“…like Moses, we shall prove entirely faithful, most sacred theology will supervene to inspire us with redoubled ecstasy. For, raised to the most eminent height of theology, whence we shall be able to measure with the rod of indivisible eternity all things that are and that have been; and, grasping the primordial beauty of things, like the seers of Phoebus, we shall become the winged lovers of theology. And at last, smitten by the ineffable love as by a sting, and, like the Seraphim, born outside ourselves, filled with the godhead, we shall be, no longer ourselves, but the very One who made us”.

Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) by Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494)

***

THE GOSPEL AND THE GREEK MYSTERIES

By the Rev. Augustine S. Carman,

Springfield, Ohio.

1897

With an update from Brian Muraresku author of ‘The Immortality Key’, 2020

“I have fasted; I have drunk the cup”

***

he history of gospel extension in the generation following the death of Christ should include an inquiry as to the extent to which the gospel movement came into contact with the widespread observance of the ancient Mysteries. A false start made by Bishop Warburton and others in the last century, wherein absurd claims were asserted respecting a connection between the Greek Mysteries and the revelation contained in our Scriptures, doubtless had the effect of precluding serious investigation of the general subject for many years; but more recent commentators on the epistles, beginning perhaps with Bishop Lightfoot, have begun to point out some of the clearest indications of the contact between early Christianity and the Mysteries. The present writer has sought to indicate1 a particular phase of this contact as shown in the use by certain of the New Testament writers of the terminology of the Mysteries. It may be of interest to point out in a more general way the evidence of the fact that the gospel movement came into unavoidable contact with the widely prevailing observance of the Mysteries, and that certain of the New Testament writings make reference, both direct and indirect, to the fact. Each detail of orientalism, each flickering shade of local color, each ghost of a metaphor buried in the language of Scripture, is eagerly sought out in these days of critical research, and the sacred writings grow richer and more luminous with each genuine discovery.

he history of gospel extension in the generation following the death of Christ should include an inquiry as to the extent to which the gospel movement came into contact with the widespread observance of the ancient Mysteries. A false start made by Bishop Warburton and others in the last century, wherein absurd claims were asserted respecting a connection between the Greek Mysteries and the revelation contained in our Scriptures, doubtless had the effect of precluding serious investigation of the general subject for many years; but more recent commentators on the epistles, beginning perhaps with Bishop Lightfoot, have begun to point out some of the clearest indications of the contact between early Christianity and the Mysteries. The present writer has sought to indicate1 a particular phase of this contact as shown in the use by certain of the New Testament writers of the terminology of the Mysteries. It may be of interest to point out in a more general way the evidence of the fact that the gospel movement came into unavoidable contact with the widely prevailing observance of the Mysteries, and that certain of the New Testament writings make reference, both direct and indirect, to the fact. Each detail of orientalism, each flickering shade of local color, each ghost of a metaphor buried in the language of Scripture, is eagerly sought out in these days of critical research, and the sacred writings grow richer and more luminous with each genuine discovery.

