The following was originally published in ‘The Dawn Horse’ magazine, No 3, January 1976 by the ‘The Dawn Horse Communion’.

Whenever there is a decline of righteousness and rise of righteousness, O Bharata (Arjuna), then I send forth (create incarnate) Myself.

For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the wicked and for the establishment of righteousness, I come into being from age to age.1

Gu-ru: Darkness—Light, the Light that dispels darkness, the Truth that dispels ignorance, the Divine Reality that gracefully assumes human form to awaken men to Itself. As Lord Krishna said in The Bhagavadgita, the Guru comes again and again to reestablish the Dharma, the Way of Truth, among human beings.

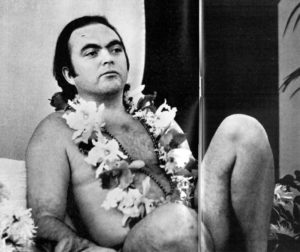

In this article we trace the appearance of the Guru throughout recorded human history and examine the expression and elaboration of the Dharma or Teaching of Truth in many cultures over time. Then, on the basis of this historical overview, we consider the implications for men today of the appearance, Teaching, and Presence of Bubba Free John.

Bubba speaks of genuine Gurus as “Siddhas”:

There are many kinds of Siddhas. siddha just means, in common language, somebody who has accomplished or realized some extraordinary function, a siddhi of some sort. Many, by virtue of evolving subtle capacities, pass into cosmic dimensions that are extraordinary. Such beings can be called siddhas, and such worlds could be called siddha-worlds. But the true Siddha is the God-realized Siddha, completed, fallen into the prior and perfect condition. And the true world of the Siddhas is simply the Divine Reality, the Divine World, which cannot be described. That world truly is the God-world. Even what is called a Siddha Loka within the traditional literature is still a conditional world, a dimension within the reflected cosmos.

Thus the true Siddha is One who comes out of the God-Light, out of the God-world, not just one who emerges from some extraordinary state into a human birth with various powers or capabilities. The true Siddha is one who lives in the God condition, while alive in the manifest worlds. He is not extraordinary. He is living, simply living, the appropriate form of life: He is living the appropriate or natural state. He appears extraordinary only over against those who are living from the point of view of karma, limitation, ignorance. But his assumption is that there is only Truth already, that there is only God already, that there is no world and no change of state to be sought as if they were the Truth. But in this instant, whatever the apparent condition, Truth is the condition, God is the condition.

One who moves into relationship with such a Siddha has come face to face with Real-God and the God-Light. The Siddha, the Heaven-Bom One, manifests the heaven condition to his devotee. Thus the devotee of such a Siddha lives the heaven condition while alive, whatever condition he may apparently be living. The Siddha brings the heaven condition into the world and lives it and makes it entirely available to those who will turn to Him, or Her. Such a One does not create the heaven appearance. In other words, he does not perform magic and make this world seem like the God-world. This world remains what it is, what its appropriate, lawful appearance is. Perhaps he expands the range of some of its faculties, but essentially it remains what it is, what it latently is. It is just that the God condition becomes also the condition of the world in which the Siddha is appearing. This is the purpose of such Siddhas, to appear in the conditional worlds and live the real condition in those worlds for those who turn to them.2

From the dawn of human time men have responded most readily to the Divine in the form of a man— a human being—coming as one of their own. Of these ancient great Ones we have only myths and legends. Were they real men? Were they Siddhas? Mithra, the savior of Persia. Hermes Trismegistus, of legendary Atlantis and ancient Egypt. Quetzalcoatl of the Olmec culture in America.

And then the possible Siddhas of whom we have more specific and personal records, even if some of these also are mostly legends passed down for generations by word of mouth: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the fathers of the Hebrews, a desert tribe devoted to the worship of the One God. Akn-aten, the Pharaoh who single-handedly tried to force Egypt to discard two thousand years of animism, pantheism, and obsession with death, by worshipping the Divine Sun, the Aton, transcendental Source and life-giving Light of all beings. Moses, the great lawgiver of the Hebrews who delivered them from slavery in Egypt. Lao-tzu, the sage of China, who taught unmotivated adherence to the eternal Tao, the Divine Principle, in the midst of a simple, ordinary life.

In every culture we have accounts of such great individuals, and these legends form the foundation of what Bubba Free John has called the “Great Tradition” of esoteric spirituality among men. At the head of each specific tradition stands an individual, a Siddha-Guru, the seed of a new and specific aspect of the Divine Work in this world. Human life has been a long history of reaction to the condition of manifest existence itself, in other words, of vital shock—a history of assumed limitation, suffering, and seeking for fulfillment, transcendence, or release. And all the spiritual teachings brought by the Siddhas have in one way or another spoken to that dilemma, assumed its reality, and allowed men to proceed on its basis, even while the Divine influence of the Siddhas themselves moved to undermine that whole life of difficulty and search.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the teachings that have arisen in the motherland of human spirituality, India. The different traditions that have appeared over time in India are almost, literally, innumerable. But for the purpose of picking up the main threads of the Great Tradition, we can isolate two distinct paths, each with its own specific assumptions about the character of man’s dilemma, its own processes of seeking to undo it, and its own centers in the human psycho-physical mechanism of gnosis or Divine knowledge. The first of these paths is the way taught by Gautama the Buddha, and the second is that taught by Krishna the Avatar.

