THE SCIENCE OF BREATH

AND THE

PHILOSOPHY OF THE TATTVAS

TRANSLATED PROM THE SANSKRIT, WITH

INTRODUCTORY AND EXPLANATORY

ESSAYS ON

NATURE’S FINER FORCES

REPRINTED FROM “THE THEOSOPHIST” WITH

MODIFICATIONS

AND

ADDITIONS.

BY

RAMA

PRASAD, M.A., F.T.S.

Its one absolute attribute, which is itself, eternal, ceaseless Motion, is called

in esoteric parlance the “Great Breath,” which is the perpetual motion of the

Universe,

in the sense of limitless, everpresent Space.

—H. P. Blavatsky: The Secret Doctrine

SECOND AND REVISED EDITION

LONDON:

THEOSOPHICAL

PUBLISHING SOCIETY, 7, DUKE STREET. ADELPHI, W.C.

NEW YORK:

THE

PATH, 144, MADISON AVENUE.

MADRAS:

THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, ADYAR.

1894

THE H.P.B. PRESS,

42,

Henry Street, Regent’s Park,

London,

N.W.

(Printers

to the Theosophical Society)

Preface

A word of explanation is necessary with regard to the book now offered

to the public. In the 9th and 10th volumes of the theosophist I

wrote certain Essays on “Nature’s Finer Forces”. The subject of these

essays interested the readers of the Theosophist so much

that I was asked to issue the series of Essays in book form. I found that in order to make a book they must be almost entirely

rearranged, and perhaps rewritten. I was, however, not equal to

the task of rewriting what I had once written. I therefore determined to publish a translation of the book in Sanskrit on the Science of the Breath and the Philosophy

of the Tatwas. As, however, without these Essays the

book would have been quite unintelligible, I decided to add

them to the book by way of an illustrative introduction. This accordingly has been done. The Essays in the theosophist have been reprinted with

certain additions, modifications, and corrections.

Besides, I have written seven more Essays in order to make the explanations

more complete and authoritative. Thus there are altogether 15

introductory and explanatory Essays.

I was confirmed in this course by one more consideration. The book

contains a good deal more than the essays touched upon, and I thought it better

to lay all of it before the public.

The book is sure to throw a good deal of light upon the scientific

researches of the ancient Aryans of India, and it will

leave no doubt in a candid mind that the religion of ancient India had a

scientific basis. It is chiefly for this reason that I have drawn my

illustrations of the Tatwic Law from the Upanishads.

There is a good deal in the book that can only be shown to be true by

long and diligent experiment. Those who are devoted to the

pursuit of truth without prejudice will no doubt be ready to wait before they form any opinion about such portions of the book. Others it is

useless to reason with.

To the former class of students I have to say one word more. From my own

experience I can tell them that the more they study the book,

the more wisdom they are sure to find in it, and let me hope that ere long I shall have a goodly number of colleagues, who will with me try

their best to explain and illustrate the book still better,

and more thoroughly.

![]() Rama Prasad Merut (India) 5 November 1889

Rama Prasad Merut (India) 5 November 1889

CONTENTS

OF

Nature’s Finer Forces & Their

Influence on Human Life & Destiny

Part

1

I. The Tatwa………………………………………………………………………….. 3

II.

Evolution 10

III. The Mutual Relation of the

Tatwas and of the Principles….. 14

IV. Prana (I)………………………………………………………….. 19

V. Prana (II)………………………………………………………….. 30

VI. Prana (III)……………………………………………………….. 42

VII.

Prana (IV) 46

VIII.

The Mind (I) 48

IX. The Mind (II)……………………………………………………. 61

X. The Cosmic Picture Gallery……………………………………… 63

XI. The Manifestations of Psychic

Force………………………….. 70

XII.

Yoga The Soul (I) 72

XIII.

Yoga (II) 77

XIV.Yoga The Soul (III)………………………………….. 81

XV. The Spirit………………………………………………. 85

Part

2

XV. The Spirit……………………………………………………………………….. 88

Glossary…………………………………………………………………………… 107

I

– THE TATWA

The

tatwas are the five modifications of the great Breath.

Acting upon

prakriti, this Great breath throws

it into five states, having distinct vibratory motions,

and performing different functions. The first outcome of the Evolutionary State of parabrahma is the akasa tatwa. After this come in order the vayu,

the taijas, the apas and the prithivi. They are variously known as mahabhutas. The word akasa is

generally translated into English by the word ether.

Unfortunately, however, sound is not known to be the distinguishing quality of ether in modern English Science. Some few

might also have the idea that the modern

medium of light is the same as akasa. This, I believe, is

a mistake. The luminiferous ether is the subtle taijas tatwa, and not the akasa. All the five

subtle

tatwas might no doubt be called ethers,

but to use it for the word akasa, without any

distinguishing epithet, is misleading. We might call akasa

the sonoriferous ether, the vayu the

tangiferous ether, apas the gustiferous ether, and prithivi the odoriferous ether. Just as there

exists in the universe the luminiferous ether, an element of refined mater

without which it has been found that the phenomena of

light find no adequate explanation, so do there exist the four remaining ethers, elements of refined matter, without

which it will be found that the phenomena of

sound, touch, taste and smell find no adequate explanation.

The

luminiferous ether is supposed by Modern Science to be Matter in a most refined

state. It is the vibrations of this

element that are said to constitute light. The vibrations are said to take

place at right angles to the direction of the

wave. Nearly the same is the description of the taijas tatwa given in the book. It makes this tatwa move in an

upward direction, and the center of the direction is, of course, the

direction of the wave. Besides, it says that one whole

vibration of this element makes the figure of a triangle.

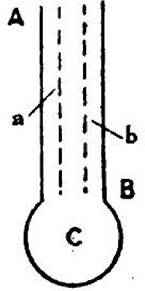

Suppose in the figure:

AB is the direction

of the wave; BC is the direction of the vibration. CA is the line along which,

seeing that in expansion

the symmetrical arrangements of the atoms of a body are not changed, the

vibrating atom must return to its symmetrical position in the line AB.

The taijas tatwa of the Ancients is then exactly the

luminiferous ether of the Moderns, so far as the nature of the vibration is

concerned. There is no exception, however, of the four remaining ethers, at all events in a

direct manner, in Modern Science. The vibrations of akasa, the soniferous ether, constitute

sound; and it is

quite necessary to recognize the distinctive character of this form of motion.

The experiment of the bell in a vacuum goes to prove that the vibrations

of atmosphere propagate sound. Any other media, however, such

as the earth and the metals, are known to transmit sound in various degrees. There must, therefore, be some one thing in all these

media which gives birth to sound the vibration that

constitutes sound. That something is the Indian akasa.

But akasa is allpervading, just as the luminiferous ether. Why, then, is not

sound transmitted to our ears when a vacuum is produced in the

belljar? The real fact is that we must make a difference between the vibrations of the elements that constitute sound and light, etc.,

and the vibrations in the media which transmit these

impressions to our senses. It is not the vibrations of the ethers the subtle tatwas that cause our perceptions, but the ethereal vibrations transferred to

different media, which are so many modifications of

gross matter the sthula Mahabhutas. The luminiferous aether is

present just as much in a darkened room as in the space

without. The minutest space within the dimensions of the surrounding walls themselves is not void of it. For all this the

luminosity of the exterior is not present in the interior.

Why? The reason is that our ordinary vision does not see the vibrations of the

luminiferous ether. It only sees the vibrations of the media that the ether

pervades. The capability of being set into ethereal vibrations varies with

different media. In the space without the darkened room the ether brings the atoms of the atmosphere into the necessary state of visual

vibration, and one wide expanse of light is presented to our

view. The same is the case with every other object that we see. The ether that

pervades the object brings the atoms of that object into the necessary state of

visual vibration. The strength of the ethereal vibrations

that the presence of the sun imparts to the ether pervading our planet is not

sufficient to evoke the same state in the dead matter of the darkening walls.

