Originally published in

Laughing Man magazine, Vol 7, NBR 1

1987

by Carolyn Lee

In the house of Mary and Mrth (painting by Tintoretto, 16th century

Speaking to devotees on December 16,1975, Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda remarked, “There is only one process that makes a difference, the process of distraction in God. That is what the practice of Spiritual life is. It is the only thing worth doing. Everything else is a hellish evolution of desires and complications of form. There is only one way to be saved, and that is to love God to the point of absolute distraction.”

It was through their distracted love for him that Krishna attracted the gopis beyond their conventional destinies. The cowherd maidens were madly attracted by the Radiance of the ) young Adept, and they wandered after him, forgetting cattle and husbands. The same paradigm of devotion, witnessed in the relationship between an Adept and the female devotees surrounding him, appears throughout the religious traditions. This devotional relationship is exemplified in the ancient Vedic custom of t’ahmavwaha, in which young women dedicated themselves in marriage to a God-Man as a Spiritual service performed for the sake of enlightening others. In modern times, this practice was revived by Sri Upasani Baba Maharaj of Sakuri (1870-1941), who “married” over two dozen women who formed the foundation of his ashram, the Kanya Kumari Sthan.

Likewise, in the Company of Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda there has generally been a small group of women who have served his physical environment and human form most personally. And, while the practice of all devotees is based on the ecstatic relationship to the Adept, these women have epitomized that devotional relationship to him. Through his Spiritual service to these women, Heart-Master Da has developed aspects of his Wisdom-Teaching that serve everyone, men and women alike. Thus, their particular relationship to the True Heart-Master not only serves him personally, but also, by extension, all devotees.

In the following article, Carolyn Lee explores Jesus of Nazareth’s relationship to some of the women “distracted” in love by this fiery Teacher and loving Master who attracted people of many faiths beyond themselves.

Elizabeth, Mother of John the Baptist

Beginning our discussion chronologically, the first woman associated with the life of Jesus was not his mother, Mary, but Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, who is described as a kinswoman of Mary. The first chapter of Luke’s Gospel recounts Elizabeth’s conception at an advanced age and her gratitude to God that she would no longer be barren. The event of her pregnancy is paired with the annunciation to Mary and the two women come together to rejoice in the Divine blessing they have mutually received. Elizabeth’s unborn son, destined to be the forerunner of Jesus, is said to leap in her womb, filling Elizabeth with the grace of recognition of the one her cousin is to bear.

Christian art provides many tender renditions of Elizabeth and Mary embracing, enveloped in the mystery of their bodily intimacy with God. Like all the infancy narratives in the Gospels, Elizabeth’s story points to the significance of the birth of Jesus, rather than to the facts of the event.

Mary, the Mother of Jesus

Rogier van der Weyden, Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin, 1435–40

As a real historical figure, Mary is very difficult to reach. Within a couple of centuries of the life of Jesus she had passed into myth as Theotokos, the God-bearer, and was worshipped as Queen of Heaven. New Testament references to her after the birth narratives are relatively few but nonetheless striking for that. The first two references, which precede the public ministry of Jesus, are probably legendary, but they serve to indicate a tension between Jesus and his mother regarding his growing consciousness of a special mission.

In the first story, Jesus, at the age of twelve, accompanies his family on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem at Passover time. Unbeknownst to his relatives, Jesus stays behind, taking the opportunity to debate the Hebrew Law with the leading rabbis at the temple. During their homeward journey his parents notice his absence and return to Jerusalem anxiously seeking him. When he is discovered, his mother reproaches him for the distress he has caused them. She receives the famous reply: “Why were you looking for me? Did you not know that I must be busy with my Father’s affairs?” Mary, we are told, did not understand what he meant, but “she stored up all these things in her heart”.