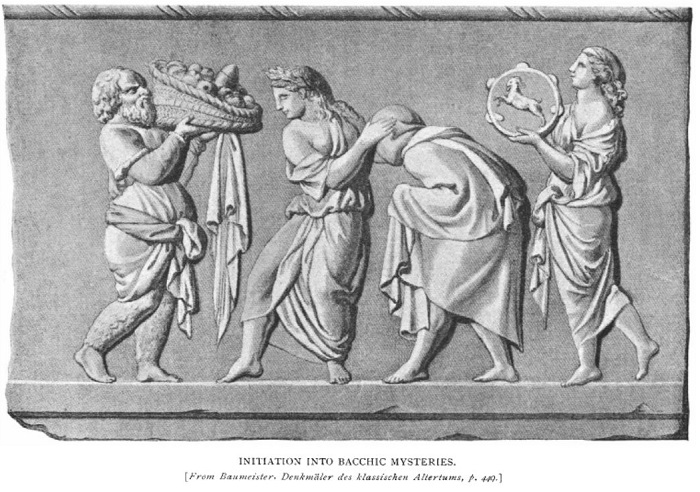

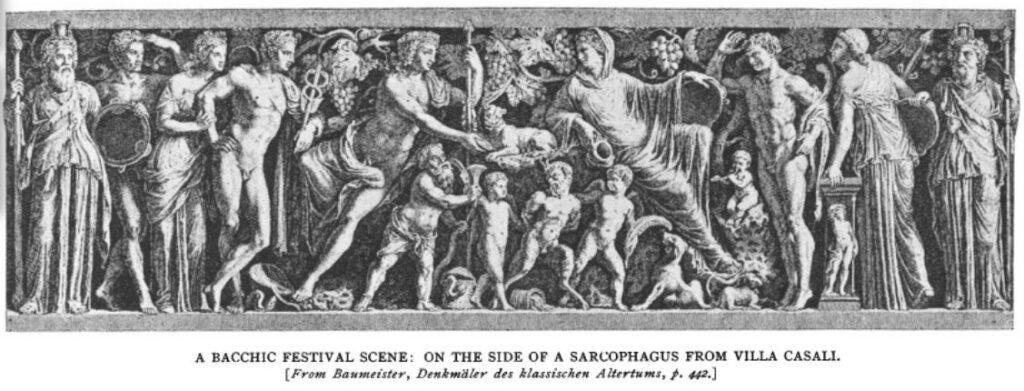

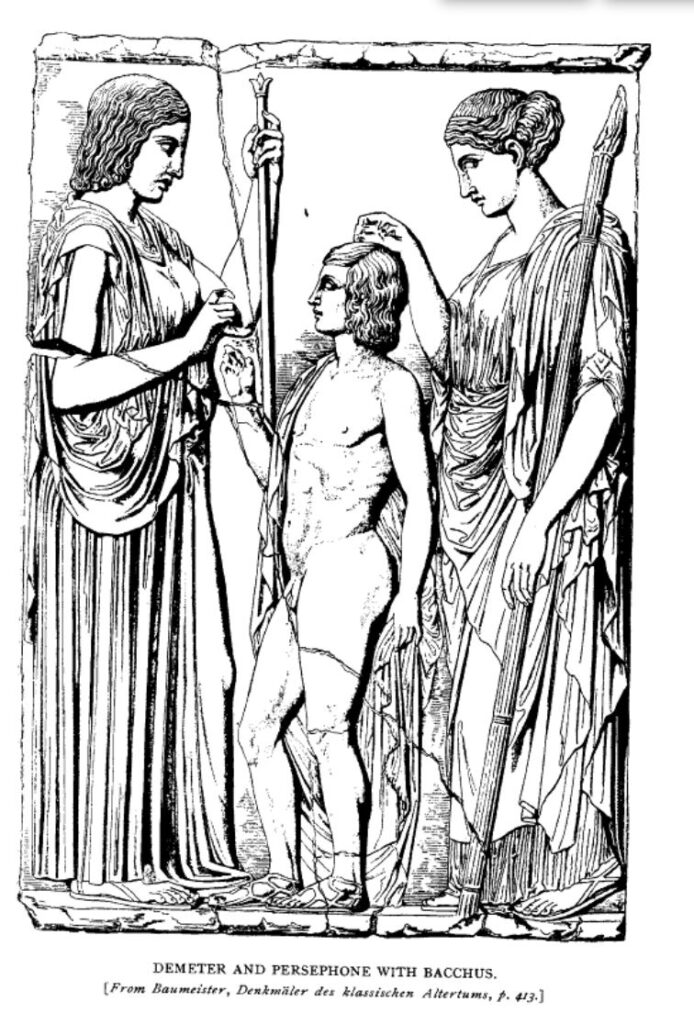

The Eleusinian Mysteries2 were the most celebrated and typical of all these Greek rites, and they came very early to embody, together with the original mysteries of Demeterand Perspehone, those of Dionysos, the Greek counterpart of Bacchus the wine god. There were the Lesser Mysteries, celebrated in the spring at Agra, a suburb of Athens; and the Greater Mysteries, celebrated at Athens and Eleusis in the fall. the later constituted a nine days’ festival, marked by public sacrifices in Athens and a Bacchic procession from Athens to Eleusis and return, the procession, especially upon he return journey, beeing charaterized at certain points by ribald jests and wild orgies.

The Eleusinian Mysteries2 were the most celebrated and typical of all these Greek rites, and they came very early to embody, together with the original mysteries of Demeterand Perspehone, those of Dionysos, the Greek counterpart of Bacchus the wine god. There were the Lesser Mysteries, celebrated in the spring at Agra, a suburb of Athens; and the Greater Mysteries, celebrated at Athens and Eleusis in the fall. the later constituted a nine days’ festival, marked by public sacrifices in Athens and a Bacchic procession from Athens to Eleusis and return, the procession, especially upon he return journey, beeing charaterized at certain points by ribald jests and wild orgies.