The internal ether, divided from the eternal one by this

dead mass, is itself cut off from such vibrations. The darkness of the room is thus the consequence, notwithstanding the presence therein

of the luminiferous ether. An electric spark in the vacuum of a

belljar must needs be transmitted to our eyes, because the glass of the jar which stands in contact with the internal luminiferous ether has a

good deal of the quality of being put into the state of

visual vibration, which from thence is transmitted to the external ether and

thence to the eye. The same would never be the case if we were to

use a porcelain or an earthen jar. It is this capability of

being put into the state of visual vibrations that we call transparency in

glass and similar objects.

To return to the soniferous ether (akasa): Every form of gross matter has,

to a certain extent, which varies with various forms, what

we may call auditory transparency.

Now I have to say

something about the nature of the vibrations. Two things must be understood in

this connection. In the first place the external form of the

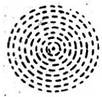

vibration is something like the hole of the ear:

It throws matter which is subject to it, into the form of a dotted

sheet:

These dots are little points, rising above the common

surface so as to produce microscopic pits in the sheet. It is said to move by

fits and starts (sankrama), and to move in all directions (sarvatogame). It means to say that the impulse falls back upon itself along the

line of its former path, which lies on all sides of the direction

of the wave:

It

will be understood that these ethers produce in gross media vibrations similar

to their own. The form, therefore, into which the auditory vibrations throw the

atmospheric air is a true clue to the form of the ethereal

vibration. And the vibrations of atmospheric air discovered by Modern Science

are similar.

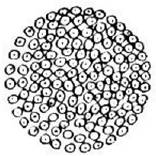

Now

we come to the tangiferous ether (vayu). The vibrations of this ether are described as being spherical in

form, and the motion is said to be at acute angles to the wave (tiryak). Such is the representation of these

vibrations on the plane of the paper:

The remarks about the transmission

of sound in the case of akasa apply here too, mutatis mutandis. The gustiferous ether (apas tatwa) is said to resemble

in shape the half moon. It is, moreover, said to move downward. This direction is opposite to that of the luminiferous ether.

This force therefore causes contraction. Here is the

representation of the apas vibrations on the plane of paper:

The process of contraction will be considered when I come to the

qualities of the tatwas. The odoriferous ether

(prithivi) is said to be quadrangular in shape, thus:

This is said to move in the middle. It neither moves at

right angles, nor at acute angles, nor upwards, nor downwards, but it moves

along the line of the wave. The line and the quadrangle are in the same plane.

These

are the forms, and the modes of motion, of the five ethers. Of the five

sensations of men, each of these gives birth to one, thus:

(1)

Akasa, Sonorifierous ether, Sound;

(2) Vayu, Tangiferous

ether, Touch; (3) Taijas, Luminfierous

ether,

Color; (4) Apas, Gustiferous

ether, Taste; (5) Prithivi, Odoriferous

ether, Smell.

In

the process of evolution, these coexisting ethers, while retaining their

general, relative forms and primary qualities, contract the qualities of the

other tatwas. This is known

as the process of panchikarana, or division

into five.

If we take, as

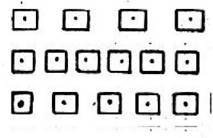

our book does, H, P, R, V and L to be the algebraic symbols for (1), (2), (3),

(4), and (5), respectively, after panchikarana the ethers assume the following forms:

One molecule of each ether, consisting of eight atoms, has four

of the originalprinciple ethers, and one of the remaining

four.

The following table will show the five

qualities of each of the

tatwas after panchikarana:

|

|

|

Sound |

Touch |

Taste |

Color |

Smell |

|

(1) |

H |

ordinary |

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

(2) |

P |

very light |

cool |

acid |

light blue |

acid |

|

(3) |

R |

light |

very hot |

hot |

red |

hot |

|

(4) |

V |

heavy |

cool |

astringent |

white |

astringent |

|

(5) |

L |

deep |

warm |

sweet |

yellow |

sweet |

It might be remarked here that the subtle tatwas exist now in the universe on four

planes. The higher of these planes differ from the lower in having a greater

number of vibrations per second. The four planes are:

(1)

Physical (Prana); (2) Mental

(Manas); (3) Psychic (Vijnana); (4) Spiritual (Ananda) I shall discuss, however, some of the

secondary qualities of these

tatwas.

(1) Space ~ This is

a quality of the akasa tatwa. It has been

asserted that the vibration of this ether is shaped like the hole of the ear, and

that in the body thereof are microscopic points (vindus). It follows evidently that

the interstices between the points serve to give space to ethereal minima, and

offer them room for locomotion (avakasa).

(2)

Locomotion ~ This is the quality of the vayu tatwa. Vayu is a form of motion itself, for motion in all directions is

motion in a circle, large or small. The vayu tatwa itself has the form of spherical motion. When to the

motion which keeps the form of the different ethers is added to the stereotyped

motion of the vayu, locomotion is

the result.

(3)

Expansion ~ This is the quality of the taijas tatwa. This follows evidently from the shape

and form of motion which is given to this ethereal vibration. Suppose ABC is a

lump of metal:

If we applyfire to it,

the luminiferous ether in it is set in motion, and that drives the gross atoms

of the lump into similar motion. Suppose (a) is an atom. This being impelled to assume

the shape of the taijas, vibration goes towards (a’),

and then takes the symmetricalposition of (a’). Similarly does every point

change its place round the center of the piece of metal. Ultimately the whole piece assumes the

shape ofA’B’C’. Expansion is thus the result.

(4)

Contraction ~ This is the quality of the apas tatwa. As has been remarked before, the

direction of this ether is the reverse of the agni, and it is therefore easy to understand that contraction

is the result of the play of this tatwa.

(5)

Cohesion ~ This is the quality of the prithivi tatwa. It will be seen that this is the

reverse of akasa. Akasa gives room for locomotion, while prithivi resists it. This is the natural result

of the direction and shape of this vibration. It covers up the spaces of the akasa.

(6) Smoothness ~

This is a quality of the apas

tatwa. As the atoms of any body in contraction come near each

other and assume the semilunar shape of the apas, they must easily glide over

each other. The very shape secures easy motion for the atoms.

This, I believe, is

sufficient to explain the general nature of the tatwas. The different phases of

their manifestation on all the planes of life will be taken up in their proper

places.

II – EVOLUTION

It

will be very interesting to trace the development of man and the development of

the world according to the theory of the tatwas.

The

tatwas, as we have already seen, are

the modifications of Swara. Regarding Swara, we find in our book: “In the Swara are the Vedas and the shastras, and in the Swara is music. All the world is in the Swara; Swara is the spirit itself.” The proper translation of the

word Swara is “the

current of the lifewave”. It is that wavy motion which is the cause of

the evolution of cosmic undifferentiated matter into the

differentiated universe, and the involution of this into the primary state of

nondifferentiation, and so on, in and out, forever and ever. From whence does

this motion come? This motion is the spirit itself. The word atma used in the book, itself carries the idea of

eternal motion, coming as it does from the root at, eternal motion; and it may be

significantly remarked, that the root at is connected with (and in fact is simply another form of)

the roots ah, breath, and as, being. All these roots have for their original the sound

produced by the breathing of animals. In The Science of Breath the symbol for inspiration is sa, and for expiration ha. It is easy to see how these symbols are connected

with the roots as and ah. The current of lifewave spoken of above is

technically called Hansachasa, i.e., the

motion of ha and sa. The word Hansa, which is taken to mean God, and is made so much of in

many Sanskrit works, is only the symbolic representation of the eternal processes

of life ha and sa.