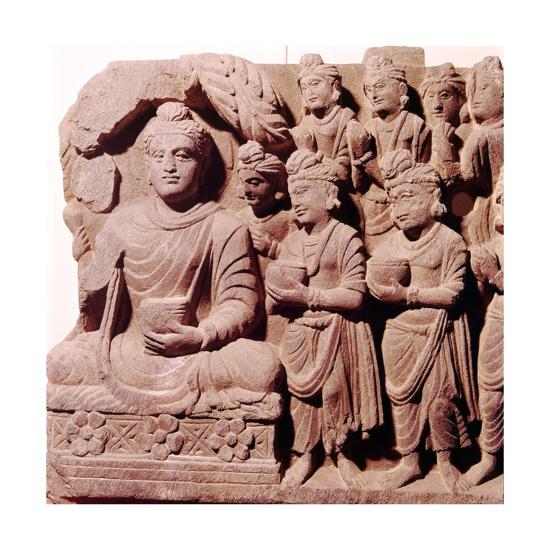

Gautama was born the son of a king in northern India some 2500 years ago. Even into his early manhood Gautama had no knowledge of the hardship and death that life inevitably entails. But then he became aware of all this, and it profoundly disturbed him. Immediately he abandoned his home, family, wealth, and the throne to which he was heir and went out as a mendicant to seek the Truth that releases man from a destiny of sorrow. For several years he tried the spiritual “methods” available in his day, mainly extreme yogic techniques and asceticism. He learned much about the processes of mind and life itself, but he did not realize Truth. Still suffering, he saw that all his extremes had only succeeded in weakening him to the point of death. He renounced them, regained his strength and clarity—and only then, as legend has it, did he attain the Nirvana or “Great Quenching” that is at the center of his teaching. For the next forty years he wandered throughout India, criticizing the false paths of the time, teaching the way of release from suffering, and attracting thousands of others to become his monks and students, live their lives in the practical and specific ways he demanded, and enjoy that same liberation through the influence of Satsang with him.

Gautama expressed the essence of his teaching in a few precepts that have come to be called the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism:

1) All life is suffering.

2) The cause of suffering is ignorant desire.

3) The extinction of suffering can be achieved.

4) There is a path that leads to the extinction of suffering: The Eightfold Middle Way.

Bubba refers here to the purest representation of the teaching that Gautama himself actually delivered to disciples. Like all the major esoteric traditions, Buddhism over time has come to incorporate streams of the teaching found in many other spiritual sources. But the Buddha himself taught specifically a way of release or escape from the principle of life altogether through the sacrifice of desire.

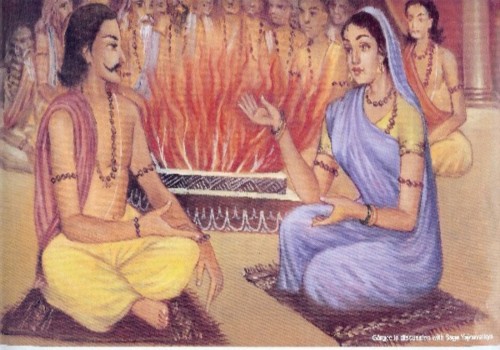

The second of the most historically important Gurus who appeared in ancient India was Krishna the Avatar, who reputedly lived some 2000 years before Gautama. We have no certain historical record of him, but the legends of his life are full of miracles, captivating tales of Divine love and play with devotees, and some of the most sublime teachings known to man. Krishna, we are told, was an intensely beautiful man with an unusual blue luster to his skin; a prankster who, as a child, revealed all the manifest and unmanifest worlds to his mother when she looked in his mouth for stolen butter; an amazingly precocious disciple who soon far exceeded the realizations of his teachers and was recognized as an Incarnation of God; a Divine lover who enchanted literally thousands of women, many of them the young milkmaids known as gopis; and a charioteer for his disciple, the warrior Arjuna, in the famous clash that is the setting for The Bhagavadgita or “Song of God.”

Krishna was the Great Siddha of the sahasrar or the subtle epitome, the subtle region above the head. He taught and demonstrated the dharma of the sacrifice of the mind, the merging of the mind in God.4

This, primarily, is what Krishna has represented historically: the dharma of the Divine Light, God above, and the process of absorption of the mind in this Condition through concentrating in the subtle regions. A whole array of traditions relates directly to this teaching, including mantra yoga and the devotional chanting or thinking of Divine Names, and focusing attention on the Sound Current and lights and forms above the thinking mind. All of these are ways of abandoning vital life and seeking the subtlemost Divinity:

He who utters the single syllable Om, which is Brahman, remembering Me as he departs, giving up his body, he goes to the highest goal.

He who does so, at the time of his departure, with a steady mind, devotion, and strength of yoga and setting well his life-force in the centre of the eyebrows, he attains to this Supreme Divine Person.5

But, just as with Gautama, we find in Krishna’s words evidence of his own transcendence of the particular forms and limitations of his path, and some of the world’s most profound confessions of fully Divine life.

I, O Gudakesa (Arjuna), am the self seated in the hearts of all creatures. I am the beginning, the middle and the very end of beings.6

All the gates of the body restrained, the mind confined within the Heart, one’s life force fixed in the head, established in concentration by yoga.7

To these who are constantly devoted and worship Me with love, I grant the concentration of understanding by which they come unto Me.

Out of compassion for those same ones, remaining within My own true state, I destroy the darkness born of ignorance by the shining lamp of wisdom.8

The Lord abides in the hearts of all beings, O Arjuna, causing them to turn round by His power as if they were mounted on a machine.

Flee unto Him for shelter with all thy being, O Bharata (Arjuna). By, His grace shalt thou obtain supreme peace and eternal abode.9

The third of the most important Siddha-Gurus who have appeared among men lived almost 2000 years ago in what is now Israel: Jesus the Christ. Most of us in the West are quite familiar with the story of Jesus’s life: the legends of his birth; the story of his childhood disputations with rabbis in the temple; the missing years of adolescence and early manhood when, some say, he traveled in the East and did sadhana there; his baptism by John the Baptist and the assumption of his mission among men; the three years of his traveling, healing, and teaching simple folk, prophesying against the Godless, established priesthood of his time, and, finally, being crucified; and the chronicles of his band of disciples as they tried to carry on his work.

Jesus was the Great Siddha of the region of the heart. Just as the mind has its seat in the upper regions of the head, and desire has its seat in the great vital region of the navel, the ego or separate self and its dissolution are seated in the heart. Jesus taught and demonstrated the dharma of the self-sacrifice, the dharma of the surrender of the ego in life terms, in functional and human terms. And so the dharma of the sacrifice of the self is the dharma of the heart.10

In other words, historically Jesus represents not a mystical path so much as a way of concrete sacrifice in action, in life itself. This should be clear to anyone who listens to Jesus’s fundamentally moral and practical instructions, or who examines the absolute life-level demands and the “ass-kicking” he gave his devotees.

Bubba has also spoken about Jesus’s real spiritual work with devotees:

He served the Dharma in the world from a distinct point of view. Jesus is full of talk about the father, though in the little that is reported in the New Testament he never says he is God in some exclusive sense. He is talking about his oneness with the Father. Always the Father is the great one. The Father is simply a word in his tradition for the ultimate, Absolute, and Unqualified Reality, the Heart. Jesus was intuitively aware of the Heart and we can assume that it was fundamental to his realization. But his activity, his teaching work, was of another kind. It was an activity within the cults of his time to purify them.

A major aspect of his work was his baptizing work. John the Baptist was always talking about Jesus as somebody who would do what he was doing, but on a higher level. John baptized people to cause them to turn away from their life of sinning and to believe in the Divine. But Jesus was to be the Divine agent in the world and to baptize with the Light itself. Therefore, Jesus performed a baptizing work like John the Baptist, except that he baptized people with fire, with energy, and caused them to have hallucinations through which he would guide them. There was a Siddhi, an energy Siddhi, a Light-oriented Siddhi, operating in him, and that Siddhi is the limitation of his work. The communication of that Siddhi was his orientation, his function. Clearly that communication is a dimension of his teaching. And in so far as he has served the great transmission of the Dharma through time, it is that communication, that aspect of his work that has been emphasized.

Truly he was a great spiritual figure, a Siddha, because of his own transcendence of the doctrine of Light. He did not make the Light the center. He did not make himself the center, as a symbol of the Light. He always spoke of the Father and so he functioned as a Siddha, that is, one who transcended the limitations of his own function, while at the same time perfectly fulfilling his function at the level of his life and teaching.11

I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life: no man cometh to the Father except through me.

I and my Father are One.

Yet a little while is the Light with you. Walk while you have the Light, lest darkness come upon you: for he that walkest in darkness knoweth not whither he goeth.12

While you still have the Light, believe in the Light, and you will become the sons of Light.13

I call Jesus, Krishna, and Gautama Great Siddhas because they so uniquely and with such historical force represented the dharmas that pertain to the fundamental conditions of suffering. . . . The three Great Siddhas have represented to mankind the three principal dharmas as they have been understood to this time. Jesus represented the dharma of the sacrifice of self, Krishna the dharma of the sacrifice of mind, and Gautama the dharma of the sacrifice of desire. Separated self (or ego), limited mind, and limiting desire are the three principal conditions of suffering or contraction in man. Thus, the three principal dharmas that have been known among men have been attempts to undo these forms of contraction through the deliberate or motivated sacrifice of these three: ego, mind, and desire.14

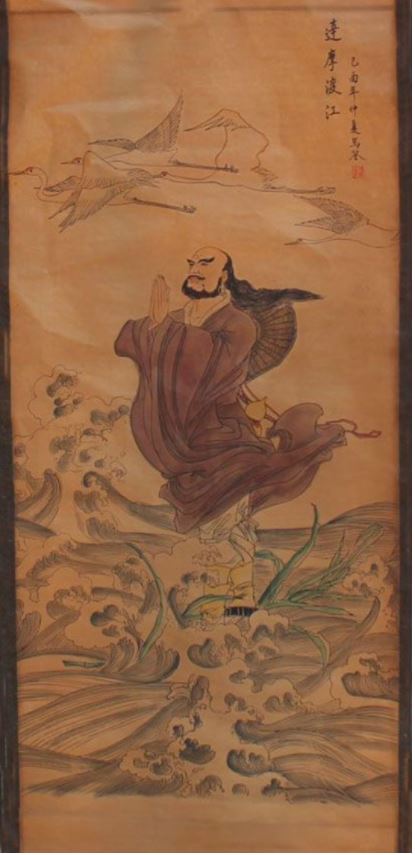

If we were to examine every genuine esoteric tradition of mankind, we would find that the communications even of the real Gurus who appeared among them, or who founded them, reflect in one form or another these principal dharmas represented by Gautama, Krishna, and Jesus. And yet the Siddhas have all been humorous and radically free men, men who lived beyond the limitations of the teachings and practices they communicated, men who truly taught through the influence of Satsang itself. Some of the most important and colorful of these agents of the Divine who have lived since the days of the three Great Siddhas have been: Bodhidharma, the 28th patriarch of Buddhism in India, who traveled to China around 527 A.D. He established Buddhism as an integral part of Chinese culture and was the first Patriarch of the Chinese Ch’an sect, which became known in Japan as Zen. Legend has it that one seeker, desperate because Bodhidharma refused to instruct him, cut off his left arm and presented it to Bodhidharma. The ensuing brief interrogation, with Bodhidharma completely unperturbed by the man’s self-mutilation, led to the man’s sudden awakening— thus the beginning of the Zen “koan” tradition.

A special transmission outside the scriptures;

No dependence upon words and letters;

Direct pointing at the soul of man;

Seeing into one’s nature and the attainment of Buddhahood.15

Hui Neng was famous for being completely illiterate—thus, as you see, his enthusiasm for the Buddhist scriptures.

When Bodhidharma came to China, he said:

My aim in coming to this country

Was to transmit the Dharma and liberate all beings.

A flower of five petals

Cannot fail to fruit.16

Hui Neng was the “fifth petal”—the sixth Patriarch, counting Bodhidharma—and the last of the lineage of Patriarchs. In honor of his cultured ways he was called “The Barbarian.” When he first arrived at the community of his Guru, the fifth Patriarch, he was given the roughest possible work away from the others—but the Guru later explained that this was to keep him unspoiled by their confusion. But Hui Neng’s Altar Sutra (which he dictated to a disciple) is one of the greatest of the Buddhist texts in any tradition.

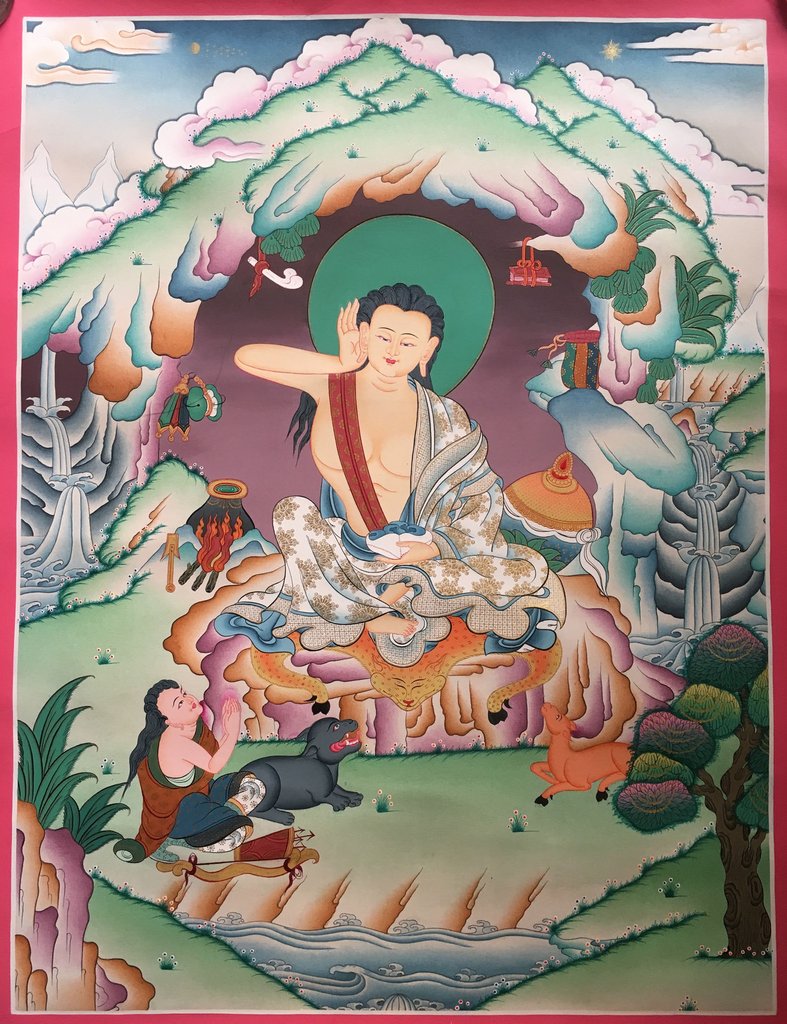

Milarepa, the famous 11th century yogi and poet of Tibet, performed one of the most arduous and dangerous paths of sadhana that has ever been recorded. Starting his spiritual life as a “black magician,” Milarepa was required to build and then tear down one stone house after another, one boulder at a time, before his Guru, Marpa the Translator, would even consent to initiate him into tantric practices and meditation. But eventually Milarepa rose to full realization and carried on Marpa’s work as Guru himself.

Lord, from the sun-orb of Thy Grace,

The radiant Rays of Light have shone,

And opened wide the petals of the Lotus of my Heart,

So that it breatheth forth the fragrance born of Knowledge,

For which I am ever bounden unto Thee;

So will I worship Thee by constant meditation.17

St. Francis of Assisi, who lived in Italy about a century after Milarepa’s time, was converted from his playboy ways and dreams of knighthood by an over whelming vision of Christ on the Cross. He then undertook a monastic life of the most intense poverty and self-denial. St. Francis founded an order of friars based on deliberate and literal imitation of the wandering, impoverished way of life followed by Christ and his Apostles. A devotee or bhakta at heart, St. Francis was the kind of man who could be disappointed by absorption into the Absolute because it interrupted his vision of Christ.

