–

“The same ultimate truth is realized by all

free Adepts,

and they communicate it in a particular fashion in their time and

place”

Da Free John, 1982 – What

is the Conscious Process

“That is why it is said there are so many masters. They are always available.

They can always intervene. They can always be called upon.”

Why Are There So Many Masters?

The following is from:

The

Love of the God-Man

A Comprehensive Guide to the Traditional and Time-Honored

Guru-Devotee Relationship,

the Supreme Means of God-Realization,

As Fully Revealed for the First Time by Da Kalki

(The Divine World-Teacher and True Heart-Master, Da Love-Ananda

Hridayam)

By James Steinberg

SHANKARA (Sankara,

Sankaram, Sankaracarya, Sankaracharya,

SankarAcArya) (788-820) Shankara was a

great teacher of Advaita Vedanta who was likely

born in the village of Kaladi in Kerala, South

India, in 788 (although some list this date as the

beginning of his life as a renunciate). Legend has

it that he mastered the Vedas at age

eight. Shankara

critiqued the philosophical and religious

traditions of his day and singlehandedly brought

about a decisive cultural renaissance. He (and

other jnanis like him) gave overwhelming testimony

to the fact that spiritual renunciation is not

synonymous with an inactive, purely contemplative

life. Shankara wrote a

large number of Sanskrit commentaries on sacred

Hindu literature and founded five important

monasteries. ( Gorakh,

Goraksa, Goraksha, Gorakhnatha, Gorakshanatha ) (

9th or 10th century ) One of the best

known and one of the greatest masters (some say

originator) of Hatha Yoga and associated Shaivism.

May have been from the Punjab, and some suggest, he

is first to write in Hindi, or Punjabi. The Gorakh-Bodh

(“Illumination of Gorakh) is an ancient Hindi text

(12th century ?) which consists of the supposed

dialogue between Gorakhnath and his Teacher,

Matsyendra. [ The lineage

traces itself to Adinatha (Adinath, Nath, Natha)

and then Shiva himself ]. The 33 verses

deal with the such diverse topics as: the life of

the avadhuta, shunya (void), nada (sound), chakras,

japa, and sahaja. Gorakhnath is

thought to have authored the Goraksha-Samhita, the

Amaraugha-Prabodha, the Jnata-Amrita-Shastra, and

the Siddha-Siddhanta-Paddhati and

others. There is also an

old Natha sect text titled,

Gorakh-Upanishad. RAMANUJA Ramanuja ( 1017 – 1137

) Born in South

India, Ramanuja was founder of the Vishista-Advaita

(“Qualified Nondualism”) school of Vedanta and

leading theologian of the medieval bhakti

(devotion) movement. He championed Vaishnavism

(devotion to Vishnu) and was the chief opponent of

Shankara’s philosophy. Ramanuja taught

that the Absolute is not merely impersonal and

unqualified but includes in its being the

phenomenal world. He wrote brilliant commentaries

on the Bhagavad Gita, the Brahma-Sutra and the

major Upanishads. JNANESHVAR Jnaneshvar was a

great Siddha, mystic and poetic genius of

Maharashtra, India who died at the age of 21 in

enstasy. His spiritual roots were in both the nath

and bhakti traditions and listed his lineage as

Shiva, Shakti, Matsyendra, Gorakhnath, Gahini and

Nivritti (his elder brother). At the age of fifteen

(1290) he is said to have delivered ex tempore the

nine-thousand verses of his poetic commentary on

the Bhagavad Gita; Jnaneshvari (Jnaneshwari) or

“Goddess of Wisdom” [ also called

Bhava-Artha-Dipika (“Light on the meaning of

Being”)]. Jnaneshvar’s

teaching was non-dualist, saying that the mainifest

world is a “sport” (vilasa) of the Absolute; the

Love of the singular Reality, and regarded bhakti

(devotion), the means to liberation. KABIR ( 1440 – 1518

) The son of a

Moslem weaver, Kabir was born in Benares, India. A

married householder, he earned his livelihood from

weaving and became one of the most influential

figures of northern India and has been hailed as

the “Father of Hindi literature”. His spiritual

growth was equally guided by the Sufi poetry of the

great Persian mystics (Rumi among them) and by the

Hindu teacher Ramananda. While Kabir converted to

Hinduism, all his life Kabir sought to unite the

conflicting streams of Muslim and Hindu

spirituality. He attracted both Muslim and Hindu

disciples and referred to God as both Allah and

Rama. He spoke the

language of the ordinary people, infusing it with

the brightness of his Realization. In many popular

verses, Kabir extols the supreme help afforded by a

true Master and praises the devotion in the

disciple. He sings of the “dice of love” which are

to be cast on the body as the board, according to

the throw learned from the Heart-Master. His following

today, called the Kabirpanthir, still numbers

nearly one million adherents. He was also a

forerunner of Sikhism, which was founded by Guru

Nanak, his disciple. CHAITANYA ( 1486 – 1553

) Chaitanya was a

legendary bhakta and master of God-intoxication,

whose life story reads like the play and sport of

Krishna (and some believe him to be the

re-incarnation). For the last twelve years of his

life, he is said to have lived in perpetual

devotional ecstasy or “Divine Madness”

(“divyaunmada”). A tall, muscular

man, he considered himself the bride of Krishna.

Chaitanya demonstrated in his own life how the dry

ritualism of his brahmanical peers could be turned

into true worship. Lost in God, he would dance,

often in public, and with his entranced dance

attract others into God-Communion. TUKARAM ( Tukarama,

Tukaram Maharaj, Tuka ) ( 1608 – 1649 ) (

1598 – 1650 ) Tukaram was a

bhakta by nature and farmer by trade and was likely

born at Dehu near Poona in the State of Maharashtra

where his ancestral home is still said to

exist. His family were

successful grain sellers but the priestly class

considered him lowborn. (Tukuram’s own

farming fortune took a bad turn later in life when

a famine resulted in the death of his first wife

and son by starvation.) Tukuram inherited

devotion to God from his family. The family deity

was Vitthal, or Pandurang— a form of Krishna

worshipped in the famous temple in Pandharpur. His

devotion took greater focus after the disaster that

befell his family and many others. Some say Tukaram

received his spiritual initiation from Chaitanya in

a dream. Others say that it was during a period of

intensive meditation that Tukaram’s Guru, Babaji

Raghavachaitanya, initiated him in 1619, whereupon

he renounced his inheritance gave himself

completely to meditation and

kirtan. Tukaram believed

the body to be the temple of the living lord and

idol worship and rituals had no meaning for him.

His all-embracing love and forbearance and his

special compassion for animals compare with the

saintliness of St. Francis of

Assisi. He had much need

to be forbearing, for his envious comtemporaries

from the upper classes condemned and reviled him

for his spontaneous witnessing of the Love of God.

Oblivious to the misunderstanding and spite of his

detractors, Tukaram bequeathed to his fellow men

and posterity many wonderful songs, chants and

poems in praise of the Divine and the spiritual

Way. Nearly five thousand lyrics in the Marathi

language have been consolidated into a volume known

as the Tukaramachi Gatha. RAMPRASAD

( 1718 – 1778

) Ramprasad Sen was

a Bengali Hindu poet-saint who worshipped the

Divine in its female aspect, as Kali or the Mother

Goddess. He was an exemplar of “bhakti yoga”,

charactersized by practice of direct and intensely

personal forms of relationship with the Divine

Reality. Ramprasad’s

poetry expresses a passionate mysticism, filled

with intense longing and struggle. He addresses the

Mother Goddess in all of Her seemingly

contradictory aspects—as loving mother and

“the Dark One’, as the Transcendental Reality and a

disreputable trickster embodying the forces of

“maya” or illusion. While Ramprasad’s

relationship to the Divine Mother seems at times

petulant, irreverent, even blasphemous, such forms

of address and acknowledgment are occasionally

employed in Indian devotional verse, and do not

contradict his bhakti orientation. Ramprasad

translators Leonard Nathan and Clinton Seely

write: [This]

convention is a means of revealing the power in

that relation, once established, to transform every

kind of emotion—hostile as well as

loving— into devotional passion through the

act of total concentration on the deity. [It

also exhibits] what is essential in the

relations between devotee and

deity. For when

Ramprasad accuses Kali of indifference, he is also

suggesting her total detachment from the world, the

very quality that he needs to achieve for release,

just as when he acesses her of shameless nakedness,

intoxication, and madness, he is, in fact,

cataloguing some of her most potent attributes: the

awesome presence of real being, without the

conventional covering of appearance; the joy of

true freedom, and its refusal to be contained in

rational or moral categories…. The convention of

accusation and insult, in short, provides Ramprasad

with an intensity and depth of feeling to match the

awesome crisis of salvation. AKKALKOT MAHARAJ (Shri Swami

Samarth) (19th

century) Akkalkot Maharaj,

recognized by many as an incarnation of Dattatreya,

first appeared in Akkalkot in 1856. There he stayed

for nearly twenty-two years. When asked about his

parentage and childhood, he gave various, sometimes

contradictory, answers to

inquirers. One account put

forth by deotees asserts that after traveling in

the Himalayas, the Swami sat in samadhi for three

hundred years in a dense forest. He became

completely covered by anthills, and a large tree

grew beside him. Once a woodcutter came to the

forest and chose that particular tree for cutting.

Laying his axe first to the anthill, he was

surprised to see blood oozing from it. Pulling down

the anthill, he discovered the Swami beneath

it. Roused from

samadhi, the Swami declared the incident to be

Divinely ordained as it was time for him to go into

the world and continue his mission. The Swami is

said to have then wandered for a hundred years,

performing many miracles, before appearing in

Akkalkot. The Swami was

unpredictable, appearing mad to many, and full of

miracles. He loved his devotees with a great

passion, and like other Adepts of the Crazy Wise

style, he was paradoxically full of both human and

Divine qualities. Once, when asked who he was, he

replied, “I am this infinite universe; I am

everywhere. Yet my favorite resorts are Sakyodri,

Girnar, Kasi, Mathapur, Karveer, Panchaleswar,

Audumbar, Karanjnagar, Narasimhvadi, and Gangapur.”

MAHARISHI BRAHMANANDA

BRAHMACHARI ( ? – 1906

) Not known in the

West and barely known in the East, Brahmananda, of

Gangonath, Baroda, India is known to have activated

the spiritual process in others by his mere glance.

A man of miracles, Brahmananda lived in extreme

austerity in a remote cave, though during a severe

famine he was found dispensing food to thousands of

victims from a seemingly inexhaustible

supply. TRAILANGA SWAMI There are four

short references to Trailanga Swami in The Gospel

of Ramakrishna. The longest, in Swami

Nikhilananda’s introduction, describes

Ramakrishna’s vision of Siva in Benares; “with

ash-covered body and tawny matted hair, serenely

approaching each funeral pyre and breathing into

the ears of the corpses the mantra of

liberation.” He paid a visit

to Trailanga Swami, “the celebrated monk, whom he

later declared to be a real paramahamsa, a

veritable image of Siva.” Ramakrishna also

describes the Swami as having taken a vow of

silence “when he is truly aware of Unity,” but also

quotes him regarding the mind, so apparently he was

not always silent (or wrote). In Autobiography

of a Yogi, Paramahansa Yogananda, describes

Trailanga Swami on pages 291-295; TOTAPURI (Tota

Puri) According to

Swami Nikhilananda, in his introduction to the The

Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Totapuri was likely born

in the Punjab. He was trained at an early age in

Advaita Vedanta and looked upon the world as an

illusion. He regarded the

gods and goddesses (and all its rituals) of

dualistic worship as mere fantasies of the mind. He

spent forty years practicing austere disciplines of

self-exertion and will-power on the banks of the

sacred Narmada and “liberated himself” from the

sense objects of the universe and realized his

Identity with the Absolute. By the time he

arrived at Dakshineswar Temple (after a visit to

the estuary of the Ganges) in 1864, he was a

wandering monk of the Shankara Order and the head

of a monastery in the Punjab and claimed leadership

of seven hundred sannyasins. Totapuri

recognized in Sri Ramakrishna an advanced seeker of

Truth and thought he would be a fit recipient of

the Vedantic ideal. He therefore asked Sri

Ramakrishna whether he would like to practice

Vedanta. Sri Ramakrishna replied that he would do

so, if his ‘Mother’ permitted him. Totapuri asked

him to get his mother’s permission quickly, as he

would not stay at Dakshineswar for long. Sri

Ramakrishna went to the Kali temple and heard Her

command: ‘Yes, my boy, go and learn of him. It is

for this purpose he has come here. He was “a teacher

of masculine strength, a sterner mien, a gnarled

physique, and a virile voice”. Ramakrishna would

soon affectionately address the monk as Nangta, the

“Naked One”, because his total renunciation of the

world included clothing. Ramakrishna

referred to Totapuri as a Jnani and liked to tell

the story of Totapuri giving him the Gift of the

Absolute while he, Ramakrishna, gave Totapuri the

Gift of Worship of the Goddess. RAMAKRISHNA ( born Gadadhar

Chattopadhyay ) ( 1836 – 1886 )

VIVEKANANDA Swami

Vivekananda ( 1863 – 1902

) SHIRDI SAI BABA Sai Baba of

Shirdi ( 1831( ?) – 1918

) UPASANI BABA (this

page is under construction) NARAYAN MAHARAJ Narayan

Maharaj ( 1885 – 1945

) RAMANA MAHARSHI Ramana

Maharshi ( 1879 – 1950

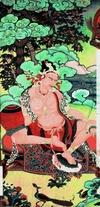

) PADMASAMBHAVA (Padmasambhava,

Sambhava, Padmakara, Pema Jungney, Guru Rinpoche,

Precious Guru, Master Padma, Precious Master, Guru

Tsokyi Dorje, Loden Chogsey, Shakya Senge, lit.

“Lotus-Born”) ( 8th century ) ( 717 ? – 762

) When Lord Buddha

was about to pass into final Nirvana, he said to

his followers, “This worldly life is transitory and

separation is inevitable. But eight years from now,

in the midst of an immaculately pure lake in the

northwest

land of

Uddiyana, one will appear who is wiser and more

powerful than myself. Born from the center of a

lotus blossom, he will be known as Padmasambhava

and will reveal the teachings of the Secret Mantras

to deliver all beings from misery.” ( Tilo, Tillo,

Tillipa, Tailopa, Telopa, sNum-pa, Mar-nag

‘tsong-mkhan, Til-brdung-mkhan )

(9881069) The Song of

Mahamudra (excerpt) by Tilopa Mahamudra is

beyond all words ( 1016

1100 ) Although born in

the Fire-Male-Dragon year of 1016 in Bengal, India,

Naropa occupies a “unique position” in the history

of Tibetan Buddhism. “To the present day his life

is held up as an example to anyone who aspires

after spiritual values, which are never realized

the easy way but only after years of endless toil

and perseverance. It took Naropa twelve years of

ardent devotion and indefatigable service to his

Guru Tilopa to attain his goal: the overwhelming

experience of the Real in direct knowledge. Apart

from this, Naropa also marks the beginning of a new

and rich era of Buddhist thought in Tibet, while at

the same time he is the culmination of a long

tradition. None of his contemporaries or successors

in India can compare with him in depth of

experience When he had

reached the age of eleven he went for study to

Kashmir, at that time the main seat of Buddhist

learning. He stayed there for three years and

having acquired a solid knowledge of the essential

branches of learning he returned home in A.D. 1029.

A large number of scholars went with him and for a

further three years he continued his studies in

their company. But then in A.D. 1032 he was forced

to marry. His wife came from a cultured Brahmin

family. The marriage lasted for eight years, then

it was dissolved by mutual consent . .

. In A.D. 1049

Naropa went to Nalanda where he took part in a

religious-philosophical debate. He was successful

in this and was elected abbot, a post he held for

eight years. The year A.D. 1057 was decisive for

his spiritual development. He resigned from his

post and set out in search of Tilopa who had been

revealed as his Guru in a vision. After an ardent

search which almost ended in suicide he met Tilopa

and served him for twelve years until the latter’s

death in A.D. 1069. Naropa himself died in the

Iron-Male-Dragon year (A.D. 1100). His mortal

remains were preserved in the Kanika (Kaniska)

monastery at Zangskar.” MARPA (the

Translator) (Marpa Lotsawa,

Marpa Chökyi Lodrö) ( 1012 – 1097 ) (

1012 – 1099 ) MILAREPA Milarepa (Mi-La-Ras-Pa,

Jetsün Milarepa,

Jetsèun-Milarepa) ( 1040 – 1123 ) (

1040 – 1143 ) ( 1052 – 1135 ) DRUKPA KUNLEY BODHIDHARMA ( Dharma, Tamo in

Chinese, Daruma in Japanese ) (470-543)

(?-528) The First

Patriarch (Chinese Line) Bodhidharma was

the 28th Patriarch in the Indian lineage (after

Buddha) and probably not acknowedged to be the

First Patriarch in the Chinese line until the time

of the Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) According to D.