The primeval current of lifewave is, then, the same which

in man assumes the form of inspiratory and expiratory motion of the lungs, and

this is the allpervading source of the evolution and the involution of the

universe.

The

book goes on: “It is the Swara that has given form to the first accumulations of the

divisions of the universe; the Swara causes involution and evolution; the Swara is God Himself, or more properly the great Power (Mahashwara).” The Swara is the manifestation of the impression

on matter of that power which in man is known to us as the power that knows

itself. It is to be understood that the action of this power never

ceases. It is ever at work, and evolution and involution are the very necessity

of its unchangeable existence.

The

Swara has two different states. The

one is known on the physical plane as the sunbreath, the other as the

moonbreath. I shall, however, at the present stage of evolution designate them

as positive and negative respectively. The period during which this

current comes back to the point from whence it started is known as the night of

parabrahma. The positive

or evolutionary period is known as the day of parabrahma; the negative or involutionary

portion is known as the night of parabrahma. These nights and days follow each other without

break. The subdivisions of this period comprehend all the phases of existence,

and it is therefore necessary to give her the scale of time according to the

Hindu Shastras.

~ The Divisions of Time ~

I

shall begin with a Truti as the least

division of time. 262/3 truti = 1 nimesha

= 8/45 second.

18 nimesha

= 1 kashtha = 31/5 seconds = 8 vipala.

30

kashtha = 1 kala = 13/5 minutes = 4 pala. 30 kala = 1 mahurta

= 48 minutes = 2 ghari.

30

mahurta = 1 day and night = 24 hours =

60 ghari.

30

days and nights and odd hours = 1 Pitruja day and night = 1 month and odd hours.

12

months = 1 Daiva day and night

= 1 year = 365 days, 15″, 30′, 31”.

365

Daiva days and nights = 1 Daiva year. 4,800 Daiva years = 1 Satya yuga.

3,600

Daiva years = 1 Treta yuga.

2,400

Daiva years = 1 Dwapara yuga.

1,200

Daiva years = 1 Kali yuga.

12,000

Daiva years = 1 Chaturyugi (four yuga). 12,000 Chaturyugi = 1 Daiva

yuga.

2,000

Daiva yuga = 1 day and

night of Brahma. 365 Brahmic

days and nights = 1 year of Brahma. 71 Daiva yuga = 1 Manwantara.

12,000

Brahmic years = 1 Chaturyuga of Brahma, and

so one.

200

yuga of Brahma = 1 day and night of parabrahma.

These

days and nights follow each other in eternal succession, and hence eternal

evolution and involution.

We

have thus five sets of days and night: (1) Parabrahma, (2) Brahma, (3) Daiva, (4) Pitrya, (5) Manusha. A sixth is

the Manwantara day, and the Manwantara night (pralaya).

The

days and nights of parabrahma follow each

other without beginning or end. The night (the negative period and the

day (the positive period) both merge into the susumna (the conjunctive period) and merge into

each other. And so do the other days and nights. The days all through this

division are sacred to the positive, the hotter current, and the nights

are sacred to the negative, the cooler current. The impressions of names and

forms, and the power of producing an impression, lie in the positive phase of

existence. Receptivity is given birth to by the negative current.

After

being subjected to the negative phase of parabrahma, Prakriti, which follows

parabrahma like a shadow, has

been saturated with evolutionary receptivity; as the hotter current sets in,

changes are imprinted upon it, and it appears in changed forms. The first imprint

that the evolutionary positive current leaves upon Prakriti is known as akasa. Then, by and by the remaining ethers

come into existence. These modifications of Prakriti are the ethers of the first stage.

Into

these five ethers, as now constituting the objective phase, works on the

current of the Great Breath. A further development takes place. Different

centers come into existence. The akasa throws them into a form that gives room for locomotion.

With the beginning of the vayu

tatwa these elementary ethers are thrown into the form of spheres. This

was the beginning of formation, or what may also be called solidification.

division

into five takes place. In this Brahmic sphere in which the new ethers have good

room for locomotion, the taijas tatwa now comes into

play, and then the apas tatwa. Every tatwic

quality is generated into, and preserved in, these spheres by these currents. In

process of time we have a center and an atmosphere. This sphere is the

selfconscious universe.

In

this sphere, according to the same process, a third ethereal state comes into

existence. In the cooler atmosphere removed from the center another class of

centers comes into existence. These divide the Brahmic state of matter into two

different states. After this comes into existence another state of matter whose centers

bear the names of devas or suns.

We

have thus four states of subtle matter in the universe:

(1) Prana, life matter,

with the sun for center; (2) Manas, mental matter, with the manu for center; (3) Vijnana, psychic matter, with Brahma for center; (4) Ananda, spiritual matter, with parabrahma as the infinite substratum.

Every

higher state is positive with regard to the lower one, and every lower on is

given birth to by a combination of the positive and negative phase of the

higher.

(1)

Prana has to do with

three sets of days and nights in the above division of time: (a) Our ordinary days and

nights; (b) The bright and dark half of the month which are called the pitrya

day and night; (c) The northern and southern halves of the years, the day and

night of the devas.

These

three nights acting upon earthmatter impart to it the receptivity of the cool,

negative shady phase of lifematter. These nights imprint themselves on the

respective days coming in after it. The earth herself thus becomes a living

being, having a north pole, in which a central force draws the needle towards

itself, and a south pole in which is centered a for which is, so to speak, the

shade of the north polar center. It has also always a solar force centered

in the eastern half, and the lunar the shade of the former

centered in the western half.

These

centers come, in fact, into existence even before the earth is manifested on

the gross plane. So too do the centers of other planets come into existence.

As the sun presents himself to the manu there come into existence two states

of matter in which the sun lives and moves the positive and the negative. As

the solar prana, after having

been for some time subjected to the negative shady state, is subjected in

its revolutionary course to the source of its positive phase, manu, the figure of manu is imprinted upon it. This manu is, in fact, the universal mind, and all the planets

with their inhabitants are the phases of his existence. Of this, however, more

heareafter. At present we see that earthlife or Terrestrial Prana has four centers of force.

When

it has been cooled by the negative current, the positive phase imprints itself

upon it, and earthlife in various forms comes into existence. The essays on prana will explain this more clearly.

(2)

Manas: this has to

do with manu. The suns

revolve round these centers with the whole of their atmospheres of prana. This system gives birth to the lokas or spheres of life, of which the planets are one class.

These lokas have been enumerated by Vyasa in his

commentary on the Yogasutra (III. Pada, 26th

Sutra). The aphorism

runs thus:

“By

meditation upon the sun is obtained a knowledge of the physical creation.”

On

this, the revered commentator says: “There are seven lokas (spheres of existence).”

(1)

The Bhurloka: this extends

to the Meru; (2) Antareikshaloka: this extends

from the surface of the Meru to the Dhru, the polestar, and contains the planets, the nakstatras, and the stars; (3) Beyond that is

the swarloka: this is

fivefold and sacred to Mahendra; (4) Maharloka: This is sacred to the Prajapati; (5) Janaloka; (6) Tapas loka, and; (7) Satya loka. These three (5, 6, and 7) are sacred

to Brahma.

It

is not my purpose to try at present to explain the meaning of these lokas. It is sufficient for my present purpose

to say that the planets, the stars, the lunar mansions are all impressions of manu, just as the organisms of the earth are the

impressions of the sun. The solar prana is prepared for this impression during the manwantara night.

Similarly,

Vijnana has to do with the nights and

days of Brahma, and Ananda with those of Parabrahma.

It

will thus be seen that the whole process of creation, on whatever plane of

life, is performed most naturally by the five tatwas in their double modifications, the

positive and negative. There is nothing in the universe that the Universal Tatwic

Law of Breath does not comprehend.

