ie Abbe Raynal,± “Great-Britain hath sent annually to the coast of Guinea 195 vessels, consisting, collectively, of 23,000 tons, and 7 or 8,000 seamen. Rather more than half this number have sailed from Liverpool, and the remainder from London, Bristol and Lancaster. They have traded for 40,000 slaves.” An average for each vessel will be 205. Postlethwait informs us, that in 1752 eighty-eight vessels from Liverpool to Africa brought away 25,940 slaves.§ If the Liverpool vessels brought away this number, we may suppose that those of London and Bristol made up the full number of 40,000.

M. le Abbe Raynal saith (probably without sufficient attention, vol. IV. p. 99.), “The trade of Africa hath never furnished the French colonies more than 13 or 14,000 slaves annually.” This importation, he grants, was “insufficient” for her colonies. It doth not correspond to the number of slaves in them. If the trade had not furnished a sufficiency for themselves, would they have contracted to supply Spain with 4,000 slaves annually for ten successive years? “Good judges,” saith Postlethwait (vol. I. p. 726.), “reckon that 30,000 negroes are annually imported into the French sugar islands.” But we will suppose they import 20,000 into these islands. This is the importation which their council supposed requisite to supply the decrease. The general computation is five percent, decrease annually.

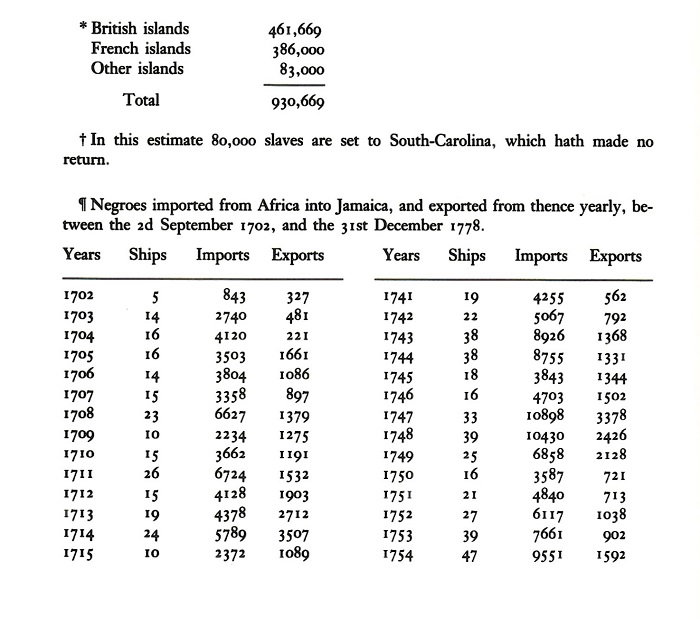

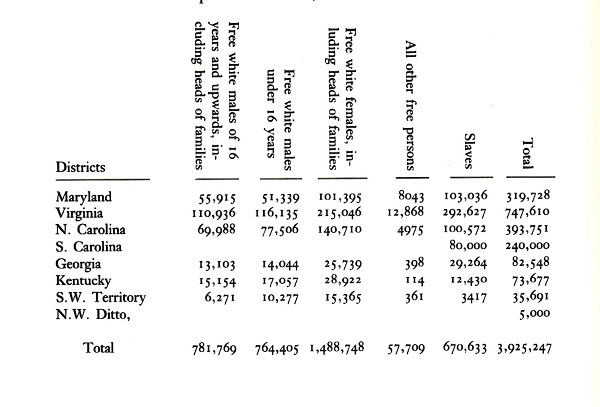

The present number of slaves in the West-Indies is 930,669.* There are in the United States 670,633.1 To this number may be added about 12,000 manumitted Africans. In all 1,613,302. Were the mortality among them as great in the five states south of Delaware as in the West-Indies, the above number could not be kept up but by an annual importation of 80,000. The probability is, that 70,000 hath been the annual average for a century at least.