T. Suzuki 1 , Dharma was the third son of the King

of Hsiang-chih (Kasi?) in southern India. He became

a monk and studied under Prajnatara (the 27th

Indian Patriarch) for some forty years, it is

said. “After the death

of his teacher, he assumed the patriarchal

authority of the Dhyana school, and energetically

fought for sixty years or more against heterodox

schools. After this, in obedience to the

instruction which he had received from Prajnatara,

he sailed for China, spending three years on the

way. In the year 520

he at last landed at Kuang-chou in Southern China

… [Finding ill-treatment at the hands of both

commoners and elite, Dharma] went to the State

of Northern Wei, where he retired into the Shao-lin

monastery. It is said that he spent all his time,

during a period of nine years there, silently

sitting against the wall and deeply absorbed in

meditation, and for this singular habit he is said

to have earned the title of “the wall-gazing

brahmin”. HAN SHAN – SHIH

TE “Han-shan and

Shih-te (Kanzan and Fittoku)” from a Japanese

hanging scroll by Hashimoto Gaho. Han-shan (“Cold

Mountain”), and his sidekicks Shih-te (“Pick Up” or

“Foundling”), and Fengkan (“Big Stick” as he was

six-foot tall), were known as the “Tian-tai Trio,”

wandering Tang Dyansty lunatic hermit-monks, who

sometimes lived at the Guoqing Temple of the

Tian-tai sect in the Tian-tai mountain range by the

East China Sea. They, like Monk Ji-gong, were known

for their unconventional behavior as well as their

poetry. “Han Shan and

Shih-te are two inseparable characters in the

history of Zen Buddhism, forming one of the most

favourite subjects of Sumiye painting by Zen

artists. Han Shan was a poet-recluse of the T’ang

dynasty. His features looked worn out, and his body

was covered in clothes all in tatters. He wore a

head gear made of birch-bark and his feet carried a

pair of sabots too large for them. He frequently

visited the Kuo-ch’ing monastery at T’ien-tai,

where he was fed with whatever remnants there were

from the monk’s table. He would walk quietly up and

down through the corridors, occasionally

talkingaloud to himself or to the air. When he was

driven out, he would clap his hands and laughing

loudly would leave the monastery.” HUI NENG ( Hui-Neng,

Hui-neng, Dajian Huineng, Hui-Neng Liu-Tsu-ta, Wei

Lang ) ( Yeno, Eno

[in Japanese] ) ( The Sixth

Patriarch, The Sixth Ancestor )( Chinese Line

) ( 638 – 713

) According to D.T.

Suzuki 2 “The Sixth Patriarch, Hui-neng, was a

great religious genius, and his life marks an epoch

in the history of the Zen Sect in the Far East. It

was due to him that his Sect, hitherto

comparatively inactive and rather tending to

ascetic quietism, now assumed a more energetic role

in the demonstration of its peculiar features, and

began to make its influence more and more felt,

especially among the thoughtful class of people.,”

(not to mention Enlightenment to the prepared

few). According to

Fa-hai 3 , (early biographer and contributor to the

Hui Neng legend) in his introduction to the

Platform Sutra: ” When he was born beams of light

rose into the air and the room was filled with a

strange fragrance. At dawn two mysterious monks

visited the Master’s father and said: “The child

born last night requires an auspicious name; the

first character should be ‘Hui,’ and the second,

‘Neng'”. “What do ‘Hui’