‘Bibliotheca Sacra, October 1893, pp. 613-39.

’ These mysteries were celebrated in Greece from about the sixth century B. C. until the downfall of the Roman Empire, and hence were flourishing throughout the entire New Testament era.’

***

Beezone addition and update.

“The Orders” – Constantine

341 a.d. – CT 16.10.2 – Constantius (Constantine)

Pagan superstition and sacrifices are completely forbidden, in accord with the law set forth by Constantine.

[The law of Constantine referred to may be from 324 just after the victory of Licinius but see the note on the authenticity of anti-pagan legislation in the Life of Constantine and Curran (listed in note), p. 185] – Mylonos – Imperial Laws and Letters Involving Religion, AD 311-364

***

Brian Muraresku author of ‘The Immortality Key’

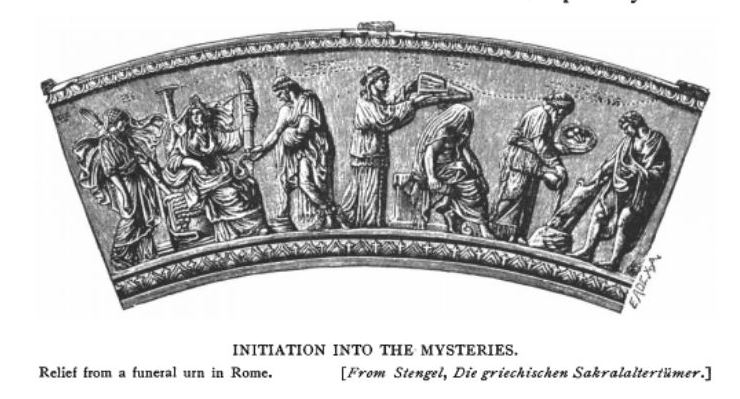

Upon the arrival at Eleusis tere followed an all-night wandering march about the region by a procession hbearing lighted tourches in imitation of the wandering search of Demeter for her lost daughter Persephone. Then came the waiting of the candidates for initiation with extinguished torches outside the (“temple”), in darkness and profound silence, until suddenly the doors of the brilliantly lighted temple were flung open, and in a blaze of dazzling light the candidates were admitted to a vision of certain impressive sights and ceremonies exhibited in the dead of night amidst the absolute silence of the spectators. At a given point in the ceremonies, which occupied probably three days and nights at Eleusis, there occurred a sort of sacramental touching, tasting, and handling of certain mystic relics; and a mystic formula or symbol was repeated by the (greek term to be added later)1 or candidates for initiation, as they approached their full initiation, this formula as given by Clement of Alexandria and Arnobius being as follows:

^ I have fasted; I have drunk the cup; I have received from the box; having done (or having tasted) I put it into the basket, and out of the basket into the chest.”

Another formula given by Clement and others is as follows : “/have eaten out of the drum; I have drunk out of the cymbal;

I have carried the kemos, I have insinuated myself under the pastos.” This second formula, although referred by some writers to the Phrygian Mysteries, is probably to be referred to the final night of the mystic ceremonies and the initiation into the second stage of the Mysteries at Eleusis.

whose names appear most frequently in the literature of the Mysteries are the hierophant and the mystagogue. These terms and many others appear in profusion thereafter, both in the form of direct allusion to the Mysteries and by way of metaphoric use of their characteristic phraseology. For example, the terms enlightenment and illumination, suggested by the striking transition from darkness to light in the course of the ceremonies, were speedily transferred to the use of philosophy and religion to express the idea of a transition from ignorance to knowledge or from sin to holiness. The metaphoric use of the word initiated to express one’s acquainting with previously unknown truth or practice has passed not only into ancient but into all modern speech. The ideas of concealment and revelation of truth, especially of its revelation to certain ones while others are kept in ignorance, mark another characteristic use of the terminology of the Mysteries ; and a frequent instance of the adoption of the mystic terminology in ancient literature is the allusion to truths of greater and less importance as belonging to the Greater or Lesser Mysteries. The idea of silence, so impressive and important in connection with the Mysteries, is another which figures largely in the philosophic and religious terminology of Neoplatonism and in the writings of the early church Fathers.

