Greetings everyone, I appreciate the opportunity to delve into the intriguing subject of Hasatan or Satan. I deliberately use this pronunciation for several reasons, including its avoidance of Anglicization and the avoidance of preconceived notions associated with the term “Satan.” Moreover, adhering to the Hebrew pronunciation aligns with the linguistic accuracy of the topic. Today, I aim to explore the figure of Hasatan and its development within the broader context of ancient Near Eastern and biblical literature.

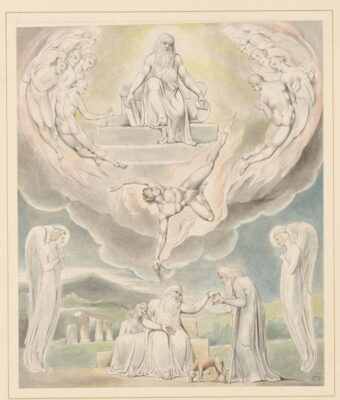

As we transition to texts explicitly mentioning Hasatan or Satan, we observe two distinct categories concerning substantival usage. Job, Zechariah (And he shewed me Joshua the high priest standing before the angel of the Lord, and Satan standing at his right hand to resist him.), Chronicles (And Satan stood up against Israel, and provoked David to number Israel.), and arguably Numbers refer to Hasatan as a celestial figure, a member of a divine council or heavenly court.

Simultaneously, the Hebrew Bible also portrays Satan as a human figure or entity, as evidenced in passages such as I Samuel 29:4. Here, the Philistines deliberate on the suitability of David for battle against the armies of Saul.

Exploring the role of Hasatan, particularly in Job, raises questions about his moral alignment. In Job, Hasatan appears to function in a positive manner, seeking to discern disinterested piety. While the presence of disinterested piety is affirmed, the complexity lies in recognizing that this is precisely the point of Hasatan’s role. As we navigate the literary history of Hasatan, we find him operating in a challenging capacity from the outset.

It appears that Hasatan is a title rather than a specific persona. Hasatan may be a member of the B’nai Elohim (Sons of God (Hebrew: בְנֵי־הָאֱלֹהִים) , and the role could be passed among different individuals over time. While the tradition eventually solidifies the notion of a single figure, it is crucial to acknowledge the uncertainty surrounding whether the writers of Job, Zechariah, and Chronicles envisioned the same figure or merely the title. I surmise Hasatan is a principle in nature and anthropomorphised to tell a story that can be understood by audiences.

In conclusion, the evolution of Hasatan’s portrayal across various texts provides a fascinating lens through which to explore the cultural and theological nuances embedded in ancient literature. As profound the subject I’ll leave it to you to ask any question without going further into the matter.

I am grateful for the opportunity to talk about this subject, and if you have any questions, please feel free to ask them. Thank you.

This talk drew heavily on Christin Rollston’s lecture which you can watch Here

***

Adversary; accuser. When used as a proper name, the Hebrew word so rendered has the article “the adversary” (Job 1:6-12; 2:1-7). In the New Testament it is used as interchangeable with Diabolos, or the devil, and is so used more than thirty times.

He is also called “the dragon,” “the old serpent” (Revelation 12:9; 20:2); “the prince of this world” (John 12:31; 14:30); “the prince of the power of the air” (Ephesians 2:2); “the god of this world” (2 Corinthians 4:4); “the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience” (Ephesians 2:2). The distinct personality of Satan and his activity among men are thus obviously recognized. He tempted our Lord in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11). He is “Beelzebub, the prince of the devils” (12:24). He is “the constant enemy of God, of Christ, of the divine kingdom, of the followers of Christ, and of all truth; full of falsehood and all malice, and exciting and seducing to evil in every possible way.” His power is very great in the world. He is a “roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour” (1 Peter 5:8). Men are said to be “taken captive by him” (2 Timothy 2:26). Christians are warned against his “devices” (2 Corinthians 2:11), and called on to “resist” him (James 4:7). Christ redeems his people from “him that had the power of death, that is, the devil” (Hebrews 2:14). Satan has the “power of death,” not as lord, but simply as executioner.

Reference: King James Dictionary