After this brief exposition of the theory of tatwic

evolution comes a series of Essays, taking up all the subtle states

of matter one by one, and describing more in detail the working of the tatwic

law in those planes, and also the manifestations of these planes of

life in humanity.

III THE MUTUAL RELATION OF THE TATWAS AND OF THE

PRINCIPLES

The

akasa is the most important of all the

tatwas. It must, as a matter of

course, precede and follow every change of state on every plane of life.

Without this there can be no manifestation or cessation of forms. It is

out of akasa that every

form comes, and it is in akasa that every

form lives. The akasa is full of forms

in their potential state. It intervenes between every two of the five tatwas, and between every two of

the five principles.

The

evolution of the tatwas is always part

of the evolution of a certain definite form. Thus the manifestation of the

primary tatwas is with the

definite aim of giving what we may call a body, a Prakritic form

to the Iswara. In the bosom

of the Infinite Parabrahma, there are

hidden unnumerable such centers. One center takes under its influence a

certain portion of the Infinite, and there we find first of all

coming into existence the akasa

tatwa. The extent of this akasa limits the

extent of the Universe, and out of it the Iswara is to come. With this end comes out of

this akasa the Vayu tatwa. This pervades the whole Universe and

has a certain center that serves to keep the whole expanse together, and

separate as one whole, from other universes (Brahmandas).

It

has been mentioned, and further on will be more clearly explained, that every tatwa has a positive and a negative

phase. It is also evident on the analogy of the sun that places more distant

from the center are always negative to those which are nearer. We might say that

they are cooler than these, as it will be seen later on the heat is not

peculiar to the sun only, but that all the higher centers have a greater amount of heat

than even the sun itself.

Well

then, in this Brahmic sphere of Vayu, except for some space near the parabrahmic akasa, every atom of the vayu is reacted upon by an opposite force. The more

distant and therefore the cooler one reacts upon the nearer and therefore the

hotter. The equal and opposite vibrations of the same force cancel each

other, and both together pass into the akasic state. Thus, while some of this

space remains filled up by the Brahmic Vayu on account of the constant outflow of this tatwa from the parabrahmic akasa, the remainder is rapidly turned into akasa. This akasa is the mother of the Brahmic agni tatwa. The agni tatwa working similarly gives birth through

another akasa to the apas, and this similarly to the prithivi. This Brahmic prithivi thus contains the qualities of all the

preceding tatwas besides a fifth

one

of its own.

The first stage of the Universe, the ocean of psychic

matter has now come into existence in its entirety. This matter is,

of course, very, very fine, and there is absolutely no grossness in it as

compared with the matter of the fifth plane. In this ocean shines the

intelligence of Iswara, and this

ocean, with everything that might be manifest in it, is the selfconscious

universe.

In

this psychic ocean, as before, the more distant atoms are negative to the

nearer ones. Hence, except a certain space which remains filled with the

psychic prithivi on account of

the constant supply of this element from above, the rest begins to change into

an akasa. This second akasa is full of what are called Manus in their potential state. The Manus are so many groups of certain mental forms, the

ideals of the various genera and species of life to appear further on. We have

to do with one of these.

Impelled by the evolutionary current of the Great Breath, manu comes out of

this akasa, in the same

way as Brahma did out of the parabrahmic akasa. First and

uppermost in the mental sphere is the Vayu, and then in

regular order the taijas, the apas, and the prithivi. This mental

matter follows the same laws, and similarly begins to pass

into the third akasic state, which is full of innumerable suns. They come out

in the same way, and begin to work on a similar plan, which will be better

understood here than higher up.

Everybody can test here for himself that the more distant portions of the

solar system are cooler than the nearer ones. Every little atom of Prana is

comparatively cooler than the adjacent one towards the sun from itself. Hence

equal and opposite vibrations cancel each other. Leaving, therefore, a certain space near the sun as always filled up with the tatwas of Prana, which are

there being constantly supplied from the sun, the rest of the

Prana passes into the akasic state.

It might be noted down here that the whole of this Prana is made up of

innumerable little points. In the future I shall speak

of these points of as trutis, and might say here that it is these trutis that appear on

the terrestrial plane as atoms (anu or paramanu). They might

be spoken of as solar atoms. These solar atoms are of various

classes according to the prevalence of one or more of the constituent tatwas.

Every point of Prana is a perfect picture of the whole

ocean. Every other point is represented in every point. Every

atom has, therefore, for its constituents, all the four tatwas, in varying

proportions according to its position in respect of others. The

different classes of these solar atoms appear on the terrestrial plane as the various elements of chemistry.

The spectrum of every terrestrial element reveals the color or colors of

the prevalent tatwa or tatwas of a solar atom of that substance. The greater the heat to which any

substance is subjected the nearer does the element

approaches its solar state. Heat destroys for the time being the terrestrial

coatings of the solar atoms.

The spectrum of sodium thus shows the presence of the yellow prithivi, that of

lithium, the red agni and the yellow prithivi, that of

cesium, the red agni, the green admixture, the yellow prithivi, and the blue

vayu. Rubidium shows red, orange, yellow, green and blue, i.e., the agni, prithivi and agni, prithivi, vayu and prithivi, and vayu. These classes of solar atoms that

make up all put altogether, the wide expanse of the solar prana, pass into the

akasic state. While the sun keeps up a constant supply of these atoms, those that are passing into the akasic state pass on the other

side into the planetary vayu. Certain measured portions of

the solar akasa

naturally separate themselves from others, according to

the differing creation that is to appear in those portions.

These portions of akasa are called lokas. The earth itself is a loka called the Bhurloka. I shall take

up the earth for further illustration of the law.

That portion of the solar akasa that is the immediate

mother of the Earth, first gives birth to the terrestrial Vayu. Every element is now

in the state of the Vayu tatwa, which may now be called gaseous. The Vayu

tatwa is spherical in shape, and thus the gaseous planet

bears similar outlines. The center of this gaseous sphere

keeps together round itself the whole expanse of gas. As soon as this gaseous sphere comes into existence, it is subjected to the following influences

among others:

the nearer ones

and vice versa.

The

first influence has a double effect upon the gaseous sphere. It imparts more

heat to the nearer hemisphere than to the more distant one. The superficial air

of the nearer hemisphere having contracted a certain amount of solar energy, rises

towards the sun. Cooler air from below takes its place. But where does the

superficial air go? It cannot pass beyond the limit of the terrestrial sphere,

which is surrounded by the solar akasa through which comes a supply from the solar Prana. It therefore begins to move in a

circle, and thus a rotary motion is established in the sphere. This is the origin

of the earth’s rotation upon its axis.

Again,

as a certain amount of the solar energy is imparted to the gaseous terrestrial

sphere, the impulse of the upward motion reaches the center itself. Therefore

that center itself, and along with it the whole sphere, moves towards the sun.

It cannot, however, go on in this direction, for a nearer approach would destroy that

balance of forces that gives the earth its peculiarities. A loka that is nearer to the sun than our planet

cannot have the same conditions of life. Hence, while the sun draws the earth

towards itself, those laws of life that have given it a constitution, on

which ages must roll on, keep it in the sphere they have assigned

to it. Two forces thus come into existence. Drawn by one the earth would go

towards the sun; checked by the other it must remain where it is. These are the

centrifugal and the centripetal forces, and their action results in

giving the earth its annual revolution.

Secondly,

the internal action of the gaseous atoms upon each other ends in the change of

the whole gaseous sphere, except the upper portion, into the akasic state. This

akasic state gives birth to the igneous (pertaining to the agni tatwa) state of terrestrial matter. This

changes similarly into the apas, and this again

into the prithivi.

The

same process obtains in the changes of matter with which we are now familiar.

An example will better illustrate the whole law.