Some instances of this use of the terminology of the Mysteries may be given. For example, Plato compares the contemplation of the “ideas” to the contemplation of the solemn sights and sounds of the Mysteries; Chrysippus calls the discussion of the nature of the gods ![]()

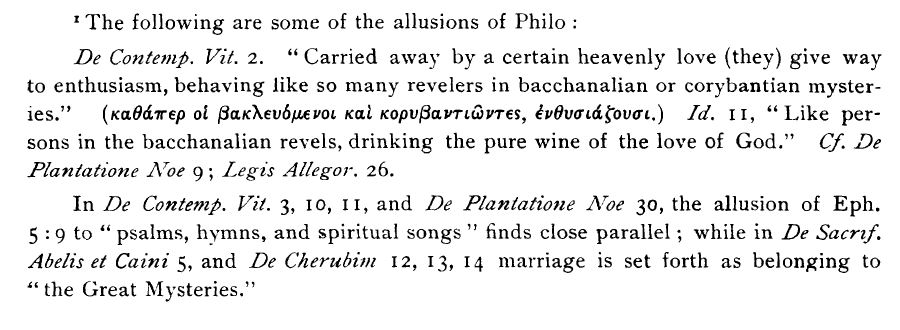

initiation ; Euripides calls sleep “the Lesser Mysteries of death/’ i. e., sleep is to death as the Lesser Mysteries are to the Greater. The writings of Philo Judaeus, who lived and wrote in Alexandria while Christ was living and probably for the greater part of a decade after the crucifixion, are of much significance for the determination of New Testament allusions to the Mysteries, for while there is no evidence in the writings of Philo of his acquaintance with the story of Christ, there is clearest evidence that the apostle Paul and other New Testament authors were familiar with the writings of Philo.1

Of the Mysteries themselves there have been the most diverse opinions. It seems likely that there were in them suggestions of lofty teaching, and of the aspiration of the soul after purification, immortality, and fellowship with the divine nature ; and that some souls were able to make use of them as an aid to their moral aspirations. On another side they were simply the rites of an agrarian festival celebrating the sowing of seed and the harvest, with the gathering of the vintage. On still another and baser side they were developed into a glorification of the reproductive powers in nature and man, which ever tended to excesses of drunkenness and lust under the sanction of religion. This will explain the terrific denunciation of the Mysteries by Clement of Alexandria and other church Fathers; and will cast sufficiently clear light upon the etymological history of the word orgies, which, from being a religious term denoting the worship of Dionysos-Bacchus, the wine god, has come to connote all that is basest in the gratification of human appetite and passion.

What contact had the Christians of the New Testament era with the Mysteries ? The answer is to be found in a study of the epistles in connection with the contemporaneous profane history and monumental records of the Mysteries.

We find for one thing sufficient evidence of the prevalence of the Mysteries in Athens, Corinth, Philippi, Rome, Ephesus, and in other cities of Asia Minor; and this evidence from outside the New Testament is complemented by allusions contained in the epistles addressed to these regions. Philippi, the scene of the apostle Paul’s first labors on the continent of Europe, is in the direct pathway of the mystic observances which are believed to have come down into Greece from Thrace. Moreover, it is known that a shrine of Dionysos was located in the mountains of Haemus near Philippi, while an elevation still nearer the city was known as the Hill of Dionysos. The suggestion has been repeated frequently by commentators that the girl of Philippi mentioned in the Acts as possessed of a spirit of divination (literally ![]() was a hierodule, or priestess, of the adjacent shrine of Dionysos. When, therefore, we find the apostle using the precise term descriptive of initiation into the first degree of the

was a hierodule, or priestess, of the adjacent shrine of Dionysos. When, therefore, we find the apostle using the precise term descriptive of initiation into the first degree of the ![]() the most reasonable explanation is that he was making allusion to observances familiar to their common life. The authorized version translates the word “I am instructed both to be full and to be hungry.” The revised version approximates the original meaning with the translation “I have learned the secret both to be filled and to be hungry.” But the literal statement is li I have been initiated into the mysteries,” i. e., of contentment both amidst plenty and in want. It seems probable also that the reference in Phil. 3: 12, 15 to perfection contains an allusion to the “perfective” rites of the Mysteries.

the most reasonable explanation is that he was making allusion to observances familiar to their common life. The authorized version translates the word “I am instructed both to be full and to be hungry.” The revised version approximates the original meaning with the translation “I have learned the secret both to be filled and to be hungry.” But the literal statement is li I have been initiated into the mysteries,” i. e., of contentment both amidst plenty and in want. It seems probable also that the reference in Phil. 3: 12, 15 to perfection contains an allusion to the “perfective” rites of the Mysteries.

