To-Morrow of Death

OR

Our Future Life According to Science

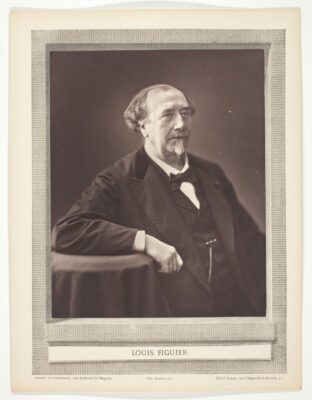

by Louis Figuier

1872

INTRODUCTION.

Reprinted in 1904

READER, you must die. You may perhaps die to-morrow. What will become of you? What shall you be, on the day after your death? I do not now allude to your body; that is of no more importance than the clothes which it wears, or the shroud in which it will be buried. Like these garments, like that cerecloth, your body must be decomposed, and its elements distributed among Nature’s great reservoirs of material, earth, air, and water. But your soul, whither shall it go? That which was free within you, that which thought, loved, and suffered, what shall become of it? Of course you do not believe that your soul will be extinguished with your life on the day of your decease, and that nothing will remain of that which has palpitated in your breast, vibrating to the emotions of joy and sorrow, to the tender affections, the numberless passions and disturbances of your life.

Where shall that sensible, existing soul, which must survive the tomb, go to? What will it become, what shall you be, my reader, the day after your death?

To the consideration of this question this book is devoted.

Almost all thinkers have declared that the problem of the future life defies solution. They have argued that the human mind is powerless to foresee so profound a mystery, and that therefore the only rational course is to abstain from the endeavour. This is the reasoning of the majority of mankind, partly from carelessness, or partly from conviction. Besides, when we venture to look at this tremendous question closely, we find ourselves immediately surrounded with such thick darkness that we lack courage to pursue the investigation. And thus we are led to turn away from all thought of the future life.

There are, nevertheless, circumstances which force us to reflect on this dark and difficult subject. When one finds oneself in danger of death, or when one has lost a dearly beloved object, there is no escape from meditation upon the future life. When we have dwelt long and earnestly upon the idea, we may be brought to acknowledge that the problem is not, as it has so long been believed, beyond the reach of the human mind.

During the greater portion of his life, the author of this book believed, in common with everybody else, that the problem of the future life is out of our reach, and that true wisdom consists in not troubling our minds about it. But, one dreadful day, a thunderbolt fell in his path. He lost the son in whom centred all the hope and ambition of his life. Then, in the bitterness of his grief he reflected deeply on the new life which must open for each of us, above the tomb. After long dwelling on this idea in solitary meditation, he asked of the exact sciences what positive information, on this question, they could furnish him with, and subsequently, he interrogated ignorant and simple people, peasants in their villages, and unlettered men in towns, an ever precious source of aid in re-ascending towards the true principles of nature, for it is not perverted by the progress of education, or by the routine of a commonplace philosophy.

Thus the author of this book succeeded in constructing for himself an entire system of ideas concerning the new life of man, which is to follow his terrestrial existence.

But his system is all contained in nature. Each organized being is attached to another which precedes, and another which follows it, in the chain of the living creation. The plant and the animal, the animal and the man, are linked, soldered to one another; the moral and physical order meet and mingle. It results from this, that any one who believes himself to have discovered the explanation of any one fact concerning this organization, is speedily led to extend this explanation to all living beings, to reconstruct, link by link, the great chain of nature. Thus it was with the author of this book. After having sought out the destination of man, when dismissed from his terrestrial life, he was led to apply his views to all other living beings, to animals, and then to plants. The power of logic forced him to study those beings, impossible to be seen by our organs of vision, by which he holds the planets, the suns, and all the innumerable stars dispersed over the vast extent of the heavens, to be inhabited. So that you will find in this book, not only an attempt at the solution of the problem of the future life by science, but also the statement of a complete theory of nature, of a true philosophy of the universe.

It may be that I am deceiving myself; it may be that I am taking the dreams of my imagination for serious views; I may lose myself in that dark region through which I am trying to grope my way; but at least I write with absolute sincerity, and that is my excuse for writing this book at all. I hope that others may be induced by my example to attempt similar efforts, to apply the exact sciences to the study of the great question of the destinies of man after this life. A series of works undertaken in this branch of learning, would be the greatest service which could be rendered to natural philosophy, and also to the progress of humanity.

After the terrible misfortunes of 1870 and 1871, there is not a family in France which has not had to mourn a kinsman or a friend. I found, not indeed consolation for my grief, but tranquillity for my mind, in the composition of this work; and I have therefore hoped that, in reading its pages, they who suffer and they who grieve might find some of the same hope and assurance which have lifted up my stricken heart.

Society is in our day the prey of a deadly disease, of a moral canker, which threatens it with destruction. This disease is materialism. Materialism, which was preached first in Germany, in the universities, and in books of philosophy, and the natural sciences, afterwards spread rapidly in France. With brief delay, it came down from the level of the _savans_ to that of the educated classes, and thence it penetrated the ranks of the people; and the people have undertaken to teach us the practical consequences of materialism. Little by little they have flung off every bond, they have discarded all respect of persons and principles; they no longer value religion or its ministers; the social hierarchy, their country, or liberty. That this must lead to some terrible result it was easy to foresee. After a long period of political anarchy, a body of furious madmen carried death, terror, and fire through the capital of France.

It was not patriotism which fired the illustrious and sacred monuments of Paris, it was materialism. Nothing can be more evident than that, from the moment one is convinced that everything comes to an end in this world, that there is nothing to follow this life, we have nothing better to do, one and all of us, than to appeal to violence, to excite disturbance, and invoke anarchy everywhere, in order to find, amid such propitious disorder, the means of satisfying our brutal desires, our unruly ambition, and our sensual passions. Civilization, society, and morals, are like a string of beads, whose fastening is the belief in the immortality of the soul. Break the fastening, and the beads are scattered.

Materialism is the scourge of our day, the origin of all the evils of European society. Now, materialism is fiercely fought in this book, which might be entitled, “Spiritualism Demonstrated by Science.” Because this is its aim, and its motive, my friends have induced me to publish it.

Read more: