The East-West Philosophers Conference

By NEAL W. KLAUSNER

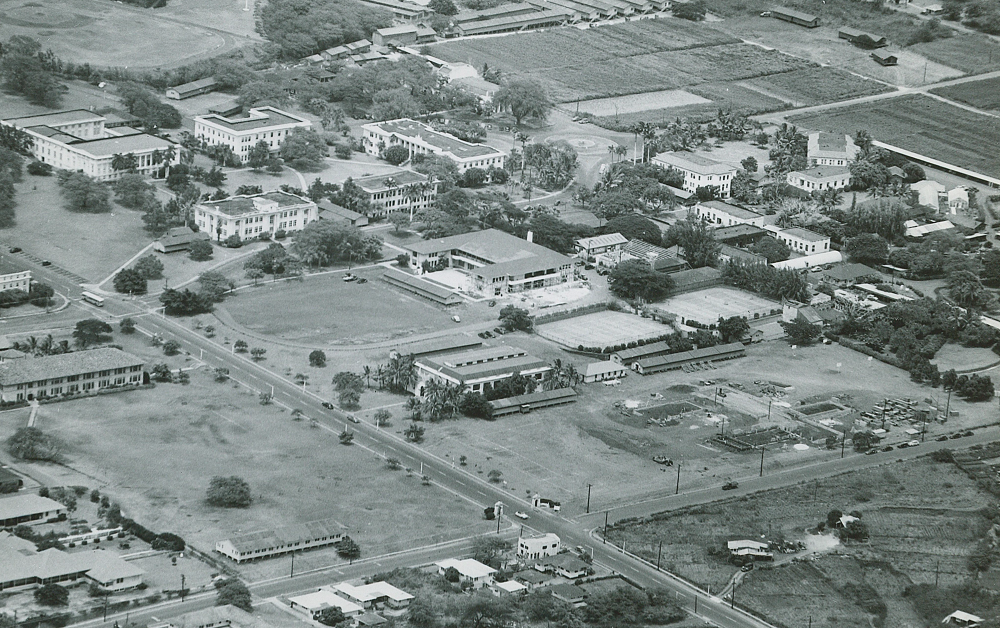

Held at the University of Hawaii during the Summer of 1949

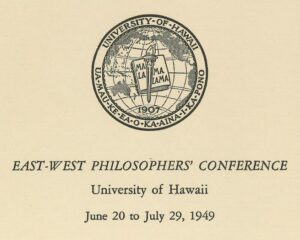

A MEETING of no minor significance took place on the campus of the University of Hawaii from June 20 to July 29, 1949.