In seventy-seven years there were imported into Jamaica 535,549.^ By the census of the United States, taken 1791, they contain 3,925,247 souls.* Of these, in the states south of Delaware, more than one quarter are negro slaves. In the four states next north of Maryland are 45,401 slaves. In New-England 3,870. There may have been brought into all the West-India-Islands, and into the United States, from first to last, seven millions. One million more must be allowed for mortality on the passage. How many have been destroyed in the collection of them in Africa, we cannot justly conjecture. It is judged that Great-Britain sustain the loss of twice as many seamen in this, as in all their other extensive trade.

Twenty Million Slaves

We suppose, then, that eight millions of slaves have been shipped in Africa for the West-India islands and the United States; ten millions for South-America; and, perhaps, two millions have been taken and held in slavery in Africa. Great-Britain and the United States have shipped about five millions, France two, Holland and other nations one; though we undertake not to state the proportion with exactness. The other twelve millions we set to Portugal. Twenty million slaves, at £.30 sterling each, amount to the commercial value of £.600,000,000. Six hundred times ten hundred thousand pounds sterling traffic in the souls of men!!!

By whom hath this commerce been opened, and so long and ardently pursued? The subjects of their most faithful, most catholic, most Christian, most protestant majesties, defenders of the faith-, and by the citizens of the most republican States, with the sanction of St. Peter’s successor. Unprovoked, without any pretended injury, these have kindled and kept alive the flame of war through three quarters of the continent of Africa; that is, all the interior as well as maritime parts south of Senegal and Abyssinia. These have taught the Africans to steal, sell and murder one another. On any or no pretence the different tribes make prisoners of each other, or the chiefs seize their own people, and drive them, as herds of cattle, to market. The natives are trepanned by one another, and by the Europeans; forced from their flocks, and fields, and tenderest connexions. This vile commerce hath depopulated the sea-coast: It must now be carried on in the inland parts.

As though it were not sufficient to force the Africans from their country, and every thing dear to them, they are made to travel in irons hundreds of miles through their native soil, through sands and morasses, down to the sea shore; and there stowed, as lumber, for transportation. The cruelty of the captains of the Guinea ships, in many instances, is not inferior to that of Clive or Hastings.

The servitude of the greatest part of the slaves after their arrival, the scantiness of their provision and its bad quality, their tyrannical and merciless discipline, are well known, and too painful to recollect. It is a law in Barbadoes, “that if any slave, under punishment by his master or his order, suffer in life or limb, no person shall be liable to any fine for the same. But if any man shall wantonly or cruelly kill his own slave, he shall pay into the treasury £.15.”

With what reason or truth is it urged, that the condition of the Africans is meliorated by their slavery? They, not their masters, are the proper judges in this matter. Wretched as you may suppose their condition was in Africa, the nefarious commerce of foreigners may have been the principal cause of that wretchedness. Should foreigners desist from this commerce, and the holders of slaves propose to transport them back to Africa, how would their mouth be filled with laughter, and their tongue with singing? Instead of thinking their condition meliorated by slavery, they most sincerely join in that execration on their oppressors: Happy shall he be that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones. The imaginary expectation that death may transport them to their own country is their chief consolation. Under unlimited power, accustomed to the most inhuman usage, no example of mercy relenting for them being exhibited, no marvel that the language of insurgents is, Death or conquest. Their cries will sooner or later reach the ears of him to whom vengeance belongeth.

Will any one say, that their condition is meliorated by their being taught the knowledge of God and CHRIST? How many of their masters are in a state of brutal ignorance in this respect? A parish minister[‡] in the West-Indies saith, that he “drew up plain and easy instructions for the slaves, invited them to attend at particular hours on Lord’s-day, appointed hours at home, and exhorted their masters to encourage their attendance. But inconceivable was the listlessness with which he was heard, and bitter the censure heaped on him in return. It was suggested, that he aimed to render them incapable of being good slaves by making them Christians—some who approved of the plan, did not think themselves obliged to co-operate: I stood,” says he, “a rebel convict against the interest and majesty of planter ship.”