Take ice. This is solid, or what the Science of Breath

would call in the state of prithivi. One quality

of the

prithivi tatwa, the reader

will remember, is cohesive resistance. Let us apply heat to this ice. As this

heat passes into the ice, it is indicated by the thermometer. When the

temperature rises to 78 degrees, the ice changes its state. But the thermometer

no longer indicates the same amount of heat. 78 degrees of heat have

become latent.

Let

us now apply 536 degrees of heat to a pound of boiling water. As is generally

known, this great quantity of heat becomes latent while the water passes into

the gaseous state.

Now

let us follow the reverse process. To gaseous water let us apply a certain

amount of cold. When this cold becomes sufficient entirely to counteract the

heat that keeps it in the gaseous state, the vapor passes into

the akasa state, and

from thence into the taijas state. It is

not necessary that the whole of the vapor should at once pass into the next

state. The change is gradual. As the cold is gradually passing into the

vapor, the taijas modification

is gradually appearing out of, and through the intervention of akasa, into which it had passed during latency. This is

being indicated on the thermometer. When the whole has passed into the igneous

state, and the thermometer has indicated 536 degrees, the second akasa comes into existence. Out of this second akasa comes the liquid state at the same temperature,

the

whole heat having again passed into the akasa state, and therefore no longer indicated by the thermometer.

When cold is applied to this liquid, heat again begins to

come out, and when it reaches 78 degrees, this heat having come out of and

through the akasa, into which it

had passed, the whole liquid had passed into the igneous state. Here it again

begins to pass into the akasa state. The

thermometer begins to fall down, and out of this akasa begins to come the prithivi state of water ice.

Thus

we see that the heat which is given out by the influence of cold passes into

the akasa state, which becomes the

substratum of a higher phase, and the heat which is absorbed passes into

another akasa state, which

becomes the substratum of a lower phase.

It

is in this way that the terrestrial gaseous sphere changes into its present

state. The experiment described above points out many important truths about

the relation of these tatwas to each other.

First

of all it explains that very important assertion of the Science of Breath which

says that every succeeding tatwic state has the qualities of all the foregoing

tatwic states. Thus we see that as the gaseous state of water is being acted

upon by cold, the latent heat of steam is being cancelled and passing into the akasa state. This cannot but be the case, since equal and

opposite vibrations of the same force always cancel each other, and the result

is the akasa. Out of this

comes the taijas state of matter. This is

that state in which the latent heat of steam becomes patent. It will be

observed that this state has no permanence. The taijas form of water, as indeed any other

substance, cannot exist for any length of time, because the major part

of terrestrial matter is in the lower and therefore more negative states of apas and prithivi, and whenever for any cause any substance passes into the

taijas state, the surrounding

objects begin at once to react upon it with such force as at once to force it

into the next akasa state. Those

things that now live in the normal state of the apas or the prithivi find it quite against the

laws of their existence to remain, except under external influence, in the taijas (igneous) state. Thus an

atom of gaseous water before passing into the liquid state has already remained

in the three states, the akasa, the gaseous,

and the taijas. It must,

therefore, have all the qualities of the three tatwas, and so it no doubt has. Cohesive

resistance is only wanted, and that is the quality of the prithivi tatwa.

Now

when this atom of liquid water passes into the icy state, what do we see? All

the states that have preceded must again show themselves. Cold will cancel the

latent heat of the liquid state, and the akasa state will come out. Out of this akasa state is sure to come the gaseous state. This

gaseous (Vayava) state is

evidenced by the gyrations and other motions that are set up in the body of the

liquid by the mere application of the cold. The motion, however, is not

of very long duration, and as they are ceasing (passing into the akasa state) the taijas state is coming out. This too,

however, is not of long duration, and as this is passing into the akasa state, the ice is coming into existence.

It

will be easy to see that all four states of terrestrial matter exist in our

sphere. The gaseous (Vayava) is there in what

we call the atmosphere; the igneous (taijas) is the normal temperature of earth life; the liquid (apas) is the ocean; the solid (prithivi) is the terra firma. None of these states, however,

exists quite isolated from the other. Each is constantly invading the domain of

the other, and thus it is difficult

to

find any portion of space filled up only with matter in one state. The two

adjacent tatwas are found intermixed with each other to a greater degree

than those that are removed from each other by an intermediate

state. Thus prithivi will be found

mixed up to a greater extent with water than with agni and vayu, apas with agni than with vayu, and vayu with agni more than with any other. It would thus appear from

the above, according to the science of tatwas, that the flame and other luminous bodies on earth are

not in the terrestrial taijas

(igneous) state. They are in or near the solar state of matter.

IV – PRANA (I)

The

Centers of Prana; The Nadis; The Tatwic Centers of Life;

The Ordinary Change of Breath

Prana, as already

expressed, is that state of Tatwic matter which surrounds the sun, and in which

moves the earth and other planets. It is the state next higher than matter in

the terrestrial state. The terrestrial sphere is separated from the solar Prana by an akasa. Thisakasa is the immediate mother of the terrestrial vayu whose native color is blue. It is on this account

that the sky looks blue.

Although

at this point in the heavens, the Prana changes into akasa, which gives birth to the terrestrial Vayu, the rays of the sun that fall on the sphere from

without are not stopped in their inward journey. They are refracted, but move

onwards into the terrestrial sphere all the same. Through these rays the ocean of Prana, which surrounds our sphere, exerts upon it an

organizing influence.

The

terrestrial Prana the

earthlife that appears in the shape of all the living organisms of our planet

is,

as a whole, nothing more than a modification of the solar Prana.

As

the earth moves round her own axis and round the sun, twofold centers are

developed in the terrestrial Prana. During the diurnal rotation every place, as it is

subjected to the direct influence of the sun, sends forth the positive

lifecurrent from the East to the West. During the night the same place sends forth the

negative current.

In

the annual course the positive current travels from the North to the South

during the six months of summer the day of the devas and the negative during

the remaining six months the night of the devas.

The

North and East are thus sacred to the positive current; the opposite quarters

to the negative current. The sun is the lord of the positive current, the moon of

the negative, because the negative solar prana comes during the night to the earth from the moon.

The

terrestrial prana is thus an

ethereal being with double centers of work. The first is the northern, the second the

southern. The two halves of these centers are the eastern and western centers.

During the six months of summer the current of life runs from the North

to the South, and during the months of winter the negative current goes the

other way.

With

every month, with every day, with every nimesha this current completes a minor course, and while this

current continues in this course the diurnal rotation gives it an eastern or

western direction. The northern current runs during the day of man from East

to West, and during the night from West to East. The directions of the other

current are respectively opposite to the above. So practically there are only two

directions the eastern and western. The difference of the northern and

southern currents is not practically felt in terrestrial life. These two

currents produce in the terrestrial prana two distinguishable modifications of the composing

ethers. The rays of either of these ethereal modifications proceeding from

their different centers run into each other the one giving life, strength, form and other

qualities to the other. Along the rays emerging from the northern center, run

the currents of positive prana; along those

emerging from the southern, the currents of negative prana. The eastern and western channels of these

currents are respectively called Pingala and Ida, two of the

celebrated

nadis of the Tantrists. It will be better to discuss the other bearings of Prana, when we have localized it in the human body.

The

influence of this terrestrial Prana develops two centers of work in the gross matter that is

to form a human body. Part of the matter gathers round the northern, and part

round the southern center. The northern center develops into the brain; the

southern into the heart. The general shape of the terrestrial Prana is something like an ellipse. In this the northern

focus is in the brain; the southern in the heart. The column

along which the positive matter gathers runs between these foci.

The

line in the middle is the place where the eastern and western right and left

divisions of the column join. The column is the medulla oblongata the

central line is also susumna, the right and

left divisions the Pingala and Ida. The rays of Prana that diverge either way from these nadis are only their ramifications,

and constitute together with them the nervous system.