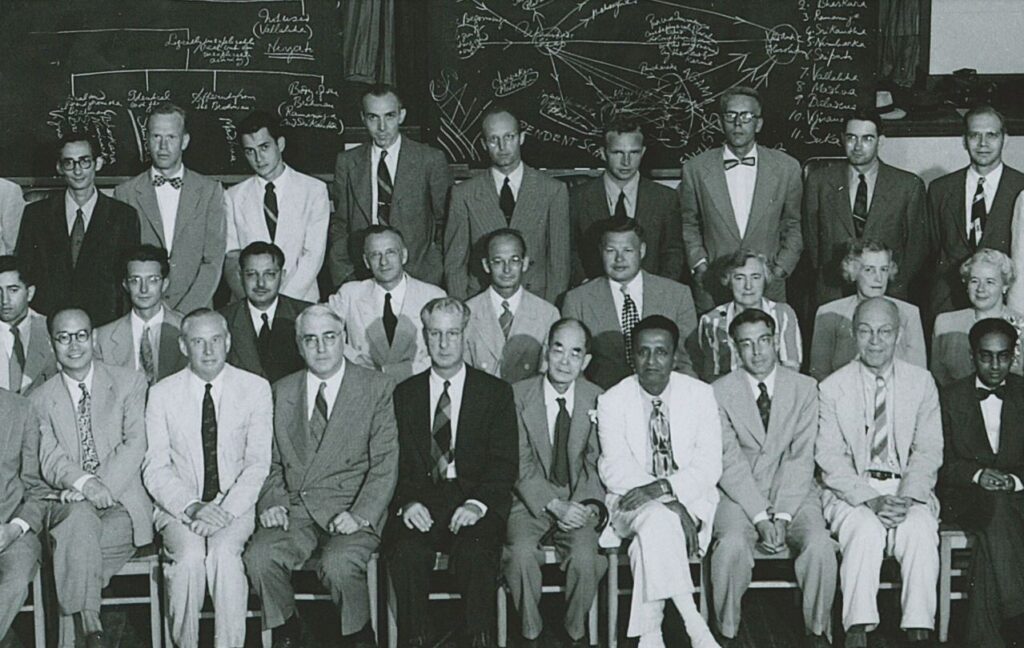

Nearly fifty philosophers from six different countries came together for six weeks to “study the possibility of a world philosophy through a synthesis of the ideas and ideals of the East and the West.” This was the second conference, held ten years after the first. The project was conceived by the distinguished President of the University and made practically possible with aid from the Rockefeller, McInerny, and Watamull foundations.

The first conference in 1939 was on a much smaller scale but was so encouraging in its consequences that a more elaborate one was planned and carried through in 1949. Three important books came out of the first meeting: The Meeting of East and West, by F. S. C. Northrop; Philosophy East and West, edited by Charles Moore; and The Essentials of Buddhism, by Takakasu.

An unusual feature of the 1949 conference was the presence of twenty-four “younger” teachers of philosophy from the colleges and universities of the United States. I put younger in quotes because some of these “associates” were older than some 87 of the ‘“‘members.” Most of the associates were able to come because of grants-in-aid made available by the foundations. The distinction between “associate” and “member” should perhaps be made clear. The members were those who came to read papers and to teach as well as to learn. The associates came primarily to learn. It was not long, however, before the distinction was forgotten. Except for reading papers, the associates were given the opportunity to participate fully and freely in the work and the discussions.

The meeting was held coincident with the summer-school session of the university. This had two advantages. It brought many more students, professors, and visitors into contact and acquaintance with the aims and work of the conference, and it also provided an opportunity for summer-school students to select a course or two from a rich offering in comparative philosophy. For example, the following courses were open to associates, members, and some of the students regularly enrolled: Indian Philosophy, Chinese Philosophy, Buddhist Philosophy, Metaphysics, Seminar in Comparative Metaphysics, Seminar in Comparative Methodology, Seminar in Comparative Ethics and Social Philosophy. Most of the associates, recognizing that such an opportunity does not often appear, enrolled in three, four, or five of these courses, and thus loaded themselves with a real burden of work. This meant that the morning from 8:30 until 12:45 was spent in class sessions.

The afternoons were free for work in the library, group discussions, recreation, trips to various points of interest on the island, and so on. In the evenings and on Saturday morning the conference program of the reading and discussion of formal technical papers was scheduled. These were extraordinarily well attended by visitors and students. In fact, many of us were completely surprised and not a little bewildered by the interest the people showed in philosophy. It was, I think, encouraging to all of us. I remember one night when Mr. Northrop, in a brilliant lecture, held the absorbed attention of a packed auditorium for an hour and three-quarters.

Near the close of the conference we were told that some of the Oriental philosophers were so impressed with the need for such meetings and the opportunities they offered that they hoped to arrange similar gatherings at the five-year interval between the regularly planned meetings of the East-West Conference, to take place in Japan or India. The President of the University also announced that the university was exploring the possibilities of having East-West conferences not only in philosophy but in the arts, drama, sociology, and so on, thus carrying out in ever-widening relations the original idea of finding ways for the East and the West to share their rich heritages, and by mutual criticism and understanding come to a community of minds. Another practical step was taken when the group gave its approval to the establishment of a journal in comparative philosophy. No name was selected for the publication, but a committee was appointed to work out the details, It is believed that the journal will perform a major service to philosophers in this country by making available articles and translations of materials not otherwise accessible.

IT IS, of course, impossible in this brief statement to give a summary of all of the papers and discussions. There were twenty-two papers read, excluding the lectures and discussions not so formally presented. Moreover, one cannot measure the great personal values that came to each of us as we participated in innumerable arguments and inquiries wherever and whenever we met, after sessions, at meals, on the beach, in the classroom, and in our rooms. It was an unusual experience and a rare privilege to live in such informal, intimate fashion with fifty men and women in one’s own field. Names which we knew only as signatures at the end of a paper or as listed in college catalogues became attached to personalities, and these soon became friends. We were all greatly disappointed not to be able to add to our growing friendships the names of Mr. Radhakrishnan and Mr. Dasgupta. The former was unable to come because of his recent appointment as ambassador to the Soviet Union, and the latter had become ill. Hu Shih, too, was expected, but affairs in China prevented his return.