“I can’t say it from my heart, if I think of white man”

When Archbishop Seeker asked what success the missionaries “had in baptizing and converting negro slaves? how the catechist at Coddrington college in Barbadoes proceeded with those slaves that belonged to the college estate,” and whom he presumed had been instructed in Christianity? He was answered, “I found one old negro, who told me he could say all his catechism. I asked him, if he did not find himself much happier and better since he became a Christian, than he was before? Why, sir, said he, I am old man, and as a driver am not put to common labour; but Christian not made for negro in this country. How so? What is your duty towards God? He repeated it. What is your duty towards your neighbor? Ah, master, I don’t say that no more. Why so? Because, master, I can’t say it from my heart, if I think of white man.”

Had African slaves the means of Christian instruction, had they been treated with humanity, still the making slaves of them hath been no more than doing evil that good may come. Christianity and humanity would rather have dictated the sending books and teachers into Africa, and endeavors for their civilization. Have they been treated as children of the same family with ourselves? as having the same Father, whose tender mercies are over all his works? as having the same natural prerogatives with other nations? Or have they been treated as outcasts from humanity?*

[‡] Mr. Ramsay.

The Greeks and Romans, amidst their improvements in philosophy, arts and sciences, established slavery as far as they extended their conquests. Their rage for conquest had the world for its object. They made war without having received any injury. Captives taken in war were exposed to sale. And indeed all the ancient nations considered conquest as a just foundation for slavery. Some moderns have undertaken to defend the same principle. In an age and country so well acquainted with the rights of men, this kind of reasoning merits very little attention. It is, moreover, wholly inapplicable to the case of African slavery.

* The committee of the society in London, instituted in 1787, for the purpose of effecting the abolition of the slave trade, reported to the society, January 15, 1788, “that sundry specimens evince that a trade of great national importance might be opened by once establishing the confidence of the natives.” The sentiments and reasoning of a great commercial writer on this subject are just and forcible.

“If once a turn for industry and the arts was introduced [into Africa], a greater quantity of the European produce and manufactures might be exported thither, than to any other country in the whole world. No country is richer in gold and silver. Here is a prodigious number of elephants, which would not only facilitate the inland intercourses of commerce, but also, in the teeth of these notable animals, afford a very beneficial branch of commerce. The fruitful rich lands, every where to be found upon the coasts and within the country, upon the banks of the rivers near the gold-coast and the slave-coast, would produce all the richest articles of the East and West-India commerce. It is melancholy to observe, that a country which has 10,000 miles sea-coast, and noble, large, deep rivers, should yet have no navigation; streams penetrating into the very centre of the country, but of no benefit to it; innumerable people, without knowledge of each other, correspondence, or commerce—Africa, stored with an inexhaustible treasure, and capable, under proper improvements, of producing so many things delightful as well as convenient, seems utterly neglected by those who are civilized themselves, and its own inhabitants quite unsolicitous of reaping the benefits which nature has provided for them. What it affords in its present rude, unimproved state, is solely given up to the gain of others, as if not the people only were to be sold for slaves to their fellow-creatures, but the whole country was captive, and produced its treasures merely for the use and benefit of the rest of the world, and not at all for their own. Instead of making slaves of these people, would it not rather become nations, who assume the name and character of Christians, to give them a relish for the blessings of life, by extending traffic into their country in the largest extent it will admit of, and introducing among them the more civilized arts and customs? While the slaving trade continues to be the great object of” other nations, and these “promote the spirit of butchery and making slaves of each other among the negro princes and chiefs, their civilization, and the extension of trade into the bowels of the country, will be obstructed.”

(Postlethwait, vol. I. p. 686; 727.)

Whatever just dominion conquerors may claim over the conquered must be founded in this, that the latter were the aggressors. Did the Africans first invade the rights of the nations who have carried on the slave trade? or give them a foundation of complaint? Were they ever conquered by their foreign invaders?

But the reasoning is not less unjust than inapplicable. The objects of a just war are the security of national rights, and indemnification for injuries. Superior force may enslave, but gives no right. It is inglorious, savage and brutal to insult a conquered enemy, and reduce him to the lowest servility.

“But did not the Jews make slaves of the Canaanites by the express command of God?” They did indeed. Those nations had filled up their measure of iniquity. The Supreme Sovereign devoted them to destruction, and commissioned Israel to be the executioners of his justice. “Thou mayest not,” said God, “consume them at once, lest the land become desolate, and the beasts of the field increase against thee. By little and little will I drive them out from before thee.” Of those nations, remaining in the land, they might purchase bond-servants, and transmit them as an inheritance to posterity. The Gibeonites, one of these devoted nations, obtained a league of peace with Joshua, under pretence that they were a very remote people. When their stratagem was detected, he saved them alive, because of his league; but he made them all bond-men, hewers of wood, and drawers of water (Lev. 25. 44, 45, 46. Joshua chap. 9th). When a like warrant can be produced, it will authorize a like practice.

“But Ishmael was the son of a bond-woman. His posterity therefore can have no claim to freedom.” This is not a just consequence; nor is this objection supported by history. The prophecy concerning Ishmael was, “He will be a wild man; his hand will be against every man, and every man’s hand against him.” His posterity, the Arabians, have lived in war with the world. The Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Tartars and Turks have in vain attempted to subjugate them. They have been and are free and independent.

That the heathen have no right to any possession on earth, is an article of the Roman faith. The charters of Britain to her late colonies held out the same language. But is this the language of him, whose is “the world, and they that dwell therein”? who “hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on all the face of the earth; and determined the bounds of their habitation”? In enslaving the pagans of Africa, have the Christians of Europe and America proceeded on this principle, that the author of their religion, whose kingdom is not of this world, hath commissioned them to seize on the possessions, and, what is more, on the persons, of those heathen? Among the enumerated articles of commerce in mystical Babylon in the day of her fall, slaves and souls of men closeth the account—intimating that this kind of commerce was the consummation of her wickedness. Let such as imitate the example, consider the consequence.

Man’s obdurate heart does not feel for man.

He finds his fellow guilty of a skin

Not colour’d like his own; and having pow’r

T’ enforce the wrong, for such a worthy cause

Dooms and devotes him as his lawful prey.

Thus man devotes his brother, and destroys;

And worse than all, and most to be deplor’d,

As human nature’s broadest, foulest blot,

Chains him, tasks him, and exacts his sweat

With stripes, that mercy with a bleeding heart

Weeps when she sees inflicted on a beast.

Then what is man? And what man seeing this,

And having human feelings, does not blush,

And hang his head, to think himself a man?[§]

[§]Cowper.

Africans are our Brethren

Our late warfare was expressly founded on such principles as these: “All men are created equal: They are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Admitting these just principles, we need not puzzle ourselves with the question, whether a black complexion is a token of God’s wrath? If attempts to account for the color of the blacks, by ascribing it to climate, or the state of society, or both, should not be perfectly satisfactory (and perhaps they are not), shall we therefore conclude, that they did not spring from the same original parents? How then shall we account either for their origin or our own? The Mosaic, which is the only account of the origin of mankind, doth not inform us what was the complexion of Adam and Eve.

If we admit the Mosaic account, we cannot suppose that the Africans are of a different species from us: If we reject it, we have no account whence they or we sprang. Let us then receive the Mosaic history of the creation, till another and better appears. According to that, the Africans are our brethren. And, according to the principles of our religion, they are children of the free-woman as well as we. This instructs us, that God is no respecter of persons, or of nations—hath put no difference between Jew and Greek, barbarian and Scythian. In Christ Jesus, in whom it was foretold “all nations shall be blessed,” those “who sometimes were far off, are brought nigh, and have access by one Spirit unto the Father.” So that they “are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellow-citizens with the saints, and of the houshold of God.” The heathen will all be given him for his inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for a possession.

Why then should we treat our African brethren as the elder son in the parable treated the younger, offended at the compassion of their common parent towards him? Why place them in a situation incapable of recovery from their lost state? their state of moral death? Did Jesus come to redeem us from the worst bondage? Shall his disciples then enslave those whom he came to redeem from slavery? who are the purchase of his blood? Is this doing to others, as he hath commanded, whatsoever we would that they should do to us? Is it to love our neighbour as ourselves?

On a view of the wretched servitude of the Africans, some may suspect, that they must have been sinners above all men, because they suffer such things. This way of reasoning, however common, our Lord has reproved—particularly in the instance of the blind man; of those who were slain by the fall of the tower in Siloam; and of those whose blood Pilate mingled with the public sacrifices. All mankind are the offspring of God. His government over them is parental. Children may have the fullest proof that the government of their father is not capricious and tyrannic, but most wise and kind: At the same time, they cannot explain many parts of it; but unreservedly submit to his pleasure, having the fullest confidence in his superior wisdom, his paternal care and affection.

That such as have been educated in slavish principles, justify and practise slavery, may not seem strange. Those who profess to understand and regard the principles of liberty should cheerfully unite to abolish slavery.

Our middle and northern states have prohibited any further importation of slaves. South-Carolina passed a prohibitory act for a limited time. Consistently with the federal constitution the traffic may be stopped in seventeen years; and a duty of ten dollars may be laid on every slave now imported. By an act of the legislature of Connecticut, all blacks and mulattoes born within the state from March 1784, will be manumitted at the age of 25 years. The act of Pennsylvania liberates them at the age of twenty eight years. Such provision hath been made for the gradual abolition of slavery in the United States. Could wisdom and philanthropy have advanced further for the time?

In the northern division of the United States, the slaves live better than one quarter of the white people. Their masters are possessed of property; nor is harder labor required of the slaves, than a great part of the masters perform themselves. Might the estate of the masters be exempt from the maintenance of their slaves, but very few would hesitate to manumit them.

In co-operating with the wise measures and benevolent intentions of the legislature of Connecticut, we shall do as much as can be desired to ease the condition of slavery, and extinguish the odious distinction. Humane masters, requiring no more than is just and equal, and affording to their servants the means of moral and religious instruction, take the only sure course to make them faithful. Many receive such kind treatment, and have such affection to their masters, that they wish to abide with them. Nor is it to be doubted but many others, who may wish to be manumitted, would soon repent their choice. Still the term slave is odious, be the master’s yoke ever so light. And it is very questionable whether any servant can be profitable who is not a voluntary one.

The revolution in the United States hath given free course to the principles of liberty. One ancient kingdom, illuminated by these principles, and actuated by the spirit of liberty, hath established a free constitution. The spirit will spread, and shake the throne of despotic princes. Neither an habit of submission to arbitrary rule in church and state, nor the menaced interference of neighboring kingdoms, could prevent, or counterwork, a revolution, propitious in its aspect on the rights of other nations, and of mankind. No combination of European potentates can impede the progress of freedom. The time is hastening, when their subjects will not endure to be told, that no government shall exist in any nation but such as provides for the perpetuation of absolute monarchy, and the transmission of it to the families in present possession. The time is hastening, when no monarch in Europe shall tell his subjects, Your silver and your gold are mine.

The present occasion will be well improved, if we set ourselves to banish all slavish principles, and assert our liberty as men, citizens and Christians. We have all one Father: He will have all his offspring to be saved. We are disciples of one master: He will finally gather together in one the children of God. Let us unite in carrying into effect the purpose of the Saviour’s appearance. This was to give peace and good will to man, and thus bring glory to God on high.

Being “one body in Christ, and every one members one of another”; we should take care “that there be no schism in the body.” They who separate themselves, or separate others, without cause, are schismatics. Christ is not divided. A religious party is of all others the most odious and dangerous. The terms express a palpable contradiction. The dire effects of proselyting zeal in Romish, and even in Protestant, countries would have been prevented, had Christian liberty been understood, and the exercise of it permitted.

Whether ignorance or learning, weakness or craft, have bound the heaviest burthens in religion, we need not enquire. Each of them hath done much in this way in ages past. Happily for the present age of light and liberty, the spirit of bigotry and domination cannot encumber and debase Christianity as heretofore. The exercise of private judgment, an appeal to the scriptures, and the cultivation of Christian charity and philanthropy, will display the excellency of our religion.