By the time Jesus reached adulthood Mary must have been well aware of remarkable powers in her son. The story of the wedding at Cana in Galilee, at which Jesus and his mother are guests, may derive from a combination of Old Testament material and Hellenistic miracle tales about wine. In the Gospel account (John 2:1-10) Mary appeals to her son when the wine runs out, apparently in the hope that he will use his powers to save their hosts embarrassment. Jesus replies, “Woman, why turn to me? My hour has not come yet.” But in spite of this rebuff to his mother, Jesus is said to have instructed the servants to fill the water jars with water. When they draw off the liquid they find it is wine. The dialogue with Mary suggests that Jesus acts for his own mysterious reasons rather then in direct response to his mother, who, perhaps, liked to enjoy reflected glory from the prowess of her son.

Apart from these stories of dubious historicity a much more stark encounter is described in two Gospels (Mark 3:31-35 and Luke 8:19-21), which is anything but flattering to Mary. Modern commentators agree that it is not the sort of material likely to have been invented by the early Church. Jesus is teaching one day when his mother and brothers arrive wishing to see him. They are obliged to send a message to him as they cannot reach him for the crowd. When he receives the message, Jesus says to those sitting around him, “Who are my mother and my brothers? Here are my mother and my brothers . . . my mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and put it into practice.” A similar moment occurs when a woman in a crowd around Jesus cries out, “Happy the womb that bore you and the breasts you sucked!” (Luke 11:27-28). Jesus replies, “Still happier those who hear the word of God and keep it!”

These incidents add up to a Divine play between Jesus and his mother, the purpose of which is to serve her Spiritual recognition of him. Contrary to the weight of Christian tradition, the Gospels indicate that Jesus did not regard as important the fact that Mary was his natural mother. He was inviting her to pass through a profound crisis that involved her surrender of the role of mother to assume that of disciple. The Gospel of John suggests that she did pass through this transformation. Witherington (pp. 94-95) holds the view that the beloved disciple saw Mary as a devotee, one whom Jesus himself had acknowledged in the family of faith. Independent support for this conclusion appears in the Acts of the Apostles (1:14), where Mary is mentioned as a member of the devotional community that gathered together after the Ascension of Jesus to prepare for the promised baptism of the Holy Spirit.

Mary’s path was perhaps uniquely difficult.

The other women who followed Jesus were not impeded by a prior natural relationship: they had the advantage of a spontaneous response to the shock of his appearance in their lives.

The Woman at the Well

The shock of sudden encounter with the Adept comes through in the story of Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well of Sichar. The account occurs in John 4:5-26 and describes Jesus, wearied by a long journey, sitting by the well while his disciples go to the town to buy food. A woman comes to draw water, and he asks her for a drink, much to the woman’s astonishment, for “Jews … do not associate with Samaritans”. The dialogue that follows is a play on the exoteric and esoteric meanings of water. Jesus is using water to expound his hidden teaching on the Spirit. John 4:10:

“If you only knew what God is offering and who it is that is saying to you: Give me a drink, you would have been the one to ask, and he would have given you living water.”

“You have no bucket, sir,” she answered, “and the well is deep: how could you get this living water?” Jesus replied, “Whoever drinks this water will get thirsty again; but anyone who drinks the water that I shall give will never be thirsty again: the water that I shall give will turn into a spring inside him, welling up to eternal life.’’

“Sir,” said the woman, “give me some of that water, so that I may never get thirsty and never have to come here again to draw water.”1

When Jesus shows that he knows the character of her life (little better than a prostitute from a Jewish point of view) the woman declares him to be a prophet and questions him on the true place of worship, an issue of difference between Jews and Samaritans. Jesus responds that a revelation of the real nature of God and of worship is now being made:

“God is spirit, and those who worship must worship in spirit and truth.”

The woman said to him, “I know that Messiah—that is, Christ—is coming; and when he comes he will tell us everything.”

“1 who am speaking to you,” said Jesus, ” I am he.”

The woman then left her water jar and returned to the town, confessing her experience and asking, “I wonder if he is the Christ?” The Gospel account says that many Samaritans came to Jesus and invited him to stay in their town, with the result that many more put their faith in him and became disciples.