The

negative Prana gathers round

the southern center. This, too, takes a form similar to the former. The right and left

divisions of this column are the right and left divisions of the heart.

Each

division has two principal ramifications, and each ramification again ramifies

into others. The two openings either way are one a vein, and one an artery,

the four opening into four chambers the four petals of the lotus of the

heart. The right part of the heart again, with all its ramifications, is called

Pingala, the left Ida, and the middle part susumna.

There

is reason to think, however, that the heart only is spoken of as the lotus,

while the three foregoing names are set apart for the nervous system. The

current of Prana works forward

and backward, in and out. The cause of this lies in the momentary of the being

of Prana. As the year

advances, every moment a change of state takes place in the terrestrial prana, on account of the varying strengths of the solar and lunar

currents. Thus, every moment is, strictly speaking, a new being of Prana. As Buddha says, all life is momentary. The

Moment that is the first to throw into matter the germ that will develop the two centers

is the first cause of organized life. If the succeeding Moments are friendly in

their tatwic effect to the first cause, the organism gains strength and

develops; if not, the impulse is rendered fruitless. The general effect of these

succeeding moments keeps up general life; but the impulse of any one moment

tends to pass off as the others come in. A system of forward and backward

motion is thus established. One Moment of Prana proceeding from the center of work

goes to the farthest ends of the gross vessels nerves and blood vessels of

the organism. The succeeding moment gives it, however, the backwards

impulse. A few moments are taken in the completion of the forward impulse, and

the determination of the backward one. This period differs in different

organisms. As the Prana runs forward, the

lungs inspire; as it recedes, the process of expiration sets in.

The

Prana moves in the Pingala when it moves from the northern center

towards the east, and from the southern towards the west; it moves in Ida when it moves from the northern center towards the

west, and from the southern center towards the east. This means that in the

former case the Prana moves from the brain,

towards the right, through the heart, to the left and back to the brain; and

from the heart to the left through the brain to the right back to the heart. In

the latter the case is the reverse. To use other terms, in the former case the Prana moves from the nervous system to the right through

the

system

of blood vessels to the left, and back again to the nervous system; or, from

the system of blood vessels to the left through the nervous system to the

right, and back again to the system of blood vessels. These two currents

coincide. In the latter the case is the reverse. The left part of the body containing the

nerves and the blood vessels may be called Ida, the right the Pingala. The right and left bronchi form as

well the part respectively of Pingala and Ida, as any other

parts of the right and left divisions of the body. But what is susumna? One of the names of susumna is sandhi, the place where the two Ida and Pingala join. It is really that place from which the Prana may move either way right or left

or, under certain circumstances, both ways. It is that place which the Prana must pass when it changes from the right to the

left, and from the left to the right. It is therefore booth the spinal canal and the

cardiac canal. The spinal canal extends from the Brahmarandhra, the northern center of Prana through the whole vertebral column (Brahmadanda). The cardiac canal extends from the southern center

midway between the two lobes of the heart. As the Prana moves from the spinal canal towards the

right hand to the heart, the right lung works; the breath comes in and out of

the right nostril. When it reaches the southern canal, you cannot feel the breath

out of either nostril. As, however, it goes out of the cardiac canal to the

left, the breath begins to come out of the left nostril, and flows through that

until the Prana again reaches

the spinal canal. There, again, you cease to feel the breath out of either

nostril. The effect of these two positions of Prana is identical upon the flow of breath, and, therefore, I

think that both the northern and southern canals are designated by susumna. If we may speak in this

way, let us imagine that a plane passes midway between the spinal and cardiac

canals. This plane will pass through the hollow of the susumna. But let it be understood that there

is no such plane in reality. It will perhaps be more correct to say that

as the rays of the positive Ida and Pingala spread either way as nerves, and those

of the negative as bloodvessels, the rays of susumna spread all over the body midway

between the nerves and blood vessels, the positive and negative nadis. The following is the description of susumna in the Science of Breath:

“When the breath goes in and out, one moment by the

left and the other by the right nostril, that too is susumna. When Prana is in that nadi the fires of death burn; this is called vishuva. When it moves one moment in the

right, and the other in the left, let it be called the Unequal State (vishamabhava); when it moves thorough

both at once, the wise have called it vishuva“

“[It

is susumna] at the time

of the passing of the Prana from the Ida into the Pingala, or vice versa; and also of the change of one tatwa into another.”

Then

the susumna has two other

functions. It is called vedoveda

in one of its manifestations, and sandhyasandhi in the other. As, however, the right and left directions

of the cardiac Prana coincide with

the left and right of the spinal current, there are some writers who dispense

with the double susumna. According to

them, the spinal canal alone is the susumna. The Uttaragita

and Latachakra nirupana are works in this class. This method of

explanation takes away a good deal of difficulty. The highest

recommendation of this view is its comparative simplicity. The right side

current from the heart, and the left side current from the spine may both

be reckoned without difficulty as the left side spinal currents, and so may the

remaining two currents be reckoned as the right side spinal currents.

One more consideration is in favor of this view. The nervous system

represents the sun, the system of

blood

vessels the moon. Hence the real force of life dwells in the nerves. The

positive and negative the solar and lunar phases of life matter are only

different phases of Prana, the solar

matter. The more distant and therefore the cooler matter is negative to

the nearer, and therefore, the hotter. It is solar life that manifests

itself in the various phases of the moon. To pass out of technicalities, it is

nervous force that manifests itself in various forms, in the system of blood

vessels. The blood vessels are only the receptacles of nervous force. Hence, in

the nervous system, the real life of the gross body is the true Ida, Pingala and susumna. These are,

in such a case, the spinal column, and the right and left sympathetics,

with all their ramifications throughout the body.

The

development of the two centers is thus the first stage in the development of

the fetus. The matter that gathers up under the influence of the northern

center is the spinal column; the matter that gathers up round the

southern center is the heart. The diurnal rotation divides these columns or

canals into the right and left divisions. Then the correlative influence

of these two centers upon each other develops an upper and lower division in each

of these centers. This happens somewhat in the same way, and on the same principle,

as a Leyden jar is charged with positive electricity by a negative rod. Each of

these centers is thus divided into four parts:

(1)

The right side positive, (2) the left side positive, (3) the right side

negative, and (4) the left side negative.

In

the heart these four divisions are called the right and left auricles and

ventricles. The Tantras style these four divisions the four petals of the cardiac

lotus, and indicate them by various letters. The positive petals of the heart

form the center from which proceed the positive blood vessels, the arteries; the negative

petals are the starting points of the negative blood vessels, the veins. This

negative prana is pregnant with

ten forces:

(1)

Prana, (2) Apana, (3) Samana, (4) Vyana, (5) Udana, (6) Krikila, (7) Naga, (8) Devadatta, (9) Dhavanjaya, (10) Kurma.

These

ten forces are called vayu. The word vayu is derived from the root va, to move, and means nothing more

than a motive power. The Tantrists do not mean to give it the idea of a gas.

Henceforth I shall speak of the vayu as the forces or motive powers of prana. These ten manifestations of Prana are reduced by some writers to the

first five alone, holding that the remaining ones are only modifications of the former,

which are the allimportant of the functions of prana. This, however, is only a question of division. From

the left side positive petal the prana gathers up into a nadi that ramifies within the chest into the lungs,

and again gathers up into a nadi that opens into

the right side negative petal. This entire course forms something like a circle (chakra). This nadi is called in modern science the pulmonary artery and

vein. Two lungs come into existence by the alternate workings of the positive

and negative prana of the eastern

and western powers.

