The Terminology of the Vedas

The writings of Pandit Gurudatta on The Terminology of the Vedas provide a rich and intricate exploration of the philosophical depth within Vedic literature. Gurudatta’s work, composed in the early 20th century, serves as both a critique of prevailing interpretative methodologies and an advocacy for returning to ancient sources and principles for a more accurate understanding of these sacred texts. In this chapter, we delve into the core themes and observations of Gurudatta’s treatise, highlighting its relevance for contemporary Vedic studies and its challenge to established Western interpretations.

1. Introduction to Shabda and Its Philosophical Importance

Gurudatta frames Shabda (sound or inspired speech) as a foundational concept in Sanskrit literature, with its influence spanning multiple disciplines, including grammar, etymology, philology, and metaphysics. He emphasizes that this concept holds a central position not only in linguistic studies but also in philosophical inquiries, as evidenced by Jaimini’s Mimansa. This text dedicates significant attention to Shabda, highlighting its integral role in understanding Vedic language and thought.

2. Challenges in Interpreting Vedic Terminology

Gurudatta critiques previous methods of interpreting Vedic texts, asserting that they rely too heavily on preconceived notions rather than objective and rational analysis. He identifies three primary interpretative approaches:

-

Mythological Method: This method views the Vedas as mythic constructs rooted in early human attempts to personify natural forces. Gurudatta critiques this approach as speculative and reductionist.

-

Antiquarian (Historical) Method: Focused on contemporaneous literature and cultural context, this method provides valuable insights but demands rigorous attention to linguistic evolution.

-

Contemporary Method: Attempts to discern the chronology of Sanskrit texts through linguistic and stylistic evolution, though often fraught with inconsistencies.

3. Criticism of the Mythological Method

Gurudatta argues that the mythological method oversimplifies the Vedas, reducing them to imaginative constructs of primitive societies. He asserts that such interpretations fail to capture the philosophical richness of the texts, suggesting instead that mythology might represent a degeneration of earlier religious or philosophical truths.

4. Philosophy vs. Mythology

A central argument in Gurudatta’s work is the precedence of philosophy over mythology in Indian intellectual traditions. He contrasts mythology, which symbolizes human thought in concrete terms, with philosophy, which abstracts ultimate truths. This contrast undermines the mythological method’s claim to fully explain the Vedas. Gurudatta emphasizes that the Upanishads and Darshanas, which are deeply philosophical, chronologically precede the Puranas, the embodiment of Indian mythological literature.

5. Ancient vs. Modern Interpretations

Gurudatta critiques modern scholars for relying on late commentaries by figures like Sayana and Mahidhara, which he views as distorting the original meanings of Vedic terms. He advocates revisiting older sources such as the Nirukta, Shatapatha Brahmana, and Upanishads, which he deems more accurate and reflective of the Vedas’ philosophical foundations.

6. Classification of Words in Sanskrit

To support his critique, Gurudatta identifies three types of words in Sanskrit:

-

Yaugika: Words with derived meanings based on their root structures and affixes, embodying intellectual and philosophical depth.

-

Rurhi: Words with arbitrary or conventional meanings.

-

Yoga-Rurhi: Compound words that denote relationships or phenomena.

Gurudatta asserts that Vedic terms are predominantly yaugika, reflecting their intellectual and symbolic sophistication, as affirmed by ancient texts like the Mahabhashya.

7. Historical Missteps in Modern Interpretation

Modern scholars are criticized for misapplying antiquarian methods and overly relying on late-period commentaries. Gurudatta contends that these approaches lead to “unintelligible and absurd” interpretations, neglecting the guidance offered by ancient texts. He underscores the importance of contextualizing Vedic language within its original intellectual and cultural milieu.

8. Monotheistic and Philosophical Nature of the Vedas

Contrary to the perception of the Vedas as polytheistic or mythological, Gurudatta highlights their monotheistic and philosophical insights. He points to the Upanishads as evidence of the profound theological and philosophical framework inherent in Vedic texts, which modern interpretations often fail to recognize.

Key Observations and Themes

-

Centrality of Shabda: The philosophical significance of Shabda underscores the profound intellectual activity behind Vedic literature.

-

Critique of Western Methods: Gurudatta’s criticisms of Western scholars challenge their reliance on late commentaries and mythological interpretations.

-

Call for Rational and Historical Analysis: By advocating for a return to ancient sources and principles, Gurudatta emphasizes the importance of rigorous, historically grounded methods.

Conclusion

Gurudatta’s The Terminology of the Vedas provides a powerful critique of both ancient and modern interpretative methods, championing the philosophical and intellectual richness of Vedic literature. His arguments underscore the necessity of moving beyond mythological reductions and engaging deeply with the philosophical underpinnings of these ancient texts. As a foundational chapter in the study of early Vedic philosophy, his work invites readers to reconsider long-held assumptions and to explore the profound depths of India’s intellectual heritage.