Many of us came to the conference with little or no knowledge or appreciation of Eastern philosophy. When we left we not only had a good deal more information and understanding, but we had discarded many of our misconceptions. We had learned to recognize our common interests and had become aware of astonishing parallels in our intellectual history. We also learned that we can admire and respect our differences. I am sure few of us will again speak or write carelessly about “Oriental” philosophy as if it were all of one piece. Real and significant distinctions must be made not only as respects the thought of China, Japan, and India, but also concerning the variety of viewpoints and positions, as complex as the strains in Western thought, which exist within each culture. No one expected that from our similarities and differences a “world philosophy” could be derived, all pat and parcelled, ready for distribution to the peoples of the earth. I remember so vividly the first night the conference was in session when each of the members expressed his anticipations and hopes for the work to be done. No wild, absurd claims were made—no impossible goals were set up. Yet each spoke sincerely and briefly, recognizing that first steps were being taken in an enterprise that had enormous potentialities and might have as momentous consequences.

“The Seminar in Comparative Metaphysics found “three rather clearcut differences of metaphysical outlook” emerging from the discussions”

During the last day of the sessions each of the seminars brought to the conference a report of the work which had been accomplished. I cannot reproduce here those summaries, but perhaps a brief statement will give some idea of their content. The Seminar in Comparative Metaphysics found “three rather clearcut differences of metaphysical outlook” emerging from the discussions.

First of all, Hindu and Buddhist philosophy have focussed so much attention on an ultimate reality, largely inaccessible to the categories of ordinary logical discourse, that the field of finite existence has been to some extent neglected, and in some cases denied any independent, metaphysical status. This has been opposed to a prevailing Chinese and Western tendency to emphasize the independent status of nature and the individual. Second, Chinese Neo-Confucianism and Western Naturalism have generally found little need for the recognition of any absolute or self-sufficient being transcending nature. This has been opposed to important trends of Hindu and Western thought which have stressed arguments requiring the recognition and postulation of such a necessary being. Finally, in the third place, it seems to be true that Eastern thought has rarely insisted on such a sharp distinction of the purely theoretical modes of investigation from the practical as has that of the West.

“metaphysical issues indicate not only that the conflicts which have often been thought to divide Eastern and Western theories of reality are not irreconcilable, but that their resolution may have positive and fruitful consequences for contemporary life and thought.”

Then follows a statement of the major differences and basic metaphysical similarities which exist between East and West. The report concludes with an expression of the conviction that the conclusions actually obtained concerning basic, metaphysical issues indicate not only that the conflicts which have often been thought to divide Eastern and Western theories of reality are not irreconcilable, but that their resolution may have positive and fruitful consequences for contemporary life and thought.

“It also seems to be generally agreed that they should be analyzed on the supposition that East and West can be found in the main to complement rather than to contradict each other’s methodologies, but that points of possible conflict should be frankly faced.”

The report of the Seminar in Methodology, after presenting what had been discussed as the major differences in the methodological assumptions between East and West, stated that the general consensus seems to be that there is something in each of these suggested contrasts if they are not pressed too far or regarded as more than dominant tendencies. It also seems to be generally agreed that they should be analyzed on the supposition that East and West can be found in the main to complement rather than to contradict each other’s methodologies, but that points of possible conflict should be frankly faced.

The report of the Seminar in Comparative Ethics and Social Philosophy contains the statement that no basic and consistent East-West cleavage was discovered in moral doctrine and ethical theory. Differences in emphasis and in the ordering or ranking of values were often evident.

It must not be thought that these reports represent final conclusions accepted by everyone. They are simply summaries of the work done and include the areas of disagreement as well as agreement. Each report was read and subjected to further scrutiny before a general session.

I cannot close this account without remarking on the hospitality and generosity of the University of Hawaii, its administrative officers, secretaries, and teaching staff. Everyone seemed eager to be friendly and to make our work successful and our visit pleasant. There was a sincerity and genuineness about our welcome that never wavered even when taking care of us must have cost a good deal in labor and patience. The geographical appropriateness of the university for an East-West conference is matched by its magnificent spirit and complete willingness to do everything to make a real meeting of minds possible.