Similarly,

from the right side positive petal branch several nadi that go both upwards and downwards in two directions,

the former under the influence of the northern, the latter under the influence

of the southern powers. Both these nadi open after a circular march throughout the upper and lower

portions of the body into the left side negative petal.

Between

the left side positive and the right side negative petal is one chakra (disk). This chakra comprises the pulmonary artery, the

lungs, and the pulmonary vein. The chest gives room to this chakra, which is positive with respect to the lower

portions of the body, in which run the ramifications of the lower chakra, which latter joins the right side positive and

the left side negative petals.

In

the above chakra (in the cavity

of the chest) is the seat of prana, the first and most important of the ten

manifestations. Inspiration and expiration being a true index of the changes of

prana, the pulmonary

manifestations thereof have the same name. With the changes of prana we have a corresponding

change in the other functions of life. The lower negative chakra contains the principal seats of some

of the other manifestations of life. This apana is located in the long intestine, samana in the navel, and so on.

Also, udana is located in

the throat; vyana all over the

body. Udana causes

belching; kurma in the eyes

causes them to shut and open; krikila in the stomach causes hunger. In short, proceeding from

the four petals of the heart we have an entire network of these blood vessels.

There are two sets of these blood vessels side by side in every part of

the body, connected by innumerable little channels, the capillaries.

We

read in the Prasnopnisat:

“From

the heart [ramify the] nadi. Of these

there are 101 principal ones (Pradhana nadi). Each of these branches into 100. Each of these again

into 72,000.”

Thus, there are 10,100 branch nadi, and 727,200,000 still smaller ones, or what are

called twignadi. The terminology

is imitated from a tree. There is the root in the heart. From these proceed

various stems. These ramify into branches, and these again into twig vessels; all

these nadi put together

are 727,210,201.

Now,

of these the one is the susumna; the rest are

divided half and half over the two halves of the body. So we read in

the Kathopnishat, 6th valli, 16th mantra:

“A hundred and one nadi are connected with the heart. Of these one passes

out into the head. Going out by that one becomes immortal. The others become

the cause in sending the life principle out of various other

states.”

This

one that goes to the head, remarks the commentator, is the susumna. The susumna then is that nadi whose nervous substratum or reservoir of force is

the spine. Of the remaining principal nadis, the Ida is the reservoir of the life force that works in

the left part of the body, having 50 principal nadi. So also has the right part of the body 50

principal nadi. These go on

dividing as above. The nadi of the third degree

become so minute as to be visible only by a microscope. The ramifications of

the susumna all over the

body serve during life to carry the prana from the positive to the negative portions of the body, and vice versa. In case of blood these are the modern

capillaries.

The

Vedantins, of course, take the heart to be the starting point of this

ramification. The Yogis, however, proceed from the navel. Thus in The Science of Breath we read:

“From the root in the navel proceed 72,000 nadi spreading all

over the body. There sleeps the goddess

Kundalini like a

serpent. From this center (the navel) ten nadi go upwards, ten downwards, and two and two

crookedly.”

The

number 72,000 is the result of their own peculiar reckoning. It matters little

which division we adopt if we understand the truth of the case.

Along

these nadi run the

various forces that form and keep up the physiological man. These channels gather up into

various parts of the body as centers of the various manifestations of prana. It is like water falling from a hill, gathering

into various lakes, each lake letting out several streams. These centers are:

(1) Hand power centers, (2) Foot power centers, (3)

Speech power centers, (4) Excretive power centers, (5) Generative

power centers, (6) Digestive and absorbing power centers, (7) Breathing power

centers, and (8) the five sense power centers.

Those

nadi that proceed to the outlets of

the body perform the most important functions of the body, and they are hence

said to be the ten principal ones in the whole system. These are:

(1)

Ghandari goes to the

left eye; (2) Hastijihiva goes to the

right eye; (3) Pasta goes to the

right ear; (4) Yashawani goes to the

left ear; (5) Alamhusha, or alammukha (as it is variously spelled in one ms.)

goes

to the mouth. This evidently is the alimentary canal; (6) Kuhu goes to the generative organs; (7) Shankini goes to the excretive organs; (8) Ida is the nadi that leads to the left nostril; (9) Pingala is the one that leads to the right

nostril. It appears that these names are given to these local nadi for the same reason that the pulmonary manifestation

of prana is known by the

same name; (10) Susumna has already been

explained in its various phases and manifestations.

There

are two more outlets of the body that receive their natural development in the

female: the breasts. It is quite possible that the nadi Danini, of which no specific mention has been

made, might go to one of these. Whatever it may be, the principle of the

division and classification is clear, and this is something

actually gained.

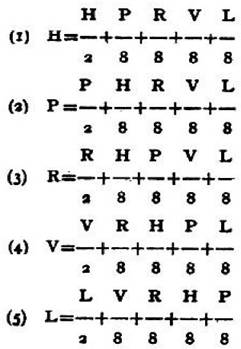

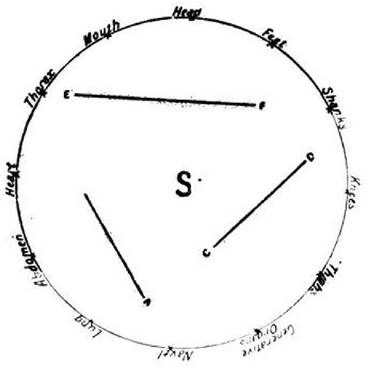

Centers of

moral and intellectual powers also exist in the system. Thus we read in the Vishramopnishat (The following figure will serve to

illustrate the translation):

“(1) While the mind

rests in the eastern portion (or petal), which is white in color, then it is

inclined towards patience, generosity, and reverence.

“(2) While the mind

rests in the southeastern portion, which is red in color, then it is inclined

towards sleep, torpor and evil inclination.

“(3) While the mind

rests in the southern portion, which is black in color, then it is inclined

towards anger, melancholy, and bad tendencies.

“(4) While the mind

rests in the southwestern portion, which is blue in color, then it is inclined

towards jealousy and cunning.

“(5) While the mind

rests in the western portion, which is brown in color, then it is inclined

towards smiles, amorousness, and jocoseness.

“(6) While the mind

rests in the northwestern portion, which is indigo in color, then it is

inclined towards anxiety, restless dissatisfaction, and apathy.

“(7) While the mind

rests in the northern portion, which is yellow in color, then it is inclined

towards love and enjoyment and adornment.

“(8) While the mind

rests in the northeastern portion, which is white in color, then it is inclined

towards pity, forgiveness, reflection, and religion.

“(9) While the mind

rests in the sandhi (conjunctions)

of these portions, then disease and confusion in body and home, and the mind

inclines towards the three humors.

“(10) While the mind

rests in the middle portion, which is violet in color, then Consciousness goes beyond the

qualities [three qualities of Maya] and it inclines toward Intelligence.”

When

any of these centers is in action the mind is conscious of the same sort of

feelings, and inclines towards them. Mesmeric passes serve only to excite these

centers.

These

centers are located in the head as well as in the chest, and also in the

abdominal region and the loins, etc.

It is these centers, together with the heart itself, that

bear the name of padma or kamala (lotus). Some of these are large, some

small, some very small. A tantric lotus is the type of a vegetable organism, a

root with various branches. These centers are the reservoirs of various powers,

and hence the roots of the padma; the nadi ramifying these centers are their various

branches.