To conclude: In vain do we assert our natural and civil liberty, or contend for the same liberty in behalf of any of our fellow-creatures, provided we ourselves are not made free from the condemnation and dominion of sin. If there is such a thing as slavery, the servant of sin is a slave—and self-made. The captive, prisoner and slave, in an outward respect, may be free in Christ, free indeed; while he who enjoys full external liberty, may, in regard to his inward man, be under the power of wicked spirits: These enter and dwell in an heart garnished to receive them. Jesus Christ, and no other, saveth from sin and wrath. The spirit of life quickeneth those who are dead in trespasses, and looseth those whom Satan hath bound. “If we be dead with him, we believe that we shall also live with him.”

The new Jerusalem is free in a more exalted sense than the church on earth. True believers, “sealed with the holy Spirit of promise, have the earnest of their inheritance, until the redemption of the purchased possession.” In that day of complete redemption, of glorious liberty, may God of his infinite mercy grant that we may meet all the ransomed of the Lord, with songs and everlasting joy, saying: “Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto him that sit- teth upon the throne; and unto the lamb who was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood, out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation. Amen.”

— Dr. David W. Hall is pastor of Midway Presbyterian Church, Powder Springs, Georgia, and author of over 20 books on theology and church history.

James Dana (1735–1812) graduated from Harvard and was a Congregationalist pastor in Connecticut. He was an early and avid supporter of American independence. Dana became pastor of the First Church of New Haven from 1789-1805, when he was summarily dismissed by the leaders and replaced by the ascendant new preacher, Moses Stuart. He received a D. D. from the University of Edinburgh, and one of his sons, Samuel Whittlesey Dana became a Senator. [Source: consource.org]

This sermon was delivered before the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom on September 9, 1790. It is an early abolitionist address, showing again that the earlier clergy rightly appealed to Scripture but did not avoid current topics as if that was none of the church’s business.

Dana began with an explanation of the setting of Galatians 4:31 in the context of the Bible. He reviewed the Jewish history and stressed that believers in Christ were not descendants of a line of slavery but of freedom. And as the opening verse of the next chapter asserts, believers were to stand fast in their liberty. Freedom was worth defending. He remarked, “Christian freedom, being alike the privilege of converts from Judaism and heathenism, primarily intends, on the part of the former, the abolition of the encumbered ritual of Moses; and, on the part of the latter, liberation from idolatrous superstition, to which they were in servile subjection: On the part of both it intends deliverance from the slavery of vicious passions.”

Christ’s followers, he taught, brought in a glorious age of expansive liberty: ‘His disciples, made free from sin, walk not after the flesh, but after the spirit. There is no condemnation to them. Thus emancipated, they “wait for the hope of righteousness by faith—the redemption of the body.” He added further that Christianity leads its followers to call no man, “master”—the application of which, he preached, would oppose the slave trade (or early Human Trafficking). He also distinguished: “The real friends of liberty always distinguish between freedom and licentiousness. They know that the mind cannot be free, while blinded by sceptical pride, or immersed in sensuality. Liberty consists not in subverting the foundations of society, in being without law. Nor doth it consist in reasoning against God, and providence, and revelation.”

Dana proclaimed that the biblical faith overflowed with “the best aspect on general liberty and the rights of mankind.” “This spirit,” he continued, “doth no ill to others, but all possible good. Rulers, under its influence, are not oppressors, but benefactors.”

Dana did not wish to inflame passions with this address but to appeal to informed consciences. He next provided a detailed history of the colonization of the West, along with a discussion of its religious leadership. He also pointed the finger on the Portuguese (for settling parts of Africa) and various Popes for approving perpetual slavery for certain races. He thought that the exporting of African slaves by the Portuguese began just at the 16th century opened. A sample of his detail is below:

Spanish America hath successively received her slaves from the Genoese, Portuguese, French and English. A convention was made at London between England and Spain, A. D. 1689, for supplying the Spanish West-Indies with negro slaves from Jamaica. The French Guinea company contracted, in 1702, to supply them with 38,000 negroes, in ten years; and if peace should be concluded, with 48,000. In 1713 there was a treaty between England and Spain for the importation of 144,000 negroes in thirty years, or 4,800 annually. If we include those whom the Portuguese have held in slavery in Africa, with the importations into South-America, twelve millions may be a moderate estimate from the commencement of the traffic to the present time.