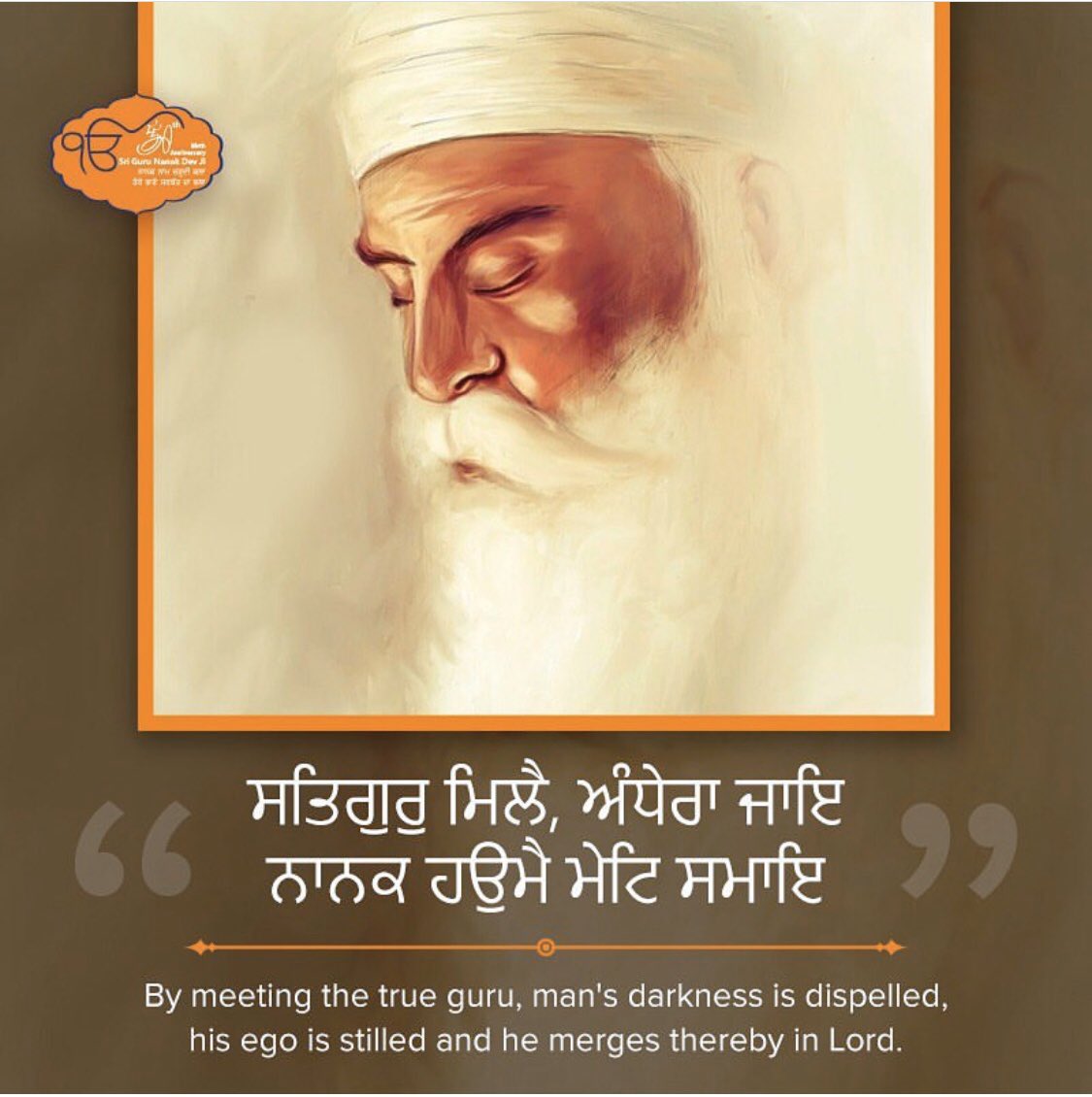

Guru Nanak, who lived around 1500 A.D., was the founder of the Sikh religion in India and the first of its ten Gurus. He taught that the Shabd or Naam, the Word or Name of God, is the most direct path to Union with God and that this Union is possible through the practice of the yoga of concentration and absorption in the internal, subtle Sound Current and above in the Divine Light.

A contemporary of Nanak’s, Kabir was a weaver from Benares and a twice- married householder who was also Guru to both Hindus and Muslims and one of the greatest mystic poets of human history. Kabir was highly critical of the life he saw around him and composed hundreds of poems criticizing the traditional modes of life and the religious ways of his time. He also wrote endless songs and hymns in praise of the Guru and God.

Remember, meditate, O my mind: thy life is passing away without God’s name. A bird without wings, an elephant without tusks; a woman husbandless; as a harlot’s fatherless son is nothing, so is the mind without God’s name.18

That Lord which even the great Brahma, Suras, munis, and gods could not find,

Though they became exhausted in the search;

That Lord is found by ordinary mortals

Through the grace of a Master.

Therefore, says Kabir, O brother seeker, Do the devotion of a Master

Who is the Lord Incarnate.19

St. John of the Cross, another Christian Saint, was born in the late 1550s in Spain. Friend and spiritual director of St. Teresa of Avila, he was often per secuted by the Inquisition, and attained his greatest realization within the con fines of prison. He is most famous for his book The Dark Night of the Soul.

On a dark night, kindled in love with yearnings—oh, happy chance! —

I went forth without being observed, My house being now at rest.

In darkness and secure, by the secret ladder, disguised—oh, happy chance! —

Oh, night that joined Beloved with lover, Lover transformed in the Beloved!

I remained, lost in oblivion; My face I reclined on the Beloved.

All ceased and I abandoned myself, Leaving my cares forgotten among the lilies.20

Tukaram was a highly humorous saint of 17th century India who composed thousands of poems denouncing all outward forms of worship.