Many New Testament scholars have pondered this story, in itself a beautiful and skillful literary piece, trying to discover whether it is merely a theological composition or whether it might have a basis in fact. After weighing the .evidence, Witherington (p. 58) concludes that it is quite likely that a real encounter lies behind it. It is consistent with the broad witness of the Gospels, which show Jesus’ teaching making its point again and again among the unsophisticated, the unimportant, the sick, and the socially unacceptable. Jesus speaks of prostitutes, tax collectors, and sinners entering the kingdom of God ahead of the pharisees, the custodians of the religious establishment (Matthew 21:31). He also speaks of the secrets of the kingdom being hidden from the “learned and the clever” and revealed to “mere children” (Luke 10:21). The Jewish women of Jesus’ day were children in this sense. They were not instructed in the Law nor allowed to become students of rabbis. Therefore it is nothing short of iconoclastic that John’s Gospel should connect Jesus’ secret Spirit-teaching with an unlettered and sinful woman who was not even a Jew.

- This and all other biblical quotations are taken from The Jerusalem Bible, Reader’s Edition (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1968).

Women Healed by Jesus

As a healer,Jesus obviously responded to both men and women, but Luke’s Gospel makes a specific connection between healing and discipleship in the case of women. Luke 8: 1-3 reads

. . . he made his way through towns and villages preaching, and proclaiming the Good News of the kingdom of God. With him went the Twelve, as well as certain women who had been cured of evil spirits and ailments: Mary surnamed the Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza, Susanna, and several others who provided for them out of their own resources.

A number of stories in the Gospels describe Jesus healing women, although no descriptions survive of the healing incidents in the cases mentioned above. A particularly striking story is that of a woman with a hemorrhage who makes her way to Jesus through a crowd pressing around him. She reaches out and touches the hem of his garment in the hope of receiving relief from her twelve-year affliction (Matthew 9:20-22; Mark 5:25-34; Luke 8:43-48). She does not speak to Jesus but wishes to remain unnoticed, presumably because of embarrassment and because it was an offense for a woman in an unclean condition to touch a rabbi – thereby rendering him also unclean, according to the Law. Jesus heals her spontaneously and then draws her out from the crowd, blessing her faith.

If Luke’s report is correct, there were “many” such women who were moved, after receiving healing, to abandon their ordinary responsibilities and the protection of their homes to follow an itinerant teacher in this way, thus exposing themselves to scandal and social rejection. Nor were these women necessarily already outcasts who had nothing further to lose. The mention of the wife of Chuza, King Herod’s steward, and the remark that the women offered material support in their ministry to Jesus shows that ladies of substance and status also made the sacrifice of discipleship. These women must have loved Jesus with a love that moved them beyond every ordinary concern, leaving them with no choice but to follow their hearts. This is not to say that the men disciples who left fishing businesses (Peter and Andrew, James and John) and a government job (Matthew, the tax collector) were not also heart-smitten. The particular role of healing in Jesus’ calling of women is interesting, because it implies a transformation in the body-mind as the basis of conversion of the heart. Feminine wisdom and intuition are natively rooted in the body and its feelings, the natural seat of a woman’s love-response and recognition of the Divine. Thus, the traditions often show female disciples of Spiritual Masters living their sadhana, or Spiritual practice, in intimate bodily service to the Adept.

The Anointing Stories

Women Healed by Jesus

The bodily dimension of worship and service comes through strongly in several stories describing a woman anointing Jesus with costly perfume as he sits at a banquet. The accounts in Mark and John are closely related and apparently describe the same event. Luke’s narrative has distinctive features suggesting that the anointing element has been introduced into a different situation, either deliberately by the Gospel writer, or as a result of a mixing at the stage of oral transmission (Witherington, p. 111).

In Mark’s account, an unnamed woman pours a flask of ointment over the head of Jesus, while in John’s story Mary of Bethany kisses his feet and anoints them with perfume, wiping them with her hair. The reaction of the onlookers (Pharisees and male disciples) in both accounts is one of embarrassment and righteous indignation. Mark 14:4-6:

Some who were there said to one another indignantly, “Why this waste of ointment? Ointment like this could have been sold for over three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor”; and they were angry with her. But Jesus said, “Leave her alone. Why are you upsetting her? What she has done for me is one of the good works. You have the poor with you always, and you can be kind to them whenever -you wish, but you will not always have me. She has done what was in her power to do: she has anointed my body beforehand for its burial. I tell you solemnly, wherever throughout all the – world the Good News is proclaimed, what she has done will be told also, in remembrance of her.’’

The formal anointing of rabbis’ feet apparently occurred among the Jews, and Greek men are known to have had their feet smeared with ointment by a female slave (Witherington, p. 113). It is the extravagance in the quantity and quality of the ointment, “the scent of which filled the whole house” (John 12:3), and the engagement of the whole body in wiping Jesus’ feet with her hair that made the woman’s action scandalous. She was literally ecstatic, outside or beyond her normal condition, transported by love and devotion. Jesus, it seems, saw the woman’s action not merely in personal, emotional terms but as a sacramental service to his body. Read from the point of view of some oriental traditions, which emphasize Guru-devotion through bodily worship of the feet or padukas (ceremonial sandals) of the Spiritual Master, this story stands as a paradigm of submission to and recognition of the Divine in human form.

Some Christian interpretations of the story also express this insight: “… the mystery of his incarnation may be understood by his feet in themselves: the means by which the divine touched the earth by taking flesh” (Homil. xxxiii, In Evangelio, Gregory the Great, Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 76, col. 1242).

The anointing story in Luke presents the woman as a well-known prostitute, weeping over the feet of Jesus, wiping them with her hair, and then anointing them. A conflation of stories and traditions does seem to be present here. It may be that some woman, moved to conversion by her attraction to Jesus, became a disciple and later performed an anointing. Christian tradition from an early date took the view that this prostitute who anointed Jesus was to be identified with Mary Magdalene, his principal female disciple, although there is no Gospel authority for this (see below). The most interesting aspect of the story as it occurs in Luke are Jesus’ remarks to his host, Simon the Pharisee, who doubts that Jesus can be a prophet because he has allowed the woman to touch him (Luke 7:44-48):

“Simon,” he said, “you see this woman? I came into your house, andyou poured no water over my feet, but she has poured out her tears over my feet and wiped them away with her hair. You gave me no kiss, but she has been covering my feet with kisses ever since I came in. You did not anoint my head with oil, but she has anointed my feet with ointment. For this reason I tell you that- her sins, her many sins, must have been forgiven her, or she would not have shown such great love. It is the man who is forgiven little who.shows little love.”

The woman is already forgiven because her heart is broken open. She is careless of impropriety or loss of face because she is lost in love and already enjoys the Divine embrace. The Pharisee, on the other hand, is still closed to what Jesus has to offer.

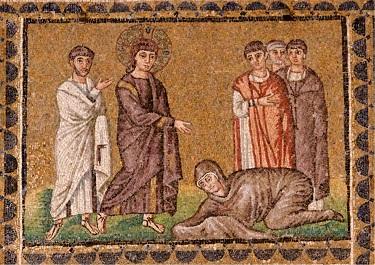

Martha and Mary of Bethany

The record of Jesus’ relationship with the two sisters of Bethany provides a rare glimpse of Jesus in active relationship to two of his women disciples. These women, it would appear, did not travel with him but lived at home with their brother Lazarus, offering hospitality to Jesus from time to time. Martha was probably the eider, as Luke describes her “receiving Jesus into her house”. In any case the stories consistently show Martha to be the active sister, taking charge and showing initiative. Mary’s demeanour, on the other hand, is quiet and contemplative.

The famous, even proverbial, occasion mentioned by Luke has Jesus teaching in their house with Mary sitting at his feet while Martha is “distracted with all the serving”. Martha feels increasing anger that her sister is not helping her and finally explodes, “Lord, do you not care that my sister is leaving me to do the serving all by myself? Please tell her to help me.” (Luke 10:40) Martha is undone by a few words from Jesus, who dismisses her anxiety and agitation, indicating that Mary is doing the only necessary thing, that is to say, submitting all her attention to him. Luke 10:41-42:

“Martha, Martha,” he said, “you worry and fret about so many things, and yet few are needed, indeed only one. It is Mary who has chosen the better part; it is not to be taken from her.”

The other story of the sisters concerns the illness of their brother Lazarus and their urgent message to Jesus to come and save his life. By the time Jesus arrives, however, Lazarus is dead and buried. According to the account Jesus raises him from the dead, but it is John’s account of his play with the sisters prior to this event that is most pertinent here. Jesus is testing them. He delays coming. Martha goes out to meet him when he is still some way from their village, blurting out her grief, distress, and even anger that he did not come sooner. In the exchange that follows Jesus probes her recognition of him and Martha finally responds, “I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, the One who was to come into this world.” With Mary the encounter has a different quality. When Jesus sends for her she collapses in grief at his feet, and although her words are the same as Martha’s (“Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died”), Jesus’ response is different. Mary’s heart-connection to him is such that he weeps. Amid intense emotion he asks to be taken to the tomb and that the tomb be unsealed. Martha provides the entirely human and comic line, “Lord, by now he will smell; this is the fourth day.”

Martha is amusing, and also instructive, because she is so true to life. Her energy and generosity are attractive. At the same time there is an impulsiveness in her vitality, which tends to cloud a deeper response, a response that certainly existed, since one of the few confessions of the nature of Jesus recorded in the Gospels is placed in her mouth. In the first story Jesus is not criticizing Martha’s desire to serve, but rather the agitation that is distracting her from the true significance of the occasion and preventing her Spiritual alignment to him. Mary’s virtue lies in that alignment. The message does not seem to be that Martha should do exactly as Mary does but that she should serve in the disposition of a devotee, rather than as a harried hostess. A reference to Martha serving at a banquet for Jesus and Lazarus after Lazarus is restored to life (John 12:2) shows Martha still in her serving role, but now, one imagines, with a new attitude, the peace of gratitude and devotion. Witherington (p. 112) points out that prosperous Jewish women of the time did not serve their guests personally but were expected to leave that to the servants. This means that Martha was literally assuming the role of servant as a way of expressing her love for Jesus. She was fulfilling his repeated injunction that his disciples must live as servants, following his own example.

Perhaps the most original commentary on Martha and Mary in the Christian tradition occurs in a sermon by Meister Eckhart, the great Dominican mystic and theologian (vernacular sermon eighty-six). Contrary to tradition, which lauded Mary above Martha as the perfect symbol of contemplation, Meister Eckhart praised Martha enthusiastically for the fact that she embraced life wholeheartedly while not lacking in devotion to Jesus: “What a wondrous involvement both outwardly and inwardly: understanding and being understood; seeing and being seen; holding and being held” (The Women Around Jesus, p. 29).

Mary, on the other hand, he regarded as one-sided, not yet mature. She has to learn to live and assume life-responsibilities rather than merely to listen passively. But whatever Mary may still have had to learn, the Gospel stories show her living a life of steady heart- remembrance of Jesus, while Martha is at a different stage, still phasing in and out of it.

The Women Who Went to the Tomb

All the Gospels associate female witnesses with the death of Jesus. Luke 23:28 describes lamenting women along the via crucis, the “daughters of Jerusalem” whom Jesus counseled to weep not for him but for their own loss, the loss of the Master. John’s Gospel (19:25-26) mentions women beside the cross (Mary, his mother, his mother’s sister, and Mary Magdalene), while the other records describe his women disciples standing at a distance (Matthew 27:55; Mark 15:40-41). Following the crucifixion there are three accounts of women at the burial in Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb (Matthew 27:61; Mark 15:47; Luke 23:55). According to Luke, they returned home afterward “and prepared spices and ointments” (23:56). Then, after the Sabbath observance, “early in the morning on the first day of the week”, all the Gospels describe women visiting the tomb, and, except for John, mention that they carried spices to anoint the body.