The prevalence of the Greek Mysteries at Ephesus and elsewhere in Asia Minor would be expected to follow upon the Greek colonization of that region, and that such was the fact is abundantly proved. Strabo, in a well-known passage in his geography (Bk. xiv, chap. 1), has this statement: “(Pherecydes) says that the leader of the Ionian …. migration was Androclus . . . . and that he was the founder of Ephesus …. Even to the present the descendants of that race are called kings and receive certain honors as … . the superintendence of the sacrifices in honor of the Eleusinian Demeter.” Moreover, exploration at Ephesus has abundantly proved the existence of the Greek Mysteries of Demeter and of Dionysos side by side with the worship of the peculiar Ephesian divinity whom the Greeks wrongly identified with their Artemis and the Latin Diana, but who was really the counterpart of the voluptuous oriental Astarte, and among Greek divinities, of Demeter, both of them representing a deification of the reproductive powers of earth and man. Among the inscriptions from the site of the temple of Artemis (Diana) given by the distinguished explorer J. T. Wood, of the British Museum, in his Discoveries at Ephesus, the present writer has noted the following, which fully prove the presence of the Greek Mysteries at Ephesus. The following from the site of the temple is No. I1 in Wood’s list :

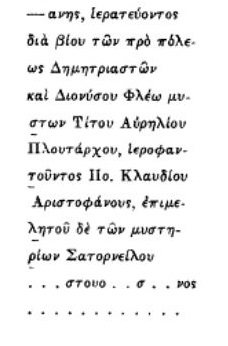

“ Resolved by the council and the people. Eupalus, son of Cronius, moved, That, whereas, Lysicon, son of Eumelus, of Thebes, proves himself loyal to the people at large, and individually to those of the citizens who have intercourse with him according as each may have invited his aid ; it is hereby resolved by the council and the people to commend Lysicon for his merit and good will, and that he be crowned with a crown of gold by the President of the games in the theater at the festival of Dionysos,” etc. This is but a specimen of many inscriptions containing explicit allusion to the Greek Mysteries, and the following important fragmentary inscription found in the suburb of Ayasalouk, near the temple, clearly indicates the joint observance of the Mysteries of Demeter and Dionysos at Ephesus, just as at Athens and Eleusis:

“ Titus Aurelius Plutarchus, being priest for life of the Demetriasts and mystai of Dionysos Phleos without the city, Publius Claudius Aristophanes being hierophant and Saturnulus being commissioner of the Mysteries….”*

*J. T. Wood, Diseaverus at Ephesus, Boston, J. R. Osgood, 1877. Inscriptions, from the City and Suburbs, No. 3. (On a loose stone found in the village of Ayasalouk, apparently part of a column.)

It will accordingly seem in no wise strange that the epistle to the Ephesians should contain instances of the use of the terminology of the Mysteries, and should make, moreover, direct allusion to the pagan rites themselves. The following are cases in point: Eph. 3:4, 5, ‘‘Whereby …. ye can perceive my understanding in the mystery of Christ; which in other generations was not made known unto the sons of men as it hath now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets in the Spirit;” 3:9, “ to make all men to see ![]() what is the dispensation of the mystery …. from all ages hid.”

what is the dispensation of the mystery …. from all ages hid.”

The ideas of concealment and revelation of truth, of enlightenment, and of the official communication or administration of these truths, are all contained here, for the words “the dispensation of the mystery” should be “the stewardship of the mystery,” precisely as in the passage quoted from Philo above, and as in 1 Cor. 4:1, “Let a man so account of us …. as stewards of the mysteries of God.”

