Guru’s Seclusion, Tapas, and Imprisonment

Throughout the history of the guru–disciple tradition, there are moments when the Master withdraws — into silence, seclusion, or even a form of self-imposed imprisonment. These events, often shocking or bewildering to devotees, are rarely explained in simple terms. They appear as gestures of purification, tapas (austerity), or Divine penance enacted on behalf of others. In each case, the Guru’s withdrawal reveals not escape from the world but a confrontation with the limits of human understanding and the burden of discipleship itself.

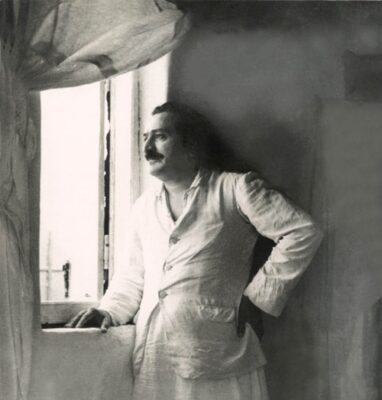

From Upasani Baba’s confinement in a bamboo cage in Maharashtra, to Meher Baba’s long periods of silence and isolation during His “Universal Work,” to Adi Da Samraj’s seclusions in Fiji and elsewhere described as “Imprisonment” or “Tapas of Seclusion,” these acts stand as living parables. They expose the tension between revelation and reception — between the Guru’s unqualified offering and the devotee’s capacity to respond.

This page gathers three such instances, not to explain them away but to recognize in them a recurring mystery: that true teaching may at times take the form of apparent withdrawal, and that the Guru’s isolation may itself be a communication — one that calls devotees to deeper responsibility, understanding, and devotion.

Upasani Maharaj, a prominent spiritual master from Maharashtra, famously confined himself in a bamboo cage for more than 14 months around 1922. This act was intended to demonstrate and teach his followers lessons in humility, selfless service, and austerity. Unlike his contemporaries such as Sai Baba of Shirdi, Meher Baba, and Mahatma Gandhi, Upasani Maharaj used severe personal discipline and unconventional methods as part of his spiritual teachings, making this episode a distinctive part of his legacy.

***

Meher Baba did His “Universal Work” at these times — work not for His own sake as He, suffering for all as God in human form, had nothing to gain — but for the spiritual advancement of all in creation.

***

Adi Da’s “Seclusion/Imprisonment/Penance”

THE BI-MONTHLY JOURNAL OF THE HEART-WORD AND BLESSING WORK OF THE DIVINE WORLD – TEACHER AND TRUE HEART-MASTER, DA KALKI:

January 3, 1990

Adi Da Samraj begins His “Tapas of Seclusion”, which He refers to as “Imprisonment”; at Indefinable, Naitauba. He has all furnishings removed and eats minimally.

11 The Kanyas take their vows as The Hridaya-Da Kanyadana Kumari Mandala Order.

February 27, 1990

At Adi Da Samrajashram, Adi Da speaks about the right relationship to Him, describing the discipline of Penance He must enact when His devotees are not responsible, to fulfill the Spiritual laws that are an inherent part of the Guru-devotee relationship.

Julie Anderson (Kanya Remembrance) edited Audio Portion

Full presentation VIDEO below

There are indeed precedents in Indian spiritual history that fit this deeper pattern — though they are rare and often misunderstood even within their own traditions. Below are several examples and parallels that align more closely with the kind of “world-work seclusion” in the above examples.

Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836–1886)

Ramakrishna occasionally entered prolonged periods of silence and physical withdrawal — not as private retreat, but to “bear the burden of humanity.” In his last years, as his body deteriorated from throat cancer, he explicitly said he was taking on the karma of his devotees, enacting a kind of mystical substitution. He told his disciples that his suffering was not his own but “for the world.”

While not seclusion in the literal sense of confinement, it was an inner withdrawal combined with outer physical restraint — a tapas performed on behalf of his circle and the larger world condition.

Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950)

During his early years at Arunachala, Ramana entered what devotees later called his “deep silence,” spending months and then years in caves such as Virupaksha and Skandashram, refusing to speak or even move. Although initially this could be interpreted as self-absorbed nirvikalpa samadhi, Ramana later explained that the withdrawal was not deliberate, but that he was “made still” so that the force of realization could stabilize the world around him. In later conversations he referred to his stillness as Isvara’s work — the divine functioning through the body. In this sense, his “seclusion” became a universal meditation, radiating peace and balance outward rather than being for personal attainment.

Anandamayi Ma (1896–1982)

Several times in her life, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, Anandamayi Ma withdrew completely from public view, even from her close disciples. She called these periods bhava-avasthā — states of divine absorption that she said were required for the world’s equilibrium. When devotees begged her to return to normal activity, she would respond that certain “forces had to be adjusted,” or that “the play of the Lord demanded seclusion.” These intervals were not penitential but cosmological — a kind of divine recalibration rather than human retreat.

Swami Ramdas (“Papa” Ramdas, 1884–1963)

Late in his life, at Anandashram in Kanhangad, Ramdas entered extended silence and minimal contact, explaining that the world’s suffering was pressing heavily upon him, and that through silence he could best transmit peace universally. His letters describe this as a “withdrawal into the inner work for the uplift of mankind.” Disciples around him interpreted it as a stage of tapas for the world, not unlike Meher Baba’s “Universal Work.”

Shirdi Sai Baba (d. 1918)

Though mostly public, there were documented intervals — notably during the late 1890s and again in 1910–11 — when Sai Baba remained withdrawn within the mosque for weeks, refusing contact and food, and was said to be “doing work for the devotees and the world.” Devotees such as Das Ganu and Mhalsapati described these as times when Sai Baba’s samadhi consciousness was addressing unseen calamities or karmic burdens affecting India.

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj (1897–1981) — brief but revealing parallel

Although Nisargadatta rarely withdrew physically, he described times when he was “drawn inward by the command of the Self” and could not teach. He explained these intervals as adjustments within the total consciousness, saying that “when the world has need of silence more than words, the Guru becomes silent.”

Modern and lesser-known parallels

-

Swami Nityananda of Ganeshpuri (c. 1897–1961) periodically sealed himself in small rooms, sometimes for weeks, telling devotees he was “doing tapas for all beings.”

-

Mother Mirra Alfassa (Aurobindo Ashram) entered deep inner withdrawal several times in the 1950s–70s, explaining that she was engaged in “combating forces that threaten the earth.” Though more aligned with the supramental yoga than bhakti traditions, her language parallels the same world-work seclusion pattern.