Harvard’s Henry Beecher LSD Research – 1950’s

Earlier LSD Work

Harvard (1956)

“While Leary stands out as an early pioneer of psychedelic research at Harvard, it is rarely appreciated that Dr. Henry Knowles Beecher had published important work on the psychology of LSD some 4 years earlier.”

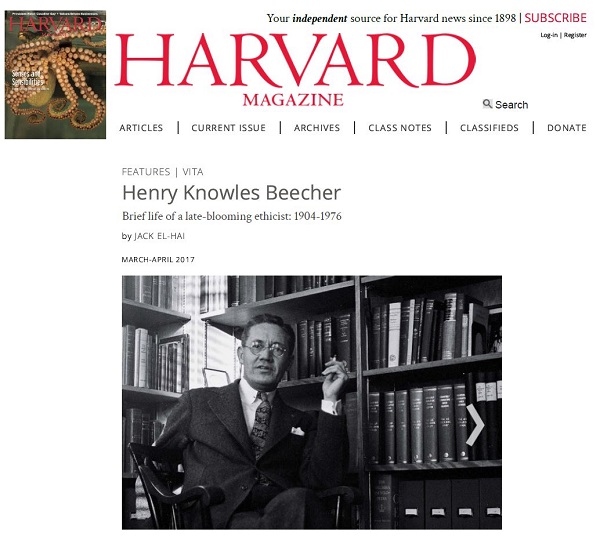

Lyscrgic acid diethylamide (LSD) was brought to national attention by Dr. Timothy Leary. Leary was a well-respected psychologist on the faculty of Harvard University who developed an interest in hallucinogens after a personal experience with psilocybin in 1960 and ultimately developed this interest into both a scientific study and a cultural vision. Throughout the early 1960s, Leary and his colleagues – Dr. Ralph Metzner and Dr. Richard Alpert explored the effects of psychedelics at Harvard, resulting in both fame and infamy – especially for their studies on students. While Leary stands out as an early pioneer of psychedelic research at Harvard, it is rarely appreciated that Dr. Henry Knowles Beecher had published important work on the psychology of LSD some 10 years earlier. How is it that Beecher found his way to the study of LSD? The answer to this question is a fascinating history that spans from the shores of Italy in the 1940s to the frontiers of bioethics in the 1960s. It appears heretofore unrecognized that Beecher’s study of LSD in the 1950s may bear an important relationship to virtually all of his other endeavors.

George A. Mashour, MD, PhD University of Michigan Medical SchoolArm Arbor. Michigan

Study was done in 1956

“United States intelligence agencies working through the US government financed drug research. An example is that Dr. Beecher of Harvard University was given via the US Army Surgeon General’s Office $150,000 to investigate “the development and application of drugs which will aid in the establishment of psychological control.” – George A. Mashour.

While Leary stands out as an early pioneer of psychedelic research at Harvard, it is rarely appreciated that Dr. Henry Knowles Beecher had published important work on the psychology of LSD some 10 years earlier.

How is it that Beecher found his way to the study of LSD? The answer to this question is a fascinating history that spans from the shores of Italy in the 1940s to the frontiers of bioethics in the 1960s. It appears heretofore unrecognized that Beecher’s study of LSD in the 1950s may bear an important relationship to virtually all of his other endeavors.

Beecher’s Research on LSD

In 1956, Beecher and coinvestigators published a study on LSD and a related compound lysergic acid monoethylamide. It is important to note that LSD was legal at this time and remained so until the mid-1960s. The subjects in the study were given predrug and postdrug Rorschach tests and psychologic evaluations and vital signs were observed. It was found that the degree of change in the subject’s interpretation of the Rorschach tests was positively correlated with preexisting “personality disturbances or maladjustment.”

While certainly an interesting scientific investigation, a question naturally arises: why would Henry K. Beecher, whose early work was on the more orthodox topics of pain and pulmonary physiology’, be studying Rorschachs and hallucinogens in his “Anesthesia Laboratory”? One answer is that the study reflects Beecher’s interest in the preexisting mood and the subjective response of individuals receiving drugs. Indeed, Beecher and his coinvestigators—Dr. Louis Lasagna and Dr. John von Felsinger—published a broader 2-part investigation on mood and drugs in the 1950s.

LSD, as was noted in the discussion of one of his papers, was one of the most potent agents in inducing changes on the Rorschach test and could thus be viewed as a window to the phenomenon of subjective response. In this era of hallucinogenic research, LSD was considered more of a “psychotomimetic” rather than a “psychedelic” drug. The former term implies that the drug experience “mimics psychosis,” whereas the latter denotes that the drug is “manifest in the mind.” Although in the introduction of his paper on LSD it was noted that the substance was associated with schizophrenia¬like symptoms, Beecher’s conclusion was that it likely expands or reflects the preexisting state of mind. This conclusion would later be echoed by Leary and others, who claimed that experiences under LSD reflect a subject’s “set” (ie, mind-set) and “setting” (ie, environment) rather than the mere pharmacology of the drug. To understand Beecher’s interest in concepts similar to set and setting, one must consider his experience in World War II. By doing so, intriguing questions arise as to the relationship between his psychedelic research and the US Government.