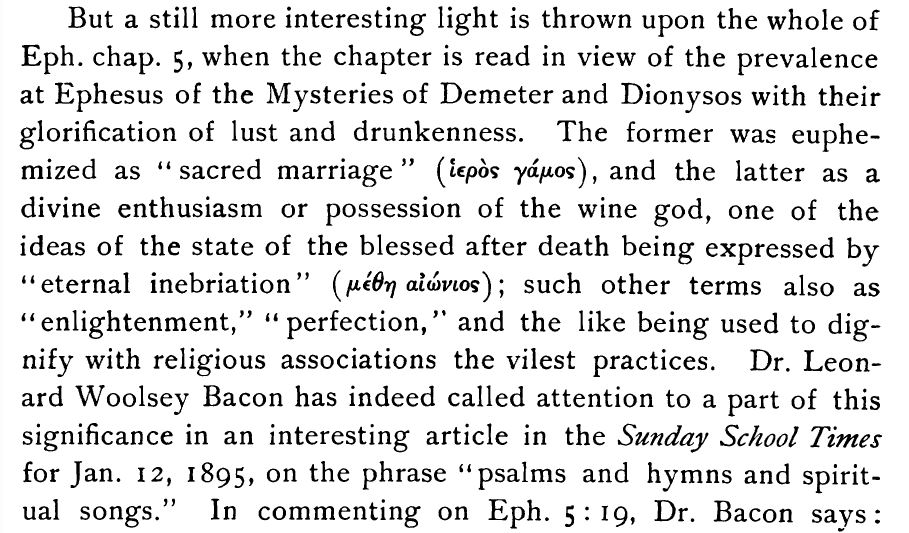

“In place of the bacchanalian orgies in which the gilded youth of Ephesus had their delight, he recommends the joyous choruses, not only of psalms and hymns, but also of those graceful and exhilarating Grecian melodies that may be joined in Christian wedlock with spiritual words and thoughts.” This interpretation seems a fair one, especially if, as seems probable, the entire fifth chapter of the epistle is replete with allusions to the alluring and debasing observance of the Mysteries so prevalent in Ephesus and other parts of Asia Minor. This conclusion is the more ineludible from the fact that the comparison of the Bacchic orgies with the worship of the true God was a familiar one at the time through the writing of Philo.1 Perhaps a free paraphrase of the chapter, designed to bring out the allusions in question, may best present the argument.

A preliminary exhortation (4: 17-32) warns Christians to walk no longer as the Gentiles walk, given themselves up to lasciviousness, to work all with covetousness; but to put away their former manner Falsehood, violent outbursts of anger, dishonesty, and vindictiveness are mentioned as besetting sins former state of paganism. They are then warned more specious temptations of vice dignfied under the gion, as indicated in the following paraphrase of Christ is your model and your sacrifice, fragrant with associations, worthy of being presented to God. But religious sanction fornication and all uncleanness and covetousness, let them not even be named among you; neither filthy and foolish jesting, although these form a part of the wonted observance of the bacchanalian festival. Let no one deceive you by the use of empty phrases such as “enlightenment,” ” perfection,” ” sacred marriage,” ” enthusiasm,” and the like, to designate these profane and debauching rites, for because of these things cometh the wrath of God upon the sons of disobedience. Be not ye therefore partakers with them, for ye were once indeed in darkness, but ye have received the true enlightenment. Walk therefore as children of the light, for the fruit of true enlightenment is in all goodness and righteousness and truth; and have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness …. for the things by them in secret in their Mysteries it is a shame even to speak of. secrecy is explained by their iniquity, for their secret rites cannot bear light. Ye have need of all care in these evil days; and it is for you to buy up the opportunity, thus redeeming the time so ruinously wasted by others, as indeed once by you also. Be wise; and seek to know the will of the Lord. In place of the drunken orgies wherein the followers of Bacchus claim to be possessed of their god, be ye filled with the Spirit; and instead of the hymns of the Bacchanalia, speak ye one to another in psalms and Christian hymns and spiritualized odes, with thanksgiving to Christ instead of praise to the god of wine and lust. Substitute for the prostitution of the marriage relation sanctioned by these Mysteries with their so-called ” sacred marriage,” and by the gross Artemis (Diana) worship of this region, the high Christian ideal of marriage, modeled as it is upon the relation of Christ to the church and expressing the highest and holiest union. And indeed this relation of the husband to the wife, and especially of Christ to his bride, may be said to belong to the true Mysteries, even to the Greater Mysteries; as is suggested by Philo Judaeus. This mys- tical doctrine of the relation of Christ to the church is of utmost importance. Howbeit see also that your own individual marriage relations be such as befit the followers of Christ.

Many other instances of the New Testament use of this ter- minology might be adduced, but these should be sufficient to indicate that the Mysteries themselves were among the promi- nent features of paganism which early Christianity met; and that the New Testament writings are to be read with this fact in mind. The instances of the use of this terminology are for the most part not direct but metaphoric allusions, the writers of the New Testament adopting terms which had entered largely into the philosophic and religious speculations of the time, and some- times perhaps with scarcely a thought of the original observ- ances. Yet the fact that this terminology occurs most frequently in the writings addressed to regions wherein from external evi- dence we know of the especial prevalence of the Mysteries indicates its use to some extent for the sake of contrasting the false and frivolous claims of the pagan Mysteries with the higher and nobler claims of the gospel. If for nothing else this study is of importance as proof of the fact that the meaning of the word mystery or mysteries in the New Testament is not at at all what