and ‘Neng’ mean?” inquired the father. The priest

answered: “‘Hui’ means to bestow beneficence on

sentient beings; ‘Neng’ means the capacity to carry

out the affairs of the Buddha.” When they had

finished speaking they left, and there is no one

who knows where they went.” HUAI JANG (Huai-Jang Nan-Yueh, Hoai

Nhuong) The famous

tile-grinding story refers to Great Master Ma Tsu

Tao-I’s meeting with his teacher, Huai Jang of Nan

Yueh, one of the foremost heirs of the Sixth

Patriarch Hui Neng. Here is the excerpt from the

Ching Te Ch’uan Teng Lu (Record of Transmission of

the Lamp) as rendered by Cleary and Cleary in the

appendix to The Blue Cliff Record: During the K’ai

Yuan era (713 – 741) an ascetic named Tao-I was

dwelling in the Ch’uan Fa Temple; all day he sat

meditating. Huai Jang knew that he was a vessel of

Dharma, and went to question him: “Great Worthy,

what are you aiming at by sitting

meditation?” Ma replied, “I

aim to become a Buddha.” Jang then took a

tile and began to rub it on a rock in front of the

hermitage; Ma asked him what he was doing rubbing

the tile. Jang said, “I am

polishing it to make a mirror.” Ma said, “How can

you make a mirror by polishing a tile?” Jang said,

Granted that rubbing a tile will not make a mirror,

how can sitting meditation make a

Buddha?” Ma asked, “Then

what would be right?” Jang said, “It is

like the case of an ox pulling a cart: if the cart

does not go, would it be right to hit the cart or

would it be right to hit the ox?” Ma didn’t

reply. Jang went on to

say, “Do you think you are practicing sitting

meditation, or do you think you are practicing

sitting Buddahood? If you are practicing sitting

meditation, meditation is not sitting or lying. If

you are practicing sitting Buddahood, ‘Buddha’ is

not a fixed form. In the midst of transitory

things, one should neither grasp nor reject. If you

keep the Buddha seated, this is murdering the

Buddha; if you cling to the form of sitting, this

is not attaining its inner principle.” Ma heard this

teaching as if he was drinking ambrosia. He bowed

and asked, “How shall I concentrate so as to merge

with formless absorption?” Jang said, “Your

study of the teaching of the mind ground is like

planting seeds; my expounding the essence of

reality may be likened to the moisture from the

sky. Circumstances are meet for you, so you shall

see the Way.” Ma also asked,

“If the Way is not color or form, how can I see

it?” Jang said, “The

reality eye of the mind ground can see the way.

Formless absorption is also like this.” Ma asked, “Is

there becoming and decay, or not?” Jang said, “If

one sees the Way as becoming and decaying,

compounding and scattering, that is not really

seeing the Way. Listen to my verse: Mind ground

contains various seeds; When there is moisture, all

of them sprout. The flower of absorption has no

form; What decays and what becomes?” Ma heard this and

his understanding opened up. His heart and mind

were transcendent. He served his master for ten

years, day by day going deeper into the inner

sanctum. (This meeting

probably took place in the mid 730’s. Huai Jang had

six adept pupils, but he said it was Ma Tsu who

realized his “heart.”) SHIH T’OU (Shitou Xiqian,

Shih-t’ou Hsi-ch’ien, Shitou Heshang) (Kao Yao, Gao

Yao, Sekito Kisen) ( 700 – 790

) Song of the Grass

Shack I’ve built a

grass shack with nothing of value inside. After a

good meal, I like to take a nice nap. The grass

thatching still looks new; When it wears out, I’ll

add fresh thatch to the roof. The person inside the

shack is always present, But you won’t find him

inside or out. He doesn’t hang out with worldly

people, And he doesn’t like the things they like.

This little shack contains the entire universe, And

my physical body is integrated with it. Great

Bodhisattvas don’t doubt my ideas, Although humans

may think them strange. If you say that my hut

looks shabby, I’ll answer. That the One Mind

abides right where it is. East or west, north or

south, A solid foundation is what counts. With

green pines hanging over the roof And bright

windows in the walls, not even a royal palace can

compare with my shack. With a monk’s robe over my

shoulders And a hood over my head, I’ve got no

worries at all. It’s not that I praise myself for

living here, Like some merchant pushing his

product. It’s just that when the twilight comes, My

mind is limitless from front to back. MA TSU (Ma Zu, Mazu

Daoyi, “Daji”, Ma To, Ma To Dao Nhat) ( 708 – 807 ) (

709 – 788 ) HUI

HAI PAI

CHANG HUANG

PO LIN

CHI HAN

SHAN HSU

YUN DOGEN IKKYU HAKUIN (this

page is under construction) (this

page is under construction) (this

page is under construction) (this

page is under construction)

And symbols, but for you, Naropa,

Earnest and loyal, must this be said.

The Void needs no reliance,

Mahamudra rests on nought.

Without making an effort,

But remaining loose and natural,

One can break the yoke

Thus gaining Liberation.

If one sees nought when staring into space,

If with the mind one then observes the mind,

One destroys distinctions

And reaches Buddhahood.

D. T. Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, Third Series,

1953, p. 160