Beecher in World War and Cold War

Henry Beecher enthusiastically entered the conflict of World War II and served as a consultant in the beachhead campaigns of North Africa and Anzio, Italy. While in Anzio, Beecher noted that soldiers who were badly injured seemed to require far less morphine to relieve their pain than would a civilian with a comparable injury. He kept careful notes of his observations and would later hypothesize that pain had 2 aspects: the tissue injury itself and the meaning of the pain to the individual.6 The meaning of the pain dearly related to the environment in which the pain was experienced and the expectations and perceived consequences of that pain. Beecher published these observations after returning to the MGH and initiated a research program investigating the topic of pain and subjective response. Thus, his work on LSD and the evaluation of its effects was consistent with the broader context of his scientific inquiry of psychological meaning and drug response that originated in the war. Although it is certainly clear why Beecher might have been interested in LSD, it is a more fascinating question as to why the US Army was interested. Beecher’s work, as noted in the paper, was “supported in full by a grant from the Medical Research and Development Board of the United States Army.”3 It is likely that the Army was less concerned with the mysteries of the mind than the mysteries of mind control. Indeed, it has been reported that7: The intelligence agencies working through the US government financed drug research. An example is that Dr. Beecher of Harvard University was given via the US Army Surgeon General’s Office $ 150,000 to investigate “the development and application of drugs which will aid in the establishment of psychological control.”

It was common for investigators who were funded by such sources to publish some results in the medical literature and transmit other results directly to the government. It is thus unclear how extensive Beecher’s research on hallucinogens actually was. Beecher’s work on this topic may also have been funded or in some other way supported by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In a book on the history of LSD, Beecher is referred to as “an esteemed member of the Harvard Medical School faculty who conducted drug experiments for the CIA”.8 The CIA had a secret project exploring drugs for rnind control (a project called MKULTRA) and they were at the very least aware of Beecher’s research for the army. Beecher’s name appears in several files of the CIA and MKULTRA program that were obtained after declassification of the documents

Subproject 107: MKUL1RA: Amm-ican Psychwlogical Association: Army Jesting: Assassination: Raymond A. Bauer: Bmlin Poison Case: Biometr-ic Lab: Biophysical Measurements: Beecher (Henry K.): Brainwashing.

Beecher’s involvement in these programs was revealed decades after his death by his research associate Louis Lasagna during interviews with the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments in the 1990s. 10 As an investigator who was one of the early pioneers of ethics in human experimentation, it comes as little surprise that Beecher was reticent to discuss such work. It may appear paradoxical that Beecher both advocated the ethical treatment of human subjects and had also engaged in potentially unethical work on hallucinogens for the government. A more compelling hypothesis, however, is that Beecher advocated ethical treatment of human subjects largely because of such work.

—- The relationship of Beecher’s LSD research to his later contributions in bioethics is perhaps more interesting. Beecher had knowledge of Nazi experiments with mescaline in the concentration camp at DachauLinks to an external site. and was well aware of the potential for ethical abuse in the study of hallucinogenic substances. Although one might assume that his knowledge of Nazi experimentation with psychoactive drugs on unwitting subjects would have deterred any involvement in such research, it is important to note that Beecher was a vocal opponent of the application of the Nuremberg Code (crafted in response to such Nazi atrocities) to American medical experimentation. In one of his first important papers on bioethics in 1959, Beecher stressed the difficulty of applying the Nuremberg Code to clinical experimentation and brought into question the very concept of informed consent. In his classic 1966 publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, however, Beecher expressed a far more stringent view of ethical violations in medicine, a view that likely led to the implementation of Institutional Review Board protocols and informed consent (It is important to note that Beecher himself believed that ethical responsibility should rest with the investigator rather than the institution or its standardized regulations).

From LSD to the IRB Henry Beecher’s Psychedelic Research and the Foundation of Clinical EthicsGeorge A. Mashour, MD, PhD University of Michigan Medical School Ann Arbor, Michigan

***

Henry Knowles Beecher, an icon of human research ethics, and Timothy Francis Leary, a guru of the counterculture, are bound together in history by the synthetic hallucinogen lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Both were associated with Harvard University during a critical period in their careers and of drastic social change.To all appearances, the first was a paragon of the establishment and a constructive if complex hero, the second a rebel and a criminal, a rogue, and a scoundrel. Although there is no evidence they ever met, Beecher’s indirect struggle with Leary over control of the 20th century’s most celebrated psychedelic was at the very heart of his views about the legitimate, responsible investigator. That struggle also proves to be a revealing bellwether of the increasingly formalized scrutiny of human experiments that was then taking shape.

Jonathan D. Moreno, University of Pennsylvania, morenojd@mail.med.upenn.edu

Lyscrgic acid diethylamide (LSD) was brought to national attention by Dr. Timothy Leary. Leary was a well-respected psychologist on the faculty of Harvard University who developed an interest in hallucinogens after a personal experience with psilocybin in 1960 and ultimately developed this interest into both a scientific study and a cultural vision. Throughout the early 1960s, Leary and his colleagues – Dr. Ralph Metzner and Dr. Richard Alpert explored the effects of psychedelics at Harvard, resulting in both fame and infamy – especially for their studies on students. While Leary stands out as an early pioneer of psychedelic research at Harvard, it is rarely appreciated that Dr. Henry Knowles Beecher had published important work on the psychology of LSD some 10 years earlier. How is it that Beecher found his way to the study of LSD? The answer to this question is a fascinating history that spans from the shores of Italy in the 1940s to the frontiers of bioethics in the 1960s. It appears heretofore unrecognized that Beecher’s study of LSD in the 1950s may bear an important relationship to virtually all of his other endeavors.

George A. Mashour, MD, PhD University of Michigan Medical SchoolArm Arbor. Michigan

Study was done in 1956