Tukaram lived in a culture that was devotionally oriented, committed to the duality or radical separation of God and man. But he would go around telling everybody there wasn’t any God. When he sat down, he could find no One to meditate on. He claimed that he was himself God. He went on and on like this, disturbing all the orthodox devotees, until, one day, he just disappeared. He had been sitting with his disciples all night, chanting, enjoying deep meditation, when all of a sudden, there was a blast of light, and he disappeared! There have been a number of such cases of people who were reported to have abandoned their life in the world by such “absorption.” It is not a common form of “death,” even among the Siddhas. It happens rarely as a matter of fact, but Tukaram was a very humorous guy!2l

Satsang is the only “method” of real spiritual life. And it is the method of the Guru, not the devotee. There is nothing the devotee can do to realize the Divine. The Divine comes in the form of the living Guru and becomes, absorbs the devotee. Thus Satsang, that relationship, that continuous contact, is the very foundation of the work of all Siddha-Gurus. One of the characteristics of the Siddha is that he requires and seeks out devotees to live and work with. He does not offer philosophy or techniques that can be applied in isolation. He offers himself in Satsang. He must, so that the transforming conscious force or Siddhi of his presence is allowed to move and function. This is especially obvious in four of the most outstanding Gurus who have appeared in modern times, whose mature lives and teachings are well documented: Bhagavan Nityananda, Sai Baba of Shirdi, Sri Ramakrishna, and Sri Ramana Maharshi. Like the Great Siddhas of the past, these individuals are significant because they were specific agents of the three principal dharmas of the past who also transcended these dharmas in their lives and full teachings. And these men also played crucial roles in the sadhana and realization of Bubba Free John.

Bhagavan Nityananda was a Yogi-Siddha who lived most of his adult life in Ganeshpuri, India, where his Ashram still stands today.We have no record of his early life. Legend has it that even as a child he shaved his head and wore the ochre robes of a sannyasin or renunciate. He reportedly spent about six years in the Himalayas, and first revealed himself as a Siddha in South India, living most of the time in a mountain cave in deep samadhi and giving darshan to devotees in a large Ashram that he built near the town of Kanhangad, not far from the sea. Nityananda used to travel on foot all over the surrounding areas as an avadhoot, a God-realized sadhu or renunciate.

The later period of his life, which he spent at Ganeshpuri, not far from Bombay, was the time when most of his devotees came to him. Nityananda spoke little and gave few instructions. If anything, he would give them a mantra to remember him by, but fundamentally his work was silent: to give darshan and directly transmit to others the Divine Fullness that he himself enjoyed. Nityananda died in 1961.

True yogis are living, forceful beings. They are madmen, absolutely mad—and absolutely dangerous. The Lord is of that kind. Therefore you should not approach me if you are not willing to be undone. Look at Nityananda. He severed heads all his life. Look at his belly. He was stiff with life, full of life, so his belly became huge with that force. And those who came to him just wanted to bow down and worship in the nominal way. He allowed them to do that, of course. But those who came to him in the true way were wiped out—torn apart!22

Bhagavan Nityananda functioned primarily as a Yogi-Siddha, and his spiritual force could be felt in the navel center as a force that purified vital or gross life, the field of desire. So there were all sorts of yogic energies and miracles associated with his work. But Nityananda himself enjoyed the full realization of Divine Life. His teaching accounted for the yogic process but also pointed beyond to Self-realization and Transcendent Knowledge:

Even though the various mantras are different, the same chaitanya shakti pervades them. The all-inclusive Divine force pervades all mantras equally and bears the same fruit.

Be calm; I am everywhere. All this is my manifestation.23

The lamp is Self-knowledge; the Light is of Kundalini.

Siva is not realized by the mind. Karma is not done by the hands, neither by legs. O mind, act with desirelessness. Attain desirelessness and regard all.24

Shirdi Sai Baba’s early life is also clouded in myth and legend—we only know that he appeared in 1856, a young man of sixteen or so, in a wedding party in the village of Shirdi in India. Even then the Guru-function was fully alive in him. Sai Baba’s life also was full of miracles, and yogic processes manifested spontaneously in his Presence. But like any other Siddha, Baba neither sought his powers nor desired to merely fascinate people. He used these and all the other paradoxical and dramatic events he created to turn people to him as Guru in Truth.

Shirdi Sai Baba’s function as Guru was basically that of a Saint, one who purifies the subtle vehicles of devotees and leads them to enjoy the subtle dimensions through sacrificing the mind to the Divine Light above body, mind, and world. But Sai Baba fully transcended that function in his own realization. His verbal teaching did not limit devotees to the traditional machine of seeking, though he did in some cases allow his devotees to pursue their sadhana from the point of view of the search. Baba was as likely to point to Self-realization through

a form of self-enquiry, as he was to recommend the chanting of God’s name and the surrender of mind. But most often Shirdi Sai Baba simply invited devotees to enjoy Satsang directly.

If one perpetually thinks of me and makes me his sole refuge, I become his debtor and will give my head to save him.

I am God. I speak the Truth sitting as I do in the mosque. I am the absolute attributeless Nirguna. I have no name and no residence. I fill all space and am omnipresent. I am the Progenitor of God.

I am the bond slave of my devotee. I love devotion. He who withdraws his heart from the world and loves me is my true lover and he merges in me like a river in the sea.

Trust in the Guru fully. This is the only sadhana. Guru is all the Gods. 25

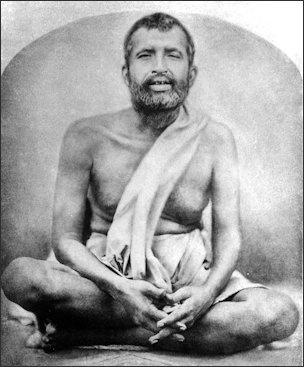

Of these four modern Siddha-Gurus, Sri Ramakrishna is perhaps the best known in the West. Born in a Bengali village in the early 19th century, he demonstrated even as a child a profoundly spiritual nature and was never drawn to anything other than sadhana and Divine Realization. Ramakrishna’s own sadhana is legendary because of his willingness to do anything, however bizarre, to serve his realization of Truth and his devotion to God in the form of Kali, the Shakti or Divine Mother, a Hindu representation of the God-Light. At various times in his life he climbed through trees and hooted like a monkey; went into samadhis for days at a time; dressed in woman’s clothing and lived among women for many months; wept and wailed for lack of the Divine Vision, and nearly killed himself because the Mother had not revealed herself to him. Before his own true devotees arrived, those to whom he could fully manifest his spiritual force, Ramakrishna used to pace the rooftops at night, weeping and wailing “like a cat in heat,” he said, waiting for them; and once the young men who were to be his chief disciples arrived, he rejoiced in them like a child.