The notable absence of the leading men disciples during these events (except for St. John at the crucifixion) is striking. In view of the fact that men presumably wrote these records, it is safe to assume that the men really were hanging back, shocked, stunned, and afraid. As men, they had more to lose than the women in being identified with the teacher executed as a criminal. It is also true that the women had specific responsibility toward the dead body of Jesus. It was women’s work to prepare and anoint a corpse. While the Gospel accounts are terse, later Christian literature and commentary often imagines the women’s desolation in passionate and even romantic terms. They came to incarnate the undying myth of feminine grief at separation from the beloved, both human and Divine. This is especially true in the case of Mary Magdalene, to whom we will turn in a moment. What is impressive about the largely anonymous group of women who followed Jesus is their fidelity and endurance. Even after the worst had happened, they were still with Jesus, still serving his body.

Mary Maddalene

The Mary Magdalene of Christian tradition is a largely invented character combining three different persons. The only woman so named in the Gospels is the Mary of Magdala (a town on Lake Gennesereth) from whom Jesus cast out “seven demons” (Luke 8:2, see above), who stood by the cross, and who met Jesus on Easter day beside his empty tomb. The other female figures were absorbed under her name through a quaint economy in the medieval imagination. Thus, Mary of Bethany, because of her closeness to Jesus, was considered to be the same person as Mary Magdalene, and the anonymous prostitute who wept over the feet of Jesus and anointed them (Luke 7:36-50) was held to be Mary Magdalene as well because of the connection via Mary of Bethany, who carries out an anointing in John 12:1-8.

Mary Magdalene’s relationship to Jesus has been described in various ways, although it is generally assumed that in actual expression it was wholly platonic. Before considering other possibilities, it is important to look at her principal (though perhaps apocryphal) appearance in the New Testament, that is, her experiences on Easter Day, which are described most fully in John 20:1-18. The other women bearing ointments and spices do not figure in John, which tells of Mary coming to the tomb alone before dawn:

She saw that the stone had been moved away from the tomb and came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved. “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, ’’she said, “and we don’t know where they have put him.”

So Peter set out with the other disciple to go to the tomb. . . . Simon Peter. . . went right into the tomb. . . . Then the other disciple . . . also went in; he saw and he believed. . . . The disciples then went home again.

Meanwhile Mary stayed outside near the tomb, weeping. Then, still weeping, she stooped to look inside, and saw two angels in white sitting where the body of Jesus had been. . . . They said, “Woman, why are you weeping?” “They have taken my Lord away,” she replied, “and 1 don’t know where they have put him.” As she said this she turned around and saw Jesus standing there, though she did not recognize him. Jesus said, “Woman, why are you weeping? Who are you looking for?” Supposing him to be the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have taken him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will go and remove him.” Jesus said, “Mary!”She knew him then and said to him in Hebrew, “Rabbunil”— which means Master. Jesus said to her, “Do not cling to me, because I have not yet ascended to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God. “So Mary of Magdala went and told the disciples that she had seen the Lord and that he had said these things to her.

Mary Magdalene behaves as a woman widowed. Her Lord is her life. She has nothing left to do or to defend. The men disciples come and go, but she remains without human or heavenly consolation. As Gregory the Great noted, there is a remarkable parallel between the story of Mary’s seeking and finding the risen Jesus and the Shulamite .woman in the “Song of Songs” who has been separated from her lover.

Another Patristic writer, Rabanus Maurus (ninth century) likens her to the royal bride in psalm 45 (46) and speculates that “Mary suffered as lovers are accustomed to suffer” and “mourned inestimably concerning the corporeal absence of her beloved lover” (Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 171, cols. 1485-6). In the Hindu tradition, the gopis of Sri Krishna are similarly crazed in ardent search for their absent lover.

Like her Spiritual sisters of many traditions, Mary Magdalene was enamored of the Divine in human form to the point of distraction. There is a sense in which all these feminine figures embody the Shakti force, the attractive goddess power, such that they inevitably draw their Lord back to them. And he comes, as it is said of the bridegroom in the “Song of Songs” (4:9), “wounded by love”.

But aside from the fascinating web of romantic and erotic mythology that can be wound around Mary Magdalene on the basis of John’s famous passage, if we were to assume that she points to at least one real woman who was the intimate friend and disciple of Jesus, what might the nature of their relationship have been? The question of a possible sexual relationship could not arise in orthodox Christian tradition from the time of St. Paul. Thus the passionate imagery that arose spontaneously in the minds of many Christian writers was automatically given a “spiritual” interpretation.

taneously in the minds of many Christian writers was automatically given a “spiritual” interpretation.

Possible exceptions are to be found in Gnostic Christian writings of the second century that were never accepted into the orthodox canon of the New Testament. As these documents probably date from less than one hundred years after the Gospel of John they deserve serious attention. In the so-called “Gospel of Mary”, Mary Magdalene’s senior position relative to the other women disciples is noted. The apostle Peter says to her: “Sister, we know that the Saviour loved you more than the rest of the women . . . tell us the words of the Saviour which you remember . . .” (John Dent, The Laughing Saviour, p. 127). In the “Gospel of Philip” she is twice described as the “consort” (koinonos) of Jesus.

The Gnostic documents are mainly concerned with Mary as the recipient of secret knowledge from Jesus and her prior place as a Spiritual initiate in his community. Nevertheless, in emphasizing her special relationship to him they support the testimony of John’s Gospel.

Most Christian writers are unaware of any tradition that could illumine how and why a Spiritual Master might actually engage the sexual dimension. Nevertheless there is a tradition, albeit an esoteric or secret one, of Enlightened Teachers practicing a form of tantric Yoga that involves sexual union with one or more of their women devotees. An example is Padmasambhava, a renowned Indian Buddhist Master who, with the aid of his consort and principal disciple Yeshe Tsogyal, spread the Dharma in Tibet in the eighth century. Some Adepts have actually established a permanent circle of tantric consorts, including Marpa the Translator and, in modern times, the Indian teacher Upasani Baba. Many such figures have remained celibate, depending on how they were spontaneously moved to teach in any given time and place. The precise nature of the relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene will never be known, but the nub of it remains instructive—the necessary transcendence (not the denial) of the body-mind in the true relationship to an Adept. This is the crux of Jesus’ message to Mary, which she is charged to carry to all his disciples.

John’s account implies that at the moment of recognition, Mary clasps the feet of Jesus or reaches out to embrace him. His response, “Do not cling to me”, shows that there is a lesson to be learned. Mary is still relating to Jesus in a limited, human way, desiring to keep and hold him on her own terms. As long as she persists in this she obstructs both the fulfillment of his mission and her own Spiritual growth. When he says, “I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God, and your God”, Jesus is calling her to release her passionate attachment to his physical form and learn to relate to him as Spirit.

Whatever the nature of Mary’s awakening on that momentous day, she was facing profound and unavoidable change. According to the Gospel accounts he was gone from sight permanently within weeks of the first Easter appearances. Elizabeth Moltmann speculates:

What does she have to say to us, this woman who was healed, who combines friendship and surrender, eros and agape? This woman who to the last clings to this earth and relationships on it? This woman who learns that resurrection means that she must not remain in this circle, but learn to be open towards a new community? The theology of Mary Magdalene has not yet been written. (The Women Around Jesus, p. 75)

Conclusion

If women are to be found time and again in special relationship to Spiritual Masters, the reason lies in their capacity for profound recognition of the Divine in human form. They, by nature, are more easily able to live the submission that is the necessary ground of Spiritual practice. Thus they become vital agencies for the Divine work. In a memorable passage in the Srimad Bhagavatam, the sages who have failed to recognize Lord Krishna make their confession:

We had heard it said everywhere that the exalted Lord Vishnu, who is Himself all that constitutes the Sacrifice—the time, the place, every one of the materials used . . . was incarnate among the Yadus; and yet, fools that we were, we did not know Him. But how blest we are in our wives! It is their devotion that has led us to firm faith in Hari [Krishna].2

Sri Upasani Baba spoke of the native Spiritual disposition of women as “daan”, or the giving of oneself as a gift to God, and he described his circle of women as “kanya kumaris” or “those who destroy illusion and lead others to the Supreme Reality”. He claimed that women could function as “Spiritual engines” capable of extending the reach of his Spiritual influence.

While Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda does not limit this quality to women, he has likewise spoken of the female nature in relation to Spiritual life. He has explained that “The male and female both need to awaken to the feminine action, which is self-transcendence, and fulfill it. In that case, both will also come into union with the male role or action (the creative spirit or subtle intelligence and generative power). Both need to restore the balance of the halves or motives of the whole bodily being.”3

Although little is known about the women disciples of Jesus, what the New Testament does record points to a profound hidden devotion and service in them, an instinctive recognition of who he was. Represented by Mary Magdalene, they were the soil in which Jesus could plant the seed of true Guru- devotion for the sake of his whole community. In John’s account his final instruction to Mary Magdalene is “Go and find my brothers and tell them.

- N. Raghunathan, trans., Sri-mad Bhagavatam (Madras and Bangalore, India: Vigneswara, 1976).

- Da Free John (Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda), Love of the Two-Armed Form (Clearlake, Calif.: The Dawn Horse Press, 1985), p. 177.

Carolyn Lee has been a student of the Way of the Heart since November 1985. She has a Ph.D. in musicology and until recently lectured in University College, Cork, Ireland, specializing in medieval music and liturgy. She writes:

I had my first encounter with Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda’s physical presence at Maria Hoop, Holland, in 1986. That unforgettable sighting of his human form showed me the truth of my heart: both the strength of my intuition of the Divine and my lifelong refusal of love.

It was a warm summer day and flies were buzzing around in the large hall where we sat. At some point a woman attendant rose from her seat and knelt by Heart-Master Da’s chair. She remained in an upright kneeling position for the entire time, brushing away any flies that came near. Her body was wholly turned to the need of Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda, and her gaze remained with him in unmoving devotion and love. I saw then what it is to be a devotee, submitted, given in body and soul to the Divine. I saw that this most graceful image of a woman at the feet of the True Heart-Master has the power to draw all men and women into the Fire of the Great One. That Fire even seemed visible to me as the two motionless forms dissolved in Radiance for a time.

Since this experience I have been inspired to search the traditions to discover the women, often hidden or in the background, who were intimate devotees of living Spiritual Masters. Coming as I do from the Christian tradition, it was natural for me to turn back to the descriptions and stories of the women who knew Jesus, to consider the gospel records about them, allowing what I had seen and felt in the company of Heart- Master Da to draw me into the Spiritual heart of these records, however meager and limited they may appear to be from an historical point of view.

Selected Bibliography

Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel of St. John and thejohannine Epistles, 3d ed. (Collegeville, Minn.The Liturgical Press, 1982)

Raymond E. Brown, The Community of the Beloved Disciple (London: Paulist Press, 1979)

Raymond E. Brown, Mary in the New Testament (Philadelphia: Paulist Press, 1978)

John Dent, The Laughing Saviour (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1976)

Keith Dowman, Sky Dancer: The Secret Life of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyal (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984) Meister Eckhart, Sermons and Treatises, vol. II, trans, and ed.

Michael Walshe (London: Watkins, 1981)

Helen Garth, Saint Mary Magdalene in Medieval Literature (Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science, Series xlvii, no. 3, Johns Hopkins University Press)

Elizabeth Moltmann, The Women Around Jesus (London; SCM Press, 1982)

Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (London: Penguin Books, 1980)

William Phipps, Was Jesus Married? (New York: Harper & Row, 1970)

Pierre, Cardinal de Berulle, Les Oeuvres, 2 vols. (Paris, 1644), Facs. Reprod. Maison d’Institution de l’Oratoire Villa Bethanie, Montsoult, “De la Magdaleine”, pp. 553ff.

Hanumanprasad Poddar, Gopi’s Love for Sri Krishna (Clearlake, Calif.: The Dawn Horse Press, 1980)

The Talks of Sadguru Upasani Baba Maharaj (Sakori, India: Upasani Sthan, 1976)

R. Wilson, The Gospel of Philip (London, 1962)

Ben Witherington III, Women in the Ministry of Jesus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984)

The Jerusalem Bible (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1966)

Srimad Bhagavatam, trans. N. Raghunathan (Madras- Bangalore: Nighneswara Publishing House, 1976)