The

nervous plexus of the modern anatomists coincide with these centers. From what

has been said above it will appear that the centers are constituted by

blood vessels. But the only difference between the nerves and the blood vessels

is the difference between the vehicles of the positive and negative prana. The nerves are the positive, and the blood

vessels are the negative system of the body. Wherever there are

nerves there are corresponding blood vessels. Both of them are indiscriminately

called nadi. One set has

for its center the lotus of the heart, the other the thousandpetalled lotus of

the brain. The system of blood vessels is an exact picture of the nervous

system; it is, in fact, only its shadow. Like the heart, the

brain has its upper and lower divisions the cerebrum and the cerebellum and

its right and

left divisions as well. The nerves going to very part of the body and

coming back from thence together with those going to

the upper and lower portions correspond to the four petals of the heart. This

system, too, has as many centers of energy as the former. Both

these centers coincide in position. They are, in fact, the same: the nervous

plexuses and ganglia of modern anatomy. Thus, in my opinion, the tantric padma are not only

the centers of nervous power the positive northern prana but

necessarily of the negative prana as well.

The translation of the Science of Breath that is now presented

to the reader has two sections enumerating the various actions

that are to be done during the flow of the positive and negative breath. They show nothing more than what can in some cases be very easily

verified, that certain actions are better done by

positive energy, and others by negative energy. The taking in of chemicals and

their changes are actions, as well as any others. Some of the

chemicals are better assimilated by the negative for example,

milk and other fatty substances), others by the positive Prana (other food,

that which is digested in the stomach). Some of our sensations

produce more lasting effects upon the negative, others upon the positive prana.

Prana has now

arranged the gross matter in the womb into the nervous and blood vessel

systems. The Prana, as has been seen, is made of the five

tatwa, and the nadi serve only as lines for tatwic currents

to run on. The centers of power noticed above are centers

of tatwic power. The tatwic centers in the right part of the body

are solar, and those in the left are lunar. Both these solar and lunar centers

are of five descriptions. Their kind is determined by what are

called the nervous ganglia. The semilunar ganglia are the

reservoirs of the apas tatwa. Similarly, we have the reservoirs of

the other forces. From these central reservoirs the tatwic

currents run over the same lines, and do the various actions allotted to them in physiological anatomy.

Everything in the human body that has more less of the

cohesive resistance is made up of the prithivi tatwa. But in this the various tatwas work imprinting

differing qualities upon the various parts of the body.

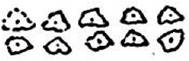

The vayu

tatwa, among others, performs the functions of giving

birth to, and nourishing the skin; the positive gives us the positive, and the

negative the negative skin. Each of these has five layers:

(1) Pure vayu, (2) Vayuagni, (3) Vayuprithivi, (4) Vayuapas, (5) Vayuakasa. These five classes

of cells have the following figures:

(1) Pure Vayu ~ This is the complete sphere of the Vayu:

(2)

VayuAgni ~ The triangle is superposed over the sphere, and the cells

have something like the following shape:

(3)

VayuPrithivi ~ This is the result of the superposition of the

quadrangular Prithivi over the spherical Vayu:

![]()

(4) VayuApas ~ Something like an ellipse, the semimoon

superposed over the sphere:

(5) VayuAkasa ~ The sphere flattened by the superposition

of the circle and dotted:

A microscopic

examination of the skin will show that the cells of the skin have this

appearance.

Similarly,

bone, muscle and fat are given birth to by the prithivi, the agni, and the apas. Akasa appears in various

positions. Wherever there is any room for any substance, there is akasa. The blood is a mixture of nutritive substances

kept in the fluidic state by the apas tatwa of Prana.

It

is thus seen that while Terrestrial Prana is an exact manifestation of the

Solar Prana, the human manifestation is an exact manifestation of either. The

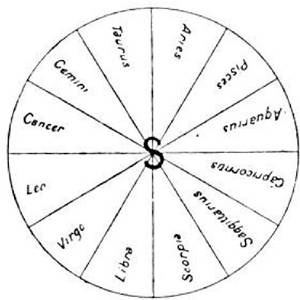

microcosm is an exact picture of the macrocosm. The four petals of the lotus of

the heart branch really into twelve nadi (K, Kh, g, gn, n, K’, Kh’, j, jh, n, t, the).

Similarly the brain has twelve pairs of nerves. These are the twelve signs of

the Zodiac, both in their positive and negative phases. In every sign the sun

rises 31 times. Therefore we have 31 pairs of nerves. Instead of pairs, we

speak in the language of the Tantras of a chakra (disk or circle). Wherever these 31 chakra

connect with the 12 pairs (chakras) of nerves in the brain, pass throughout the

body, we have running side by side the blood vessels proceeding from the 12 nadis

of the heart. The only difference between the spinal and cardiac chakras is that

the former lie crosswise, while the latter lie lengthwise in the body. The

sympathetic chords consist of lines of tatwic centers: the padma or kamal. These centers

lie on all the 31 chakra noticed above. Thus from the two centers of work, the

brain and the heart, the signs of the Zodiac in their positive and negative aspects

a system of nadi branch off.

The

nadi from either center run into one another so much that one set is found

always side by side with the other. The 31 chakra are various tatwic centers;

one set is positive, and the other is negative. The former owe

allegiance to the brain, with which they are connected by the sympathetic

chords; the latter owe allegiance to the heart, with which they have various

connections. This double system is called Pingala on the right side, and Ida on

the left. The ganglia of the apas centers are semilunar, those of the taijas, the

vayu, the prithivi, and the akasa respectively triangular, spherical,

quadrangular, and circular. Those of the composite tatwa have composite

figures. Each tatwic center has ganglia of all the tatwa

surrounding it.

Prana moves in this

system of nadi. As the sun

passes into the sign of Aries in the Macrocosm, the Prana passes into the corresponding nadi (nerves) of the brain. From thence it descends

every day towards the spine. With the rise of the sun it descends into the first

spinal chakra towards the

right. It thus passes into the Pingala. It moves along the nerves of the right side, at the

same time passing little by little into the blood vessels. Up to noon of every day

the strength of this Prana is greater in

the nervous chakra than in the venous. At noon they become of equal strength.

In the evening (with sunset), the Prana with its entire strength has passed into the blood

vessels. From thence it gathers up into the heart, the negative southern center.

Then it spreads into the left side blood vessels, gradually passing into the

nerves. At midnight the strength is equalized; in the morning (pratasandhia) the prana is just in the spine; from thence it

begins to travel along the second chakra. This is the course of the solar current of prana. The moon gives birth to other minor currents. The

moon moves 12 odd times more

than

the sun. Therefore, while the sun passes over one chakra (i.e., during 60 ghari day and night), the moon passes

over 12 odd chakra. Therefore we

have 12 odd changes of prana during 24

hours. Suppose the moon too begins in Aries; she begins like the sun in

the first chakra, and takes 58

min. 4 sec. in reaching the spine to the heart, and as many minutes from

the heart back to the spine.

Both

these prana move in their

respective course along the tatwic centers. Either of them is present at any

one time all over the same class of tatwic centers, in any one part of the

body. It manifests itself first in the vayu centers, then in the taijas, thirdly in the prithivi, and fourthly in the apas centers. Akasa comes after each, and immediately precedes the susumna. As the lunar current passes from the

spine towards the right, the breath comes out of the right nostril, and as long

as the current of Prana

remains

in the back part of the body, the tatwa changes from the vayu to the apas. As the current passes into the front part of the

right half, the tatwa changes back

from the apas to the vayu. As the prana passes into the heart, the breath is

not felt at all in the nose. As it proceeds from the heart to the left, the breath begins

to flow out of the left nostril, and as long as it is in the front part of the

body, the tatwa change from the

vayu to the apas. They change back again a before, until the prana reaches the spine, when we have the akasa of susumna. Such is the even change of prana that we have in the state of perfect health.

The impulse that has been given to the localized prana by the sun and moon forces that give active

power and existence to its prototype Prana, makes it work in the same way forever and ever. The working of

the human free will and other forces change the nature of the local prana, and individualize

it in such a way as to render it distinguishable from the universal Terrestrial

and Ecliptical prana. With the

varying nature of prana, the order of the tatwa and the positive and negative currents

may