One of Ramakrishna’s main functions as a Siddha was to demonstrate the fundamental universality of religions by realizing the goals of each, but throughout his life, long after his own sadhana was done, he played the role of the devotee, and constantly went into devotional trances. By his own testimony, however, these trances were not of a subtle nature, but amounted to direct in tuition of the Absolute Reality. While he taught a fundamentally dualistic sadhana of absorption of the mind in God, he realized and also pointed in his teaching to the non-dualistic, transcendent Divine Nature.

The more a man approaches the Universal Being, the newer and greater become the revelations of His infinite nature, and in the end he merges in Him through the consummation of knowledge.

Jnana is the realization of the Atman [the Self] by the elimination of all phenomena. . . . And Vijnana means knowing with greater fullness. . . . After attaining Vijnana a man can live in the world as well. For then he clearly perceives that He Himself has become the world of living and non-living substances, that He is not outside the world.26

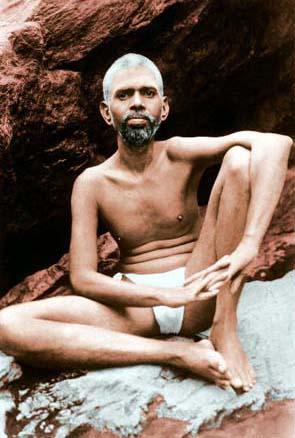

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi lived in South India during the first half of this century. Maharshi was a relatively ordinary boy until, at the age of seventeen, he was overwhelmed by the fear of death and spontaneously enquired of himself, “Who am I?”—and thus perfectly realized the Absolute Self-Nature, in less than half an hour. He shortly left home and lived the rest of his life at the mountain Arunachala, to him the embodiment of the Divine. An Ashram grew up around him there, and he consented to perform the Guru-function for devotees.

While Nityananda was a Yogi-Siddha whose force worked in the navel, the life-vehicles, and Sai Baba and Ramakrishna were Saint-Siddhas whose force purified the mind and subtle body, Maharshi was a Sage or Jnani-Siddha whose spiritual presence was the force of the Absolute Heart. Maharshi worked specifically to undermine the ego, the “I” or separate self sense of devotees. Yet, as Bubba has said, Maharshi fully enjoyed Perfect Divine Realization, which transcended the limitations of the specific path of Self-knowledge that he taught, and embraced the enjoyment of both Yogis and Saints as well.

This poem about the fully Divine Life was written to the mountain Arunachala, which he considered his own Guru:

O Arunachala! in Thee the picture of the universe is formed, has its stay, and is dissolved; this is the sublime Truth. Thou art the Inner Self, Who dancest in the Heart as “I.” “Heart” is Thy name, Oh Lord!

He who turns inward with untroubled mind to search where the consciousness of “I” arises, realizes the Self, and rests in Thee, O Arunachala! like a river when it joins the ocean.

Abandoning the outer world, with mind and breath controlled, to meditate on Thee within, the Yogi sees Thy Light, O Arunachala! and finds his delight in Thee.

He who dedicates his mind to Thee and, seeing Thee, always beholds the universe as Thy figure, he who at all times glorifies Thee and Loves Thee as none other than the Self, he is the master without rival, being one with Thee, Oh Arunachala! and lost in Thy Bliss.27

All these four Siddhas, as well as other teachers, human and non-human, served in one way or another the sadhana and realization of Bubba Free John. And Bubba has said that after his personal sadhana was finished, and there was nothing left to be done, no vestige of separative existence to be undone, then the Guru-function became active in him. The Guru-function is not identical to radical understanding; it is a specific function that may arise in the case of one who enjoys that Condition. But it requires no outside validation, no external credentials. It is the self-validating function of the very Divine as Awakener, That which leads men from darkness to Light: Guru.

Yet the Teaching of Bubba Free John itself is sufficient testimony to the Condition he enjoys and has come to make available to devotees, as anyone who truly listens to his criticism of the dharmas of the past must surely recognize:

The three principal dharmas are themselves forms of seeking, reactions to the fundamental dilemma which motivates the usual man. The three Great Siddhas, along with all the other Siddhas, and all the yogis, saints, sages, and prophets, and all the men of experience, including the whole range of human individuals, themselves represent a limitation, a form of seeking founded in dilemma. The principle of the search remains intact in the great work of all the Siddhas to now. And the effort of all the dharmas, including the three great traditional dharmas, has been to strategically overcome separate self, limited mind, and the force of limiting desire.

My own work is not separate from the great work of the Siddhas and Great Siddhas, but my work is a new performance of the dharma of the Maha-Siddha, and represents a new teaching from a new point of view. .

The separate self, limited mind, and force of limiting desire are all expressions of this principal contraction, the avoidance of relationship. So if this principal contraction is undone in the process of understanding in living relationship with the Man of Understanding, then the force of the three common principles is already undermined.

The three centers, the navel, the head, and the heart, are, properly, the seats of the inclusive intuition of the Divine in man. But they are realized in Truth only in the spontaneous, already selfless revelation of Satsang. Those who concentrate upon them wilfully and exclusively with sophisticated techniques, as if to find God at last, are like Narcissus. They only meditate upon their own reflections in waters that lie on holy ground. But the Man of Understanding enjoys mastery of the ego, mind, and desire without exclusion. He enjoys Realization of Self, Mind, and Life, which are the World. He is Guru in the three seats of Realization, the seat of Life (the great region of the navel), the seat of Light (the ajna chakra, the sahasrar, and above), the seat of Self (the heart, on the right). He enjoys this Realized Mastery entirely apart from all dilemma and seeking, and he awakens it also in others apart from all exploitation of seeking in dilemma.