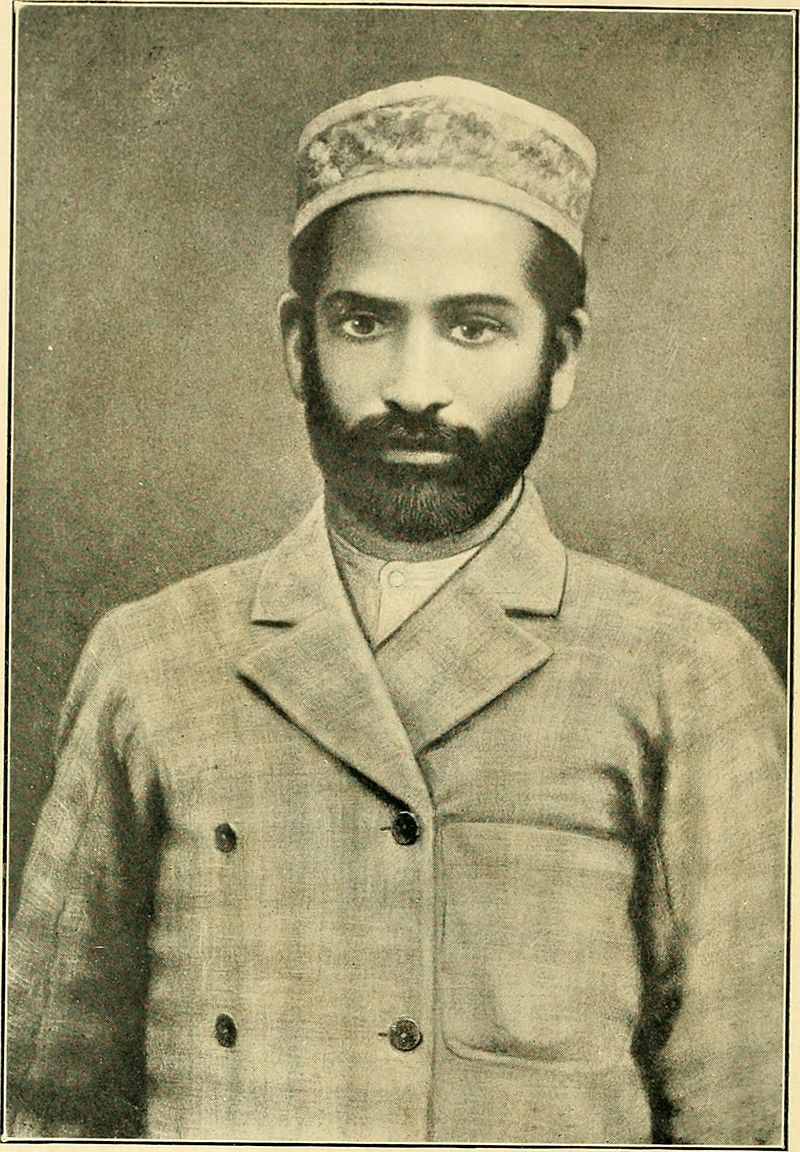

Dedicated to the Memory of

The Only Vedic Scholar

of his time

Swami Dayananda Saraswati,

by

His Sincere and Devoted

Admirer, the Author

Guru Datta Vidyarthi,

Lahore, 1.6.1888

***

The Terminology of the Vedas

THE question of the origin, nature and eternity of Shabda-human articulate and inspired speech-has been a very important question in Samskrita literature. The highly philosophical character of this question cannot be doubted, but the peculiar characteristic, which attracts the attention of every Samskrita scholar is, the all-pervading nature of the influence it exerts on other departments of human knowledge. It is not only the Nairukta and the Vaiyakaranas, the grammarians, etymologists and philologists, of ancient Samskrita times, that take up this question; but even the acute and subtle philosopher – the last and the best Samskrita metaphysician – the disciple of the learned Vyasa – the founder of one of the six schools of philosophy – the religious aphorist Jaimini cannot isolate the treatment of his subject from the influence of this question. He runs in the very beginning of his Mimamsa ( dissertation ) into this question and assigns a very considerable part (proportionately) of his treatise to the elucidation of this question. It is not difficult for a reader of the modern philology, well-versed in discussion on onomatopoeian (the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it (such as buzz, hiss) and other theories of human speech, to perceive the amount of wrangling which such questions give rise to. We have mentioned the position assigned to this question in Samskrita literature not so much with a view to put an end to all this wrangling, which, perhaps, is unavoidable, but with a view to take up, in a brief way, another and a more practical question involved therein, i.e., the question of the interpretation of Vedic terminology.

Up to this time all the plans that have been adopted for the interpretation of Vedic terminology have been based on some pre-conceived notions. The philosophy of the subject requires that, these pre-conceived notions should be carefully examined, studied and pruned of the extraneous matter liable to introduce error, whereas new and more rational methods should be sought after and interposed – methods such as may throw further light upon the subject. To examine, then, the various methods that have up to this time been pursucd. Briefly speaking, they are three in number, and may, for want of better denomination, he called the Mythological, Antiquarian and Contemporary method.

Firstly, the Mythological method. This method interprets the Vedas as myths, as an embodiment of simple natural truths in the imaginative language of religious fiction, as a symbolic representation of the actual in the ideal, as an imbedding of primitive truth in the super-incumbent strata of non-essential show and ceremony. Now, in so far as this concretion of thought in mythological network goes, it assumes a comparatively rude and simple stage of human life and experience. From this basis of a primitive savage-state it gradually evolves the ideas of God and religion, which no sooner done than mythic period ends. It further argues thus: – In the ruder stage of civilization, when laws of nature are little known and but very little understood, analogy plays a most important part in the performance of intellectual functions of man. The slightest semblance, or vestige of semblance, is euongh to justify the exercise of analogy. The most palpable of the forces of nature impress the human mind, in such a period of rude beginnings of human experience, by motions mainly. The wind blowing, the fire burning, a stone falling, or a fruit dropping, affects the senses essentially as moving. Now throughout the range of conscious exerrtion of muscular power, will precedes motion, and, since even the most grotesque experience of a savage in this world assumes this knowledge it is no great stretch of intellectual power to argue that these natural forces also to which the sensible motions are due, are endowed with the faculty of will. The personification of the forces of nature being thus effected, their deification soon follows.

Continue reading:

https://beezone.com/current/guru-pandit-datta-vidyarthi.html