The British and French colonialists, he said, contributed mightily to this, with his census being: “The present number of slaves in the West-Indies is 930,669. There are in the United States 670,633. To this number may be added about 12,000 manumitted Africans. In all 1,613,302.” He blamed predominantly Christian cultures (“by the citizens of the most republican States, with the sanction of St. Peter’s successor”) for this magnitude of slavery.

We suppose, then, that eight millions of slaves have been shipped in Africa for the West-India islands and the United States; ten millions for South-America; and, perhaps, two millions have been taken and held in slavery in Africa. Great-Britain and the United States have shipped about five millions, France two, Holland and other nations one; though we undertake not to state the proportion with exactness. The other twelve millions we set to Portugal. Twenty million slaves, at £.30 sterling each, amount to the commercial value of £.600,000,000. Six hundred times ten hundred thousand pounds sterling traffic in the souls of men!!!

Dana continued to lament that Christians did not work more zealously for abolition, nor to improve the lives of slaves. Further, he addressed the many OT passages where slavery existed or was not overturned, suggesting mitigating factors for those. Citing the recent language from the Declaration of Independence (“All men are created equal”), he extrapolated that all humans in America were equal and free. He did not believe that Africans were less human or less deserving of all benefits of Christ: “The present occasion will be well improved, if we set ourselves to banish all slavish principles, and assert our liberty as men, citizens and Christians. We have all one Father: He will have all his offspring to be saved. We are disciples of one master: He will finally gather together in one the children of God. Let us unite in carrying into effect the purpose of the Saviour’s appearance.” He called for Christ’s body, the church to be undivided and concluded passionately:

To conclude: In vain do we assert our natural and civil liberty, or contend for the same liberty in behalf of any of our fellow-creatures, provided we ourselves are not made free from the condemnation and dominion of sin. If there is such a thing as slavery, the servant of sin is a slave—and self-made. The captive, prisoner and slave, in an outward respect, may be free in Christ, free indeed; while he who enjoys full external liberty, may, in regard to his inward man, be under the power of wicked spirits: These enter and dwell in an heart garnished to receive them. Jesus Christ, and no other, saveth from sin and wrath. The spirit of life quickeneth those who are dead in trespasses, and looseth those whom Satan hath bound. ‘If we be dead with him, we believe that we shall also live with him.’

The new Jerusalem is free in a more exalted sense than the church on earth. True believers, ‘sealed with the holy Spirit of promise, have the earnest of their inheritance, until the redemption of the purchased possession.’ In that day of complete redemption, of glorious liberty, may God of his infinite mercy grant that we may meet all the ransomed of the Lord, with songs and everlasting joy, saying: “Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto him that sitteth upon the throne; and unto the lamb who was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood, out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation. Amen.”

Worth noting, Dana was far from the only one who argued this line. In a 1770 sermon (see earlier link in this series), Samuel Cooke pled similarly:

I trust on this occasion I may without offence plead the cause of our African slaves, and humbly propose the pursuit of some effectual measures at least to prevent the future importation of them. Difficulties insuperable, I apprehend, prevent an adequate remedy for what is past. Let the time past more than suffice wherein we, the patrons of liberty, have dishonored the Christian name, and degraded human nature nearly to a level with the beasts that perish. Ethiopia has long stretched out her hands to us. Let not sordid greed, acquired by the merchandise of slaves and the souls of men, harden our hearts against her piteous moans. When God ariseth, and when he visiteth, what shall we answer? May it be the glory of this province, of this respectable General Assembly, and, we could wish, of this session, to lead in the cause of the oppressed. This will avert the impending vengeance of Heaven, procure you the blessing of multitudes of your fellow men ready to perish, be highly approved by our common father, who is no respecter of persons, and, we trust, an example which would excite the highest attention of our sister colonies. (Election Sermons, 2012, pp. 226-227)

This sermon may be found online at: http://consource.org/document/the-african-slave-trade-by-james-dana-1790-9-9/, and in hard copy in Ellis Sandoz, Political Sermons of the American Founding Era (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1998).

— Dr. David W. Hall is pastor of Midway Presbyterian Church, Powder Springs, Georgia, and author of over 20 books on theology and church history.