Therefore, this sadhana is new and great, and perhaps it is difficult to grasp for those who have only the traditions to which they would resort. In fact, apart from what is newly being communicated here, only the traditions of seeking can be found. But the work and the realization of the Man of Understanding are not fixed in any one of the traditional centers or dharmas or approaches. Just so, his point of view is not the point of view of the Divine qualities represented by any of the three great traditional paths and the exclusive seats of their knowing within man. His point of view is That which is prior to the three great dharmas. His point of view is the Divine itself.28

Thus it can be seen that what Bubba Free John represents to us is by no means a path of throwing away the Great Tradition that has come before or the appearance and testimony of all the Siddhas who have appeared among men. On the contrary, what Bubba represents is the Teaching of the Siddhas itself, directly, and fully, without any concession to or exploitation of the dilemma from which men have always come to the Siddhas to find release. What is available to us here today, through the appearance, Teaching, and Presence of Bubba Free John, is the non-exclusive Dharma of very Truth, the culmination and perfect fulfillment of all the dharmas that have gone before. What Bubba offers is the consuming Presence and Power of the Absolute Divine, functioning here and now, without obstruction or limitation, for the sake of devotees.

I am not the one who, having slept, awakes.

I am the one who is with you now.

I am the one who speaks from his own silence.

I am the one who always stands present in his own form.

I am the one who always and already exists, enjoying his own form as all conditions and states.

I am the one about whom there is no mystery and no deeper part.

I am the one who always appears exactly as he is.

I am the one who is always present.

I recognize myself as every thing, every one, every form, every movement.

I am always only experiencing my own bliss.

I am neither lost nor found.

Understanding is my constant intelligence.

I am the Amrita Nadi.

I manifest from the point above to every center, every body, realm and experience, between the upper and lower terminals of the worlds.

I continually sacrifice the energies below, the terminal processes of the worlds, to my Heart.

I live all things.

I never return to myself but always appear as myself.

There is no dilemma in the process of my appearance.

Those who do not abide as me, already the Heart, are always only seeking me from the place where they begin.

I am only the Heart, which is Reality.

I am only the Amrita Nadi, the Bright, which is the Form of Reality.

I always see everything within my own Form.

In every state, I exist only as my own Form.

I am the Heart, who never renounces his own Form.

I am the Heart, who contains his own Form.

Therefore, I have neither Form nor Self.

I am eternally in one place, contemplating my own bliss.

At that point of contemplation, which is bright, all things appear and are accomplished.

The Heart is that bliss point of contemplation and Presence.

The Amrita Nadi is that bright fullness wherein all things appear.

I hold up my hands.29

FOOTNOTES: The Guru

1. The Bhagavadgita, translated by S. Radhakrishnan (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1973), pp. 154-155, IV:78.

2. Bubba Free John, “The Cosmos,” a talk to the Ashram on May 29,1973.

3. Bubba Free John, Garbage and the Goddess (Lower Lake, California: The Dawn Horse Press, 1974), p. 245.

4. Ibid.

5. The Bhagavadgita, translated by S. Radhakrishnan (New York: Harper & Row, Publisher^, 1973), pp. 231-232, VIIL13, 10.

6. Ibid., p. 262, X:20.

7. Ibid., p. 231, VIII:12.

8. Ibid., p. 259, X:10-ll.

9. Ibid., p. 374-375, XVIII: 61-62.

10. Bubba Free John, Garbage and the Goddess, p. 245.

11. Bubba Free John, “Everything You Wanted to Ask about Christianity but Were Afraid to Know,” a talk to the Ashram on March 30,1975.

12. The New Testament, King James version, John 14:6; 10:30; 13:35.

13. The New Testament of the Jerusalem Bible, John 12:36.

14. Bubba Free John, Garbage and the Goddess, pp. 243-244.

15. D. T. Suzuki, Zen Buddhism (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1956), p. 61.

21

16. Lu K’uan Yu (Charles Luk), Ch’an and Zen Teaching, third series (Berkeley, California: Shambhala Publications, 1973), p. 95.

17. Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa, edited by W. Y. Evans-Wentz (London: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 143.

18. Isaac K. Ezekiel, Kabir the Great Mystic (Punjab, India: Radha Soami Satsang Beas, 1973), p.

187.

19. Ibid., p. 129.

20. St. John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul, translated by E. Allison Peers (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1959), pp. 33-34.

21. Bubba Free John, The Method of the Siddhas (Los Angeles: The Dawn Horse Press, 1973), p. 255.

22. Bubba Free John, “Guru Enters the Devotee ” a talk to the Ashram on January 3, 1974.

23. Swami Muktananda, Bhagawan Nityananda (Ganeshpuri, India: Shree Gurudev Ashram, 1972), pp. 62, 31, 43.

24. Sri Gurudev Nityanand Mandir Patrika (29th April 1963), pp. 36, 29.

25. Mani Sahukar, Sai Baba: the Saint of Shirdi (Bombay, India: Somaiya Publications Pvt. Ltd, 1971), pp. 59-60.

26. Sayings of Ramakrishna (Madras, India: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1971), pp. 203, 288-289.

27. Arthur Osborne, The Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi (New York: Samuel Weiser, 1972), pp. 68-70.

28. Bubba Free John, Garbage and the Goddess, pp. 245-252.

Bubba Free John (Franklin Jones), The Knee of Listening (Los Angeles: The Dawn Horse Press, 1973), pp. 266-268.